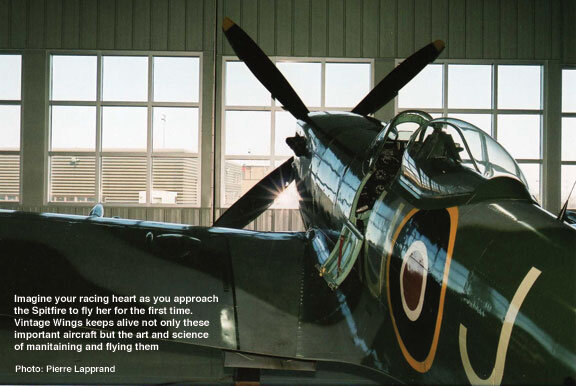

JOHNNY SPITFIRE

John Aitken thought he had dodged a bullet, or rather a bucket. On June 18th he soloed in the Vintage Wings of Canada Supermarine Spitfire Mk.XVI. When he taxied in and stepped down onto the ramp, he must have wondered if anybody had noticed at all, for the traditional tsunami of icy Quebec water down the back of the neck was not forthcoming. Problem was, it should hit you when you least expect it and our maintenance gremlins who traditionally (at VWoC anyway) do the dirty deed, found they had lost the advantage of surprise necessary to make the rite of passage a more satisfying one for the those watching.

Not quite sure whether he was happy to be dry or spiritually shortchanged, John walked to the office to complete the necessary paperwork. Aitken simply logged the hour, made his report and looked forward to the next day when he would continue to extract experience and knowledge from the Spitfire while taking it through his rigourous test program.

During the war years, Canada was graduating qualified war bird pilots at a phenomenal rate. Back then they were inexperienced novices who were flying the hottest aircraft in existence. Many didn’t make it through their training. Teaching and graduating Spitfire pilots became a lost art. Prior to Vintage Wings of Canada, there had been very few made-in-Canada Spitfire pilots in decades. Vintage Wings has changed all that. Since Mike Potter first took delivery of his Spitfire in 2000, we have graduated six new Spitfire drivers, three new Mustang IV pilots, 3 Hurricane pilots and two new Corsair pilots. Soon we will be graduating Fairey Swordfish, P-40 Kittyhawk and Westland Lysander pilots as well.

Like the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Vintage Wings of Canada keeps its pilots sharp through currency training on the de Havilland Tiger Moth and the North American Harvard. Unlike the BCATP, Vintage Wings pilots are extremely well qualified with thousands of hours on many types. Almost all have jet time and many have flight test experience enabling them to sense and understand the latent and sometimes dangerous idiosyncrasies of these exotic birds.

Perhaps the pilot with the most test-flying experience is Aitken who recently retired from the National Research Council’s Flight Research Laboratory where he headed the facility’s flying operations. This deep well of knowledge would enable him to strap into the Spitfire with a degree of confidence not available to the pilots of the Second World War. But all the experience in the world could not obviate the rising excitement John felt as he unleashed the Merlin and thundered down the runway for the first time lifting off into the same Canadian skies that once belonged to the great aces and line pilots of the war. Looking out over that magnificent elliptical wing of the Spit during his turn out, John felt the same pride of accomplishment and the same thrill at the raw power in his left hand as any 22 year old RCAF pilot from the war – the main difference being that Aitken’s flying skills equaled his confidence.

Here in John’s own words are some of his observations of his first two flights in one of the world’s greatest airplanes:

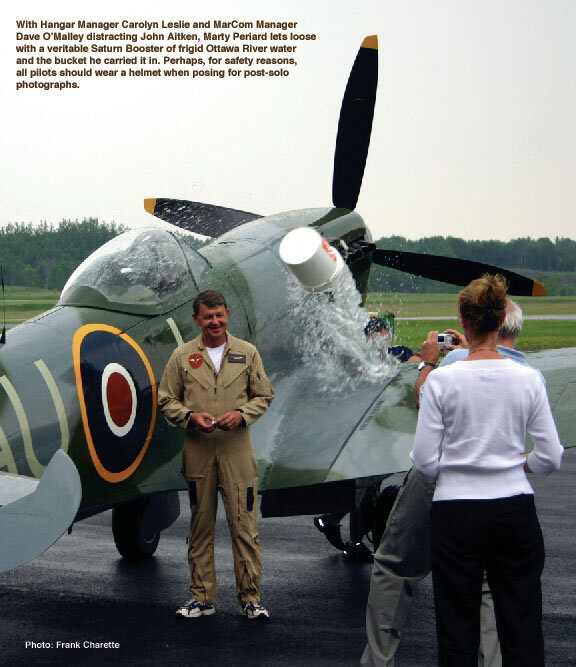

There are not too many instances when being doused with a large bucket of icy water is an event you enjoy – especially when you are surprised and fully clothed. But milestone events in military aviation are often water events – your first solo, your last mission, your 1,000th hour on type – that sort of thing. More often than not, the water comes from an airfield fire hose, but at Vintage Wings of Canada, firsts are celebrated with five gallons of icy, cold-filtered Ottawa River water to the back of the neck. After his first solo, soaked only in his own sweat John walked back alone to the operations room at the hangar resigning himself to a hot shower at home. The trap was set.

“Perfect”, thought deviant maintainers Andrej Janik and Marty Periard. “Tomorrow he won’t be looking over his shoulder, awaiting his due”. And so the next day, for John’s second flight in the Spit, the bucket was full, the bucketeer Periard was ready and hiding as John rounded the taxiway to the ramp. John’s attention was held for just enough time to get Marty in position behind the wing. It was not a perfect throw by any means. Periard usually employs the time honoured “sneak and sweep” technique for bucketing, but with the wing in front and John more than ten feet away, he attempted a throw with a high degree of difficulty – a classic two-handed over-the-wing side-arm shot designed to launch the water in an arc over the wing. Unfortunately he hadn’t practiced the throw in over two months and neglected to release the handle at the right moment. This meant that most of the water splashed on Marty and the wing, followed by the half-filled bucket arcing towards John’s head.

Luckily, the bucket fell short of ending Aitken’s brilliant Spitfire career and John received just enough water to complete his baptism - in the name of the farther, the sun and the Holy Spit, we baptize you Johnny Spitfire.