A THUNDERING HART - The Hart Finley Story

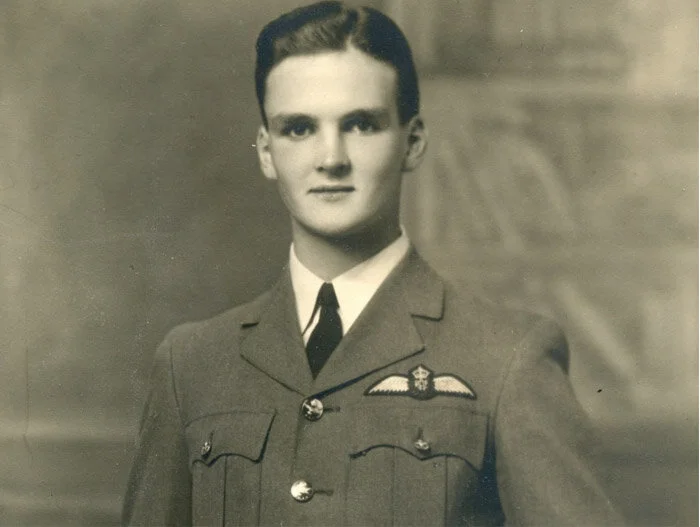

Hart Finley leans against the port wing of a 403 Squadron Spitfire. Inset: Hart Finley as a fledgling LAC in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940. Photos: Finley Family

During the Second World War, more than 72,000 young men served as pilots, navigators, air gunners, bomb aimers and flight engineers with the Royal Canadian Air Force, but following the end of hostilities, the vast majority never flew again. For Hartland Ross Finley, the end of the war was just the beginning of what would become one of Canada’s most distinguished flying careers. When he retired in 1965 at only 44 years of age, his career included being a Spitfire pilot with 6 1/2 kills, flying more than 50 different aircraft types (including a Messerschmitt Bf 108 and a Focke-Wulf Fw 190), and transporting many of the world leaders of the day as Canada’s first Chief VIP Pilot.

In early December of 1940, at only 19 years and with only 7 hours of actual flight training, Hart experienced his first solo flight in a Fleet Finch at No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School at Windsor Mills, Québec in the Eastern Townships. Several days later, while out flying, he realized that he wasn’t far from his alma mater, Bishop’s High School in Lennoxville, and so he decided to fly down and take a look. As he approached from the north and recognized the school quadrangle surrounded by buildings on three sides, he experienced a serendipitous flash that must have been characteristic of most successful fighter pilots when he calculated that he could drop down, touch his skis on the quadrangle and then gain enough altitude to make it up and over the last building. He successfully executed the manoeuvre and as he looked back over his shoulder, was rewarded to see many windows being flung open with students and teachers alike hanging out to see what all the racket was about. But as he continued back towards Québec City, his initial elation was replaced with increasing concern that his actions might be reported with the likely result that his flying days would be over. Through some miracle, no complaints were ever received and Hart vowed that he would never again take any actions that might unnecessarily risk his newly acquired love of flight.

Hart Finley (right) and fellow student pilots at No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School, Windsor Mills, Québec pose with Fleet Finch on the day of their first solos.

Pilot Blake Reid inspects the engine of the Vintage Wings of Canada Fleet Finch—RCAF Serial No. 4462. This Finch served at Windsor Mills at the time that Finley was there. A quick scan of Finley’s logbooks revealed that he had flown this very aircraft a number of times. This year, we will be dedicating the Finch in honour of Hart Finley. Photo: Peter Handley

The VW Fleet Finch has undergone extensive restoration this winter and will emerge shortly with new markings—those she wore when Hart Finley first flew her. Photo: Vanessa Lefaivre

Hart went on to train on Harvards at No. 9 Service Flying Training School at Summerside, Prince Edward Island. After receiving his wings, he trained as an instructor pilot with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and was promptly returned to the same Summerside facility where he earned his wings. Here he would instruct Australians, New Zealanders and Americans, as well as Canadians, to fly Harvards. In April 1942, he hoped that an urgent posting to RCAF Station Uplands in Ottawa would be a prelude to his journey overseas but it turned out that the RCAF was in need of his considerable football skills. After a very successful season training pilots by day at No. 2 Service Flying Training School, Uplands and playing football with the Ottawa Civil Service Rugby Football Union nights and weekends, his team, the Ottawa RCAF, lost the Eastern Canada final (13-18) to the Toronto RCAF Hurricanes who captured the Grey Cup the following week in Winnipeg.

A newly-winged and baby-faced pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, Finley’s first assignment, much to his consternation and frustration, was as a flying instructor at the same school he just got his wings at.

Related Stories

Click on image

During a second assignment as a flying instructor—this time at Ottawa’s No. 2 Service Flying Training School at Uplands—Hart Finley would play football for the Ottawa RCAF, a team that almost made it to the Grey Cup that year. They lost to the Toronto RCAF Hurricanes (seen here) who would go on to beat the Winnipeg RCAF at Varsity Stadium for the 30th Grey Cup in 1942. It is clear that the war had great impact on the makeup of football teams with all the eligible players joining the services.

Hart Finley at his Typhoon OTU standing in front of a Typhoon. Hart Finley was a big man, so one gets an idea of the massive stature of the big attack fighter. Many will think “If this was 1942, how come there are D-Day invasion stripes on this aircraft?” The early Typhoons had a set of stripes that were three black and two white. (An earlier use of black and white bands was on the Hawker Typhoon and early production Hawker Tempest Mark Vs. The aircraft had a similar profile to the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and the bands were added to aid identification in combat. The order was promulgated on 5 December 1942. At first they were applied by unit ground crews, but they were soon being painted on at the factory; four 12-inch-wide (300 mm) black stripes separated by three 24-inch (610 mm) white, underwing from the wing roots.)

A young Hart Finley (right) with some OTU pilots sitting atop the wing of a Typhoon in the summer of 1943.

Within another week he was checked out on Supermarine Spitfires and transferred to 416 Squadron under the command of Lloyd Chadburn operating with 11 Group out of RAF Merston, Sussex. On 12 August, exactly three years to the day that he walked into the recruitment office in Montréal, Hart flew his first operational sortie code-named Ramrod 196. After forming up with 3 other Spitfire squadrons to escort USAAF B-26 Marauder bombers to hit the airfield in Poix, France, they encountered extremely heavy flak. As the squadron approached the English Channel on the return flight, Finley was surprised to notice that his fuel reading was almost on empty. A wingman dropped underneath his plane and quickly discovered a fuel leak that could only have been caused by a flak burst. He was ordered to open the throttles to full power and gain as much altitude as possible but it wasn’t long before the engine quit entirely. After descending through the cloud cover to 2,000 ft he discovered that he was still only halfway across the Channel and completely surrounded by water.

Since he had always been concerned about getting clipped by the tail in trying to jump, he decided that he would ‘bunt’ his way out. This involved diving to gain airspeed, then pulling the stick back until the nose came up and over the horizon and then slamming the stick forward, thereby ejecting the pilot up and out of the aircraft (of course, he would have undone his seat straps by then).

Fortunately, it was still daylight and the seas were relatively calm, so he was able to inflate his dinghy and spend a few hours contemplating his first combat mission before being picked up by the Royal Navy and receiving some warm dry clothes together with the traditional shot of rum. He was taken back to base and flew his second mission two days later without incident.

In the second week of September 1943, Hart was posted to Johnnie Johnson’s 403 (Wolf) Squadron in Kent on the same day as the high scoring fighter ace, George (Buzz) Beurling. Beurling would teach Hart many of the tricks and tactics that had made him so successful in aerial combat in Malta, especially the art of “deflection” shooting. The squadron was equipped with Spitfire IXs which had a wing configuration allowing them to dogfight up to 30,000 ft, whereas the Spitfire Vs he had flown out of Merston had clipped wings and were used for lower-level bomber escorts. On 30 December 1943, Finley had his first aerial encounter with the enemy during a mission into France when he noticed aircraft far below his altitude of 20,000 ft, flying in the opposite direction. He was given permission to investigate with his wingman. The long descent increased their airspeed so much that by the time they were able to identify the aircraft as four Focke-Wulf 190s, they realized that they were going to overshoot the formation. The two Spitfires formed up line abreast and bracketed the 190s, with Hart on the left. Suddenly, the formation split and Finley turned into the pair breaking in his direction and was able to line up on the nearer of the two, blasting him from about 200 yards. The 190 straightened out, dropped its nose and headed for the ground while Hart gave it a final burst of cannon fire. The aircraft smoked noticeably, went out of control and impacted the ground. Hart’s wingman also scored a kill, but they always regretted not managing a more controlled descent, which they felt would have ensured four kills instead of two.

In September of 1943, 403 Squadron, including the newly-joined Hart Finley (right, in turtleneck sweater) inspect a Sherman tank.

During this period, the RCAF and RAF began experimenting with different tactics to meet their evolving combat roles. One of these tactics became variously known as a rodeo, rhubarb or roundabout and involved the use of only four to six aircraft performing low-level, search and destroy missions over occupied territory. In mid-1944, Hart was flying in one such rhubarb operation involving an airfield attack in France. As four of the six Spitfires approached just over treetop level, the ground fire became extremely intense. The Spitfire off Hart’s right wing vaporized in a ball of flame and the one on his left was hit badly. The pilot managed to fly past the airfield to crash land. (This pilot was picked up by the French resistance and eventually returned to Allied lines.) Hart continued in on the attack and succeeded in destroying a number of aircraft parked along the runway, but broke off and joined up with the other two Spits to fly cover for a third damaged aircraft on the way home. This pilot made it back over the Channel, but was forced to belly land at a coastal airfield, from which he was returned to Henley the following day.

A dashingly casual Hart Finley next to a 403 Wolf Squadron Spitfire in a rare nighttime photo. Compare the height of the Spitfire wing above ground to the photo of Hart with the Typhoon.

Shortly following this mission, Finley was ordered to Southend to train with a new gyroscopic gun sight and then following this, to instruct other 403 Squadron pilots in its use. This was the Mark II Gyro gun sight, which came into use at this time and was fitted mostly to the Spitfire XVIs. It was a marvellous piece of engineering that revolutionized aerial combat, eliminating the need for deflection shooting by allowing the pilot to simply put the gun sight on the target and squeeze the trigger. It became known as the “Ace” gun sight because it vastly improved the accuracy of aerial gunnery and gave the average fighter pilot a better chance to knock down enemy aircraft. The gyro sight remained the principal aiming technology in gun/cannon-equipped fighter aircraft until well into the 1970s.

After flying combat missions on a daily basis, month after month, activities became blurred, with few events standing out. One exception to this was an operation during which Hart’s squadron came upon ten Fw 190s flying, in what he described as an ‘odd’ formation. The Spitfires of 413 approached warily, wondering whether it was some sort of ambush. Finley dropped in right behind an Fw 190, so close he could “almost count the rivets”. His first concern was avoiding the debris that would undoubtedly fly off it when hit by the Spitfire’s machine guns, but when he pulled the trigger, nothing happened. After trying another two or three times, it was apparent his guns were hopelessly jammed. His squadron mates opened up and a fierce dogfight ensued, but Hart had no choice but to return to base.

In the spring of 1944, Hart Finley’s squadron was called to a briefing and given a very strange set of orders. Of the 30 pilots in 403 Squadron, 12 would now train to become ‘Hotspur’ glider pilots while the others would learn how to tow the gliders across the English Channel. Considerable time was spent on this exercise, but one day the gliders just disappeared and no-one ever knew why. The late Bill McRae at 401 was also so engaged. The plan was to take their servicing personnel to France in the gliders.

Army and Air Force pilots take instruction on the rudiments of flying the wooden Hotspur glider, which looked like a Mosquito without the engines. 403 and 401 Squadron pilots trained to fly or to tow these aircraft into the battle zone carrying their squadron maintenance personnel. Little can be found on the internet and in writing about this period, save what pilots like Finley and the late Bill McRae have written about. If anyone has an image of a Spitfire towing a Hotspur, we would love to see it.

A Hotspur pilot lifts off an airfield in England... perhaps towed by a Spitfire? Ground crew on their way to France would sit huddled in the narrow fuselage designed only for personnel transport. Thankfully, they didn't have to experience this “experiment”.

Another pre-invasion activity practiced by Hart’s squadron involved the use of 500 lb bombs in dive attacks on German flying bomb sites in France. Hart’s squadron was the first to use this ordnance and the pilots eventually developed their own tactics for attacking the sites. The attacks were successful in reducing the number of V-1s launched against London, but their effectiveness was questioned due to high losses experienced in the attacks. The launch sites were extremely well protected with flak guns and the Spitfires were always under intense shelling during their attacks.

In the late spring of 1944, Hart was in RAF Milfield on a Fighter Leaders course, when he received an urgent posting back to RAF Tangmere. As he circled the airstrip, he was perplexed to see that the markings on every aircraft had been changed to include black and white “invasion stripes”. He realized right then, that the long awaited D-day landings were eminent and as soon as he got out of his aircraft, he was advised that there would be a briefing at midnight.

In the briefing, they were told that the squadron would be providing air cover for American troops landing on Omaha and Utah beach. His diary describes the day of the invasion at Normandy as the most incredible sight of his life—with ships of every sort on the left and right as far as the eye could see. There was a continuous stream of fire arcing up and out from German shore batteries—matched by return fire from every ship carrying guns. As they flew over, they watched in amazement as two ships were hit by heavy artillery, broke in half and sank almost immediately.

To their shock and amazement, they realized that they too were under heavy fire from the ships below and Wing Commander Lloyd Chadburn, ordered them up and out of the combat zone to regroup while he called their base to find out “what the hell was going on”. They turned back toward France again but the friendly fire resumed—this time Chadburn’s Spitfire was hit, causing him to return to base. (Wing Commander Chadburn was killed in action over Normandy a few days later. He was 24 years of age. Canadian and British fighter pilots as well as American bomber crews openly wept at the news of the death of “The Angel”.) Finley assumed command of the 47 remaining Spitfires and tried a third time to enter the combat zone. This time, numerous squadron aircraft were hit, forcing them to return to RAF Tangmere. Hart attempted to enter the fray one more time, but again they took heavy fire and he was left with no choice but to order all aircraft back to base.

As the aircraft were refuelled, the pilots and base commander had a number of animated conversations with headquarters about how the situation should be handled. They were told that the ships had been properly informed of their arrival and so they should try again. This time, they were able to overfly the ships without incident and begin their task of strafing German positions and movements. They flew four missions that day, and fell into bed completely exhausted. 413 pilots were extremely surprised that, during the whole first day, they didn’t see one German aircraft fly over Omaha or Utah beach. They weren’t so lucky from the second day forward.

The next few days were also extremely busy and on 12 June, they were able to land in France at a temporary strip set up to refuel and rearm the aircraft. This made a tremendous difference in their attack capabilities, because it saved them the full hour to fly back and forth over the Channel. It was another week before their quarters were moved to France and the landing fields became less than temporary.

In Bomber Command, a tour of operations was set at 30 trips, but in Fighter Command, it was set at 200 hours. By the time Hart was called into the Wing Commander’s office and grounded he had logged 278 hrs. Pilots had the choice of quitting and returning home or remaining in non-combat operations for 6 months before they could resume fighting. Since Hart was keen to get back into the air war as soon as possible, he stayed on and was posted to RAF Balleyhalbert in Northern Ireland, where he instructed two Naval Air Squadrons in dive-bombing and strafing tactics on Supermarine Seafires.

Hart’s next assignment was with the experimental flight unit at RAF Boscombe Down, spending the next 3 months test flying the new Spitfire XXI. This was the most advanced Spitfire built—with a Rolls Royce Griffin engine and a completely redesigned wing which eliminated forever the classical elliptical shape so widely recognized as synonymous with the Spitfire. The new wing configuration also involved replacing all of the machine guns with four 20mm cannons. A 5-bladed 11-ft diameter propeller was added to carry the additional weight and some variants even included a six-bladed counter-rotating propeller which greatly improved handling characteristics.

A Spitfire XXI similar to those test-flown by Hart Finley during his non-combat tour.

One day, while out flying, he found himself close to Bournemouth, and since his job as test pilot was to push the aircraft to the limits of its performance, he decided to do a ‘wave top’ high-speed flyby similar to what he had seen on his first day there in 1943. The flyby went well and he followed it up with near vertical climb to 21,000 ft, when there was a loud “bang”, followed by complete engine failure and flames coming from the starboard side of the engine. He sideslipped the plane away from the flames, while he radioed in his situation and wondered whether he would have to bail out. By the time he descended to 17,000 ft the flames had died out and he decided to attempt to glide the airplane in. Because it was an experimental and test base, Boscombe Down had a very long runway, but Finley was uncertain about whether his hydraulics would operate to lower the gear. Given the high risk of sparks and fire if he had to belly land, he decided to use the grass adjacent to the runway. As it turned out he was able to lower the landing gear and to execute a perfect landing.

Just before Christmas 1944, he was given leave to return to Montréal, and following a wonderful Christmas with his family, he returned in March 1945 to begin his second tour with 403 Squadron. The unit was now based in Petit-Brogel, a recently constructed frontline base in Belgium, in the outskirts of Brussels. In a matter of weeks, they moved forward through Eindhoven, Holland; Goch, Germany, Diepholz and finally Soltau, southwest of Hamburg.

On 24 April, Hart was transferred to 443 Squadron (also based at Petit-Brogel) as a flight commander. It was there that he added two to his aircraft destroyed total.

A pair of Spitfires of No. 443 Squadron, 127 Wing RCAF, beat up the airfield over the squadron’s flying control unit at Petit-Brogel, Belgium, March 1945. Photo via the fabulous spitfiresite.com website

Hart’s last combat operation took place on 2 May, when his new unit received intelligence about a German airfield near Lembeck where there were still quite a few operational fighters based. Hart ‘laid on’ a mission to attack this field and at 2:00 P.M. in the afternoon, 6 Spitfires under his command took off. They made two attacks on the airport, inflicting heavy damage on parked aircraft.

As they turned to leave, low on fuel, he spotted a twin-engine Ju 88 aircraft at about 4,000 ft. Calling the spot to his squadron mates, he pulled into a climb to investigate. At just about the time the Spits were ready to open fire, the German airplane rolled into a near vertical dive—coming so close to the deck that Hart began to have an uneasy feeling that the pilot wouldn’t be able to pull up in time. The Ju 88 pulled hard out of the dive with no more than fifty feet to spare and had built up so much airspeed that vapour trails were streaming off both wingtips. As the German airplane hedgehopped over trees and buildings Hart began hitting it with bursts from his .50 calibre Browning machine guns and could clearly see pieces breaking off from the strikes. In time, the German airplane stopped weaving, lost speed and began gliding towards the ground. Hart immediately pulled up, but, as he passed over the Junkers, it hit the ground and exploded into a massive fireball. Debris from the explosion hit Hart’s Spitfire and his cockpit immediately filled with flames.

There was no time to think about what he should do, it was escape or die and so he held the stick back with his legs to gain more altitude, unbuckled his harness, removed his helmet and slid back the canopy. His speed had declined to about 115 mph and he attempted the same ‘bunting’ technique to escape the cockpit as he had used over the Channel, but as he was thrown up, his right flying boot became jammed between the seat and the fuselage.

Hart was buffeted around in the slipstream, partially out of the Spitfire with the open canopy jamming him in the back, his foot firmly caught, and flames engulfing him. All he remembered thinking was “My God I cannot die this way” as he kicked and screamed with every ounce of adrenaline in his body pumping for a solution. He broke free, pulled the rip cord on his parachute and the second it blossomed, he hit the ground, landing in the middle of a small field. Through some miracle, he hadn’t suffered any serious physical damage (though he did have burns and scrapes), but was experiencing some degree of shock as he stood up to gather his senses and his chute. At this point, he heard voices shouting, whistles blowing and dogs barking. He saw a large group of people running across the field towards him. Rifle shots rang out as he ran up a hill toward a copse of wood, where he thought he might gain some cover. Attempting to run, he realized for the first time that his flying boot was still in the Spitfire.

He would recall the ‘zinging’ sound of bullets as they passed him, while others thudded into the ground around him. He succeeded in making it over the brow of the hill and into the woods without getting hit. He ran in what he believed was the general direction of the front line until he found a small depression in the ground. He buried himself with leaves and worked to quiet the deafening sound of his thundering heart. One German pursuer came so close, that Hart could feel the fall of each footstep. By this time, darkness had set in and the leaf camouflage worked.

After another hour or so he got up, wrapped his scarf around his right foot and worked his way in a south-westerly direction. The next day, he made contact with a British tank crew who gave him something to eat and helped him make it to a field hospital at Lauenburg where his minor wounds and burns were dressed and he was able to eat some food and find a new pair of boots. He was informed that medical staff had made arrangements for his evacuation to England the next day and then he was left alone to catch up on some sleep. Finley had no intention of missing any more of the war, and so, when staff were occupied with other patients, he got dressed, ducked out, and commandeered a jeep to take him to the nearest aerodrome—near Luneburg about twenty kilometres away. He radioed his base and arrangements were made to have the Wing’s Auster fly over and return him to base at 6:00 P.M. on 4 May. The next morning as they sat down to breakfast, the end of hostilities was announced.

Hart elected to stay with the Army of Occupation and on 31 May 1945, while his squadron was posted to Soltau, Germany he received a visit from W/C J.F. (Stocky) Edwards who had commandeered an Fw 190. The two exchanged aircraft to assess the relative merits in a dog fight and both were convinced that the Spitfire XVI was the superior aircraft in a combat role. About this time, Hart also flew a Messerschmitt Me 108 and a communications aircraft called a Blucher 181.

Prior to a test flight, we see Hart Finley at the controls of an RCAF marked Focke-Wulf Fw 90 at Soltau, Germany at the end of the war. The aircraft bears the JFE markings of James Francis “Stocky” Edwards who was visiting Finley at the time. The size of the German fighter is evident here, being considerably larger than the Spitfire Hart usually flew. Having flown against the type many times in combat, Finley relished the opportunity to understand what he had been up against. Both pilots felt that the Spitfire was superior.

On 8 June, he was promoted to Squadron Leader in command of 443 Hornet Squadron and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for skill, courage and determination with a combat score of 6 1/2 enemy aircraft destroyed. By this time, the squadron was housed in a former Luftwaffe base at Uterson that provided all of the comforts and amenities such as RAF Tangmere. By the time Hart requested permission to return to McGill in September 1945, his total flying time on Harvards over 1 1/2 year of training pilots in Canada was in excess of 1,000 hours and on Spitfires (including time on Royal Navy Seafires), he had logged 582 hours. Of this total, 385 hours were on “operations” (2 tours), accumulated during 224 separate missions.

Studying for a commerce degree at McGill felt mundane compared to flying combat missions over Europe and so Hart tried to distract himself by playing football. However, when KLM Royal Dutch Airlines announced that it was recruiting 60 pilots in Canada, he couldn’t resist going for an interview and was hired on the spot.

For the next year and a half, he served as a Captain with KLM flying DC-3s and DC-4s on national and European routes, while living in Amsterdam not far from Schiphol airport. He enjoyed the Dutch people and became fairly fluent in their language. In 1948, while on holidays in Ottawa, a friend persuaded him to be interviewed by a review board of the Department of Transport, which was in the process of establishing a V.I.P. service to fly the Prime Minister, Members of Cabinet and visiting dignitaries. The review panel was suitably impressed and offered him the top post as Chief Executive Pilot and Head of Service. This was an auspicious trip home for Hart because he also met a young woman named Marg, whom he married one year later.

For the next seventeen years, as Captain of the Canadian Government’s flagship Viscounts and Lockheed JetStars, Hart flew a list of world dignitaries that covers three pages, single spaced. This included every Canadian Prime Minister, five different British Prime Ministers and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip. Hart also had the distinction of being the only non-American to ever fly a President of the United States. This was in September of 1964 when he flew Prime Minister Lester Pearson and President Lyndon Johnson from Great Falls, Montana to Vancouver for implementation of the Columbia River Treaty.

Hart Finley (left) stands with other crew members from the Royal Tour of 1959 in front of the grey and gold Department of Transport Vickers Viscount CF-GXK.

Finley accumulated many hours on the beautiful Vickers Viscount CF-GXK of Canada’s VIP flight, seen here in August of 1972 at Ottawa International Airport. Photo: Steve Williams

While Finley retired after a life of service to his country, he contributed to his community and remained a vibrant character until the end of his days. Not so, his beautiful Department of Transport Viscount, which became the efficient-sounding Transport Canada Viscount with a much less elegant paint scheme. It languished at Ottawa airport for a while before being stripped, cut up, used and burned as a fire training fuselage in the early 1980s. Photo: David Bland

Finley greets Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker prior to boarding the Department of Transport VIP Vickers Viscount.

A career, which started on the little yellow Fleet Finches of Windsor Mills, ended with the Lockheed JetStar, the muscle car of business jets. Photo: Howard Chaloner

Family responsibilities finally intervened, and in 1965, Hart resigned as Chief Executive Pilot and joined the Civil Aviation Division. In 1970, he became Head of the newly formed Aviation Safety Division. When the ASD merged with the Accident Investigation Division, Finley was named as its first Director. He was awarded the Canadian Centennial Medal in 1967 for his many years of accident free transport service for the Canadian Government.

Hart retired from Canadian Government service in 1977, and continued his contribution to society by participating in a wide range of community services including the Boy Scouts of Canada. In 2005, Hart and Marg moved to Vancouver for health reasons and his last project involved working with the group responsible for the Roseland Y-2K Spitfire project. Hart passed into history on 22 January 2009, ending a long and most distinguished life.