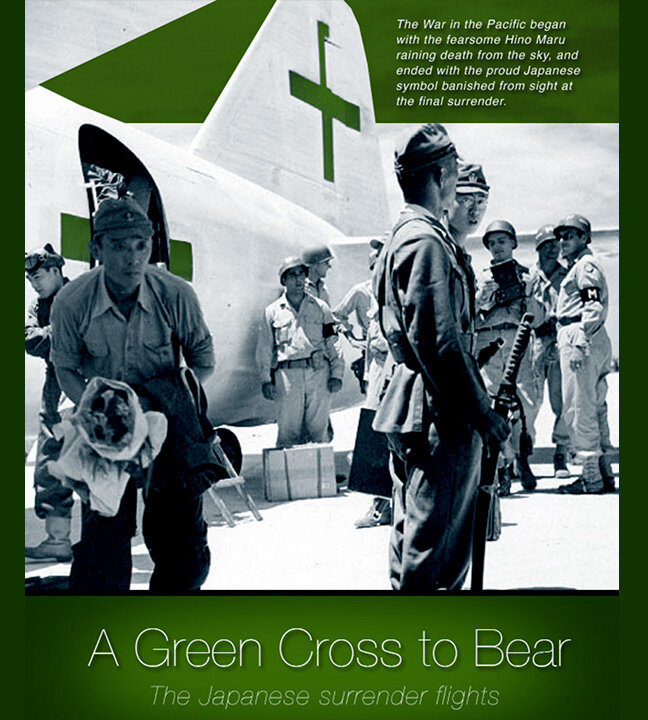

THE INN OF THE DIVINE WIND

Forward by Dave O’Malley

As early as the summer of 1944, Japanese Army and Navy fighter and bomber pilots began training for “special attack” suicide missions against both Allied ships and aircraft. Known as kamikazes (from the Japanese words for Divine Wind), these young men would volunteer and gather in special attack squadrons at Japanese Imperial Navy and Army air bases where they would receive final training and prepare for a mass attack.

Japanese to English translator, Nick Voge of Hawaii, himself a commercial pilot, has selected three vignettes from the memoirs of Reiko Akabane, narrated by Hiroshi Ishii, to shed light on the humanity and tragic last days of the kamikaze. Reiko Akabane was the young daughter of a Japanese restaurant and innkeeper by the name of Tome Torihama. Tome’s inn and restaurant, called the Tomiya Inn, near the Japanese Imperial Army airfield at Chiran on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu were frequented by kamikaze pilots training at Chiran as well as by their families who came to visit them before their one-way flights. Tome became something of a surrogate mother and confidant to many of these young men during their final days.

The book, entitled Hotaru Kaeru (in English Firefly Return) by Akabane and Ishii was published in 2001 in Japanese. It tells the story of Reiko Akabane and her mother Tome Torihama and their real life interactions with these tragic but beautiful men and their families. The title comes from one of the vignettes as told by Akabane. One pilot tells her mother that when he dies, he will return to her inn as a firefly. On the evening of his death the garden at the inn was visited by one particularly bright firefly, which Tome took to be the reincarnated pilot.

Here now are the three short vignettes, for the first time translated from the Japanese by Voge, which may, in a small and gentle way, teach us who these men were. Despite what you may feel about the sins of the Japanese in China, Korea, and the Far East prior to and during the Second World War (and there were many), these men were young, courageous and doing what they truly believed would, in the end, save their country. They did not come from a martial background, but were mostly schoolboys and young working citizens. They were not terrorists, but uniformed soldiers and sailors attacking uniformed enemy combatants in a one-way mission. Think what you may, but they do deserve our respect.

The Tomiya Inn, Tome Torihama’s small hotel and restaurant exists to this day, though it is now a memorial and museum to the events that took place there nearly 75 years ago. It is curated by Tome’s grandson. Photo: Wikipedia

Lieutenant Wataru Kawasaki — Love and Death

I don’t remember exactly when Lieutenant Wataru Kawasaki arrived at Chiran, but it was probably around the end of April [1945]. He was in the same aerobatics class with Lieutenant Hikaruyama and both were in the 51st Shinbu Unit. Lieutenant Kawasaki was from Hayato in Kagoshima Prefecture, and since he spoke the Kagoshima dialect he was a big favorite at Tomiya’s. Mother and I could speak candidly with him, so we often joked around and soon became close friends. The local dialect has many subtle nuances that are difficult to communicate to outsiders. When speaking standard Japanese, a formality inevitably arises that prevents the kind of spoken intimacy fostered by a shared dialect. It was probably this, more than anything, which led him to entrust his secrets to my mother. She became his confidant, and I often saw the two of them deep in conversation.

It seems that after graduating college, Lieutenant Kawasaki had moved to Nakano, in Tokyo, where he became a primary school teacher. It was most unusual for a man like him to become a pilot. At twenty-eight, he was already much older than the other pilots and as a result occupied a special position among them. He confided to my mother that he was engaged and that he was deeply concerned about what would become of his fiancée.

One day, a young woman appeared at the door of our inn. My mother was shocked at how emaciated she looked. She was wearing old pantaloons and seemed somewhat dirty. She said she had come from Tokyo to visit Lieutenant Kawasaki. That explained her disheveled appearance. With the war entering its final stage, the few trains still running were seldom on time and tickets were almost impossible to come by. Coming down from Tokyo on the Tokkaido Line, changing to the Sanyo Line and then to the Kagoshima Line must have been an exhausting ordeal. She must have been travelling for days.

Without even asking her name my mother knew that she was Lieutenant Kawasaki’s fiancée.

“You poor thing. Please come in,” were her only words, as she showed the girl to one of the upstairs rooms.

“I’ll bring you some tea in just a moment. After you’ve had a little rest, the bath will be ready. Lieutenant Kawasaki is sure to stop by later, but if he sees you looking such a mess he’ll be even more worried. It’s not good to make someone who loves you worry.”

So saying, my mom hurried back down the stairs and soon returned carrying a pot of freshly brewed tea.

“Now then, here’s some tea. The bath is ready, too. There’s a washcloth and shampoo there. So wash your hair and come out looking beautiful.” Mom sounded like a general giving orders.

When the girl came out of the bath her dirty clothes were already cleared away, replaced by a neatly folded lady’s kimono. My mom had her sit in front of the mirror and helped her comb her long hair and apply some light makeup. When all was finished the girl again looked like a beautiful young lady. My mom thought she was gorgeous.

“That will do just fine,” she said with a satisfied smile. “Now, Lieutenant Kawasaki can come by any time.”

Gazing at her transformed self in the mirror, she must have wondered why this nice lady who had never seen her before was being so kind to her. Had she asked, my mom would probably have said: “It’s only proper. After all, you’re going to meet a god.”

Her name was Ayako Fuse. In the tenderness of my mother’s care she soon lost her inhibitions and spoke freely of herself. She told of how Lieutenant Kawasaki and she were teachers at the same primary school in Nakano, and how they had fallen in love. She spoke of her shock on hearing his intention to become a pilot, and of the devastation she experienced upon learning that his application to the Special Attack Corps was accepted. Hardly bothering to pack, and thinking only of seeing him before his final mission, she boarded the train and rushed down to Chiran as fast as she could.

Related Stories

Click on image

Innkeeper Tome Torihama poses with a group of young kamikaze pilots at the front door of her inn in the town of Chiran. In this photograph, she looks happy and relaxed, but she knew it was her job to never show sadness or fear in front of the young boys and men who were soon to go to their deaths. When we look at this image it is hard to see through their charm and boyish delight to the underlying desperation they all must have felt. Photo: WarbirdForum.com

It was easy to imagine the heartache my mother felt upon hearing the story of their love. And when Ayako expressed her desire to marry Lieutenant Kawasaki before his mission, she could find no words to express her emotions.

“We promised each other that we would be together for all time. Even if he should die now for our country, I want to spend the rest of my life as his wife. Then, when I go to the next world I can spend all eternity with him and have a clear conscience.”

This heroic resignation moved my mother profoundly. How, she wondered, could such powerful words come from such a delicate young lady?

“You want to take your wedding vows even though you know he will die?”

“Yes.” Ayako looked down as she said this.

“Lieutenant Kawasaki’s parents will never permit it.”

Ayako’s eyes filled with tears, but there was a fierce determination in her voice.

“If his parents forbid us to marry then I would rather kill myself before he leaves on his attack. Then I would have no regrets.”

Mother was speechless. She knew that if Ayako felt that strongly about it that it would be best for them to marry. But she also knew that society would never condone a marriage to a man facing certain death.

Lieutenant Kawasaki’s parents arrived at Tomiya’s from the town of Hayato not long after Ayako. A letter had informed them of his imminent attack. He was their oldest son and they had come to say goodbye to him. As soon as my mother learned that this older couple were Lieutenant Kawasaki’s parents she quickly decided to give them a room as far away from Ayako’s as possible. She was worried about what might happen if the two parties should meet. No sooner had they introduced themselves that they were confiding freely in my mother. My mom was very outgoing and their open conversation was facilitated by the local dialect they shared. Learning of their son’s final mission, they had come to Chiran to bid him farewell in the hope of easing his mind.

Lieutenant Kawasaki showed up that evening. Mother took him aside and whispered: “Your parents are here. Ayako, too.”

“What? Ayako came?”

“Don’t worry, I saw to it that they didn’t meet.”

“Thank you so much. Every day I fall more deeply in your debt.”

Lieutenant Kawasaki thought for a few moments. Deciding to see Ayako first, he silently went upstairs. Joyful though their meeting must have been, within ten minutes he came downstairs.

“Miss Tome. We’ve decided to go ahead.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Ayako is determined to marry me. Even though she knows that I’ve got only two or three days left to live, she wants to say goodbye to me as my wife. My parents are firmly opposed but I must try to win them over.”

“Well, good luck.”

My mom brought Lieutenant Kawasaki to his parents’ room and spoke to them through the sliding door.

“Your son is here.”

Lieutenant Kawasaki slid the door open. Kneeling in the hallway dressed in his flight suit he placed his hands on the floor before him and prostrated himself as he greeted his parents. When Mother saw that he had entered the room she slid the door closed behind him and returned to her room.

My mother felt terrible for Ayako. In these situations it is usually the girl’s parents who hesitate to give permission to an ardent suitor. But in this case the groom-to-be was facing imminent death and the girl would very soon be a widow. Her life would be over.

Still more, Lieutenant Kawasaki was a kamikaze pilot. In spite of this Ayako wanted to marry him. Even if it were only once, she wanted to be called his wife.

“I want to part with you as your wife,” she had told him.

After about thirty minutes Lieutenant Kawasaki returned to my mother’s room. His face was pale.

“How’d it go?”

“They wouldn’t hear of it. Impossible.” He bit his lip as he said this.

“I couldn’t even explain. They just said: ‘This is no time to talk about a woman. We came today to see you off on your attack. Besides, you can’t simply turn a young girl like that into a widow.’ We couldn’t even talk about it. Ayako is so determined, now I don’t know what to do.” Tears filled his eyes.

“What are you going to tell Ayako?”

“I’ll tell her I’ll talk to my parents again tomorrow.”

“I wonder if she’ll accept that.”

Lieutenant Kawasaki stared mutely at the ceiling, unable to speak.

“Why don’t you spend the night here with Ayako?”

“No, I’ll go back to the barracks.”

I don’t think any of them got much sleep that night, my mom included. She understood everyone’s feelings all too well. As she thought of the courage of the young lovers and their plight her pillow was soon wet with tears. Unable to sleep, she wracked her brains trying to think of some way to satisfy the desires of the young lovers and win a concession from the parents. Mother was terrified lest Ayako, her dream of marriage frustrated, kill herself. Then, two lives would be lost. That one of them had to die couldn’t be helped, but if both should die it would be a tragedy.

At 28 years old, Wataru Kawasaki was much older than most kamikaze or Special Attack pilots. This photo shows us just how young they were. The image shows five pilots of the 72nd Shinbu Squadron at Bansei, Kagoshima, formed on 30 January 1945. They are (left to right) in front row: Tsutomu Hayakawa (19), Yukio Araki (17), Takamasa Senda (19) and back row: Kaname Takahashi (18) and Mitsuyoshi Takahashi (17). All five died the following day (9 May 1945) attacking Allied ships off the coast of Okinawa. Photo: Wikipedia

Even if no concession could be wrung from the parents, Ayako had to be convinced to live. She couldn’t be allowed to take her own life. And yet, however persuasive my mother’s entreaties, they would sound hollow and trivial to Ayako. What to do? When dawn arrived my mom was still struggling to find an answer.

That morning Lieutenant Kawasaki arrived early at Tomiya’s. It was his last day. He went first to visit Ayako, then, after a while, to his parents. But nothing had changed. Before long my mom was also talking with them. But when all was said and done, they were right back where they started. Neither Lieutenant Kawasaki nor Mother could think of how to convince Ayako to continue living. Lieutenant Kawasaki said goodbye to Ayako and returned early to his barracks. That was their final goodbye.

The next day, 11 May, was the big attack. Many other young men we had come to know at Tomiya’s also took part. More than thirty pilots, including Lieutenant Kawasaki, took off from Chiran. As usual, Mother and Older Sister and I rose early that morning and went to the airfield to see the pilots off. As I recall, Lieutenant Kawasaki’s parents went with us, but my mom persuaded Ayako to stay in her room. As the planes roared off into the dawn sky and the drone of their engines dwindled to distant thunder, Ayako said a final farewell to the man who in her heart, would always be her husband.

She left for Tokyo that afternoon.

But Lieutenant Kawasaki didn’t die after all. He returned to Tomiya’s once again. This time, though, his face was clouded with anger, his expression hard. Even if engine trouble forced a pilot to return, those “left alive” were treated coldly. His own emotions seemed confused as well. It was a dishonor to be the only one left alive when all your fellow pilots were dead. There were no more jokes from him in the local dialect. And when he did show up to eat at Tomiya’s he did so in silence. My mom understood his feelings well, and although she prepared his favorite dishes there was no softening in his attitude.

Finally, on 28 May, his plane repaired, he left on another attack. But this time, too, engine trouble forced a return.

“Looks like Kawasaki can’t bear to be without his girlfriend,” was the cruel rumor making the rounds. It may have even made it as far as distant Hayato where, had they heard, Lieutenant Kawasaki’s parents would be deeply hurt.

It did in fact seem as though his lover’s refusal to acknowledge his death was keeping him alive. A more prosaic reason was, however, that many of the planes sent to the special attack units were barely airworthy. The military was keeping the best aircraft in reserve for defense of the main islands—those used for kamikaze attacks were expendable. Most were planes that were outdated on the front lines, so it was no surprise that they suffered frequent mechanical problems. Many planes were forced to ditch in the ocean or to make forced landings on other islands before they ever reached Okinawa. In fact, there was nothing unusual about planes returning from a mission.

A look at the statistics reveals that only forty-nine of the planes that sortied from Chiran were the modern aircraft.

25 October 1944: kamikaze pilot in a Mitsubishi Zero A6M5 Model 52 crash dives on escort carrier USS White Plains (CVE-66). The aircraft missed the flight deck and impacted the water just off the port quarter of the ship. Photo: US Navy, via Wikipedia

One day, Lieutenant Kawasaki appeared at Tomiya’s in rare good humor. “This time everything will go fine,” he told my mom. Whether the mechanics had assured him that all the problems were repaired or whether new parts had arrived for the plane I don’t know, but he was very happy that his plane was finally ready to fly.

“Just to make sure, I’ve received permission to make a short test flight tomorrow. If everything goes well I’ll sortie the next day,” he told my mom. “Thanks so much for taking such good care of me. I’m really sorry I hung around so long and caused you so much trouble.”

He did, however, have one final request. He entrusted two letters to my mom, one to Ayako and one to his mother.

“I asked my mom to help out Ayako. She understands the things that only a woman can. If she needs your advice, please help her if you can. Although she only stayed here a short while, she said that you treated her better than her own mother. For that she was deeply grateful.” Then he bid my mother farewell.

“Miss Tome, thank you so much for everything. It pains me that I can do nothing to repay your kindness. All I have done is to cause you trouble without doing anything for you in return. I promise to repay you when we meet again in heaven.” So saying, he waved goodbye and walked back to his barracks in the early evening light.

Waving farewell to him, my mother looked at the two letters. They were closed, but not sealed, and my mother took this as a sign that she could read them.

The next day, 30 May, Lieutenant Kawasaki took off on his test flight. His destination was his hometown of Hayato, some sixty kilometres distant. He flew low over the town, waggling the plane’s wings in a sign of farewell to his parents. The accident occurred seconds later.

His plane clipped a power line and plunged into a rice paddy, killing him instantly. Two farmers working in the field were also killed.

Mother cried when she heard the news. The final days of Lieutenant Kawasaki’s life had been cursed with misfortune. No reconciliation was made between his fiancée and his parents; he sortied, only to be forced to return repeatedly by mechanical failure; he was accused of being a coward and a weakling; and when he finally got the chance to redeem himself in an airworthy plane, he crashed and died during a test flight.

My mother must have known how galling this final humiliation would have been. All he left in the world was Ayako, and he entrusted her well being to his mother.

Following Lieutenant Kawasaki’s tragic death my mom wrote occasional letters to Ayako, and a correspondence developed between them. After the war ended it seemed that Ayako slowly began to recover her emotional balance, much to my mom’s relief. However, in spite of their son’s request, the Kawasaki family never acknowledged her as their son’s wife. Although she repeatedly wrote them, as Lieutenant Kawasaki had requested in his final words, none of her letters were ever answered.

Following is one of the letters Ayako wrote to my mom.

Dear Miss Tome, May 23

How are things? Thank you for your last letter, it cheered me greatly. I’m so happy to hear that you are well. Last year around this time was hard for us all. This month is especially difficult. In one more week it will have been exactly one year. That probably explains why every day recently I’ve been recalling the happy times Wataru and I spent together. How are things in Chiran these days? It’s pretty bad here in Tokyo; I don’t know how I’m going to manage. If only Chiran weren’t so far away I would love to see you again. Although I have written two or three letters to the Kawasaki family, they never responded, so I have stopped writing. I still watch over Wataru’s spirit, but I try not to think about his family, because it only makes me sad.

Please give my regards to everyone at the inn. Without the pilots around it must be very peaceful there. Please take good care of yourself. When times get better I promise to pay you a visit. Let us both take care of ourselves. Please give my best to your family.

Please excuse my sloppy writing and poor penmanship.

Yours, Ayako Fuse

As her letter stated, the Kawasaki family refused all contact with her—their son’s final wishes had been in vain. She wrote in a sophisticated, classical style that clearly revealed her educational background.

The years passed. And the day came when Ayako finally decided that it was time to stop living a life of solitude.

Dear Miss Tome, January 30

I hope this finds you enjoying the winter weather. How have you been? Please take care of yourself in the cold. Still, it must be warmer where you are, in the far south. How is everyone? Although four years have passed—four years of food shortages, of hot summers and bitterly cold winters—my thoughts are often in Chiran and probably will be for the rest of my life. There has been no communication between me and the Kawasaki family, so rather than spend the rest of my life living in the past, I’ve decided to start looking towards the future. I will soon be starting a new life. Please continue to advise me as you have done so well in the past. Although there may be times when I won’t be able to write for a while, don’t ever think that I have forgotten you. If you think of me at all, please imagine me facing the south and sending my prayers to you all.

Sincerely Yours, Ayako Fuse

Four and a half years after the war ended Ayako decided to “remarry.” For my mom, too, this chapter in her life had come to a close, and she could rest easy knowing that Ayako would be all right.

Lieutenant Ryöji Uehara — I’ll be dead soon anyway.

Lieutenant Ryöji Uehara came from the economics department of Keiö University and was a second-term aerobatics cadet.

He had the alarming habit of loudly saying, “Japan’s gonna lose,” regardless of who might be around. This greatly upset my mom, because the dreaded kempei (military police) were always watching Tomiya’s. When friends cautioned him he would simply say, “Who cares? I’ll be dead soon anyway. They won’t mess with me.”

Even so, going around yelling, Japan’s gonna lose! could cause problems. This was because most of the pilots who came to Tomiya’s truly believed they were sacrificing their lives to save their country. To the questions of why they had to die and why they were sacrificing themselves, the answer was simple: to save Japan. But if their death couldn’t help the country, it was a just a dog’s death and meant their lives were wasted. None of them wanted to think their death had no meaning. Most had to believe that a day would come when their supreme sacrifices would be vindicated, otherwise they could never have resigned themselves to death. So, when Lieutenant Uehara vented his beliefs, my mom’s chief concern was for the psychological effect it had on the other pilots.

In addition to his will, Lieutenant Uehara also left a long essay, in both of which he discussed his theory on Japan losing the war.

Although authoritarian or totalitarian states may experience brief prosperity, they must inevitably collapse. That truth is evident in what we see happening to the axis powers in this world war. Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany have already collapsed. One after another, like buildings whose foundation stones are crumbling, the totalitarian states are falling into ruin.

Since Japan was also a totalitarian state, he reasoned, it followed that it too would sooner or later meet the same fate. He was convinced that, in his words, “History will prove the eternal greatness of freedom. And though this may be disastrous for our country now, it will be wonderful for the Japanese people.”

In the Japan of the nineteen-forties, those ideas were far ahead of their time. To the authorities they were considered ‘dangerous thoughts.’ Anyone voicing such thoughts would immediately be arrested by the Special Secret Service Police or by the Military Police and could expect to be tortured.

Another favorite saying of his was:

While the fate of a nation is important, in the grand scheme of things it is of little significance. Even if America and England win this war, their nations too will one day collapse.

This prophecy, lucid though it was, reflected the Eastern philosophy that good fortune is inevitably followed by bad.

Of course, in Japan at that time there were others who shared similar thoughts, but they kept their mouths shut. They certainly weren’t the kind of people who became pilots and asked to join the special attack corps. And that was what made Lieutenant Uehara unique. According to his analysis of the kamikaze:

Thinking reasonably, the actions of the special attack pilots are incomprehensible. It is nothing more than suicide and, to the Western mind, simply inconceivable. Only in an emotionally charged country like Japan is something like this possible.

In seeking to justify such a death, he said that Japan’s view of life and death always gives greater weight to the value of death, and that nothing is worse than an obscure death. Because he believed that it would lead him to heaven, he felt no need to justify his death with long-winded explanations. He was unsettlingly articulate about it all.

While Lieutenant Uehara’s will and his thoughts were filled with these strong and principled statements, only a few sentences revealed why Ryöji Uehara, an economics major from Keiö University, had volunteered for the special attack corps.

When I step out of the airplane I’m like any other human being, swayed by the same feelings and passions. When my lover died, my spirit died with her. She’s waiting for me in heaven. When I think of her up there waiting for me, death is nothing more than a way for me to be with her.

The final words in his essay were:

Tomorrow a lover of freedom will leave this world. He appears lonely but in his heart exults.

Lieutenant Ryöji Uehara belonged to the 56th Shinbu Unit. He sortied on 11 May in a Type 3 Hien and never returned.

25 May had been designated as a mass attack day. On this day alone seventy-one aircraft sortied from Chiran. For those seeing the pilots off it was difficult to determine who was in which airplane and to tell the various aircraft apart. As soon as it started to get light, the lined up planes would all rev up their engines to a mighty roar. Then, all at once, they would take off, the sound of their engines reverberating like thunder. Once airborne they would form up into flights and head north of the airfield. Then they would wheel about and head for the fighter command building at the south end of the field. Trading altitude for speed, they would swoop low over the building, pulling up and dipping their wings as they roared overhead—a last goodbye before disappearing into the southern sky. They flew in the direction of Mt. Kaibun, a peak that shared its beautiful outline with Mt. Fuji. Located at the southern tip of Kyüshü, it was the last reminder of their homeland the pilots would see.

As the planes thundered down the runway Tome and the others waved them off with gusto. And although these farewells had become an almost daily occurrence, Tome found them unbearably sad—as though the planes, as they left the ground, were ripping her heart from her body. But at the airfield, and especially when seeing the pilots off, crying was strictly forbidden. Weeping on the inside, they gritted their teeth and forced smiles to their faces.

After drinking the ceremonial farewell cups of water the pilots would scatter to their aircraft. Those among them who noticed her would say something like, Sayonara, Tome-san! However, she could never make a proper reply. At most, she would say in a weak voice, “Take care.” She could hardly imagine saying, “Please take care, until you find an enemy aircraft carrier to crash into.”

One after another the planes leapt into the sky, Tome and the others waved to each one. Suddenly, from one of the planes a red paper streamer began to flutter. Like the other planes it climbed off to the north, then changed direction and came back on a southerly heading. Then it happened. Standing at Tome’s side, Lieutenant Nanbu’s mother suddenly opened her white parasol, held it above her head and waved it back and forth. Tome was taken aback. Lieutenant Nanbu and his mother had worked out this signal in advance so she would know which plane he was in.

A cameraman wearing a media armband snapped a photo of the plane trailing its red tail against the blue background of the sky. Dropping lower and lower the plane swooped down on the fighter command building and the small group of spectators. Just as the plane seemed about to crash into the building it pulled up in a steep climb, waggling its wings. As though in response to the frantically waving parasol, the red tape parted from the plane as it climbed away to the south in the direction of Mt. Kaibun.

As her only son flew off to a certain death she continued waving her parasol until the plane disappeared into the distance. The red tape, tossed about in the breeze, fluttered lightly down, settling on the ground with the gentleness of an apology. Thus, did Lieutenant Nanbu and his mother say their final goodbye.

When the plane was no longer visible, Lieutenant Nanbu’s mother slowly folded the parasol. Her downcast face was whiter and, thought Tome, even more beautiful in sorrow.

“Thank you for helping us see our son off,” she said with a bow. Tome could say nothing and bowed her head in silence. There were no words for moments such as these.

Meanwhile, other planes continued to depart, and the airfield reverberated with the roar of mighty engines that drowned out the sobs of those few who dared to weep.

Tome and the others continued waving until the last flights had vanished from the sky. When it was all over they were suddenly overcome with fatigue. A profound sense of emptiness overwhelmed them. Seventy-one precious lives had just departed on a mission from which they would never return. Nodding silently to each other, Tome and her daughters and Lieutenant Nanbu’s parents began the long walk back to town. As they left the airfield, they started on the downhill road to Chiran. This was usually the point at which Tome and her daughters started crying. Thinking of those who would never return made the tears impossible to stop. But today they held their tears, for with them were two whose loss was so much greater than theirs. Quietly, the five figures made their way down the hill and into town.

The next day the parents paid a visit to Tomiya’s to say goodbye. The mother was wearing very plain pantaloons in the so-called national defense colour. How fitting, thought Tome. Yesterday she had worn brilliant white and carried a white parasol to look her best for her son. Or, perhaps because her son was unable to wear the customary white costume worn on one’s final journey, she decided to wear white for him.

Bidding Tome a polite goodbye this quiet couple departed.

One year later, in May of 1946, Lieutenant Nanbu’s parents again appeared at Tomiya’s. In spite of the postwar inflation and terrible food shortages they had somehow managed to find a few kilograms of sweet fermented soybeans that they carried with them.

“This was his favorite food,” said the mother. “He could eat a bowl of this at one sitting. Since this is the anniversary of his death, we plan to cast it out on the ocean over which he fell.”

The broken heart of a mother who had lost her son was pitiful to see. Tome cried hidden tears for her. She thought of how parents count the years of their children’s lives and knew that Lieutenant Nanbu’s mother would spend the rest of her life counting the ages to which her only son had never lived.

On May of the following year and again the year after, the parents visited Tome at Tomiya’s. Each time they carried with them a heavy package of sweet fermented soybeans as they made their pilgrimage to Okinawa. It was a pilgrimage they were to make every year.

Some fifty years later, when memories of the war were fading into obscurity, an old man claiming to be a former special attack pilot appeared at the door of a certain family whose son had fallen over Okinawa. He was now, of course, a very old man and walked with crutches, but he claimed to have taken part in the same attack as the family’s son. The parents of the deceased pilot had by this time joined their son, whose younger brother was now living in the house. The old man claimed to be a comrade in arms of the fallen pilot and said he had come to pay his respects at his friend’s grave. When asked his name, he said it was Lieutenant Yoshio Nanbu. The brother of the dead pilot was astonished. “You survived!”

According to the old man’s story he never reached the enemy ships but crash landed in the sea nearby. When he came to he found himself prisoner in an American military field hospital receiving treatment.

The man’s brother asked the old man to wait a moment while he went into the next room to make preparations to accompany him to the family grave. But when he returned, the old man had vanished.

This story soon found its way to the few special attack pilots from the same squadron who were still alive, and they began to search for Lieutenant Nanbu. Rumor had it that he was living in Okinawa. Some of the men travelled there and visited a number of villages, but no signs of either a Yoshio Nanbu or a Yoshio Ishimaru (his stepfather’s name) could be found.

Some of the former pilots thought the old man was a ghost. Others felt that even if Lieutenant Nanbu had survived he must have lived a guilt-ridden and tormented life. Among the special attack pilots, survival was the most heinous crime of all. Continuing to live while your comrades died was considered the worst form of treachery. It was this that made the lives of the surviving pilots such a torment. Worse still to have been saved and cared for by the enemy. This in defiance of the military admonition drilled into every soldier: Never suffer the shame of capture. To the soldiers of that era nothing was more detestable.

If Lieutenant Nanbu was in fact alive, tormented by a guilty conscience, his fellow survivors wanted to help him. However, they were never able to find him.

Even after so many years, it sometimes seems as if the war is not yet over.

By Reiko Akabane

Cast members of the 2001 Japanese feature film Hotaru (Firefly) pose in front of a Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa. Japanese actors played the parts of pilots and in the centre, innkeeper Tome Torihama. Photo: SirringConstantly.wordpress.com

A haunting mural at the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots shows six angelic female phantoms lifting the body of a kamikaze pilot from his burning aircraft to take him to heaven. Photo: stripes.com

Aviator and a passionate translator of rare aviation-related Japanese works, Nick Voge poses with an L-19 Bird Dog at Dillingham Airfield, the former Second World War training field on the North Shore of Oahu. He flashes us the Hawaiian “shaka” sign, offering us the “hang loose” interpretation of the “Aloha Spirit.” Photo via Nick Voge