INSPIRATION MACHINE

It had been a long week at work. My wife and I and Wallace the border collie were jammed into the truck with a weekend’s worth of gear, headed to the cottage. Ramping up onto the 417, westbound into the sun, we found ourselves in the last remnants of Ottawa’s somewhat bush league rush hour, soon coming up on a kilometre-long clot of stop and go traffic. Muttering to myself, I rolled down the windows to let Wallace sniff the gassy air. Squinting into the heat of a late afternoon freeway, and twiddling with the radio, I heard my cell phone vibrating from the cup holder in the centre console. Looking down, I read the caller’s name on the small screen: Todd Lemieux.

There’s a law in this province that says you can’t use a cell or text while driving, and well, I think it’s a law that makes sense, except, it was Todd Lemieux calling—a man you just don’t ignore for one very simple reason—he’s a prince among men. But having my wife answer the phone and hold it to my ear, well that must be OK. Surely there must be a “Todd Lemieux Clause” in that law. So I asked Susan to pick up and say hello. It was Todd Lemieux, so she didn’t need much prodding. A few salutations and she leaned across the console and jammed my iPhone up to my ear. From across the country, accompanied by his own road sounds, Lemieux and his two compadres, Gord “Gordo” Lemieux and Christie “Krusti” Whelan, were heading east down the rolling Trans Canada Highway towards Calgary, having just put the hard-working Harry Hannah Boeing PT-27 Stearman to bed in Bruce Evans’ hangar at the Springbank Airport.

“Howdy cowboy!” came Lemieux’s familiar salutation. “Hey Farm Boy.” I answered as I always do. From 2,000 miles away, masked by the rush of road noise on both ends, there was no mistaking in his voice, the timbre of exhaustion, the spark of happiness, the pride of a job well and safely done, and the giddiness of knowing you are just a half hour away from a well deserved cold beer at the Garrison Pub. “We got a car full of tired pilots and we just wanted to let you know that Harry’s Stearman is safe in the barn” offered Lemieux, “and we flew 52 cadets over the past week, 22 on one day alone. We’re happy and we’re heading home for a cold beer... maybe more.”

Over the next ten minutes, as Susan and I inched along through the knot of traffic, Todd, Gordo and Krusti yammered away excitedly and I could feel the energy and happiness that filled that car on the Trans Canada. Every ten seconds their car would explode with laughter as they poked fun at each other, causing me to laugh out loud with them. Susan had no idea what they were talking about, but she could hear the blast of guffaws coming from the phone and couldn’t help laughing and smiling along in that wide, beautiful way she always does. In one magical moment, the boys in Calgary had infected our stalled-in-traffic car with a heavy dose of good humour and happiness.

I had the immediate sense that these three tired Yellow Wings warriors were like three Drayton Valley oil rig workers heading into town to blow off some steam after a week of sustained and productive work, weak from their labours but strong of heart; like three boisterous Second World War squadron mates heading to the Eagle Pub in Cambridge to release the tension from their shoulders, to share the memories of the days past, to seek the company of others who know their joy. They were bound together in the manner of people who have just done something of great significance. They were inspired.

Some of the members of the Yellow Wings Stearman team at Netook, Alberta. Left to right: Todd Lemieux, Yellow Wings Team Lead; Gord Simmons, pilot; Fiona Stevensen; Derek Blatchford, pilot; and Krusti Whelan. There are many folks who make this program possible on the ground, including the Air Cadet League of Canada and the Department of National Defence. There are other key Yellow Wings pilots from coast to coast, but out in Victoria and Penhold, this included Ron Dujohn, Bruce Evans, Larry Brown, Norm Swayze and Jeff Bell. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

The Warrant Officer Harry Hannah Boeing PT-27 Stearman (Kaydet)—the Inspiration Machine. Of all the elementary flying training aircraft on the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), Kaydet, though a larger, more powerful biplane than the more delicate Tiger Moths and Fleet Finches also in use at the time, was in service for only a few months. The Kaydets were delivered for use in Royal Air Force (RAF)-run schools in Alberta only, but without many of the options requested by the RAF for instruction in the extreme cold of the Canadian climate—the most important shortcoming being the lack of an enclosed cockpit. Pilots were issued leather face masks to prevent frostbite in the slipstream of the open Stearman cockpit. Despite these problems, they were employed until much better equipped Fairchild Cornell trainers could be supplied. After 18 months, they were returned to the United Sates, where they served as USAAF trainers. RAF student pilots, who trained on the Stearman, look back fondly on the memory of this superb handling trainer and consider themselves amongst an elite group in the BCATP. The Vintage Wings Stearman, a rare BCATP veteran, wears the markings it once wore (FJ875) when in the service of the BCATP at No. 32 EFTS, Bowden, Alberta. Photo: Todd Lemieux, Yellow Wings Stearman Team

I guess you can say Inspiration is a two-way street. Like Newton’s Third Law of Physics, the job of inspiring young people to dream of accomplishing greatness creates an equal and opposite feeling of inspiration in the hearts of those exerting that force of inspiration. The task they had undertaken these past weeks, on their own time and at their own cost, was part of a magnificent idea of Vintage Wings of Canada to send their Second World War yellow training aircraft across this great land on a holy mission to take 500 young Canadians for a ride in a time machine. Teams of Canada’s finest pilots headed to places like Victoria, BC, Penhold, AB, Gimli, MB, Trenton, ON, St Jean and Gatineau, QC and Greenwood and Debert, NS—the task to inspire young people, to speak to them about the heroes of aviation who rose to greatness at a time in our country’s history when greatness was the only path back to light and peace.

These young people were exposed to the notions of duty and honour and a concept no one is willing to speak about in these days of entitlement—the meaning and importance of personal and national sacrifice. And what better stages to stand on to deliver this story, than the very training bases that pilots and aircrews trained at during the Second World War? Every Yellow Wings venue was originally built as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan between 1939 and 1942. All were home to training schools that did their best to provide knowledge and experience to what was then Canada’s finest young people. Despite the excellence of their training, the young men and women of that period could never escape the suffering, deprivation, injury and even death that were their immediate future. But the BCATP did equip them with the confidence and the inspiration to move forward and to achieve greatness in the face of inconceivable adversity.

Related Stories

Click on image

The BCATP, it facilities, its instructors, its communities and its aircraft were in fact a great machine, one that processed, pressed, milled, shaped, built and inspired heroes. Today, on the same fields, in the same communities, with a new stock of young Canadians and experienced pilots, we are, in a much smaller, but no less meaningful way, starting up that wonderful yellow inspiration machine. Today, in the form of vintage aircraft like the Tiger Moth, Finch, Cornell, Harvard, Chipmunk and Stearman, the beat goes on.

This summer, the Stearman made its way across the Rockies to Victoria in just one day. There, the pilots briefed hundreds of cadets on the core messages, the history of the RCAF, VWC and then it took 50 wide-eyed cadets in the air. Once that was accomplished, the old yellow biplane once again crossed the Rockies, heading east to Southern Alberta and the once active training air base known as RCAF Penhold, near Red Deer. In 1966 it became the home of the Penhold Air Cadet Summer Training Centre. Carrying on a tradition that dates back decades, PACSTC is home to the basic leadership, flight scholarship courses and Regional Air Cadet Bands.

During the summer PACSTC hosts some 800 Air, Army and Sea Cadets at a time (roughly 1250 cadets throughout the summer) who attend one of the many courses offered on base. These are taught by an additional 150 Staff Cadets who run the canteen, sports activities, security and training on base. There are also roughly 200 officers and Civilian Instructors who supervise all activities at the summer training centre. For some of the Yellow Wings pilots, this was home turf.

Penhold, Alberta, and No. 36 SFTS

A small town with a big role to play in Canadian History

During the Second World War, the small community of Penhold was host to a large and very active base of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. In 1940, the base opened as an RCAF Manning Depot with only one building. Five hangars and 31 other buildings (barracks, service and administrative structures) were still under construction well into 1941. Six hard surfaced runways ranging from 900 to 1,075 metres long made up the airfield. Two additional hangars were built for a total of seven. In August 1941, the base was handed over to the RAF and No. 36 Service Flying Training School was transferred from Britain, along with Airspeed Oxford aircraft. Relief fields were set up at Innisfail and Blackfalds.

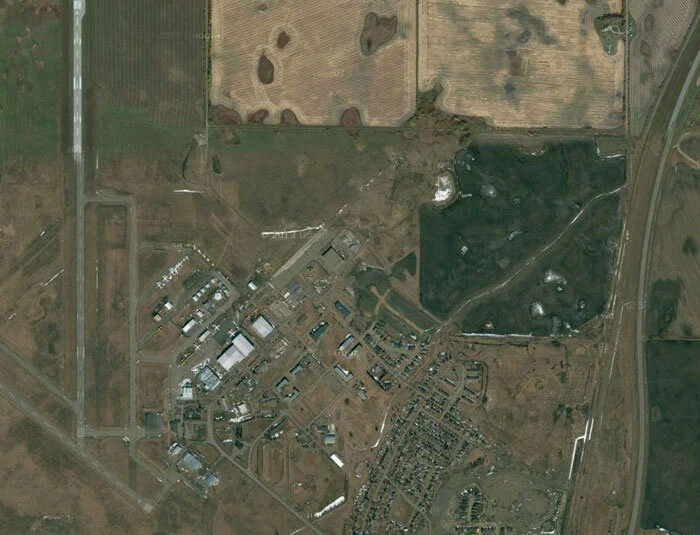

The Penhold airfield still functions today, more than most former BCATP bases in the West, but many of the hangars are now demolished or destroyed by fire and only 2 of the original six runways still accept aircraft. Image via Google Maps

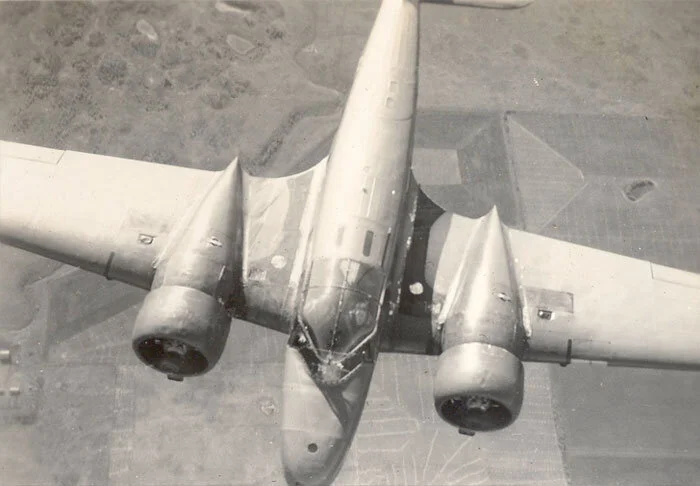

During the Second World War, the service flying students at No. 36 SFTS were instructed on the Airspeed Oxford twin-engined trainer. The Airspeed AS.10 Oxford was used for training British Commonwealth aircrews in navigation, radio-operating, bombing and gunnery during the Second World War. They were all built in Great Britain and were shipped to Canada for the use of RAF students. This and the following vintage photographs were taken by Royal Australian Air Force pilot F/O Ray Morgan in 1944. In this shot, Morgan, in the co-pilot’s seat, photographs another Oxford over the engine nacelle of his, with the Alberta prairie below. Photo: F/O Ray Morgan, via Nektonic at Flickr

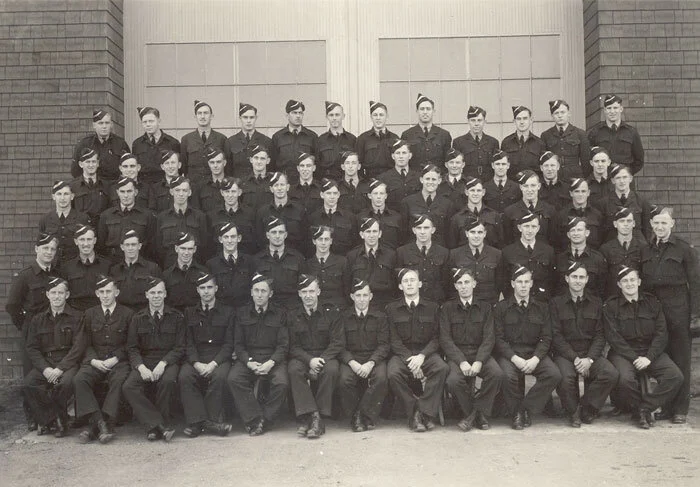

Thousands of students went through No. 36 SFTS at Penhold. Each course sat for their group photograph. Here we see the students (with white cap flashes) of Course No. 105 sitting for the station photographer in June 1944. Photo: F/O Ray Morgan, via Nektonic at Flickr

Out on the Alberta prairie in 1944, the flying was exceptional. Here we see a couple of young RAF or RAAF pilots from No. 36 SFTS inching their way up under another Airspeed Oxford. Photo: F/O Ray Morgan, via Nektonic at Flickr

Student pilots from No. 36 SFTS, Penhold, Alberta form up echelon left over the prairie. Here we see the exceptional visibility provided by the cockpit glazing of the Airspeed Oxford. Photo: F/O Ray Morgan, via Nektonic at Flickr

Training is always a dangerous game. Photo records such as those of Australian Ray Morgan show a breathtaking array of Oxford accidents at Penhold, but no more than any other flying training base. This Oxford crash at Penhold shows that the aircraft may have struck small trees. The resulting damage appears to be such that grievous injury or even the death of the pilot was the result. Photo: F/O Ray Morgan, via Nektonic at Flickr

Post war, Penhold became a major training base for RCAF pilots. After initial training on the de Havilland Chipmunk, fledging pilots would advance to the more challenging Harvard 4, before going on to the T-33 Silver Star to earn their wings. Here is a great photograph of the Penhold flight line in the early 1960s with scores of Harvards awaiting their students and instructors.

Messages from some inspired Young Canadians at Penhold

It is important to note that this is just one camp, one venue, one group of inspired pilots committed to the Yellow Wings mission to inspire the leaders of tomorrow. All across Canada—in Gimli, Trenton, North Bay, St. Jean, Debert, Greenwood and Gatineau—similar teams of Canada’s finest aviators deployed to other air cadet camps with other vintage aircraft. The result was the same—inspired and motivated young Canadians, safe and professional execution of the mission, inspired pilots and successful achievement of the goals our sponsors and donors are supporting us for. Today, as I speak, in Nova Scotia, the Eastern team is lifting off into the grey Maritime skies with 50 more talented, enthusiastic and very lucky cadets. But for now, let’s take a look at a typical cadet summer camp and the effect of the Yellow Wings program on 52 of its attendees.

Fertile young minds, eager for inspiration and direction. More than 700 Air, Navy and Army cadets listen intently in a Penhold hangar as Yellow Wings pilot Ron Dujohn, himself a former air cadet and now a Westjet Captain, briefs them on the Yellow Wings program and the mission of Vintage Wings of Canada. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Belted in and ready for flight—16-year-old Maria Higuerey, originally from Venezuela but now an air cadet in Fort McMurray, Alberta gives us the thumbs up before her flight back in time. Afterward, Higuerey had an even bigger smile, saying, “My experience with Vintage Wings was amazing and inspiring. I am really glad to have the opportunity to fly in one of the aircraft with such an interesting and amazing history. The best part of my experience was flying the aircraft myself. Being chosen was a privilege and I am truly happy to have been part of the ride. The Canadian Air Cadet Program sparked a personal passion for flying. After finishing High School and Cadets, I am planning to go to University to study aerospace engineering and I would also like to join the military. I thank Vintage Wings for making my summer the best summer I have ever had so far and also for giving me a memory that I will definitely preserve forever. I would also like to thank the Canadian Cadet program for giving me this and many other opportunities and making my dreams come true.” You’re welcome Corporal Higuerey! Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Cadet Taran Nasedkin and pilot Krusti Whelan share a moment of humour as “instructor” 16-year-old Taran jokingly berates his “student” Whelan for not knowing all the items on the Stearman checklist. All the cadets at Penhold were invited to pose for a unique post-flight photograph—and this one takes the cake. Nasedkin is a Sergeant at 577 “Dragonriders” Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron in Grande Prairie, Alberta. He was attending the Military Band – Advanced Musician Course at Penhold Cadet Summer Training Centre. Of his flight, Nasedkin said, “I was given the opportunity to participate in the Vintage Wings program and fly a Boeing Stearman, open-cockpit biplane. This was an incredible, once-in-a-lifetime experience. Being able to not only fly in, but to take control of and actually fly the plane was absolutely unreal. There is absolutely nothing like flying in an open-cockpit plane. I’ve flown in gliders and in Cessnas and this is a completely different experience. There are no words that can truly describe it. When I graduate high school, I plan on becoming a Paramedic. I would also like to obtain my private pilot’s licence. I would like to thank the Canadian Cadet Movement, Vintage Wings of Canada, and everyone else who made this incredible experience possible.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Yellow Wings pilot Derek Blatchford, himself a long time cadet instructor and tow pilot, shakes hands with his next passenger, 14-year-old Amanda Loeffen, a Flight Corporal at 38 “Anavets” Squadron in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. “I thank Vintage Wings and their generous sponsors and donors for reassuring me that flying is what I want to do with my life, I will remember that moment forever,” said Loeffen after her first flight in an open-cockpit aircraft. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Matthew Taylor, a 16-year-old Flight Sergeant at 702 “Lynx” Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan holds his boarding pass, confirming he is good to go aloft for a trip back in time over the Penhold gliding base near Red Deer. Matthew said, “The fact that I was chosen for such a unique opportunity was a great honour, and I hope that this once-in-a-lifetime chance will be available to many more Cadets in the future. Upon completion of high school, I want to go to university and eventually become an Aerospace Engineer with the Canadian Forces. I would like to thank all the generous sponsors and donors for the amazing opportunity they have provided. That thanks would be on behalf of all cadets who got to take part of the great opportunity.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Pilot Krusti Whelan and his “student” Gregory Esman pose with the Harry Hannah Stearman after their flight. Esman is currently a Flight Sergeant at 872 “Kiwanis Kanata” Air Cadet Squadron, and he had this to say about his experience: “My flight with Vintage Wings was absolutely fantastic. One of my favourite parts was actually flying the Stearman. That was an exciting, rare, and an extremely fun experience. The fact that I was even given the opportunity to fly in a Vintage Wings aircraft is a gift in itself, but actually being picked as one of the lucky cadets to fly in one is amazing. If I were to get the chance to meet one of the generous donors, I would definitely give them all my gratitude for their ongoing efforts to keeping this amazing program going.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Flight Sergeant Darcy Wong of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, a 16-year-old from 107 “Spitfire” Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron has some mighty grand plans for his future, and if he accomplishes even half of them, the world will indeed be a better place. “My experience from Vintage Wings is definitely one of the best things I’ve done in cadets, if not the best. When I was up in the air, it felt like a second home. The best part was everything from the takeoff to the landing, it was simply majestic. In five years, I plan to be finishing my mechanical engineering degree and going to achieve a degree in Business and Administration as well as going into commerce. After cadets, I plan to pursue my interest in business. After I have completely finished with school, I plan to invent a car that does not pollute and sell it worldwide, then moving onto other projects in infrastructure and other means of transportation. After that, I plan to completely revolutionize the energy industry into a 100% renewable grid and change the world. I would like to thank those who made this experience possible for me and to say please keep helping this program because the change starts small and it will only get bigger. This program is small in terms of a world scale but I have every belief that it will only get bigger.” 40 years from now, we would like to think that the world was saved by Darcy because of the inspirational spark we gave him. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Air cadet Barbara Young, a 17-year-old Flight Sergeant at 107 “Spitfire” Squadron in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan is reluctant to let go of the Stearman after her flight back in time over Penhold. Barbara tells us, “I was super excited when I heard that Vintage Wings was coming to Penhold. This was an amazing experience for me. I have always been interested in aircraft ever since I was little; aircraft and flying have been a passion of mine for a very long time now. I thank Vintage Wings and everyone who have made this opportunity amazing for me. This has honestly been one of the most wonderful experiences of my life... They have inspired me to do what I can do, always keeping your goals high, never doubting yourself and always keeping your head held high. You can only achieve what you put your mind to. I would like to thank Vintage Wings once again for everything and for making one of my dreams come true.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Young Kim Gosbjorn from Bon Accord, Alberta, a 15-year-old cadet from 524 “Sturgeon” RCACS poses straddling the cowlings of the Stearman in which he just went for a ride at Penhold summer camp. Kim tells us, “I am on a six-week Air Rifle Marksmanship Instructor course at Penhold Air Cadet Summer Training Centre and I am having an amazing time. I get to have lots of time on the range and all of the flight staff and other cadets are really awesome. Flying with Vintage Wings was easily the coolest thing I’ve ever done through Cadets. I know that it is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and I will remember it for the rest of my life. The best part was definitely when I was able to control the plane for a little bit. I hope to get my own pilot’s licence through cadets and in five years, I hope to be in university preparing to join the RCAF and becoming a pilot in the military. To all the sponsors and generous donors, you have given a lot of cadets a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and you have helped make dreams come true for a lot of cadets.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Logan Praznik, a third-year Air Cadet with the rank of Flight Corporal, from 82 “Brandon” RCACS, offers us and our sponsors a unique perspective on his experience: “If I was approached by one of Vintage Wings’ sponsors, I would tell them, ‘Aviation, in many ways, is the cutting edge of many fields in one final product. Thank you, not only for letting me see what the cutting edge was 70 years ago, but also how we’ve improved now, and where we might go in the future.’ ” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Sergeant Jessen Liang, 16 years old, from Calgary, Alberta, is from 604 “Moose” Squadron and was flown in the Stearman by Vintage Wings pilot Jeff Bell. Of his surprise flight in the Stearman, he had this to say, “Not knowing what to expect, we marched over to the airport to receive a small pre-flight briefing. Shortly thereafter, I was led by my pilot out onto the apron, where a Boeing Stearman Trainer was waiting for us. I was belted in, and after a bit, the radial engine was cranking and getting us into the air. We flew a circuit, air blasting through the open cockpit. The best feeling was that of the raw exhilaration from having a once-in-a-lifetime chance to have a flight in a piece of Canadian history. The experiences I have gained here are unforgettable, and will definitely help me in my career and education, both in Cadets and out. In 5 years, I will be in my third year of University, where I want to be studying Aviation Technology and Mechanical Engineering or other Technological-related courses. Cadets and especially the matchless opportunities that I have gotten from the program such as this one, will irrefutably help me in my future career. Thank you to Vintage Wings and their sponsors, Raytheon, for a great experience, a great program, and a great flight! The experience has definitely inspired a track for me to continue on into an Aviation-related career.” Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Wherever you go in life, if you are lucky, you will run into enthusiastic, creative, and driven people; people who go beyond what is asked and turn a simple job into a great job; people who don’t just give you what you ask for, but people who give you much more; people like Sergeant Tim Wun of the Penhold cadet staff. Tim organized much of the behind the scenes administration, creatively photographed each flying cadet, interviewed them and turned their responses into posts on our 500 Dream Take Wing Facebook site. He has enabled us to show the true benefit to Canadians of the Raytheon Canada Yellow Wings Youth Leadership Initiative. Now, if only we could clone Tim and take him across Canada. Photo: Fiona Stevensen

Throughout the flying day, Wun was always on hand to create a record of every flight, and every emotion expressed by the cadets who got to fly in the Stearman. Then, after the flying, Tim got to work processing the photos and collecting and editing the comments from the young girls and boys. Photo: Fiona Stevensen

Return to Netook

Upon the return flight to Calgary, it was decided to take the Harry Hannah Stearman a hundred kilometres north of Calgary to visit the base she once called home—No. 34 EFTS Bowden, Alberta. The site of the airfield at Bowden shows only faint traces of its original use. Back in the 1940s, Bowden was used by men seeking freedom in the skies. Today, the sight is the home of Bowden Institution—a medium-security prison facility. Men there still seek freedom!

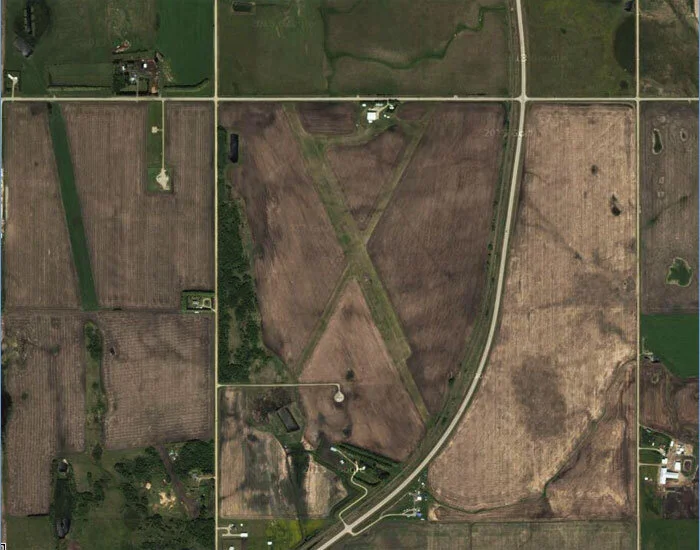

If the main base was not available for her homecoming, Netook, one of her satellite relief fields, is still in operation today both as an airport for the nearby town of Olds and as an air cadet gliding centre. The X-configured field of Netook is also the place where, in 1943, FJ875, the Harry Hannah Stearman, suffered considerable damage in a taxiing accident on the grass fields north of Calgary.

FJ875 touched down on the lush green grass of Netook 70 years after leaving it for the last time, roped to the bed of a farm truck. While there last week, the Stearman team set up a photo shoot to recreate a photograph that was taken at the time of a wingless FJ875 being prepped for transport back to Bowden. But first, a few historic images of Bowden and the days of Stearman operations.

A satellite view of Netook today. Netook, the municipal airport for the small Alberta farming community of Olds, is located 4 miles north of the town. The airport is owned and operated by the Air Cadet League of Canada – Alberta Provincial Committee. It is home to the Netook Gliding Centre, one of five Air Cadet Gliding Program locations in Alberta. During the Second World War, Netook was a Relief Landing Field for No. 32 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Bowden, outside Calgary. As such, it was designed to take aircraft practising circuits and forced landings and thereby relieve the traffic at Bowden on busy days. It features two intersecting grass strips of good length—Runway 01–19 (3,700 ft) and Runway 14–32 (4,400 ft). Image via Google Maps

A couple of women staff at No. 32 EFTS Bowden pose on the flight line with a line-up of immaculate Boeing PT-27 Stearmen “Kaydet” aircraft. When the 300 PT-27 trainers were returned to the USA over a period of many months, some of them, like FJ875 were re-engined and rebuilt to the PT-17 Standard of the USAAC. Photo via Clarence Simonsen

Another shot taken from a taxiing Stearman at Bowden shows a number of the beefy looking trainers awaiting their instructors and students. One can imagine the bright yellow aircraft, the green prairie grass and the cloudless blue sky. Photo via Clarence Simonsen

Another great photo on the flight line at Bowden shows both Stearman and de Havilland Tiger Moth aircraft awaiting students and instructors. It was on this flight line in these Stearmen that Archie Pennie learned to fly—so well in fact that he was made a flying instructor at Assiniboia, Saskatchewan. Photo via Clarence Simonsen

RAF flying students (the white cap flash indicates their un-winged status) pose with a Boeing Stearman on the flight line at No. 32 EFTS Bowden. Though the aircraft were eventually deemed inadequate for open-cockpit flying training in Canada, due entirely to their lack of cold weather capabilities, all the young RAF flyers who learned their initial flying skills on the big, beefy and yet nimble Stearman considered themselves to be part of an elite. Looking at the number on the underside of this Stearman’s wing, it appears like it could be FJ87_. The last number is obscured, but we could be looking at our aircraft! Photo via Clarence Simonsen

The Warrant Officer Harry Hannah Boeing PT-27 Stearman is in fact one of the original group of 300 Stearman aircraft acquired for the British Commonwealth Air Training plan and assigned specifically to elementary flying training of only RAF student pilots and only in Alberta. Today, she is in pristine condition, having been returned to Boeing in the United States after several months along with all 300 Stearmen BCATP aircraft, which were deemed inadequate for flight training in an Alberta winter. During its training career at No. 32 EFTS, our Stearman (RCAF s/n FJ875) was involved in a ground taxiing accident with another PT-27 Kaydet at Netook Relief Field, with both aircraft suffering serious damage to their wings. Here we see mechanics from Bowden, sent to bring back the damaged airframes, removing the upper port wing of FJ875 on the grass at Netook. Photo via Clarence Simonsen

After its accident at Netook, and with its wings and empennage removed, the Stearman’s tail was lifted and tied to the bed of a farm truck and towed back the few miles to Bowden. Here we see FJ875 with what appear to be locals (the man in the military style cap is not an officer in the RAF or RCAF—possibly the truck driver). Photo via Clarence Simonsen

Boeing Stearman FJ875, which is today the Warrant Officer Harry Hannah Stearman, is seen at Netook in 1943, shortly after it collided on the ground with another Stearman while taxiing on the grass. Riggers from Bowden arrived soon after and removed the wings and empennage from the damaged aircraft. While mechanics work at the tail, one, in aviator sunglasses, relaxes in the cockpit, perhaps toeing the brakes and poses for the RAF photographer sent out to take photographs of the incident’s aftermath. It was this photograph that the Stearman pilots and the Netook cadets of today would recreate when the Yellow Wings team paid a visit last week. Photo via Clarence Simonsen

Cadet gliding instructor Emily McConnell re-enacts the scene at Netook 70 years ago. The only differences are that we kept the wings and empennage on the aircraft and, more importantly, there are women pilots and mechanics in the air force. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Cadet Officer Becca Howard plays the part of the young Bowden rigger who sat in FJ875, 70 years ago. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Just the day before, glider flight instructor Emily McConnell was taking the controls of the Harry Hannah Stearman in Penhold with Krusti Whelan as pilot in command. Today, the roles were reversed, and Emily got a chance to return the favour, taking Whelan aloft for some quiet time over the Netook glider field. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team

Back in the barn for a little down time, the Harry Hannah Boeing Stearman has done yeoman service at flying through the Rockies to Victoria on Vancouver Island and then back again to Red Deer and the former BCATP base at Penhold. Photo: Yellow Wings Stearman Team