GLORIOUS FUN — flying the WACO Taperwing

As I walk up to the WACO on a sparkling day in June, light reflects off the rich, crimson, and glossy paint. This airplane is a jewel flashing in the sun! But my next impression is its size. I’ve been flying Tiger Moths and a Fox Moth, and they are delicate creatures by comparison. CF-BPM is fronted by that big Wright Whirlwind with its projecting cylinders and huge 9-foot propeller - the whole airplane follows from that. It is a solid, old-fashioned, grassroots barnstormer, promising to be loud and oily and require a firm hand. True, it doesn’t disappoint in that, but I also find that the WACO is a marvelously responsive creature, reacting instantly to a delicate touch, and this is a delightful reward.

I throw my helmet in the cockpit, make sure the magnetos are off, and begin the pre-flight. The front cockpit has the metal tonneau cover on, improving the airplane’s looks considerably, making it appear racy and aggressive. I stand on the wing and make sure that the tonneau cover is well secured. I don’t want it coming loose in flight and taking off my head. While on the wing I check the oil (a 5 gal tank, no dainty creature this!), and fuel (60 US gal, giving a 4+ hour range – more than I’ve got). I follow that with a standard walk-around until I get to the engine.

This Wright Whirlwind is a piece of history. Its older brother, the J-5, took Lindbergh to Paris. In 1935, this airplane sported one. Since then it’s been upgraded. This is a J-6, (which technically makes the airplane a CTO, but never mind that) and the development of these engines was the development of air-cooled radials. They were the first to achieve proper cylinder head cooling, and their sodium-cooled exhaust valves were a revolutionary innovation, allowing unheard-of reliability. All the giant round engines of WWII, the huge R-2800s and even larger Wright 3350s stemmed from the solutions pioneered by the J-Series of the 1920s.

But my thoughts are more prosaic. I’ve got to make sure oil hasn’t collected in the bottom cylinders overnight. If left undrained, it could break a connecting rod during engine start. I check, and sure enough the maintainers at Vintage Wings have opened the convenient Wright drain-cocks in the bottom two cylinders. I take hold of the prop, wincing as my fingerprints mar the perfect surface polished by Anna Ragogna, our “Lady of the Gleam”, and I pull the blade left to right under the engine to the other side. I hear a wheeze as a valve opens and compressed air flows. A mag impulse clicks. I pull and pull and pull, until fourteen blades have passed. (I remember to close the drain-cocks!)

The heart of the WACO is its hearty Wright Whirlwind J-6 engine and polished Hamilton Standard propeller. The robust landing gear shock absorbers complete a tough look. Photo: Peter Handley

I kick both tires. They are extremely tall. The tire size is 5" x 30"! And the supporting oleo structure is massive and attaches halfway up the side of the fuselage. Obviously this airplane was designed for rough fields! Sure enough, the Weaver Aircraft Company (WACO) hoped it would replace the First World War surplus Curtiss Jennies that began the barnstorming era. It had an undercarriage designed to land in any cow pasture next to the ubiquitous county fair. And two seats up front to collect twice as much revenue per flight.

The rest of the walk-around is standard. I take particular care to inspect the underside of all surfaces. If I bring it back with a rock-puncture it will be me, the last pilot who flew it, who takes the blame!

I hop in and get organized. The cockpit is quite roomy inside, though the opening isn’t. There’s no place to set anything of course. Maps and flight supplements have to be stuffed in flightsuit pockets. The upper part of the panel is turned-metal, like the dash of a Bugatti. Below that is a rack of radios and electrics.

The start is straightforward, if smoky. There’s no fuel pump switch, just a mixture control and a primer. I give it six strokes – I have yet to over-prime this engine – hold the brakes with my feet, crack the throttle, hit the starter, count two blades (less chance of kick-back if the whole mass is revolving), and switch the mags on. If it has enough fuel it starts, and if it’s been in the hangar a few days there’s usually a belch of oily smoke as the exhaust gets cleaned out. The large white cloud brings a concerned look to the ground crew standing by with the fire extinguisher but it dissipates rapidly.

The secret to round-engine longevity is “warm-it-up, and cool-it-off.” No rushing. Thus I sit for three to four minutes as the cylinders warm to their designed tolerances. This is a useful time, and I use it to prepare for the flight. A panel check is simple – there’s hardly anything on it. The altimeter has only one pointer. It’s the non-sensitive type. It reads in thousands, and trying to see hundreds requires reading the small gradations. It has a setting bezel which turns the whole face, not just the needle! (I also set the other one lower down that feeds the transponder, the modern one, feeling slightly guilty.) I use the remaining time to mentally rehearse the flight. My objective here is to test fly the aircraft for our Open House event coming up soon, and get myself current again after a long snowy winter. I think about what I’m going to do…

I offer a thumbs-up to the ground crew and taxi away. A quick brake check is important since I can’t see ahead at all. I could boost myself up with cushions and improve the view, but then I’d be too tall in the seat for flight. Might as well get used to it. The airplane has good tailwheel steering anyway, so S-turns are simple.

The brakes are much better now! They used to be awkwardly mounted. My feet were always getting caught on the hardware for the front seat. I found out the restoration was originally for Rob Lock, a 6’9” NBA player whose endless legs required an odd geometry. Later this was modified, very poorly, so during the winter I got involved in taking it all apart and re-installing the pedals from scratch. Now they’re designed to be worked by normal humans! (Or at least by me.)

The run-up is simple since the prop is fixed pitch. I taxi out to the pad at Gatineau and line-up into the wind. The brakes will hold at 1600 RPM. The engine makes that unique early engine sound, a deep brrrrr… combining the efforts of the 7 big cylinders plus that extra-long prop. The mag drop is within 100 on each side. The carb heat hardly makes a difference. Not much more to it.

A couple of things are important on the Pre-Take-Off Check: the trim must be set and firmly latched. It inclines the whole horizontal stabilizer (not a tab), and it’s unstable. It wants to zip! to full-up or full-down. I’m careful to make sure it’s solidly latched. And later, when lined-up, the tailwheel should be locked straight. That’ll help keep her straight later at touchdown.

Eyebrows go up all over the field as I taxi across the runway and veer into the grass on the other side. (Is he lost? Is there a problem?) But I revel in it! There’s nothing that steps you back-in-time like trundling a big biplane through the grass on a bright summer’s day. As I backtrack, weaving back and forth so I can spot groundhog holes, divots and soft spots before I get embarrassed by them, the very large tires easily handle the slightly uneven ground. Brakes are no longer required, and the airplane feels at home. The world of modern aviation seems quite removed. The first owner of this airplane (famed aviator Johnny Livingston) was a friend of Charles Lindbergh, and it feels like the two of them are back at the hangar, waiting for me on my return. I like this feeling very much.

With her polished blades flashing in the sunlight, Dave Hadfield taxies the WACO out to the runway. Since she was built in 1929, the Vintage Wings WACO has been flown by many including NBA basketballer Rob Lock, who went on to become a vintage aircraft collector and restorer. But none was more famous in their day than Johnny Livingston (Inset) the WACO's first owner and pilot. Livingston was a household name in the 1920s and 30s as a high-flying air racer. Photo: Pierre Lapprand

We’re fortunate at Gatineau to have almost 100 ft width of useable grass. It isn’t perfect – it slopes a couple of degrees to the north – but all the taildraggers are happier there. (The slope is never a problem except in the pilot’s mind.) I line-up in two stages, first with about a 30-degree cock to have a good look for traffic in all directions, and then to the runway heading. I DO remember to lock the tailwheel, once straight.

It’s the sound of the Wright Whirlwind that I find most delicious. It has the most wonderful swelling “Rummm…ble” as the RPM builds up. The big prop doesn’t have to swing fast – about 1800, static – but the pull is serious and immediate. As long as the tail is still on the ground tracking is straight and steady. You can’t see, but that’s not important on a 100 ft wide strip of green grass, or even pavement. You can feel yaw in your back and buttocks, and peripheral vision helps a bit. The WACO stays mostly straight. But this stage can’t last forever, and you smoothly move the stick forward to ease the tail up. Immediately there’s a yaw to the left, but you were expecting this, and your right foot has lots of authority.

A straight-wing WACO would get off the ground almost immediately, but this one has the tapered wings, so it takes us a little longer. An interesting feature of these early WACOs was wing-interchange. The outer panels just bolt-on. After a few years of flight with tapered wings, this aircraft was used on floats, and for that it had the large, high-lift, straight wings installed. Nevertheless, it doesn’t take long to lift off, and at light weights, the climb rate is brisk. We ease the power back to 1750 and climb at 80 mph. A gentle turn north and we head to a practice area.

Related Stories

Click on image

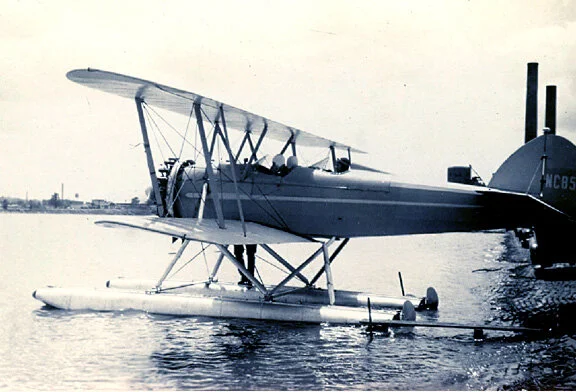

Back in the day, the Vintage Wings of Canada WACO was flown on floats in the USA where it was registered as NC8531. During this period, the Tapered wings were exchanged for Standard chord wings turning the WACO ATO. into a WACO ASO - the extra wing area being required for float operations. Today, she's back on her sleek ATO wings. Photo of NC8531 via National WACO Club

The ailerons are a delight. There's no other word. They’re mounted on bushings and on the ground that makes them stiff, but in flight they are effortless. With four of them controlling those small, tapered wings, the airplane cavorts on a wingtip at the slightest pressure. I’m impatient to get out of the circuit so I can start.

There’s a small valley northeast of Gatineau with a few decent fields I could use if the engine quits, so I climb up that way. I relish the cool air flowing over my face, the deep low-rpm sound of the Whirlwind, the sun sparkling off the chromed flying wires. When at 5,000 ft, I get a clearance from ATC for air work, and I can turn the damn radio down. (Radios in open cockpit biplanes either fail utterly or are scratchy and hard to read. It’s some sort of a Cosmic Law.)

I ease the power back to let the cylinder heads cool from the climb. I stand on one wingtip and let the earth revolve as I check for traffic. Then around the other way, same thing. And then I do indeed cavort! I lower the nose and let the speed build. At over 110 mph the flying wires make the most wonderful wail. It’s like a Hollywood sound-track, a rising-pitch scream. The RPM stays well below it’s rated 2,000, so I can leave the throttle alone at climb power. At 130 mph I bring back the stick (the controls take a good firm pressure in pitch, just enough to allow smooth application of “G”) and roll at the same time for a Lazy 8. The nose comes well up above the horizon, and at 45 degrees into the turn I relax the back-pressure while continuing the roll so that at 90 degrees of turn the nose goes downward through the horizon while the bank is almost 90 degrees. Then the recovery phase, rolling out to zero at the 180 point with the nose coming back up through the horizon. Actually, this is not too difficult. What takes fine tuning is the rudder! The ball should be in the centre during all of this, and it wasn’t! I grimace, relax my shoulders, “fe-ee-eel the yaw”, and do it again. And again. And Again! I keep revolving over the Gatineau hills until the grimace is replaced by a grin of sheer delight.

The Taperwing in flight over the Ottawa River Valley - green farmland and glorious fun. Photo Peta Cook

Next some slow flight. (Any damn fool can fly fast. It takes skill to fly slow.) I leave 1600 rpm on, and bring the nose up. The airplane drops to an IAS of 52 mph. I roll into a turn. I have to nurse the stick fore-and-aft, gently tugging and nudging it, riding on the edge of the stall. The least coarseness and the WACO will protest by dropping a wing and attempting a spin (which is why I’m at 5,000 ft). I roll back the other way. The ailerons are sloppy and loose at this speed and high angle of attack, needing a big movement, but the tail feathers are in the slipstream, and thus I have lots of control in pitch and yaw. It takes a considerable pressure on the right rudder all the time. To keep the ball centered as I roll left, I don’t add left rudder, I just relax on the right one. I weave back and forth, seeing how close I can get while rolling more and more aggressively. I’m amazed at how controllable this airplane is, at high angles, for a 1929 design. Some slide-rule guy did his homework! Finally I deliberately tug too hard in a climbing turn, the Waco washes her hands of me, and the upper wing stalls and sharply drops. A quick hard application of opposite rudder and she recovers on an even keel, nose on the horizon – or what I can see of it, obscured by those lovely black-painted Whirlwind cylinders.

And so twenty minutes pass in glorious fun. Neither the airframe nor the engine are approved by Vintage Wings of Canada yet for full aerobatics, so I limit us to chandelles and Lazy 8s and wing-overs and combinations to my heart’s content. I do NOT accomplish a series of barrel rolls, first left and then right, swinging the nose through a figure 8 on the horizon spanning about 120 degrees of heading change, with 1400 rpm on the engine for gradual cooling, while I lose 2000 ft of altitude as I point back to the field. The grin on my face is purely coincidental.

Dave Hadfield (Inset), manager of biplanes at Vintage Wings of Canada cavorts in the blue skies over the Ottawa River Valley. Photos by Peter Handley

Too soon it’s over. I turn up the radio and push the button, “Gatineau Radio, Fox-Bravo-Papa-Mike, Waco Taperwing [I love saying that!], 5 northeast, 1500, inbound.” I aim east of the field a mile or so and then join a straight-in left downwind for 09, “The grass.”

I hate “Cessna circuits” in a blind airplane. A long straight final means you can’t see where you’re hoping to land. This is not optimum! But fortunately I’m the only one in the pattern, so I can plan an old-style continuous descending turn to the runway. There isn’t much of a check to do – the gear is down and welded, and there’s only 1 fuel tank, but I make certain to double check the tailwheel lock. If I had forgotten it at takeoff, it would be a good thing to know now, especially if I was landing on pavement.

Dave Hadfield crosses the grass infield to check the field conditions prior to landing at the Gatineau Airport. Photo: Eric Dumigan

There’s a certain sight-picture formed by the rigging wires beside the fuselage. It’s a triangle, and if you manage the rate of turn to keep your touchdown point centred in that triangle, it works out perfectly. Abeam the touchdown point, as I roll into the gentle turn, I bring the power back, but not to idle. This airplane can develop a huge sink-rate if the power is off and the speed gets back. I keep a trickle on, widening the circle a bit to compensate. It’s also good for the Wright to not be cooled too suddenly. But if it quits suddenly, I can always tighten the turn and still make it over the trees.

While at 90 degrees to the landing surface I evaluate it, looking for ditches and lawn mowers and whatnot left in the grass, and I adjust the rate of turn to maintain a desired path. Airspeed is 80 mph on the dial for now. The sound of the airplane has diminished. The engine is back to a low rumble and the wires are quiet. With a bit of familiarity I can judge speed on this airplane pretty much by sound and feel – good, because near the ground I need to have my eyes outside the cockpit.

I’m helmeted and goggled, but there’s little breeze on my face. The canopy is quite protective. Then, as I get close I see a brown patch in the grass that concerns me. I quickly yaw the nose to the right and instinctively hold bank the other way, sideslipping, so I can see more clearly. The slipstream pushes hard on my left cheek. I’m banked more than the rudder counteracts, so my gentle turn has increased to a slipping turn. I dismiss the brown spot as just a bit of dead grass, not a section of plywood, and relax into a coordinated turn again.

I roll out in a high flare, power right off, easing the stick back. The gear on the WACO is perfect for a 3-point landing, allowing a full-stall on all 3 wheels. That’s my plan. Visibility would be better with a wheel-landing, but with 100 feet width of grass, I don’t really need visibility. Also, any wheel-landing is a bit dodgier than a 3-point, especially if there’s a patch of mud ahead. A wheeler allows you to see, certainly, and have a bit more control at touchdown, and can more easily open the throttle and fly away again if something goes awry. But if you touch on all 3 points in a full stall, AND THEN LOCK THE STICK BACK AND LEAVE IT THERE, the airplane is all finished flying and will transition to a earth-bound vehicle with a minimum of fuss. And if you hit a mud-puddle, so what? With the tail down you’ll just bounce through it.

As I come to within a few feet of the ground the nose is up and all forward visibility is lost. My eyes flick left-right-left-right. As long as I’m approximately centred between the hard-surface and the ditch, I’m OK. The stick comes back, and back, and back as I hold her off. I’m trying to judge it at just 6 inches or so. Finally the stick won’t come back any further and we settle onto the ground with a little plop. I’m alerted and focused at this point. My senses are on the qui-vivre, ready for the first sign of yaw. In any taildragger, the secret to survival is instant detection and instant correction – don’t let the swerve get established! There’s a rattle from the landing gear as it chatters over the little tussocks of grass. My feet are ready to dance on the pedals. If I feel any yaw in my back and legs and butt, I’ll be on it like a hammer on a nail, but today nothing is really needed. We roll along with a couple of skips, settle into the groove, slow down to a fast taxi, AND I RESIST THE TEMPTATION TO RELAX. I let the airplane stop. Then and only then do I unclench my buttocks. Most ground loops happen at the end of the landing roll when you think you’ve got it made.

A look of satisfaction crosses the face of Dave Hadfield as he taxies back after a joyful and exhilarating flight in the Taperwing. Photo: J.P. Bonin

The world has stopped moving. The engine is idling and I see a dandelion beside me bending in the prop-breeze. This will never do! I release the tailwheel lock, pivot around using power and rudder, and back-track for another whirl. The morning is yet young and the airplane and I are only nicely warmed-up! Off we go, again and again…

It’ll be a long time before I get tired of this airplane.

Likely never!