NIMROD, THE MIGHTY HUNTER

Arguably the most beautiful biplanes ever built [By the British - Ed.] and the most famous aircraft serving with Commonwealth forces between the wars were the classic silver Hawker biplanes. The “family” of biplanes started in 1928 with the first flight of the Hawker Hart which was destined to be the new day bomber for the RAF. The Hart’s aesthetic lines were due to the new Rolls Royce Kestrel liquid-cooled V-12 engine. The Hart’s introduction into the RAF had created a situation where a day bomber was faster than fighters in service at the time. Its success led to the development of new types and derivatives based on this exceptional design.

The “family” included the Audax which was designed as an army co-operation aircraft and the need for a Hart-type for the Royal Navy led to the Osprey. The Hawker Hind was developed to replace the Hart. The next inevitable stage was to develop a single-seat fighter. This led to the Hawker Fury, the first aircraft in RAF service to exceed 200mph. Although the Fury looked generally similar to the Hart it was smaller than its two-seat relatives, having a different primary structure and not using the same major components. All of the family of Kestrel-engined Hawker aircraft operated throughout the British Commonwealth as well as with a number of European air forces such as Denmark and Spain.

In 1934 a group of Hawker Furies visited Toronto Flying Club and the Rockcliffe airfield in Ottawa. While they were in Toronto, observers from the US Army Air Corps carried out a detailed analysis of the aeroplanes. Their report stated;

“the British Ships gain speed through the use of geared liquid cooled motors, which allow very clean fuselage design compared to our ships, using the large fuselage cross sectional area required with retractable landing gear...

“Above all, the power contained at altitude through improved supercharging is responsible for the high velocities obtained with what seemed to be comparatively dirty aeroplanes aerodynamically...

“Much of their remarkable climb performance is due to the superior supercharging, in addition they climb by keeping the gross weight down, through the use of wooden propellers, cross axle type landing gear, single lift wires, smaller quantities of fuel and oil because of the superior fuel economy of their engines...

All those who have seen the very rare surviving examples of the Hawker biplanes in the air have remarked about how distinctively beautiful they are. Whilst they have striking looks, their sound is striking too. At 21 litres, the Rolls Royce Kestrel is only 6 litres smaller than the Merlin and sounds quite similar to it. It is strange to hear the thunder one expects from a Spitfire only to see a sleek biplane, so different from anything else in the historic aviation and air display world today.

Louis Geoffrion chats up three members of the Canadian Forces Parachute Demonstration Team, The SkyHawks Though Louis has only jumped from an airplane once, it was one jump that had the respect of troopers with hundreds and even thousands of jumps for it was into the Mediterranean Sea after being shot down while on ops during the Second World War. Photo: Peter Handley

Related Stories

Click on image

The new generation of airworthy Hawker biplanes; Nimrod I and II, soon to be joined by the Fury, would not be flying today without the massive efforts of Guy Black and Retrotec, formerly Aero Vintage. Guy has resurrected many of the Hawker engineering techniques that have disappeared over the years. When he first became involved with Hawker biplane types, the world’s only flying example was the Shuttleworth Collection’s ex-Afghanistan Air Force Hawker Hind.

The most significant of the engineering problems resolved by Aero Vintage related to the wing spars. Without the wing spars there was no means by which to properly restore the complete aeroplane. In the 1980s a Fury replica originally owned by the Honourable Patrick Lindsay was constructed. However, it was not possible to manufacture spars and these ended up being made from wood.

The Hawker biplane uses a complex dumb-bell shape steel spar, conceived by Roland Henry Chapman in 1926, and later patented by Sidney Camm for Hawkers in 1929. This spar is made up of two flanged, polygonal booms, folded from high tensile steel strip, riveted to an inter-connected flange. To manufacture such spars today necessitated obtaining special steel from a company with a large strip rolling mill to create steel in coiled strip form. Guy had to go to Switzerland to find such steel. The strip rolling mill is a 60 foot long cast iron table with a number of powered stations turning shaped rollers. Each of these pairs of rollers is different, and various pairs are necessary to form any one section.

The solving of the spar manufacturing problem gave life to a new generation of Hawker aeroplanes - not only the biplanes but also a new generation of Hawker Hurricanes, including the Vintage Wings of Canada Mk.IV. Additionally, the Hawker biplanes and the Hurricane fuselage rely on tubes squared at the ends. They are assembled in a complex way using stainless steel joining plates with up to 80 separate items per complex joint. The tube squaring machine at Retrotec was re-created from photographs of the original Hawker machine - reverse engineering in the truest sense.

“Finding skilled people with a knowledge of pre-war engineering practices was very difficult. In the main we have had to train them from scratch. The spars were an enormous problem but we solved it Engineering problems are a great challenge but finding skilled people is the most difficult” said Guy Black

It is Guy’s belief that the Hawker biplane design is the result of the aeroplanes requirement to serve throughout the British Commonwealth. As Royal Air Force and Royal Navy resources were spread far and wide, the repair of a welded fuselage type structure would not be possible in the field in many Commonwealth countries. However, as the Hawkers were a cluster of tubes held together by stainless steel plates, spacers, bolts and tubed rivets, and if spares were held, they could be fitted in place and welding was not required. With no welded joints, there can be no movement between parts - hence the use of so many components to stabilize and strengthen each joint. However, the complex manufacture enabled simple maintenance in the field or onboard ship.

Vintage Wings of Canada’s founder Mike Potter with Retrotec’s Guy Black looking at the latest projects - a Hawker Fury and DH9. “It was a great opportunity to meet Guy and see what a wonderful job Retrotec is doing to bring some very historic aircraft back to life” said Potter. Photo Howard Cook

Hawker Nimrod II – Royal Navy Fighter

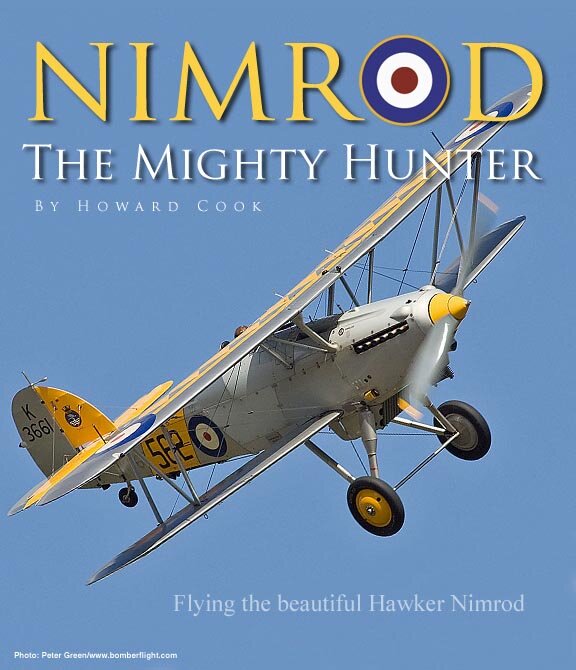

To the casual observer the Hawker biplanes “all look the same”. The Nimrod came to be because the Royal Navy required a single seat biplane fighter, as did the RAF with its Fury. Although the Nimrod looks similar to the Fury, the former has maritime additions such as flotation bags, hoisting gear, spare detachable wings, arrester gear and a strengthened fuselage to withstand the stress of catapult launches. The Nimrod II has a swept back top wing, enlarged tail and a 600hp Kestrel Mk.V . With a maximum take off weight of 4,050lbs, it is about 500lbs heavier than the Fury and has a wingspan 3ft greater than the RAF fighter.

The Nimrod II I would fly (K3661, manufacturer serial 41H.59890), was completed on 5th September, 1934. On 1st January, 1935 it was placed in storage at Cardington and then on 7th October, 1936 went to the packing depot at RAF Sealand. It was issued to 802 Flight in the Mediterranean on 23rd October 1936 with the side code number 562 and it served from 1936 to June, 1938 when it suffered two landing accidents. It was placed on Admiralty charge on 23rd May, 1939 and then sent to Lee on Solent in December, 1939.

A Royal Navy officer in dress uniform runs alongside Hawker Nimrod II K3661 as it makes a very sketchy landing aboard HMS Glorious in 1938. Most likely this is a rare photo capturing one of two landing accidents that ended the service life of this beautiful aircraft. Photo: Fleet Air Arm Archive

In 1972 the Nimrod was discovered on a rubbish dump in Ashford, Kent, more or less complete but well corroded. It was recovered and donated to the RAF Museum which stored it at RAF Henlow. After Henlow’s closure, the fuselage was sold off to Mike Cookman from whom Guy Black acquired it in August, 1991.

Investigating the aeroplane’s past, Mike Llewellyn, the proprietor of the Battle of Britain Museum at RAF Hawkinge, telephoned Guy with the news of a display case full of parts from the Nimrod, including control column, instrument panel, map box, ammunition chutes, and many other items, including the original cockpit data plates, confirming the serial number as K3661. It is believed the aircraft may have ended its service as an airfield decoy.

The restoration of the K3661 commenced in 1992. British Aerospace was helpful in the early days of the project but it is unfortunate that full sets of drawings were destroyed by students working for them some years back. The discovery of a large number of drawings in Denmark enabled the restoration to progress further and K3661, now registered G-BURZ, made its first post-restoration flight in November, 2006.

Much valuable data had been gained from the development and testing of the first Hawker Nimrod I (S1581), the first of Retrotec’s Hawkers to complete its restoration which took eight years. 1581 made its first post-restoration flight in July of 2000 and paved the way as the first of the Retrotec “production line”. It was operated by Duxford-based Historic Aircraft Collection for two years and went through a test schedule very similar to the program that it would have flown in the 1930s. It was handed over to the Fighter Collection in September, 2002 in exchange for Hurricane Mk.XII G-HURI.

Flying the Nimrod II

First Impressions

Just looking at the aeroplane as you walk out to it generates thoughts of the RAF Hendon Air Days of the 1930s. One is immediately struck by its sheer beauty from any angle and it makes one feel as if one should be dressed in all-whites to fly it. With the benefit of his great experience in testing and flying the Hawker Nimrod 1 and II, pilot Charlie Brown gave me his usual very thorough conversion-to-type brief. He then told me to go off and sample the ways of the early Hawkers and in this instance the world’s only surviving Hawker Nimrod II. It looks the predecessor to the Hurricane from every angle, sans the upper wing.

The imposing size of the Nimrod is very evident here as Cook, himself over six feet chats with ground crew from the Historic Aircraft Collection at Duxford, England. It’s not every day one does this sort of thing in 2008, so best stop to experience the moment and take in all the information these experienced and dedicated men can offer. Photo Randall Haskin.

It is quite a climb getting into the aeroplane which feels a bit like going up by the North-West route! You must be particularly careful not to put your feet through the beautiful fabric work. Sitting in the cockpit for the first time feels like looking out of a tank hatch, although with plenty of room inside. It is not just the outside view of the aeroplane that sets the mind back to the halcyon days of flight. The cockpit, with its dials, brass fittings and Vickers S gun breeches is equally evocative.

The Hawker Nimrod II control panel - with British-type spade-handle control column and two wooden handles for arming the Lewis guns. Photo Howard Cook

Ready to Start

The Nimrod normally requires two groundcrew to prepare it for flight and assist with the start. A Spitfire takes three hands to start, the Nimrod can take four! It has three means of starting; by means of a gas start system, by means of a Huck’s starter vehicle, or by means groundcrew winding starter handles.

The fuel system is a main tank of 46 gallons with two 16 gallon wing tanks for a total of 78 gallons of fuel. Main Tank ON/OFF cock ON. Pull the T handle of the Port wing tank outwards and thus ON, Starboard wing tank is left OFF as a reserve. Throttle – Closed, Mixture control RICH (Fully back), All Magnetos – there are Main and Hand Starting Magnetos – OFF.

Now ready to use the complicated gas start system. The system works by means of compressed air and vaporized fuel turning the engine on start up. Mags OFF, Gas Starter Master Cock OFF. Next the Drain cock of the starter vaporizer is opened by the crew and I will then unscrew the plunger of the gas start, which looks like a second primer above the main priming pump. The pump is operated about 6 times – or as long as it keeps squeaking - until fuel flows from the vaporizer drain cock, it is then closed by the groundcrew and the gas start priming pump in the cockpit is locked.

Next the engine is fuel primed with 5 or 6 “good strokes” - i.e with pressure. The Gas Starter Master Cock down on the cockpit floor is turned ON. Call the crew “Clear”. Hand raised and signal winding and “Contact”. Switch on and operate the hand starting starter magneto switch, then furiously wind the handle of the hand starting magneto and then depress the Gas Starter Press Cock with my right heel. As soon as the engine fires, the main magnetos are switched ON and the Hand starting magneto OFF, the Gas Starter Master Cock is then closed. As a coordination exercise it is like patting your head and rubbing your stomach whilst still needing your third arm to scratch your back. That’s all there is to it.

The alternative starting methods can be just as daunting initially. Seeing a Model T Ford based Hucks Starter vehicle pull up in front of your propeller and connecting up to it is an alien experience for those of us who try to keep everything away from our propeller arcs. After the Hucks Starter has been engaged into the propeller Fuel ON, Magnetos OFF, throttle open slightly. Prime 6 “good strokes”. Ready to start, “contact”, Hand Starting Magneto Switch ON, wind the handle of the Hand Starting Magneto as the Hucks shaft turns the propeller. As soon as the engine fires the main magnetos are switched ON and the Hand starting magneto OFF. The Hucks shaft releases as the engine fires and then the crew reverse the Hucks away. I would add that the Hucks is chocked so that it cannot go forward into the propeller.

The antique-looking Hucks Starter Vehicle backs quickly away from the Hawker Nimrod as Howard Cook works to keep the 12 cylinders of the Kestrel firing and to get it running smooth and eager. One wonders whether such a jalopy was ever employed aboard His Majesty’s Royal Navy carriers. Photo: Randall Haskin

There is the third option of having the groundcrew hand wind the propeller. This is by means of two starting handles connecting each side of the Kestrel engine. This is available as a back-up option if the gas starter is u/s or a Hucks is not readily available!

Warming Up

What a sound! Initially warm up at 600 rpm and check the Oil Pressure is rising. Open the throttle gradually between 1000-1200 rpm taking care not to long idle. It is necessary to avoid running at the gear or crankshaft “periods” of 820, 1080 rpm and about 1200 rpm. With the Oil temp at 15ºC and Water Temp at 60ºC, Magnetos are checked for a slight drop and then the slow running is checked. The radiator vanes are opened and verified open by the groundcrew and we are ready to taxi.

A last look round the taps and numbers and signal "chocks away". Check the brakes; left, right and both. K3661 has a pneumatic differential brake system that helps considerably with the need to be a practical aeroplane and to suit modern airfields and hard runways and gives good confidence in the aeroplane. The brakes are activated by using the converted gun triggers on the stick. This is the most notable improvement from the Nimrod I. Weaving the rudder to see ahead either side of the nose and the occasional hand-nudge of brake and up to the Duxford hold we go.

Checks before Take Off

Brakes on and engine check at 1400 rpm. The usual TTMMPPFFGGHH (See “Hurricane Season” in News Archive this site) before take off whilst keeping a close eye on the temperatures. It’s a biplane with the unique need in the display world today to watch coolant temperatures although it does hold its temperature well whilst on the ground with its radiator set permanently in the propwash.

T- Stabiliser Trim in Take Off position – 4 degrees down, Throttle Friction - tight Mixture Full RICH, Mags already checked, Fuel ON, Rad Flap - Open, Gauges, Gyros, Harness and Hatches.

With pre-takeoff checks complete, line up on the runway, taking care to check the sight picture off of the nose to both sides in preparation for any swing. Open the throttle smoothly whilst anticipating the swing to Port if the throttle is opened too quickly. The crescendo of noise that characterizes a liquid-cooled V-12, such as the Merlin, is taken to a whole new deafening level with the open cockpit of the Nimrod. At 21 litres, the very rare Rolls-Royce Kestrel up front is only 6 litres smaller than a Merlin. From stick back at the start of the run, relax and feel the force on the elevators, the tail gently coming up, the swing held well by the rudder (very similar to the feel of the Hurricane) and then maintain a slightly tail-down attitude. Taking the boost up to +2.5 to +3 lbs (+6 maximum) feels sufficient. With 600 hp up front, the 4,000 lb Nimrod goes off like the proverbial cork from a bottle in just a few seconds. This takes much longer to describe than it takes to accomplish!

Once airborne, hold the take-off attitude as the aircraft accelerates, check that the engine temperatures and pressures are all well within limits and get the boost back to +1.5 lbs. The climb attitude looks very flat from the ground but gives a rate of climb of 2000 ft/min despite the nose-low attitude. There is a 5 min limit of +1.5 lbs boost with throttle at the gate.

General Handling

Throttling back to Normal Cruise at -1.5 lbs boost the airspeed settles at 140 mph. Keeping an eye on the maximum oil temp (90º C) and the max coolant for the cruise (also 90º C), fly north clear of Duxford to get some height for the general handling phase.

Throttling back the Kestrel does not feel a very comfortable experience. It has a light wooden two-bladed propeller that, at idle, turns so slowly that one can feel the engine telling you that it does not like it. However we need to stall and must get the aeroplane slowed down.

As the engine protests at being taken back to idle it is better to keep on just a trickle of power and there is just a slight airframe buffet and thus little warning occurring before the impending stall, a “Hurricanesque” tendency. The nose drops with a slight wing drop, at as estimated 53 mph. I then flew some tight turns for some accelerated stalls. Again there is little warning of departure but a quick recovery is achieved with the aeroplane “unloaded”.

I set up for a brief aerobatic sortie with my primary concern not to exceed the rpm and boost limitation at high speed. No help like the Hurricane’s Merlin has with its Constant Speed Unit to assist the engine-handling. The Kestrel is such a rare engine that great care must be taken with the engine limits. Although it is a supercharged V-12, its fixed pitch propeller requires Tiger Moth- rather than Spitfire-like engine handling.

Howard Cook puts the Hawker Nimrod II through some basic handling exercises to get a feel for the flying qualities of this historic aircraft. The large two-bladed propeller is as evident in this shot as in the historic shots above. Photo: Peter Green/www.bomberflight.com.

The minimum recommended speed for entry to a loop is 170 mph. Starting with a series of wingovers and 360s, I used 180 mph to be on the safe side and flew a number of wonderfully smooth barrel rolls with one eye on the boost and rpm throughout. Looping felt less comfortable – just like a Hurricane! The Max Permissible Diving Speed (Vne) is 215 mph and there is a 5 minute limit of 2,900 rpm although I was well within these numbers throughout. In present times, such rare aeroplanes as the Nimrod II do not have to do 300 mph terminal velocity dives or inverted spinning with floats as they would have done back in the 1930s.

With the aerobatic sequence complete, it’s time to return to the airfield. I usually finish each sortie with a display practice in the overhead to make the best use of airborne time. I am often advised that the visitors to Duxford look up to expect a Spitfire diving in to the overhead to be surprised to see the beautiful silver biplane – to quote Flying Legends commentator Bernard Chabbert - “snarling”. It is a shared joy with my view being the Kestrel ahead and looking down on the magnificent silver Hawker wings with Duxford below.

Howard Cook, flying the Hawker Nimrod II, formates on a sister Hawker - the Hawker Hind, a two-seat bomber variant of the Hawker line, at Flying Legends 2008. Photo: Peter Green/www.bomberflight.co

Run and Break to land

All too soon the routine is complete and with a last pass at 100 ft pull up and turn to wash the speed off in the break up to the downwind. Keep the aeroplane tight in to the circuit in case of engine failure.

BUMPFHH; Brakes OFF and check supply pressure sufficient, Undercarriage is already down of course – but don’t assume as you could be in a Hurri next time! Mixture Fully RICH, Fuel ON, Harness and Hatches, “Nimrod Downwind to land”. Power back, although the Kestrel does not like it, the speed at the end of the downwind leg should be 80 mph. Abeam the runway threshold, start the curved approach à la Spitfire although the view ahead does allow for a more straight-in approach if required. With the engine throttled right back, you are watching a lazy windmill unhappy to be so slow, so it is best to keep on a smidgen of power. Keep the curve going and then straighten up and into the flare still keeping a touch of power on. If the power is cut too soon, the nose will drop – the same as with the Hurri. Flare into a gentle tail-down wheeler, wing down for the crosswind, cut the power and keep the tail off of the runway for as long as is possible with progressive forward stick until the tail drops, then stick hard back and keep it straight, fingers ready on the brakes. The nose wants to go left or right without reason and it is a matter of anticipating the swing with the quite excellent differential brakes. To quote Charlie Brown, they are “the making of the aeroplane”.

Howard Cook arrives back at Duxford after putting the Hawker Nimrod through its paces. The name Nimrod is in fact a Biblical name -- the great-grandson of Noah. He declared himself a "mighty one in the earth," founded the great city of Babylon, and presided over the construction of the mythical Tower of Babel. Nimrod was also a renowned hunter, though some claim his game of choice was not animals but men. Photo: Damien Burke/HandmadeByMachine.com

Taxi back to dispersal whilst keeping the usual close watch on temperatures and weaving to see the way ahead. Pull into the bay that the crew have marked, just in front of Duxford Tower and then into the shutdown checks. Chocks in, Idle rpm, magneto dead cut check, mags and fuel off. A key safety check after shutdown is to depress the Gas Starter Press Cock to confirm it is not Live. All done. Wonderful.

What a privilege to fly one of the world’s rarest fighters and such a classic type in aviation history, all thanks to HAC Principals Angus Spencer-Nairn and Guy and Janice Black for the opportunity to do so. Having seen the aeroplane through all stages of its resurrection, I know and appreciate more than most what a truly incredible job it was to get the Nimrod back in the air again after so long an absence.

The most beautiful biplane ever to fly? Beauty is in the eye of the beholder except that in the case of the Hawker biplanes it is in the eye – and the EAR – of the beholder. Watch and listen to it fly – and then tell me it isn’t!

Howard Cook, 2008

Howard Cook after his flight in the historic Hawker biplane. There’s no doubt that he enjoyed Nimrodding around the Duxford sky though the weather was closing in. Photo: Randall Haskin

Basic Characteristics of the Hawker Nimrod

Length: 26 ft 5 in (8.09 m)

Wingspan: 33 ft 6 in (10.23 m)

Height: 9 ft 8 in (3.00 m)

Wing area: 300 ft² (27.96 m²)

Max Take Off Weight: 4,050 lb (1,841 kg)

Powerplant: 1× Rolls Royce Kestrel V inline piston engine, 600 hp

Endurance: 2 hours

Maximum Speed: 168 knots (194 mph, 311 km/h)

Service ceiling: 28,000 ft (8,535 m)

Armament: 2 × forward firing fixed .303 (7.7 mm) machine guns

4 × 20 lb (9 kg) bombs on underwing racks