THE SUN OR THE MOON OR THE STARS

“We scarcely saw the sun, or the moon, or the stars. For hours we saw none of them. The fog was very dense, and at times we had to descend to within 300 feet of the sea.” — 23-year old Sir Arthur Whitten Brown

This past weekend marked 100 years since the Atlantic Ocean was crossed non-stop from one side to the other for the first time. That 16-hour flight, flown by John Alcock and Arthur Brown, two First World War pilots and recent prisoners of war, was just 16 years after Orville Wright's first 120-foot, 12-second powered flight. In 1919, the science of powered flight had come an astonishingly long way in a very short period of time, but it was still a very crude science with underpowered aircraft made of wood and fabric and held together by wires. Yet, it had come to a point where two young adventurers would stake their lives on its dependability in an attempt to cross an immense ocean at night with no support whatsoever.

There are those of us, the ones with over-active imaginations, who can sense the vastness and empty black, cold depths of the North Atlantic 40,000 feet below us when we fly to Europe on a Boeing Dreamliner. As we sip our Cabernet Sauvignon in Business Class, the hairs on the backs of our necks rise if we contemplate the chances of survival if the unthinkable happened. Best to ask for another glass and get back into that Jack Reacher novel.

Imagine the courage it took to lift a creaking, two-ton fabric and wood behemoth, powered by just two 360 hp engines, from a rough farmer's field and then deliberately head out over the ocean towards its other shore, nearly 2,000 miles away. Despite knowing very little about the weather they would encounter, having primitive instruments and running into serious trouble about one third the way (their radio and intercom ceased functioning six hours into the flight), they risked it all for the chance to be first, for the adventure, for the accomplishment and for the prize money.

Alcock and Brown will forever be mentioned together as if they were one person, but they had just met prior to the attempt. Their accomplishment was indeed extraordinary, only eclipsed by their courage—the kind of courage found in people like Amelia Earhart, Yuri Gagarin, Neil Armstrong, and Felix Baumgartner; the kind of courage that is paired with an extraordinary trust in an untried technology.

I won't go into the whole story of their harrowing flight which hung on the edge of disaster almost the entire time, but offer up Wikipedia's synopsis of the event, followed by a portfolio of photographs that tell their story at either end of the flight. There is evidence that both men had cameras with them in Newfoundland, but there are no known photographs taken during the flight.

“Several teams had entered the competition and, when Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland, the Handley Page team were in the final stages of testing their aircraft for the flight, but their leader, Admiral Mark Kerr, was determined not to take off until the plane was in perfect condition. The Vickers team quickly assembled their plane and, at around 1:45 p.m. on 14 June, whilst the Handley Page team were conducting yet another test, the Vickers plane took off from Lester's Field. Alcock and Brown flew the modified Vickers Vimy, powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle 360 hp engines which were supported by an on-site Rolls-Royce team led by engineer Eric Platford. The pair brought toy cat mascots with them for the flight – Alcock had 'Lucky Jim' while Brown had 'Twinkletoes'.

It was not an easy flight. The overloaded aircraft had difficulty taking off the rough field and only barely missed the tops of the trees. At 17:20 the wind-driven electrical generator failed, depriving them of radio contact, their intercom and heating. An exhaust pipe burst shortly afterwards, causing a frightening noise which made conversation impossible without the failed intercom.

At 5.00 p.m., they had to fly through thick fog. This was serious because it prevented Brown from being able to navigate using his sextant. Blind flying in fog or cloud should only be undertaken with gyroscopic instruments, which they did not have. Alcock twice lost control of the aircraft and nearly hit the sea after a spiral dive. He also had to deal with a broken trim control that made the plane become very nose-heavy as fuel was consumed.

At 12:15 a.m., Brown got a glimpse of the stars and could use his sextant, and found that they were on course. Their electric heating suits had failed, making them very cold in the open cockpit.

Then at 3:00am they flew into a large snowstorm. They were drenched by rain, their instruments iced up, and the plane was in danger of icing and becoming unflyable. The carburettors also iced up; it has been said that Brown had to climb out onto the wings to clear the engines, although he made no mention of that.

They made landfall in County Galway, crash-landing at 8:40 a.m. on 15 June 1919, not far from their intended landing place, after less than sixteen hours' flying time. The aircraft was damaged upon arrival because of an attempt to land on what appeared from the air to be a suitable green field, but which turned out to be Derrygimlagh Bog, near Clifden in County Galway in Ireland, although neither of the airmen was hurt. Brown said that if the weather had been good they could have pressed on to London.

Their altitude varied between sea level and 12,000 ft (3,700 m). They took off with 865 imperial gallons (3,900 L) of fuel. They had spent around fourteen-and-a-half hours over the North Atlantic crossing the coast at 4:28 p.m., having flown 1,890 miles (3,040 km) in 15 hours 57 minutes at an average speed of 115 mph (185 km/h; 100 knots). Their first interview was given to Tom 'Cork' Kenny of The Connacht Tribune.

Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes on the completion of their flight. In addition to a share of the Daily Mail award of £10,000, Alcock received 2,000 guineas (£2,100) from the State Express Cigarette Company and £1,000 from Laurence R Philipps for being the first Briton to fly the Atlantic Ocean. Both men were knighted a few days later by King George V.

Alcock and Brown flew to Manchester on 17 July 1919, where they were given a civic reception by the Lord Mayor and Corporation, and awards to mark their achievement.

For an outstanding and colourful recounting of the various attempts at the crossing and Alcock and Brown's harrowing and ultimately successful crossing, I highly recommend this story by Graham Wallace in Macleans magazine from September, 1955, just 36 years after the event.

Captain Sir John William Alcock, KBE, DSC, a 27-year old former flying instructor, fighter pilot with the Royal Naval Air Service and Turkish Prisoner of War during the First World War, was born in Stretford, England in 1892. Following the war, he was employed as a factory pilot with Vickers, where he took up the challenge to attempt the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

Lieutenant John Alcock (front and centre) was a pilot with the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

Alcock had a one-off aircraft type design to his name—the Alcock Scout, (called the Sopwith “Mouse” by Alcock), was a curious experimental fighter biplane flown briefly during First World War. It was assembled by Flight Lieutenant John Alcock at Moudros, a Royal Naval Air Service base in the Aegean Sea. Alcock took the forward fuselage and lower wings of a Sopwith Triplane, the upper wings of a Sopwith Pup and the tailplane and elevators of a Sopwith Camel, and married them to a rear fuselage and vertical tail surface of original design. It was powered by a 110 hp Clerget 9Z engine, and carried a .303 Vickers machine gun. Alcock never got to fly his creation as he was shot down and captured on a bombing raid over Turkey on the 30th of September 1917 and his scout took flight for the first time on October 15th. It was flown most often on offensive patrols by Alcock’s squadron-mate Flight Sub-Lieutenant Norman Starbuck. In early 1918, the Scout was written off in a crash and never rebuilt. Photos: Imperial War Museum

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Arthur Whitten Brown, KBE, 23-years, was born in Glasgow in 1896 to American parents. During the First World War, he first served as an infantry officer at the front before joining the Royal Flying Corps' 2 Squadron. He too was shot down (twice) and spent some time as a prisoner of war, interned in Switzerland. After the war, Brown, an engineer, came to the attention of Vickers and was asked to partner with pilot Alcock as the flight's navigator. Photo: Margaret Carter

The Vickers Vimy aircraft used in the crossing was a repurposed heavy bomber developed during the last year of the First World War. Vimy bombers did not play a part in the war, but would soldier on with the Royal Air Force until 1933. The Vimy used by Alcock and Brown was transported aboard the steamship S.S. Glendevon to St. John's, Newfoundland in wooden crates, then brought from the docks onward by horse-drawn cart to a landing field at Quidi Vidi, where competitors Raynham and Morgan had just recently crashed their Martinsyde Raymor (a one-off aircraft which got its name by combining the first letters of Raynham the pilot and Morgan the navifgator) during their attempt. Judging by the dimensions of this crate, it contains the fuselage assembly.

Local muscle, including excited children, move the massive cart and crate containing the four wings. The crates first arrived at Quidi Vidi Lake on May 26, 1919. The field was too short to attempt to take off in a fully loaded Vimy.

The Vimy is assembled at Quidi Vidi. Vickers and Rolls-Royce mechanics travelled across the Atlantic aboard the same ship that brought the crated Vimy and were helped by local tradesmen.

Mechanics and helpers built two large wooden trestles to hoist the wings into place and hold them while riggers set the bracing wires and struts.

Fuel or oil is pumped by hand into tanks aboard the Vimy. The Vimy carried a total of 865 Imperial gallons of petrol (3,900 litres) and 40 gallons of oil at take-off. Note the large funnel in the foreground.

Curious St. John'sers lounge on the grass at Lester's Field as final preparations are made in the days leading up to the attempt. This photo was possibly taken shortly after or before the previous shot as the fuel barrel and funnel are in the same spots.

A great shot of the ground crew—the aircraft riggers and mechanics from Vickers and Rolls-Royce who helped get the big aircraft ready

Alcock (left) and Brown pose with the Vimy during its final assembly at Quidi Vidi Lake. Each appears to be carrying a box camera. One wonders if they took photos during their flight, though none came to light in my searches of the internet.

Alcock (left) and Brown discuss details with an engineer from Rolls-Royce or Vickers as the aircraft nears completion. Photo: Newfoundlandlabrador.com

On the same occasion in the days leading up to the flight, Alcock (cigarette in hand) poses for a publicity shot and hands a bag of St. John's, Newfoundland Post Office mail up to Brown in the cockpit.

Propellers appear to be turning in this shot—it's not known whether this is just prior to the take-off or if this was an earlier engine test before the flight from Quidi Vidi Lake over to Lester's Field.

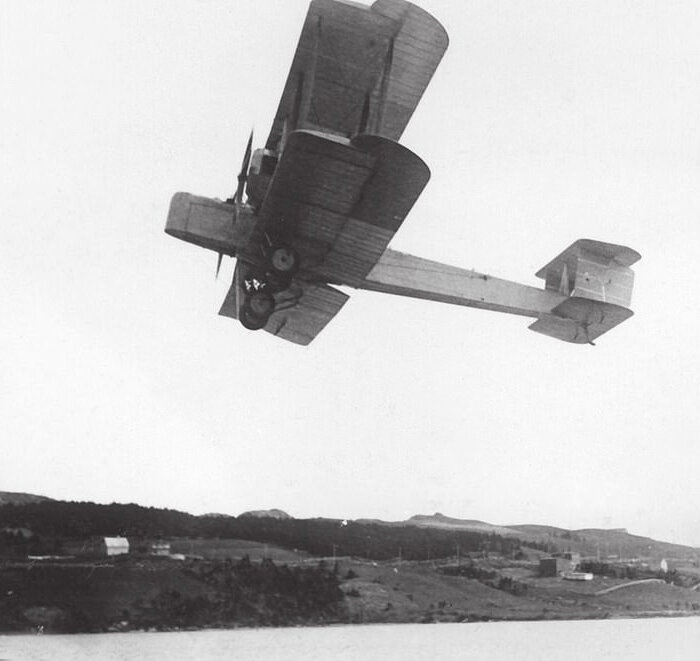

This view with Alcock and Brown climbing out is often used to represent the actual attempt, but the landscape looks more like Quidi Vidi Lake than Lester's Field.

With Alcock at the controls and Brown navigating, the Vickers Vimy lifts off. Once again, this appears to be the small field at Quidi Vidi Lake where the Vimy was assembled. In this shot, we see the clear evidence that the nose skid was not installed for this flight—perhaps to reduce drag.

Children and adults alike throng view the Vickers Vimy and rub shoulders with history. Since the aircraft was assembled at Quidi Vidi Lake, then flown to Lester's Field for the attempt at the crossing, it's difficult to assess at which field many of these photos were taken.

Children and adults alike throng view the Vickers Vimy and rub shoulders with history. Since the aircraft was assembled at Quidi Vidi Lake, then flown to Lester's Field for the attempt at the crossing, it's difficult to assess at which field many of these photos were taken.

Alcock relaxes on a barrel of oil or petrol prior to the flight. Photo: Margaret Carter

Alcock (right) and Brown relax and picnic on a grassy slope overlooking the inner harbour at Lester's Field on the day of their attempt. Photo: Margaret Carter

Dignitaries or friends join Brown (left) and Alcock (facing) before their flight.

The Vimy awaits take off —possibly at Lester's Field as the people sitting on the ground (in silhouette) at lower right could be the picnickers from the previous photos.

A thermos of something hot is handed up to Alcock (lower photo) as they begin final preparations for the flight. Most Vickers Vimy aircraft were equipped with a nose skid to prevent the nose from striking the ground (upper photo), but the airframe that Alcock and Brown used did not have this feature. Had it been installed on this Vimy, it's possible that they would not have ended up on their nose as they eventually did.

With its starboard engine warming up, Alcock is assisted with something by a member of the ground crew standing on a saw horse. Note the translucent wing fabric which reveals the ribs inside. Photo: Margaret Carter

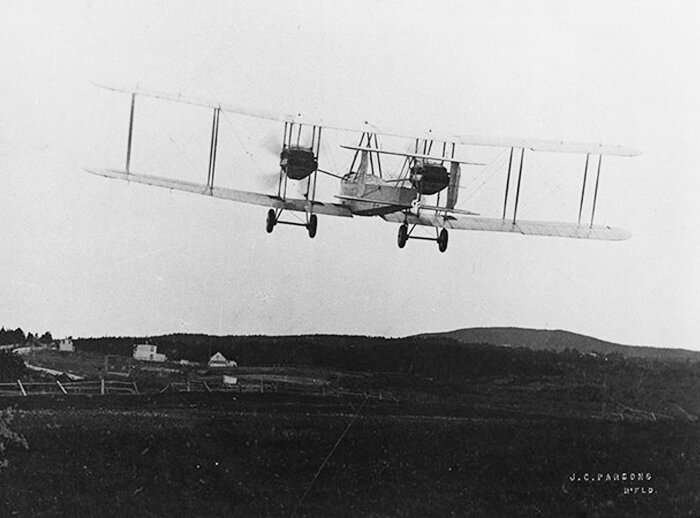

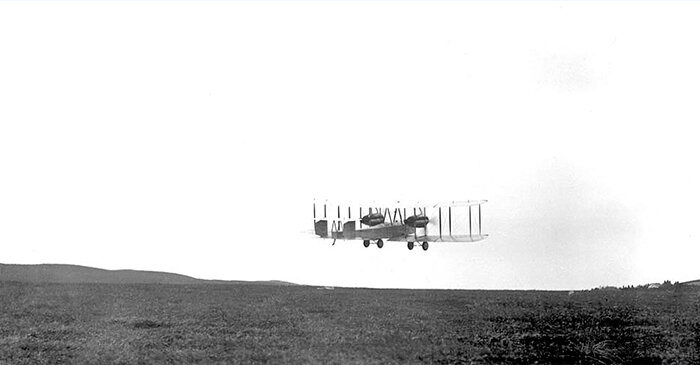

Alcock and Brown climb out of Lester's Field near St. John's, Newfoundland at 1345 local time, bound for Great Britain where they made a rough landing 16 hours later.

Another view of the Vickers Vimy lifting off from Lester's Field

After a harrowing 16 hours in bad weather, Alcock and Brown nosed over after touching down on Derrygimlagh Bog in County Galway near the town of Clifden. Had the Vimy's standard nose skid been in place, perhaps the outcome would have been better. Here British Army guards stand watch to prevent souvenir hunters from vandalizing the wreck.

Locals around Derrygimlagh and Clifden come to stare at the wreck—for many the first glimpse at an aircraft up close. With the steady winds blowing in off the North Atlantic, the wings and tail of the Vimy had to be tied down to prevent more damage to the now-historic aircraft.

Guards are placed at the wreck of the Vimy. Brown and Alcock would most certainly been ejected had it not been for the fact that they were wearing safety belts.

John Alcock and Arthur Brown, likely at the wreck site (there appears to be upturned wings in the background) following their historic flight.

The two aviators came down in a Galway bog very close to a Marconi radio station. Because of the boggy land, the station was supplied by its very own narrow gauge railway upon which this strange little rail car was operated. The car was used to bring the two aviators out of the bog.

Today, all that remains of the Marconi radio station are the foundations in the foreground. The bullet-like white memorial in the distance marks the exact spot where Brown and Alcock came down 100 years ago. Image via Google Maps

Alcock and Brown (in uniform) pose with the bag of mail which they carried aboard the flight. The small amount of mail that was carried aboard made this also the first transatlantic air mail flight. Perhaps the bag of mail was small because of the great risk that it would not make it. Alcock holds a model of some sort of biplane... but not one of a Vickers Vimy.

Put on display in Ireland after their ordeal, Brown (left) and Alcock look tired and a little embarrassed. Alcock holds the model airplane from the previous photo and with them are their two good luck mascots. Alcock is holding “Lucky Jim” while Brown's “Twinkletoes” sits on the St. John's, Newfoundland mail bag. Twinkletoes was donated to the RAF museum at Cosford, Shropshire. To celebrate the 60th anniversary of their flight, the RAF flew Twinkletoes back to Newfoundland in a McDonnell F-4 Phantom II. This time the trip took just 6 hours and the landing was uneventful.

Purple headlines in the Montreal Gazette the following day proclaimed that the “Atlantic is shrinking.”

The New York Times reported that “they looped the loop unintentionally at times”. Image via New York Times

Judging by the damage to the aircraft in the background, this image was taken after the recovery of the Vimy.

The recently knighted Sir John Alcock (second from left, front row) and Sir Arthur Whitten Brown (third from right) pose with executives of the Humber Limited after their successful flight. Photo via thehistorypress.co.uk

Like Lindbergh eight years later, Alcock and Brown benefited from their fame with endorsements—here the two aviators ride in a new Humber motor car (note same building as previous photo). The caption reads: “A FAMOUS AIRMAN AND HIS CAR. SIR JOHN ALCOCK MOTORING. This 10 h.p. four-seater Humber car is the property of Captain Sir John Alcock, KBE, DSC, the pilot of the airplane which flew the Atlantic. He is seen at the wheel, and next to him is Captain Sir Arthur Whitten Brown, KBE, who was his navigator in the great flight. The photograph was taken outside the offices of the Humber Works, at Coventry.”

Then Secretary-of-State for War Winston Churchill presents John Alcock and Arthur Brown with the promised £10,000 prize money (approximately £145,000 or $245,000 today) from the Daily Mail during a dinner in their honour. Churchill said: “I do not know what we should admire the most—their audacity, their determination, their skill, their science, their Vickers Vimy airplane, their Rolls-Royce engines or their good fortune.”

Alcock and Brown pose with their repaired Vickers Vimy at an aviation event at Brooklands, in August, 1919. In many of Brown's photos, he is carrying a walking stick. This was not an affectation but rather a necessity as he suffered permanent and painful leg injuries when he was shot down the second time during the First World War. Photo: Public.Resource.org via flickr.com

On 18 December 1919, just days after he and Brown were in attendance at a dedication of their aircraft to the London Science Museum, Alcock was piloting a new Vickers Viking amphibious flying boat to the first post-war aeronautical exhibition in Paris when he crashed in fog at Cottévrard, near Rouen in Normandy. Alcock suffered a fractured skull and never regained consciousness after being transferred to a hospital in Rouen. Photo: Imperial War Museum

For anyone wanting the full story of Alcock's and Brown's harrowing and improbable flight across the Atlantic, I highly recommend Brendan Lynch's Yesterday We Were in America, the most definitive and most recent of all the books on that doughty pair of aviation pioneers.