LUCKY LINDY AND UNLUCKY THAD

The Lone Eagle and the Twelve Hawks

After his historic crossing to Paris and two short flights—to Belgium and then London, England—Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis were carried back to Washington D.C. aboard the light cruiser, USS Memphis. Here, to enormous fanfare and pride, Lindbergh was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by President Coolidge and promoted to Colonel in the US Army reserves. The Ryan NYP Monoplane was reassembled and then flown by Lindbergh to Roosevelt Field on Long Island, the same airfield from which he began his solo crossing. In New York, he was given a tickertape parade down Broadway. From New York, he flew the Spirit of St. Louis back to his home in St. Louis, to thank his financial supporters at the St. Louis Raquette Club. From there he began a three-month publicity tour of America... but first, he came to Canada.

On Saturday, 2 July 1927, a little more than six weeks after his world-astounding solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, Charles Lindbergh was, without a doubt, the most famous and most revered man on the planet. Lindbergh was the toast of every town in America. City officials and wealthy people across the United States of America were vying for his attention and presence. Yet here he was flying the Spirit of St. Louis, in the company of twelve new Curtiss P-1 Hawk biplane fighters and three Royal Canadian Air Force aircraft, over Canada’s Parliament Buildings along the banks of the Ottawa River. Below, the entire city of Ottawa watched as he swept overhead. Sixty thousand citizens waited his arrival at Ottawa’s Hunt Club Field and along his motorcade route into town.

Lindbergh had been invited to Ottawa, the capital of young Canada to help celebrate its Diamond Jubilee. The day before, in an excited spasm of national pride, thousands of Canadians had crowded Parliament Hill to celebrate their country’s 60th birthday. The festivities on this 60th Canada Day included the inauguration of the newly completed Peace Tower, the centrepiece of today’s Parliament Buildings, as well as the laying of a cornerstone for the Confederation Building, the fourth edifice of the Parliament Buildings precinct. While they were sharing their newfound Canadian spirit, 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh lifted off the runway at Lambert Field, Missouri, outside of St. Louis and flew more than five hours (via Fort Wayne, Indiana and Toledo, Ohio) to Selfridge Field, a US Army Air Corps base near his hometown of Detroit, Michigan. After landing at Selfridge, he allowed the base commander, a Major Lanphier, to take the Ryan NYP (for New York to Paris) for a short local flight, then spent the night in the company of fellow US Army fliers. Then on the morning of 2 July, he took off for Ottawa, the capital of Canada, and the first stop on a three-month-long public relations tour across America. On his four hour and ten minute flight direct to Ottawa, he was accompanied by no less than twelve Curtiss P-1 Hawk biplane fighter aircraft of the 27th Squadron of the First Pursuit Group.

The scene on Parliament Hill on the 60th Canada Day/Diamond Jubilee weekend of 1927. It is not certain if this photo by Hy Gould was taken on 1 July or the following day when Lindbergh had arrived. In this scene, we see all the military trappings and dignitaries necessary to greet a hero like Lindbergh, or in the case of one of his escort pilots, put together a state funeral. Photo: Hy Gould, part of the Hyman and Lilian Gould Family fonds, Ottawa Jewish Archive

Colonel Charles Augustus Lindbergh, The Lone Eagle, the most popular and revered man in the world, flies his Ryan NYP Monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, over Parliament Hill on 2 July 1927, just weeks after his triumph over the Atlantic. Photo: Hy Gould, part of the Hyman and Lilian Gould Family fonds, Ottawa Jewish Archive

Twelve Curtiss P-1 Hawk fighter aircraft of the 27th Squadron of the First Pursuit Group of the US Army Air Corps accompanied Lindbergh along with three Rockcliffe-based RCAF aircraft. Here the Yanks are seen arriving over Ottawa in four Vee formations, led by a Major Lanphier. There could be a number of reasons that the 27th had this incredible honour. Lindbergh himself was born in Detroit, Michigan, and the 27th trained for its part in World War One in Canada – Likely at Borden, Ontario. The squadron's commander in those training days was Harold E. Harteny – a Canadian. Today, the unit, known as the 27th Fighter Squadron, USAF, is the oldest active fighter squadron in the United States Air Force, flying the F-22 Raptor from Langley AFB, Virginia. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

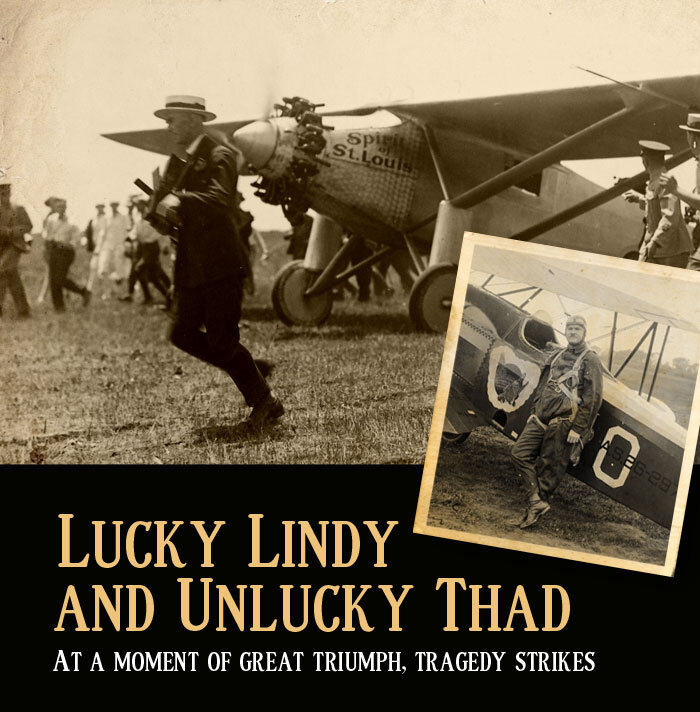

Lieutenant John Thaddeus Johnson, of the 27th Pursuit Squadron, was piloting a Curtiss P-1 Hawk, the latest in US Army fighter aircraft. The type was in service with the US Army from 1924 to 1929, with a total of 202 being built in a number of variants. It was the first US aircraft to be given the “P” for Pursuit designation. Photo via Wikipedia

Proceeding northeast, they flew past the Ontario cities of Windsor, London and Toronto and then angled northeast toward Ottawa. They were met over the capital city by three aircraft of the recently formed Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). After circling the newly completed Peace Tower, and turning south, the flying entourage swept over the centre of the city, picking up the Rideau River and the Bowesville Road. Below, nearly every citizen of the city watched as they passed overhead. As they approached the Ottawa Hunt Club’s new golf course south of the city, they could see the two crossing grass landing strips south of the intersection of Bowesville and River Road. Here, they could easily see that thousands of Ottawans had come out to greet them.

Lindbergh was the first to land, rolling down the runway to great excitement and jubilation. Attending members of the RCAF and the press ran alongside the Spirit of St. Louis as it rolled out following landing and began taxiing to the southeastern end of the shorter runway. The slower he taxied the more people rushed in to greet him.

Crowds of spectators and hundreds of cars await Lindberg’s arrival along Hunt Club and Bowesville Roads.

The Spirit of St. Louis trundles along after touching down at Ottawa’s Hunt Club Field. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Gunning his Wright Whirlwind radial engine and raising dust, Lindbergh is surrounded by running men eager to help the great conqueror of the Atlantic Ocean. Photo via Canada Aviation and space Museum

A press photographer in a straw boater hat scrambles to stay ahead of the taxiing Spirit of St. Louis as members of the RCAF and others reach out to touch the most famous aircraft in the world and help guide its pilot. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

After landing at Ottawa’s Uplands, Charles Lindbergh taxies his Ryan Monoplane past the first of thousands of onlookers. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Following Lindbergh, the escorting US Army aircraft began to land. As one of the last groups of three P-1 Hawks prepared to land, the pilot of one of the aircraft was seen to dip as if to come into land, but then quickly rise to resume his position in the formation. It was thought that perhaps he had encountered turbulence from another aircraft. The fighter’s tail made contact with the propeller of another Hawk in the formation and his empennage was shredded. The aircraft, no longer in the control of its pilot, pitched down towards the ground. The pilot could be seen immediately climbing out of the cockpit and attempting to parachute to safety. Unfortunately, being only a few hundred feet in the air, the man’s parachute did not have time to fully deploy and both man and machine impacted the ground as horrified spectators looked on.

The man was 32 year old, Texas-born Lieutenant John Thaddeus Johnson, a former Christian preacher, and a highly experienced fighter pilot, having flown during the First World War. What happened next at Hunt Club Field is explained in a story in the Spokane Spokesman-Review of the following day:

“Colonel Lindbergh had entered an automobile and was being whisked away to where Canadian officials were waiting to welcome him. Mounted police surrounded his car, and Lindbergh first heard the news from a sergeant riding at his side. Only a few words of greeting had been exchanged [between] the reception committee members and Colonel Lindbergh when he broke in: ‘You will have to excuse me—I want to go and see about the boy [Lindbergh was actually 7 years younger than Johnson] who crashed.’

He climbed into an open roadster [a Franklin boat-tailed Sport Runabout] and was taken across the field and over the brow of the hill where the scout plane lay a wreck. Lieutenant Johnson’s body had been placed in an ambulance, and mounted police and military units held back the crowds. Major Lanphier, U.S.A. [the Selfridge Field Commander] and Group Captain Scott, Royal Canadian Air Force, joined Colonel Lindbergh in asking questions of witnesses and arranging for a formal investigation.

Stern, Coatless and Hatless

Then Lindbergh went back to carry out his part of the program, but there was no “Lindy smile.” He sat in the car with stern face, coatless and hatless, with goggles pushed back on his forehead, while the crowds, who had not learned of the tragedy, cheered wildly in welcome.

After freshening up at the Ottawa Hunt Club, the transatlantic flyer was taken to Parliament Hill for a reception and then to Government House [Rideau Hall] for a luncheon with the Governor General and Lady Willingdon. The Canadian government took charge of Lieutenant Johnson’s body. Premier Mackenzie King, deeply touched by the accident, immediately dispatched a message to President Coolidge expressing sympathy of the Canadian government and people to the government and people of the United States.

The government also took steps to get in touch with the flyer’s widow, Mrs. Edith Johnson, at Selfridge Field. A guard of honour, composed of members of the Royal Canadian Air Force, probably will be placed over the body until it is sent back to the United States.”

The last sentence would prove to be one of the greatest understatements of the period, for the Prime Minister and the Canadian government, perhaps to dress the emotional wounds they could clearly see on Lindbergh’s face, lapsed into an outpouring (bordering on a paroxysm) of grief, emotion and over-the-top ceremony that included a state funeral at Parliament, and a massive funeral procession attended by thousands of politicians, dignitaries, military servicemen of all stripes and thousands of local citizens.

Newspaper reports from the days afterwards state that Johnson’s wife Fay had collapsed at her parents’ home on hearing the news, while his father suffered a heart attack when he was told.

Charles Lindbergh’s appearance that afternoon on Parliament Hill and at Rideau Hall still pales in comparison to the pageantry, ceremony and drama of the state funeral conducted the very next day for a man no one had ever heard of. Perhaps it was a way of impressing Lindbergh and leaving him with a favourable impression of Ottawa and Canada. Perhaps it was to demonstrate to an attentive planet, who was following the Lone Eagle’s every move, that Canadians were an honourable people. Perhaps it was genuine grief, but one look at the funeral events that took place the very next day and the amount of organization that happened overnight and one wonders if it was all for Johnson or for Lindbergh.

The scene of Lindbergh’s arrival as photographed after Lindy’s Spirit of St. Louis shutdown. The location is where today we would find the North Field at Ottawa International Airport and the Ottawa Flying Club. To the left is the Rideau River. The road which angles from lower right to mid-upper right was called the Bowesville Road in those days and ran through the site of today’s modern Ottawa airport. The dark cluster of trees at right centre is the Ottawa Hunt Club and we can just make out its new 18-hole golf course which was built just three years previously. We can also make out thousands of Ottawans who have come out to catch a glimpse of the world’s most famous human being—lining the Bowesville Road and the River Road which runs to the lower left. Lined up on the eastern end of the shorter runway we can see the lighter colour of Lindbergh’s Ryan Monoplane as well as the remaining eleven US Army scout planes which had accompanied him. If one looks even closer, at the very bottom of this photo, we can see a cluster of gawkers surrounding Thad Johnson’s crashed aircraft. Also, given the mass of automobiles found at the intersection of Bowesville and River Roads, it is likely that this is Lindbergh’s motorcade leaving for downtown Ottawa. Photo: Ottawa Archives

Zooming in even closer to the scene at Uplands, we see a crowd gathered around Thad Johnson’s crashed aircraft, showing us the power of a tragic event over the draw of the most famous man in the world. Photo: Ottawa Archives

The twisted wreckage of Johnson’s Curtiss P-1 Hawk sits forlornly in a field next to the runways prepared for Lindbergh’s arrival. Photo via André Audette

Looking more like 15 than his 25 years, Lindbergh looks decidedly concerned as he sits in the cockpit of his Ryan Monoplane. It is not known if he had yet been told of the mishap involving Lieutenant Thad Johnson, but the look on his face, which should have been one of delight, lends credence to the possibility that he is now aware of the death. Newspapers reported that he was informed of the accident after he had climbed into a car. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

After shutting down and climbing out of the Ryan Monoplane, Charles Lindbergh allows himself to pose for the cameras. In the background stands Walter Deisher, who would chauffeur him in a Franklin Sport Runabout car for the drive into Ottawa along the Bowesville Road. Lindbergh should have been smiling for this photo, but it is likely he has just been told of Johnson’s death, minutes before. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Charles Lindbergh, still wearing his flying goggles, is escorted across the grassy infield of the landing area near the Ottawa Hunt Club to the spot where Thad Johnson had crashed. Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Army officers surround him as he is whisked away in a Franklin Sport Runabout driven by Mr. Walter Deisher, who was not only an enthusiastic proponent of aviation, but also a Reo car dealer in Ottawa. The car was described in the local papers as light grey in colour. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

A formal US Army portrait of Lieutenant John Thaddeus “Thad” Johnson. Johnson was born in Texas in 1895. His early plan for a career was to be a minister and a preacher. He was educated at Trinity College in Waxahachie, Texas. When the First World War finally drew the Americans into the fight in April of 1917, Johnson volunteered, doing his initial army training at Leon Springs, Texas. After commissioning in May of 1917, he was sent for flying instruction at Rockwell Field (now known as NAS North Island in San Diego). He made it over to France while the war was still going on, but it seems he did not see combat. After the war, as a member of the US Army Air Corps, he participated in the first transcontinental flight (from New York to San Francisco) in 1919. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

Lieutenant John Thaddeus Johnson with a Curtiss P-1 Hawk, likely taken at Selfridge Field, Detroit. The eagle symbol of the 27th Pursuit Squadron (Nicknamed The Fighting Eagles) is still in use today, with the squadron in continuous operation for almost 100 years. Johnson died when his parachute failed to open in time, but two years previously, he survived a 10,000 foot jump from a P-1 Hawk at Eagles Mere, PA when his fuel line caught fire. Lindbergh himself had survived 4 parachute jumps prior to Johnson’s death—two as an Army Air Corps pilot and two as a US Mail pilot. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

One of the other US Army Air Corps pilots who accompanied Lindbergh poses with his Curtiss P-1 Hawk at the Hunt Club Airfield. All 12 aircraft were from Selfridge Field in Detroit, Michigan. This particular Hawk is not from the 27th, but rather ther 17th Pursuit Squadron of the same First Pursuit Group. It is possible that 17 Squadorn pilots were part of the flying entourage, or possibly the aircraft was “borrowed”. This particular pilot appears to be somewhat unconcerned or perhaps unaware of Johnson’s demise. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

As soldiers and airmen move in close for a better look at the Ryan Monoplane known as the Spirit of St. Louis, two young Ottawa ladies pose with the famous ship that crossed the Atlantic. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

A corporal of the recently formed Royal Canadian Air Force stands guard over the Spirit of St. Louis. The RCAF had just been formed from the nascent Canadian Air Force three years previously. There are several photographs in this collection from the Canada Aviation and Space Museum that were clearly taken by a photographer whose camera shutter had some defect that caused the tear-like black shape at right. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

A sombre-looking Lindbergh and Walter Deisher ride in the Franklin car arranged for the motorcade. Though he seems to be averting the adulation, he is mobbed by youths on bicycles and adoring fans. This photograph can easily be placed on the Bowesville Road, half a kilometre north of the Ottawa Hunt Club’s pine tree copse. After landing at Uplands, Lindbergh went to the Ottawa Hunt Club to change and freshen up, which explains the difference in clothing from earlier photos. Police on motorcycles were having a difficult time keeping the crowd in check. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

A clearly disturbed and brooding Lindbergh on his way to downtown Ottawa. His driver, Walter Deisher, an American-born business man, is one of the most important early figures in Canadian aviation.

Lindbergh and his driver Walter N. Deisher ride into town in silence. Deisher’s 1956 obituary in Toronto’s Globe and Mail reads: “Walter Nice Deisher, 65, former vice-president and general manager of Avro Canada, Ltd., died in his Thornhill home, yesterday after a lengthy illness. Mr. Deisher, an aviation pioneer, remained director and advisor of the aircraft company after his retirement in 1951. He was Avro’s general manager from 1945 when the firm was formed, until 1951. Born in Shenandoah, Va., he was educated as an automotive engineer in Shenandoah and in Cleveland where he worked for the White Motor Co. In 1912 he came to Toronto to handle sales and services for the company. His experience in aviation goes back to the early days of flying. He became a pilot in 1912 and held a license signed by Orville Wright. In 1919, he bought a Curtiss Jenny and barnstormed throughout Eastern Canada. In 1929, he was elected chairman of the first national convention of flying clubs at Ottawa. In 1930, he joined the Fleet Aircraft Co., where he was vice-president and general manager from 1943 until he moved to Avro. He founded Laurentian Air Services Ltd., and purchased a section of land just outside Ottawa for flight operations [this is actually on the same spot as Lindbergh landed–Ed]. Mr. Deisher was a director of Leyland Motors Canada Ltd., a member of the Society of Automotive Engineers since 1917, and a member of the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences. He was a member of the Ottawa Flying Club and the Empire and Canadian Clubs of Toronto”. Photo: Bill Mains Collection

Lindbergh, looking far less happy than he should be, is squired through adoring crowds on Parliament Hill by American Ambassador William Phillips. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

From a dais on the lawn of Parliament Hill, Lindbergh addresses the crowd of Ottawans out to see the world’s greatest hero. It is likely that few on the Hill that afternoon were aware of the tragedy which had taken place earlier south of town. To the right of Lindbergh we see Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who would remain as Canada’s Prime Minister for more than 20 more years. The three microphones carried live the messages of dignitaries across the breadth of Canada in a bilingual broadcast of speeches, songs, poems and peals of the carillon bells in the newly inaugurated Peace Tower, the likes of which had never before been heard. Click here for a recorded radio broadcast on Canada Day, the day before Lindbergh’s appearance. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

One can read a couple of important things in this image of Lindbergh addressing the crowd on Parliament Hill in downtown Ottawa. The first thing that strikes you is his undeniable youth. At the time, Lindbergh was just 25 years old. Secondly, we can sense that he is haunted by the realization of Johnson’s death and that the joy that was meant for this occasion of celebration has vanished. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Following Lindbergh’s appearance on Parliament Hill, he was driven the two kilometres to Rideau Hall, the residence of the Governor General of Canada, for a reception in his honour. There was no shortage of people hoping to get their photograph taken with Lindbergh. Here, at Rideau Hall, he stands with the Honourable Vincent Massey (right) and William Phillips. Massey, a decorated veteran of the First World War, would become Canada’s first native-born Governor General. In 1927, Massey was known as the Canadian Envoy Extraordinaire and Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States for his Majesty’s Government in Canada (now called the Canadian Ambassador to the US) and William Phillips was the first American Minister to Canada (now known as the American Ambassador to Canada). Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

A respectful Lindbergh shakes the hand of Governor General Lord Willingdon at Rideau Hall, the historic residence of the Vice-Regal. At far left is Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King with William Phillips. Behind Lindbergh, Vincent Massey smiles broadly. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

On the Saturday evening, as Lindbergh dined with Canadian dignitaries, the wheels of government sped up to takeoff speed and by the very next day, what appears to be one of the grandest funerals ever to take place in Ottawa, before or since, was organized—honour guards, bands, police, floral arrangements, black arm bands, rifle platoons, sailors, airmen, gun carriage, horses, a flag-draped coffin, thousands of invited dignitaries and a private funeral train to bring the body home immediately. Of course, the guest list included any dignitary already in town for the Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

As the funeral procession moved down Wellington Street to Union Station, Lindbergh was nowhere in sight. It is possible that many of the thousands in attendance were there to catch a glimpse of the Lone Eagle, especially in his hour of grief. But he was not to be seen. The coffin containing Thad Johnson’s body was draped in an American flag and borne to the station and the awaiting funeral train on a gun carriage driven by scarlet uniformed Mounties. The pallbearers were all pilots and airmen of the Royal Canadian Air Force and they carried his coffin to the black-draped funeral train through the train shed entrance on MacKenzie Street. As the coffin was carried into the dark shadows of the great station, members of the Governor General’s Foot Guards Band played the Star Spangled Banner and The Last Post. Guardsmen, resplendent in scarlet tunics, brass buttons, black bearskin “busby” hats, lifted their white strapped rifles to the sky and fired volley after volley splitting the silence of the moment, the reports making spectators jump, horses skitter and pigeons rise in terrified flocks over the station.

But where was Lindbergh? People had to be asking.

As the locomotive drew the funeral train from the depths of the train shed and began its slow procession out of the heart of the city, it followed the eastern bank of the Rideau Canal, where, at the first bend in the canal, it would curve to the east to pick up the mainline going west and south. As the train creaked and black smoke and white steam rose from the loco, several aircraft appeared out of the low clouds to the south—the Spirit of St. Louis escorted by seven of the Hawk fighters of the 27th Pursuit Squadron. As the Hawk fighters circled, the Ryan NYP descended towards the city centre, following the last bend in the canal and turning towards the slow moving train, passed low overhead, while Lindbergh tossed flowers from his tiny window. As people watched from various vantage points, the Spirit of St. Louis made repeated passes over the slow moving funeral train, with Lindy dropping flowers at every pass (it was reported that they were peonies and photographs of the flowers on the train confirm this). Train crews picked up all the flowers they could and laid them on Johnson’s casket.

There could be no more dramatic send-off for a flyer than to have the greatest of them all pay tribute in this poetic and heartfelt fashion. The logbook for the Spirit of St. Louis shows that the flight over the funeral train lasted one hour and ten minutes. The next entry in the logbook indicates that he left Ottawa on Monday, the 4th of July, bound for Teterboro Airfield, New Jersey. The weekend’s events had been deeply tragic and sorrowful and were reported all around the world. They had affected the citizens of Ottawa and Lindbergh deeply, but today, they are largely forgotten. The only things to remind people that these events happened are two street signs on the airport property. But very few today ever stop to think or ask why there is a street named Thad Johnson Private.

Dave O’Malley

Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow would return to Ottawa four years later, flying their famous Lockheed Sirius 8 on floats, landing this time on the Ottawa River at RCAF Station Rockcliffe. Again, Ottawa was the first stop—this time on the Lindberghs’ great circle route mapping expedition that took them from North Haven, Maine to Canada, Alaska, Russia, Japan, and China.

Escorted by black arm-banded members of the new Royal Canadian Air Force, the gun carriage bearing Johnson’s body rolls slowly down the east driveway of Parliament Hill after he had lain in state in the Centre Block. To the left in the background stands the newly completed Peace Tower (inaugurated 1 July 1927), from which the Belgian Master Carillonneur Lefèvre, punched out Chopin’s “Marche Funèbre” dirge, as the procession moved down Wellington Street towards Union Station. It appears that the pallbearers all have RCAF pilot’s wings and plenty of “gongs” from the First World War. Photo: Ottawa Archives

A black-draped truck carrying the floral tributes to Thad Johnson follows the gun carriage from Parliament Hill. The funeral truck carries the letters R.C.A.S.C.L.L.548—which stands for Royal Canadian Army Service Corps Light Lorrie 548. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

An artillery gun carriage bearing the flag-draped coffin of Lieutenant Thaddeus Johnson makes its way down Wellington Street in Ottawa. In the background stands the grand Victorian facade of Ottawa’s Central Post office, which stood where, today, we find the National War Memorial. Its facade is decorated with bunting and the numerals 1867–1927 in celebration of the 60th birthday of a young nation. The state funeral has drawn many dignitaries who were likely in Ottawa for the birthday celebrations on Parliament Hill. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Thad Johnson’s funeral cortege drew thousands of mourners and spectators. This photograph is likely taken from the roof of the entrance of the Chateau Laurier Hotel. It shows members of the funeral procession walking behind the casket as it turns right toward the side entrance to Union Station. The front entrance to the station is just to the right and out of view in this photograph. Nearly all the buildings in this photograph have long since vanished, including the Chicago-style Daly Building at left, which housed Lindsay’s Department Store. The only building visible in this shot that is still standing is the taller structure in the background, which sits today at the southeast corner of Rideau Street and Colonel By Drive. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

At the side entrance to Ottawa’s Union Station, Johnson’s casket, draped in the Stars and Stripes, is lifted into the great hall by pallbearers of the newly formed RCAF. Mounties on horseback draw the gun carriage away, while busby-wearing members of the Governor General’s Foot Guards Band play a sorrowful tune. The scene is flanked by dignitaries, soldiers and sailors, while the curious watch from station windows. The truck bearing floral arrangements follows the entourage. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Red-coated Guardsmen fire their rifles in salute to Thad Johnson as his casket is carried away by the train. Sadly, the buildings in the background were all raised decades later to make room for the Rideau Centre shopping mall. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Later (possibly after the funeral) with the Ryan tied down and suitable stanchions and ropes in place, two guards allow three spectators to pose for a photograph with the world’s most famous aircraft. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Spectators at the soon-to-be-named Lindbergh Field at Uplands stand somewhat quietly to view the Spirit of St. Louis as Lindbergh runs up the Whirlwind. Given the cloudy conditions, the subdued crowd and the larger aircraft behind Lindbergh’s Ryan, I believe that this photograph and the next were taken as he departed Ottawa. I studied this larger aircraft for quite some time trying to identify its type. Thanks to Tim Dubé for suggesting it was likely a Douglas O-2 observation aircraft. The aircraft would have come after Lindbergh had left for Parliament Hill and likely belonged to the US Army, in Ottawa after the crash to help the investigation. Perhaps one of the oddest features of the airfield was the 60-foot-tall pine tree at the edge of the shorter of the two runways (approximately in the same direction as today’s Runway 32). Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Charles Lindbergh taxies the Spirit of St. Louis along the line of eleven Curtiss P-1 fighters of the United States Army. I believe, given the direction he is travelling and the lack of accompanying runners or large crowds, that this is a photo of his departure—either to drop flowers over Johnson’s funeral train on 3 July or his ultimate departure to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. On this final flight, Lindbergh circled overhead Ottawa for 35 minutes. We can see men discreetly waving to Lindbergh as he taxies by—possibly the pilots of the Curtiss P-1 Hawks. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

More about Thad Johnson

Despite several glaring typos, the local Fenton, Michigan newspaper paid tribute to their hometown hero, Thaddeus Johnson. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

Emotional headlines clipped from the Ottawa Morning Journal. Though well-deserved, it’s hard to believe that they would have been so large and dramatic if Johnson had not been escorting the most famous man in the world at the time of his demise. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

It appears that Johnson had more than one aerial mishap, something common to all pilots in the early years of flight. Here, he and his wife Fay Adams Johnson smirk as they pose with a flipped P-1 Hawk. Johnson was also forced to jump from his burning aircraft in Pennsylvania, just two years prior to the Ottawa accident. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

Johnson (right) was involved in lengthy winter testing of the Curtiss P-1 Hawk fighter in the 1920s at Selfridge Field near Detroit. The Wikipedia entry for the 27th Pursuit Squadron states: “Under extreme and austere conditions in the 1920s they tested the effects of cold weather on their aircraft. At times it was so cold, the engines of their P-1 Hawk aircraft would not start until steam was forced into the engines to thaw them.” Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

Thaddeus Johnson, likely during winter trials of the P-1 Hawk in the 1920s. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

Lieutenant Thaddeus Johnson, commanding officer of the 27th Pursuit Squadron in better days. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum, Thaddeus Johnson Special Collection

The Franklin Car

A Franklin Sport Runabout car similar to the one which carried Lindbergh to the soon-to-be-cancelled celebrations on Parliament Hill. Photo by A. Wittenborn

In 1928, the H.H. Franklin Company of Syracuse, New York presented Lindbergh with a luxury sedan, which they christened the “Airman”. Though Lindbergh had been bestowed many gifts, the Franklin was a favourite. He later wrote: “The Franklin car was a present from the Franklin Company because, they said, my flights in the “Spirit of St. Louis”, with its air-cooled engine, had increased the sales of the car – the only car built in the United States with an air-cooled engine... I drove this car a great deal in connection with my flying activities... I drove my wife in it on the first date we had—to Long Island for a flight in a de Havilland Moth—and on a good many dates thereafter, both before and after we were married. I like the car very much and it gave us excellent service.” In 1940, Lindbergh donated the car to the Henry Ford Museum. Photo and text from Henry’s Attic: Some Fascinating Gifts to Henry Ford and His Museum, by Ford R. Bryan

Because Franklin cars featured an air-cooled engine, Franklin advertisements of the late 1920s strove to make a connection with the exciting and revered world of aviation. Images via the internet

All that remains to remind people of the dramatic events that happened 88 years ago are two street names at the Ottawa International Airport. Thad Johnson’s street was downgraded from Drive to Private a few years back. People come and go all day, but very, very few know the source of the street’s name and the tragedy that it memorializes. Photo: Dave O’Malley

At the other side of the airport from Thad Johnson Private is another short street, commemorating the visit of Lindbergh. The street is not much further than 100 metres from the place he parked his aircraft after landing at Hunt Club Airfield. Photo: Dave O’Malley