NIGHT SCRAMBLE

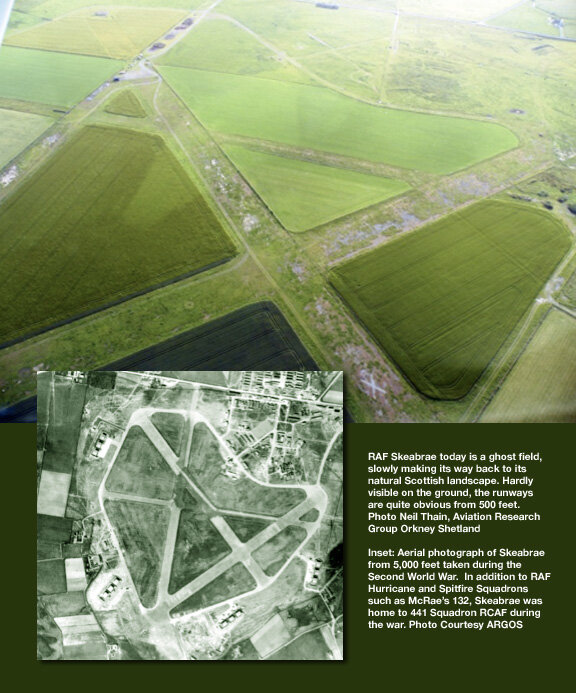

The entry in my log book reads simply: “Scramble - 32,000’ - 45 minutes - night”, but it was an experience I have never forgotten. Today's all-weather pilots would consider this little adventure a joke, and even I would not have thought much about it a year later, but prior to this flight I had logged less than 300 hours total solo, of which only 10 hours were at night in the Spitfire, (I had two hours solo night in my log book when I first flew the Spit ) and less than 16 hours total actual instrument time.

The Spitfire was a pleasure to fly - in daylight - but some of the fun wore off when it was flown at night. Three exhaust stubs each side (on the Mk. I’s, II’s and V’s), almost at eye level, combined with a curved windshield to play tricks with your night vision. We had no navigational radio, and without ground reference were totally dependent on Ground Control Radar for vectors home. This was not GCA, (Ground Control Approach), they only brought us, hopefully, near enough to a field that we could find a beacon. I should add that flying over wartime Scotland on a moonless night was similar to having your miner’s lamp fail while underground in a coal mine, (a comparison I make from experience!) The compass on a Spitfire was situated under the instrument panel, directly behind the control column. Awkward to read in daylight, it was almost impossible at night. Of course we had a full blind flying panel, but I soon came to distrust the artificial horizon; invariably someone before me had done aerobatics with the instrument uncaged and I would find it with a permanent list. All my early instrument flying was done using the references on which I had learned in the Tiger Moth, needle, ball (or in the case of the British aircraft, needle, needle) and airspeed.

We had begun night flying in January, 1942, in Mk.IIb Spitfires and initially experimented with a number of different lighting systems. Basically there was a single line of hooded flares down the left side of the runway. Usually these could not be seen until lined up with the runway, which limited our use of the usual curving approach. With just one line of flares and the Spitfire’s poor forward visibility on the ground, landing too far to the left could mean losing the flare path, and energetic braking was necessary to bring it back in sight, (the Spitfire’s rudder was ineffective at low speeds). One system we tried consisted of a 3-light glide path which again was only useful with a straight-in approach. A red light indicated you were too low on approach, a white light too high and a green light indicated`on glide path’. In order to see these lights on a straight approach just about everybody came in too fast. In combination with the glide path, a large flood light was parked just off the approach end of the runway. As soon as you crossed the threshold they turned on this flood, which lit up the runway like day, but it also cast a terrible glare from the inside of the curved windscreen. The flood was left on only until you touched down, but when it was turned off you were totally blind and it took several seconds before the flare pots could be picked up. We had so many cases of running off the end of the runway through landing too fast, or running off the side of the runway to nose up in the mud, that this system was soon dropped.

164 Squadron Spitfire at Skeabrae in 1942. The Spitfire was pleasure to fly, even in the remote and cold Orkneys, but night flying was another matter. Photo courtesy Aviation Research Group Orkney Shetland

Members of Bill McRae's A Flight of 132 Squadron RAF at Skeabrae. A young Bill McRae stands in back, second from right. Photo via Bill McRae

When the German warships Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen broke out of Brest we received orders to move to Skeabrae, (sometimes referred to as Skara Brae) on the Mainland island of Orkney. Orkney comprises a group of about sixty-seven islands, the largest is Mainland, followed by Hoy. Enclosed by Mainland, Hoy and smaller islands joined by causeways lies the main deep-water British naval base of Scapa Flow, housing the Home Fleet. We assumed our move was intended to bolster the air defences in the region, in the event the fleet was called upon to move out against the German vessels now on the loose. We immediately began keeping two or three machines standing by on readiness each night. This chore was done on a rotational basis, so my turn did not come up too often. Only one pilot was on immediate readiness, and only one was sent off if a scramble was called for. We lost a pilot on one of these night operations, a young Englishman who had just recently joined us. He had been scrambled to investigate a `bogey’ on the radar screen approaching over the North Sea from the east. As so often happened, the bogey disappeared from radar and our man was given a vector to steer for base. He acknowledged the instructions, but to the controller's dismay the blip on the screen described a reciprocal track, moving east away from Orkney, (a compass error we referred to as `putting red on black’). Radio calls went unanswered and our Spitfire simply disappeared off the screen and was lost.

On the night of this story, I was sitting in the dispersal with a couple of other pilots, with my Mae West on, as I was the immediate readiness pilot. It was raw and raining, and all three of us were huddled around the pot bellied coal stove trying to keep comfortable. We were making toast on a long-handled toasting fork and liberally lacing it with margarine, one of the few extras we were allowed when night flying. The phone rang, someone answered it and yelled "scramble". My Mk.V Spitfire was right outside the door, so I was out and in it in seconds, probably even faster than usual to avoid getting soaked. I started up, set the oxygen flow to 5,000 feet, taxied carefully out to the end of the runway and lined up. Normally we took off with the canopy open and the small side hatch on half-latch to prevent the canopy from closing in a crash. Sometimes unlatching and closing this hatch again could be a struggle, something I didn’t want at night, so I closed the canopy before taking off. It was black as ink, so I was on instruments as soon as I selected wheels up, and I was in cloud at about 300 feet.

"It was black as ink, so I was on instruments as soon as I selected wheels up, and I was in cloud at about 300 feet." Photo illustration Dave O'Malley

As soon as I felt comfortable in the climb I called the ground controller who directed me to climb on a south-easterly heading to "Angels 32", which meant 32,000’. This would take me over Scapa Flow and out over the North Sea. I opened the oxygen valve full. The cloud was solid until I noticed it lightening up a bit and then, at about 10,000 feet, I popped out into brilliant moonlight. As I kept climbing I could look down on a sea of clouds, almost like daylight; it was quite beautiful and belied the foreboding dark beneath. I had almost reached the height objective when the controller called to say the `bogey' had disappeared and ordered me to return to base. The same old story. I switched on the transmitter to acknowledge, and to ask for a vector to base, but to my dismay there was no sound. My transmitter appeared to be dead. When I gave no reply the controller called again, and again nothing happened. My palms began to get a bit sweaty, and I started into a circular holding pattern ; there was no point in going any farther out over the water than I presumed I already was, and the memories of that kid the previous month were still fresh. The controller was on his toes, because he now came back to say he was not receiving me. He had my position from my IFF, (Identification, Friend or Foe - the predecessor to todays’ transponder) but he had no way of knowing if I was receiving his transmissions. To confirm this he now asked me to fly a short-sided triangular course which would bring me approximately back to my starting point, save for the effect of any wind, the `lost’ procedure for radar. When I had completed this he came back on the radio giving me a westerly heading to steer and instructing me to begin my descent.

I came down quickly to the cloud top, then reduced the rate of descent before plunging in. When I was down to about 5,000’, he came on again to tell me that he was bringing me down "to west of base", which told me I would, hopefully, be coming out of cloud over the Atlantic and well clear of high ground. The Atlantic coast of Hoy has cliffs rising sheer for 1,000 feet. He also said that in the event he lost contact with me, which was quite possible due to the hills and my low altitude, that I was to fly a heading of....... and then gave me an easterly heading. I reduced my rate of descent again when I got to 2,000 feet and soon sensed rather than saw that I was out of the soup. Looking down I could see faint white streaks, foam from breakers on the Atlantic. I turned carefully onto the heading he had given me and it took me directly over the field. They were unable to find anything wrong with my transmitter and concluded that condensation from my breath had frozen on the diaphragm of the microphone, which was an integral part of the oxygen mask, preventing it from flexing.

We had so many false-alarm scrambles that we became rather cynical about the whole business, but post war research suggests that at least some of them could have involved German weather flights, photo recco or hit-and-run bombers. As late as the winter and spring of 1944 the Germans continued to probe the secrets of Scapa Flow. In February of that year a Me109 with a large drop tank was sighted over the North Sea 50 miles east of Orkney. Two weeks later two Ju. 88's popped out of low cloud in daylight to fly across the entire naval base, before zooming into the cloud again and escaping before

anyone could be scrambled.

Bill McRae, RCAF

Spitfire dispersal pens at Skeabrae are still visible nearly 70 years later. Perhaps it was from one of these that Bill's Spitfire was towed prior to his night flight. Photo by John Thain, Aviation Research Group Orkney Shetland

Bill McRae, the author, is a prolific and eloquent recorder of his experiences as a fighter pilot during the Second World War. Reading his remembrances, we view life in the RCAF of the Second World War through the eyes of one who was there. Many of his pieces (and there are more to be shared) have been previously published in the journals of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society. We have added only the photographs and illustrations. Ed.