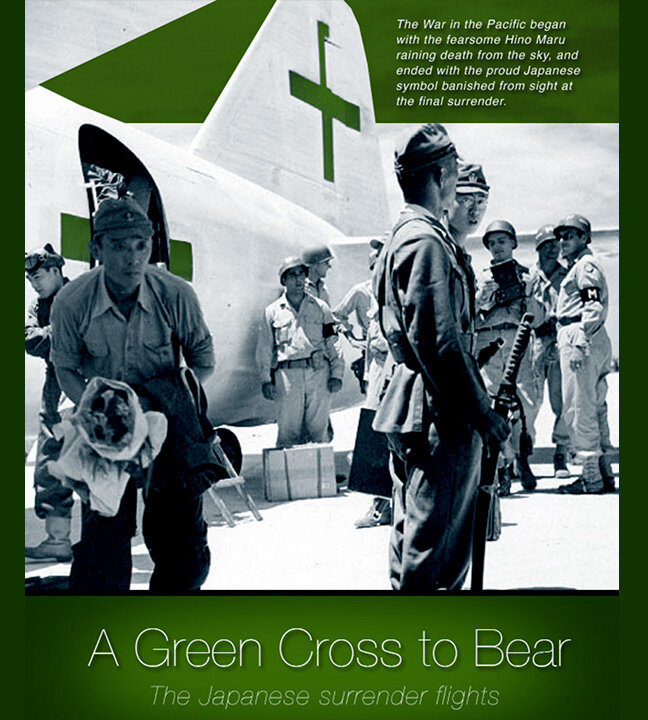

GREEN CROSS TO BEAR

There is a story told on the sides of every aircraft of the Second World War. It’s there in visual code written in worn and tired war paint, easily interpreted by those who speak this language of history. Always the story told is proud and warrior-like, a story of both present battles and of the sweep of history back to and even beyond the beginning of flight.

The opening lines of the story are told by the camouflage, the overall coat of paint donned by the fighter or bomber or transport. We read in an all-powder blue Spitfire that it is unarmed, that its pilot flies alone and unafraid, that it flies higher than the rest, taking photographs and evidence of movement behind enemy lines. In a P-40 Kittyhawk with brown and tan fields of colour, we read the heat, the sand, the deprivation and the vast sweep of the North African campaign. From the jungles of Burma, to foggy coasts of Iceland to the sun-blasted coral airstrips of the South Pacific, an aircraft carries the story of its battles in its paint. And on the side and wings of all aircraft, on all sides of the battle, were the most proud marking of all—the national roundels and symbols—historic markings that take their meaning from historic events and dynasties predating aviation—the crosses, roundels, cockades, hinomarus and stars of nations engaged in warfare for centuries and even eons. To one side they are anathema, symbols of abject evil, treachery and or even of a nation of subhumans. To the other they are glorious marques of courage, honour, duty and historic importance. Allied pilots and gunners learned not just to read the black Balkenkreuzes, bent Hakkenkreuzes, and red “meatball” Hinomarus of the Axis, but to hate them and to react instantly to destroy them.

On the flanks of Commonwealth aircraft of the Second World War, the visual language was even more complex, the story more telling. On their flanks there was generally an alphabetical or alphanumeric code which told a more granular story. A two-letter code forward of the roundel, known as the Squadron Code, told the initiated what specific squadron the aircraft and its pilot were attached to. This meant that a bomber pilot, whose radio was out and aircraft damaged could identify an aircraft of his squadron and be guided home. It meant that squadrons could form up in radio silence according to battle plans briefed earlier. Aft of the roundel there was more often than not a single letter—the Aircraft Code, identifying that particular aircraft within the squadron—A-Able, B-Baker, J-Jig, O-Oboe etc. To the pilots witnessing the destruction of a squadron mate in the heat of battle, the Aircraft Code might be the only way to tell who it was.

Personal stories were written all over the aircraft sides—an American Navy ace paints Imperial Japanese flags below his cockpit rail, one for every victory. A bomber crew points to the 50 missions their bomber has endured—one bomb silhouette for each lined up in rows on the cheeks of their tired old warhorse. One knew the home of a fighter pilot or a bomber crew chief by the nose art his aircraft wore—Oklahoma Miss, Arkansas Traveller, The Maine-iacs, Big Noise from Kentucky or the Belle of San Joaquin. One could also tell something of the pilot’s love life in the language of nose art. Pilots not spoken for might have more testosterone-charged artwork such as Hot T’ Trot, Miss Minooky, Passion Wagon or Ready, Willin’ Wanton, whereas pilots with wives and gals back home might simply paint their betrothed’s name on their fighter’s sides—Dorothy, Glamorous Glennis or Margie Darling.

For the Japanese in the Second World War, their national marking—a simple red circle known as the Hinomaru—was a powerful, elegant symbol of bravery, pride and dominance over lesser humans. The hinomaru, made the official symbol of Japan in 1870, dates back in Japanese history to the 8th century when Emperor Mommu used the device on his court flag. The red circle, the “circle of the sun”, carried messages of brightness, sincerity and warmth, but to the countries and islands which fell under the brutal rule of a martial Japanese Empire in the 1930s and 40s, they were symbols of abject evil, inhuman cruelty and utter domination.

Though the Japanese had been violently gobbling up parts of China and the Far East for the better part of five years, the first true glimpse the western world got of the aerial might of Japan was when the hinomaru flashed in the morning sun over Oahu on that December day of infamy. Image of Aichi Val dive bombers over Pearl from model box by Cyber-Hobby

Though the Western Allies looked upon the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor as treachery of the worst kind, even murder, to the young and incredibly skilled pilots of the Japanese Imperial Navy, it was proof of the unassailable dominance of their warrior culture. For the next months and even years, these young men represented the pinnacle of a warped sense of bushido—the samurai way. It was not the bushido of the 12th century samurai but a new kind, designed to present war as somehow purifying and death in battle an honour and a duty.

At the outset of the Japanese war in China and against the Americans, to be selected for training as an Army or Navy pilot was the greatest honour any Japanese warrior could hope for. The achievements, victories and courage of the Army and Navy pilots were the talk of the home islands. In the final stages of the conflict, as the winds of war blew ill favour towards Nippon, the courage, boldness and pride of the Japanese airman never wavered. In large numbers, the now-poorly-trained remaining pilots willingly took to the skies to fly against the American enemy, with no thought of returning. In tired, damaged and poorly-made aircraft they rolled over one last time into a dive, watching that wing, with its fading hinomaru, drop away to reveal the enemy task force below. With a great sense of pride in their final glory, tears in their eyes for their beloved home, they swept to their deaths as proud Japanese fighter and bomber pilots. For those that remained, it was only a matter of time before they would drink the sake and fight the enemy to the death. They no longer had the momentum, the weapons, the industry, the ability to win, but there is no doubt they still had immense pride in who they were. Then they heard the voice of their Emperor for the first time.

He was asking them to do the single most dishonourable thing they could think of—surrender. Many Japanese officers would kill themselves rather than surrender; many would vow to fight on to the death. One soldier in the Philippines, Hiroo Onoda, continued fighting from the jungles of Lubang Island for thirty more years (he died just two weeks before this story was first written —16 January 2014). In light of this powerful, nearly pathological sense of Japanese aviators’ pride in themselves, their service and Japan, the aircraft which would carry delegations for peace talks would themselves become flying white flags of surrender—an almost unbearable indignity.

With the onslaught of kamikaze attacks, suicidal charges and mass Masada-style suicides of both belligerents and civilians, the Americans had no trust in Japanese envoys who might just as easily immolate themselves as actually surrender. General Douglas MacArthur required, as proof of their peaceful intentions, that the aircraft carrying the envoys from Japan to Iejima (Ie Shima to the Americans), the small Okinawan island designated as the trysting place, be painted white all over and that their beloved, honoured, ancient, and storied hinomarus be painted over in white and then replaced by the Christian cross... a green Christian cross.

Related Stories

Click on image

One can only imagine the emotions, the utter indignity of what this meant to the Japanese who had to mix the paint and spray it over the marks of Japanese courage and honour that were the red hinomarus. Say all you want about Japanese cruelty and behaviour during the war, there is no denying their pride, sense of duty and honour and their personal courage. There was a code, a warrior brotherhood, a history of truths, legends and myths, and it was all over-sprayed in the battle colour of failure—white. The instructions to end the war immediately were clear, and the indignity was given to the aviators... the first to strike at the Americans on December 1941.

The following are the two radio messages sent to the Japanese on the morning of 15 August 1945, which set in motion the eventual unconditional surrender:

At 0930 hours:

I have been designated as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, the United States, the Republic of China, the United Kingdom, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and empowered to arrange directly with the Japanese authorities for the cessation of hostilities at the earliest practicable date.

It is desired that a radio station in the Tokyo area be officially designated for continuous use in handling radio communications between this headquarters and your headquarters. Your reply to this message should give all signs, frequencies, and station designations.

It is desired that the radio communications with my headquarters in Manila be handled in English text. Pending designation by you of a station in the Tokyo area for use as above indicated, stations JUM, repeat JUM, on frequency 13,705, repeat 13,705, kilocycles, will be used for this purpose; and WTA, repeat WTA, Manila, will reply on 15,965, repeat 15,965, kilocycles.

Upon receipt of this message acknowledge. MACARTHUR

Just 22 minutes later, MacArthur gave the very specific instructions of how the Japanese were to prove their peaceful intentions.

At 0952 hours:

Pursuant to the acceptance of the terms of surrender of the Allied Powers by the Emperor of Japan, the Japanese Imperial Government, and the Japanese Imperial Headquarters, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers hereby directs the immediate cessation of hostilities by the Japanese forces. The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers is to be notified at once of the effective date and hour of such cessation of hostilities, whereupon the Allied forces will be directed to cease hostilities.

The Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers further directs the Japanese Imperial Government to send to his headquarters at Manila, Philippine Islands, a competent representative empowered to receive in the name of the Emperor of Japan, the Japanese Imperial Government, and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters certain requirements for carrying into effect the terms of surrender. The above representative will present to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers upon his arrival a document authenticated by the Emperor of Japan, empowering him to receive the requirements of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

The representative will be accompanied by competent advisers representing the Japanese Army, the Japanese Navy, and Japanese Air Forces. The latter adviser will be one thoroughly familiar with airdrome facilities in the Tokyo area.

Procedure for transport of the above party under safe-conduct is prescribed as follows: The party will travel in a Japanese airplane to an airdrome on the island of Ie Shima, from which point they will be transported to Manila, Philippine Islands, in a United States airplane. They will be returned to Japan in the same manner. The party will employ an unarmed airplane, type Zero, model 22, L2, D3.

Such airplane will be painted all white and will bear upon the side of its fuselage and the top and bottom of each wing green crosses easily recognizable at 500 yards. The airplane will be capable of in-flight voice communications, in English, on a frequency of 6,970 kilocycles.

The airplane will proceed to an airdrome on the island of Ie Shima, identified by two white crosses prominently displayed in the center of the runway. The exact date and hour this airplane will depart from Sata Misaki, on the southern tip of Kyushu, the route and altitude of the flight, and estimated time of arrival in Ie Shima will be broadcast six hours in advance, in English, from Tokyo on a frequency of 16,125 kilocycles. Acknowledgment by radio from this headquarters of the receipt of such broadcast is required prior to take-off of the airplane. Weather permitting, the airplane will depart from Sata Misaki between the hours of 0800 and 1100 Tokyo time on the seventeenth day of August 1945. In communications regarding this flight, the code designation “Bataan” will be employed.

The airplane will approach Ie Shima on able course of 180 degrees and circle landing field at 1,000 feet or below the cloud layer until joined by an escort of United States Army P-38’s which will lead it to able landing. Such escort may join the airplane prior to arrival at Ie Shima. MACARTHUR

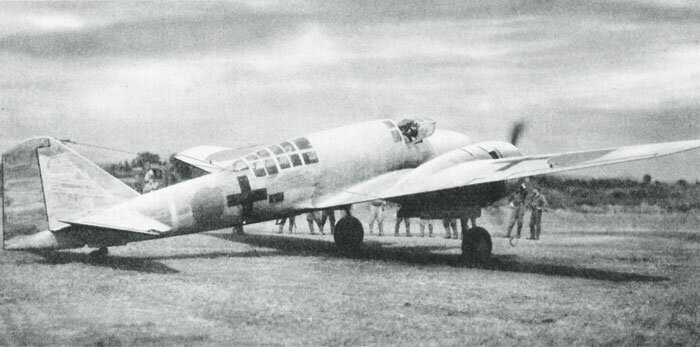

Four days later, two all-white, twin-engined bombers took off from the Tokyo area—one a Mitsubishi G4M1-L2 (Betty) transport aircraft, and the other a bullet-holed Mitsubishi G4M1 (Betty) bomber stripped of its guns. They reached Sata Misaki on the southern tip of Kyushu at about 1100 hrs. They then proceeded on a course of 180 degrees to a point 36 miles North of Iejima Island, off the southwestern coast of Okinawa, and began to circle at 6,000 feet. They were soon joined by B-25 Mitchells from Iejima and top covering P-38 Lightnings, wary that some suicidal aviators may try to stop the peace talks.

On landing at the tiny island, called “Peanut” Island by Okinawans, weary warriors, both Allied and Japanese, who had spent three long years shooting, knifing, burning and slaughtering each other, wallowing in violence and bloodshed, convinced the other was subhuman, met for the very first time in peace and looked each other in the eye and touched each other. One can only imagine how the young Japanese pilots felt as they touched down amidst thousands of young American men, who just the day before would have killed them on sight. The young pilots wore brand new flight suits and flight boots for the trip, but their aircraft were, like the rest of Japan, just barely holding on to dignity. With their proud symbols banned from the meeting, whitewashed and over painted with the cruciform of defeat, a new story of peace was now written in the paint of their aircraft.

The flight of these two Bettys became known as the Green Cross flights and the technique became the standard operating procedure for Japanese aircraft carrying envoys for surrender across the remnants of the Japanese empire for the next month. The only Japanese aircraft flying unmolested had to be approved and had to cover their old markings with the approved Green Cross standards. Not every aircraft complied with every detail of the specified paint scheme; not every aircraft was painted white nor every cross painted green, but scores of these surrender aircraft brought about the end of the killing and suffering and the beginning of the healing.

Here, collected from the internet, are photographs of some of those Green Cross flights and Green Cross aircraft, starting with the most photographed of them all—the Green Cross Bettys of Iejima.

Let the surrender begin. B-25J Mitchell bombers of the 345th Bomb Group (The Apaches) lead two Green Cross Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” medium bombers into the island of Iejima (called Ie Shima by the Americans). The 345th Bomb Group (the 498th, 499th, 500th and 501st Squadrons) was based on Iejima and was given the task and the very special honour of escorting the Bettys from Tokyo to the rendezvous with United States Army Air Force C-54s, which would take the Japanese officers and envoys on to Manila to meet with no less than Douglas MacArthur himself. Photo: USAF

The two Bettys (ironically and deliberately given the call signs Bataan 1 and Bataan 2 by the Americans) fly low over the East China Sea, inbound for Iejima wearing their hastily painted white surrender scheme and green crosses. One can only imagine what is going on in the conflicted minds of the Japanese airmen as they fly over their own territory in the company of the hated enemy, headed for an event of profound humiliation in front of thousands of enemy soldiers. These two Bettys would become the most photographed Green Cross surrender aircraft of the end of the war. Photo: US Navy

A photograph taken from the same 345th Bomb Group Mitchell that is depicted in the first photograph, looking back at another B-25 Mitchell and a B-17. Above, P-38 Lightnings provide top cover. The top cover was needed because some Japanese officials had ordered the remnants of the Japanese Army Air Force to attack and bring down their own bombers rather than surrender. Instead of flying directly to Iejima, the two Japanese planes flew northeast, toward the open ocean, to avoid their own fighters. Photo via warbirdinformationexchange.org

The Betty was officially known as the “Type-1 land-based attack aircraft”, but to its Japanese Navy crews, it was lovingly known as the Hamaki (Cigar), the reason for which is obvious in this photograph (also because one could light it up fairly easily). The Betty was a good performer, but it was often employed in low level, slow speed operations such as torpedo attacks and it had a tendency to explode into flames when hit by even light enemy fire, leading some unhappy pilots to call them the “Type One Lighter” or “The Flying Lighter”. We can clearly see that the Betty’s traditional armament—nose, tail, waist and dorsal guns—have been removed as demanded by the Americans. The B-17 in the distance is from 5th Air Force, 6th Emergency Rescue Squadron carrying a type A-1 lifeboat. The A-1 was dropped by parachute and was motorized. It seems that American authorities did not want to lose these men in the event of a ditching. Photo via warbirdinformationexchange.org

As thousands of American soldiers, airmen, sailors, dignitaries and press photographers on the island of Iejima look to the sky, the two 345th Bomb Group B-25J Mitchells escort the two white Green Cross Bettys over the airfield before setting up for a landing. Photo: James Chastain, 36 Photo Recon Squadron

As thousands of suspicious, curious and anxious young men look on, the Japanese pilot brings his Mitsubishi Betty down on to the bleached coral airfield of Iejima. Note the all-metal Douglas C-54 waiting for their arrival. Photo via Pinterest

It is plainly obvious that in August of 1945, on the island if Iejima, it was brutally hot the day the Green Cross Bettys landed. Here one of the two aircraft drops on to the runway as soldiers, the formal welcoming committee and pressmen wait, finding shade where they could. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

The second of the two Green Cross Bettys makes its final approach while press photographers and reporters capture the long-awaited moment. Photo: James Chastain, 36 Photo Recon Squadron

As the second Betty alights on the coral airstrip, every eye on the island is trained on them. One cannot even imagine what this scene looked like to these Japanese as they looked out from the aircraft windows at a sea of mistrust and a new, grim reality. Photo: James Chastain, 36 Photo Recon Squadron

Another view taken farther back at Iejima shows the two massive and beautifully kept Douglas C-54 aircraft waiting for the passengers of the landing Betty. Image via wwiivehicles.com

With its clamshell canopy open and her Captain standing up to direct his co-pilot through the crowd, the first Green Cross Betty to land at Iejima taxis past a seemingly endless line of enemy soldiers. The scene is one of abject humiliation and intimidation. That pilot must surely have felt the mistrust of the thousands of pairs of eyes burning as he rolled by. Photo: USAAF

A close-up of the Betty taxiing along in front of the thousands of suspicious American servicemen. This had to be intimidating to the Japanese, especially to the lone pilot standing up and accepting the glares of all. Photo: USAAF

I found the personal family memoirs of Army combat engineer Leigh Robertson on the web. Leigh was an eyewitness to the arrival on leshima of the Green Cross surrender aircraft. The following link to his memory of that day is perfect as he immediately wrote it down in a letter back home to his parents.

Sunday, August 19th 1945

Dear Folks,

I don’t know how long it will be until I can mail this letter. I am writing it now, while things are fresh in my mind. I have just seen what is probably the most important event in the world today. It was the arrival of the Japanese envoys on their way to Manila, to sign the preliminary peace agreement with Gen. MacArthur.

We had known for the last three days that they were going to land here. We expected them yesterday, but they were delayed, for some reason. We went to work this morning as usual, and worked until about ten. Then the word went around that the Japs were coming. We piled into trucks and drove up to the airstrip. We waited expectantly for over an hour. Finally, word went out once more that they would not arrive until 1:30 P.M, so we decided to come on back to camp and eat lunch (we had baked ham, by the way). Just before we left we watched two giant four engine transports (C-54s) circle the field and land. These were the planes that would take the Japs on to Manila.

Just as I was leaving the mess hall, the news came over the radio that the Jap planes were circling the island, and sure enough, they were! I ran to my tent, put away my mess gear, grabbed my cap and climbed on a truck.

It is about two miles to the airstrip, but we made pretty good time, because all the traffic was going the same way. As we came closer to the field, we became part of a strange procession. Directly in front and to the rear of us were two P-38s (twin engine fighter aircraft). Further on down the line there were tractors, motor graders, and in fact, most every kind of vehicle you can imagine--all loaded with G.I.s. We parked the truck about a quarter mile from the strip and ran the rest of the way. I got separated from the rest of the men, and stopped on a high spot about 75 yards from the strip. I had scarcely gotten settled when the planes started in for a landing. The planes themselves were Japanese “Betty” bombers, with two engines, bearing some resemblance to our B-26. They were painted white, with green crosses. It had been a hasty paint job—you could still see the red of the rising sun showing through the white. Naturally, the planes had been stripped of all armament. They were escorted by two B-25s, and I don’t know how many P-38s, probably a hundred or more. The latter continued to circle the field for an hour or more, until all the excitement was over.

Both planes made perfect landings, rolled to the far end of the strip, turned and taxied back to our end. They parked right alongside the two large transports that had arrived earlier. They were dwarfed by comparison to our transports.

We were not permitted within a hundred yards or so of the four airplanes. There were several hundred people gathered around the planes, most likely photographers and Air Corps officers. They pretty well hid from view the events of the next few minutes. I could see various people boarding the transport, but couldn’t tell much about them.

Presently they towed one of the Jap planes up a taxiway to a parking area close to where I was sitting. One of our boys pulled his truck right up to the fence, and raised the dump bed. This gave us a grandstand seat, about 15 feet off the ground. When the plane came to rest, the crew started climbing out. There were five in all, dressed in heavy flying clothes. There were two jeeps waiting to take them away. Evidently they didn’t speak English, for there was much waving of hands and shrugging of shoulders. About this time two or three thousand soldiers broke through the ring of guards and started for the Japs. They didn’t have any bad intentions, just curiosity, and wanting to take pictures. I know that if I had been in the place of those Japs, I would have been just a wee bit scared! At any rate, they lost no time in getting into the Jeeps and away from the mob!

Finally, they managed to get the crowd back far enough to bring the other “Betty” over to the parking area. After a few minutes one of the C-47s warmed up its engines and taxied onto the strip. With a mighty roar, she started down the runway. Before she got halfway down the runway, she was in the air, on her way to Manila.

It was a great show, and one I don’t think I shall ever forget, for it is part of the last chapter of this war that has caused so many hardships, and so many heartbreaks. Thank God it is all over.

I wish that you would save this letter for me, or make a copy of it. What I saw today is one of the few things that I have seen, or will see, while I’m in this army that will be worth remembering.

Just as soon as I find out from the censor that it is O.K., I’ll mail this. You will probably have read about it in the newspapers, and seen it in the newsreel, but this may give you a little different slant on it.

I sure do think of you folks a lot. Maybe it won’t be too long now till I can be back with all of you again. I want to write to Barbara tonight, so I’ll end this now.

Love, Leigh

The captain of the second Mitsubishi Betty also stands up to direct his co-pilot through the crowds waiting and watching. We can tell this is a different Betty as the previous one has a window panel just behind the nose glazing under the chin of the aircraft. This one does not have that particular window pane. Photo: Fred Hill, 17th Photo Recon Squadron

With his twin Kasei 14-cylinder engines thundering, the Japanese pilot guides the Betty through the crowded taxi strip. Photo: Fred Hill, 17th Photo Recon Squadron

Guiding his co-pilot from his perch above the Betty, the commander of the second Green Cross Betty commands him to swing round into position near the awaiting C-54 transports of the Americans. In doing so he blasts the crowd of American sailors and airmen. We can see in this photo that all of the men in the background have their backs turned against the dust storm. Perhaps this was the one satisfying moment for the Japanese crews in this most humiliating of days. Photo: Fred Hill, 17th Photo Recon Squadron

One of the two Bettys comes to a stop across from the waiting Douglas C-54 aircraft that will take the envoys to Manila. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

The second Green Cross Betty to land at Iejima begins to unload its passengers and crew, while American soldiers crowd around. The distinguishing features that help us tell this Betty from the other are the different glazing panels on the nose and the fact that this does not have the Radio Direction Finding (RDF) loop antenna on the top of the fuselage. Photo via leighrobertson.net

The two Green Cross aircraft are stared at by thousands of American soldiers, who watch from the gullies surrounding the airstrip, hoping to get a close look at the once hated, now defeated, Japanese airmen. Note the RDF loop antenna at the top of the fuselage. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

American soldiers and airmen, in daily working gear, gawk at the once-hated Mitsubishi G4M Betty painted white like a flag of surrender and no longer wearing her proud red rising sun roundels known as the Hinomaru. Instead they are required to wear green crosses—Christian symbols if there ever were any. With her RDF loop, this is clearly the first of the two Bettys. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

Moments after the second all-white Betty shuts down on the leshima ramp in the blistering sun, she is surrounded by airmen and plenty of Military Police (MPs). While some of the Japanese stand on the ground, a young airman steps out of the doorway carrying two large bouquets of flowers as a peace offering to the American delegation. The offer of the flowers was rejected by the Americans who felt that it was too soon to make nice with the once haughty Japanese who had treated Allied POWs so roughly. It would be like Auschwitz survivors accepting flowers from the SS, but you have to feel sorry for the young man bearing the gift. Photo via warbirdinformationexchange.org

Looking more than a little worried and even terrified, the young Japanese soldiers look about them to see only angry, disdainful faces. The soldier on the left is the one who has just had his gift of flowers rejected and is no doubt looking for a place to hide. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

Japanese officers and leaders, with a mandate to negotiate their surrender, cross from their Mitsubishi Betty to awaiting C-54 aircraft which will take them to Manila. The truth is there were no negotiations. Surrender was unconditional. But they were there to accept the orders of surrender. The formal signing of the surrender would take place aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945 (two weeks later). Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

Formalities on the ground were quickly performed and within 20 minutes, the eight official commissioners were guided up a ladder into a massive Douglas C-54 transport aircraft, a luxurious accommodation when compared to the Japanese Bettys. They were then flown to Manila in the Philippines to meet with MacArthur. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

After the Japanese delegates boarded the American C-54 Skymaster at Iejima, they were flown 1,500 kilometres over the South China Sea to Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Here, we see General Douglas MacArthur watching the arrival of the Japanese entourage from the balcony of the ruined Manila City Hall. Most of the city’s fine old Spanish-style buildings were destroyed in the battle to retake the city from the Japanese in February and March of that year. Americans and Filipino citizens look on warily. More than 100,000 Manilans and 1,000 Americans were killed battling the Japanese, so this crowd would not be considered to be welcoming. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

The aircrew from one of the Green Cross Bettys shelter from the sun under the wing of their aircraft. With such extreme sunlight, white coral airstrip and white airplane, it is easy to see how the photographer, exposing for the men, had the entire background washed out. However, we can just make out the green cross on the fuselage and one higher on the tail. Notice how none of the airmen are looking directly at the photographer, indicating submission. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center

Chief Warrant Officer James Chastain, an air force photographer/photo lab technician, with camera in hand, gets one of his buddies to snap a photo of him with a Green Cross Betty. Of that day, Chastain remembers, “Prior to the envoys landing, GI troops had been positioned approximately six feet apart on either side of the landing runway. One of the Betties [sic] had part of the Plexiglas of the tail gunner’s position missing and the person in that position could be plainly seen. As the Betty settled to the runway for a less than perfect landing the person in the tail gunner’s position saw all of the people standing behind the GIs that lined the runway and it appeared that he wasn’t sure what action our guards were going to take, he immediately scurried forward out of sight. Massive rolls of barbed wire prevented us getting in position for close up shots of the Envoys transfer to the awaiting C-54s. Later when we were able to view the Betties more closely, one could see that paint jobs were slightly streaked as if they had been hurriedly applied by brush. One could even see the old red “meat Ball” through the thin white paint. However the green crosses had been applied with more care.” Photo: via James Chastain, 36 Photo Recon Squadron

Another view of the first two Green Cross aircraft at Iejima—Bataan 1 and Bataan 2. Photo: John F. DeAngelis, via bristolpress.com

The two Green Cross Bettys would stay until the delegation returned the next day from Manila. During that time a group of airmen, sailors, and Seabees gathered for a victory photograph like no other, on top of the first Betty to land. The baffed-out Bettys were in rough shape compared to the C-54s the delegation used to get to Manila and we can see pools of oil and fuel beneath this one. Photo via axis-and-allies-paintworks.co

As if being humiliated in surrender, painting over your proud symbols and having your airplane walked on by victorious American boys wasn’t degrading enough, one of the Bettys ran off the taxiway the next day, delaying departure while exasperated Japanese airmen tried to extract the aircraft from the soft coral, earth and embarrassment.

A modeller shows us exactly what the Green Cross Betty would have looked like. One can only imagine the emotions running through the ground crews who were required to paint over their much-adored hinomaru markings and remove her defensive armament. This is the bomber variant of the G4M Betty, while the second aircraft to land was a transport variant. Photo via network54.com, model by Terry aka braincells37

From down in the gully alongside the Iejima airstrip, another photographer takes a colour shot of Betty known as Bataan One. Photo via axis-and-allies-paintworks.com

A colour profile of the Green Cross Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber (Bataan One) used for the Iejima rendezvous. This gives us a truer sense of the colour of green used. Image via Wings Palette

The island of Iejima today. In 1945, it was the place where the Japanese and the Allies met in peace for the first time in nearly four years. Today, the 9-square-mile farm island is sometimes called “Peanut Island,” for its general shape and peanut crop, or “Flower Island,” for its abundant flower production. Photo via Wikipedia

Even training aircraft like this Kyushu K11W1 Shiragiku (White Chrysanthemum) bombing trainer were painted white with green crosses if they were used to transport emissaries to surrender and peace talks somewhere. Here we see that the thin coat of white paint is barely enough to cover the Hinomaru in this hangared Shiragiku. The pinkish Japanese roundel is covered by a green cross, as this aircraft was somehow used to transport a surrender delegate. Photo via Illinois Institute of Technology Downtown Campus Library as part of the Library of International Relations Collection

From Kamikaze to Green Cross. The same Shiragiku from the previous photograph is pushed outside by American ground crews. The Kyushu K11W Shiragiku, or White Chrysanthemum, was a land-based bombing trainer aircraft, serving in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service in the latter years of the Second World War. It was designed to train crews in operating equipment for bombing, navigation, and communication. A total of 798 K11Ws were manufactured and these aircraft were also used in kamikaze missions during the last stages of the Pacific War. Photo via mission4today.com

K11W Shiragiku in postwar markings of white overall with green crosses. The aircraft was so obscure and little known to the Allies, that it never got an allied code-name like Betty, Zeke, George or Tony. This one wears the numeral “1” on its tail. Image scanned from The Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II by David Mondey

Another Green Cross K11W Shiragaku with the numeral “2” on its tail but with very similar painted-out markings beneath its canopy as are seen on the hangared Shiragaku previously depicted. This particular aircraft was photographed at Shanghai in late 1945. One wonders if this is the same aircraft or at least from the same training base in Japan. Note the American C-46 Commandos in the background. Photo via Flickr

A Nakajima B5N2 Kate in near perfect Green Cross markings seems discarded and shoved haphazardly together with other Japanese aircraft. Photo via H.J. Nowarra, The Bill Pippin Collection, 1000aircraftphotos.com

One of the most attractive Japanese aircraft of the Second World War was the Mitsubishi Ki-46 Dinah. Here we see a Green Cross Dinah leaving the plateau airfield of Vunakanau, outside of Rabaul with a delegation to work out the details of the surrender of the Japanese Army and Navy to the Royal New Zealand Air Force at Jacquinot Bay, New Britain. The Japanese who painted this aircraft either misunderstood the order to paint out the Hinomaru marking or just plain couldn’t do it, as the aircraft carries both the red “meatball” and the Green Cross of surrender. Jacquinot Bay Airport (IATA: JAQ) is today an airport near Jacquinot Bay in the East New Britain Province on the island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea. The airstrip was liberated by the Australian Army in 1944. Following the Japanese surrender, several Japanese aircraft were flown from Vunakanau Airfield to Jacquinot Bay Airfield. Photo via Flickr

Another shot of the Ki-46 Dinah from the previous photograph—this time at her destination at the RNZAF field at Jacquinot Bay. In this photograph we can see much more clearly the dual markings of aggression and surrender. Photo via Woody01 at Kiwisim.net.nz

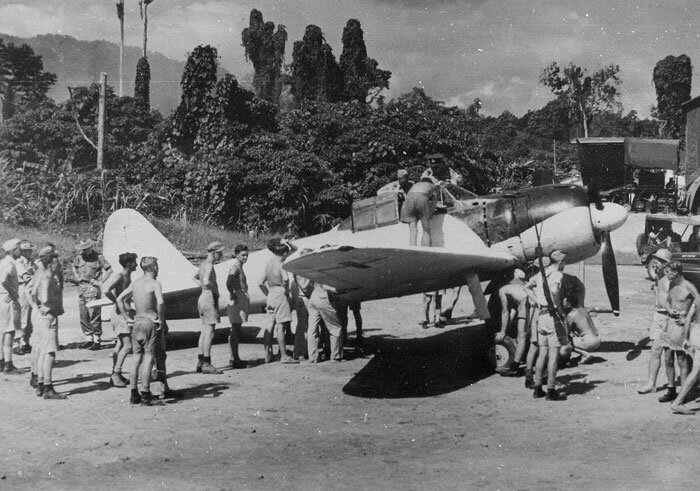

Four surrendered Japanese aircraft after arrival at the RNZAF airfield at Jacquinot Bay, New Britain, on 18 September 1945 (a full month after the Iejima Green Cross flights). The formation consisted of three Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 Zero fighters of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and one Ki-46 Dinah reconnaissance aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Army (see previous photograph). The aircraft were flown by Japanese crews, and departed Vunakunau Airfield at Rabaul with an escort of RNZAF F4U Corsair fighters. All the Japanese aircraft wore Green Cross surrender markings. Image from Australian War Memorial via Wikipedia

Royal New Zealand Air Force officers and airmen take a good look at one of the Japanese Zeros flown to Jacquinot Bay, New Britain by Japanese pilots under guard from RNZAF Corsairs. Photo via Woody01 at Kiwisim.net.nz

In the background, RNZAF ground crew work on one of the three Jacquinot Bay Zeros, while in the foreground we see one chocked and waiting for a test flight perhaps. Photo via Woody01 at Kiwisim.net.nz

RNZAF ground crew inspect and work on one of the Green Cross Zeros surrendered at Jacquinot Bay, New Britain. Photo via Woody01 at Kiwisim.net.nz

With Japanese soldiers watching, one of the Jacquinot Bay Mitsubishi Zeros rolls for takeoff while another warms up in the background. Photo via Australian War Memorial

I guess it’s fair to say that the markings on this Mitsubishi Ki-57 passenger transport aircraft are, well... Topsy Turvy. The allied code-name for the type was Topsy. The Topsy was the main personnel transport aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second World War, and was developed from the Ki-21 twin-engined heavy bomber. The Ki-57 was used as a communications aircraft, for logistical transport and as a paratroop transport, and served on every front where the Japanese Army was involved. Photo via wwiivehicles.com

A Green Cross Jake is readied for takeoff from Jacquinot Bay, New Britain in October of 1945. This Aichi E13A1 Jake long-range reconnaissance float plane was surrendered to the Royal New Zealand Air Force personnel after it landed on the surface of Jacquinot Bay. While floating there, it developed a leak in a pontoon and sank. It was not recovered. Photo: RNZAF via Australian War Memorial

Nattily dressed Japanese surrender envoys including General Numata Takazo are escorted by RAF and British Army officers to the interrogation building after their arrival at Mingaladon airfield, Rangoon for their surrender of the Japanese Southern Army in Burma. The date was 28 August 1945. The Green Cross aircraft used for this flight in the foreground is also a Mitsubishi Ki-57 Topsy. The aircraft in the background is possibly a Dinah. Photo: Pilot Officer Ashley, RAF via Imperial War Museum

A rather tall and fearsome-looking Commander S. Kusumi (with Samurai sword), a naval officer on the staff of Field Marshal Terauchi, Supreme Commander of Japanese Forces (Southern Region), arrives at Mingaladon airfield, Rangoon, via the hastily marked Mitsubishi Ki-46 Dinah in the background to take part in the surrender negotiations. Photo: Sergeant Bradley, RAF Photographer via Imperial War Museum

A photo of two hangared Green Cross aircraft, possibly at Seletar Airfield in Singapore. The one in the foreground is a Mitsubishi Ki-57 Topsy, while the larger aircraft (likely also in Green Cross markings) at the back is a Showa/Nakajima L2D, called a Tabby by the Allies. The Tabby was a license-built copy (with modifications like the extra cockpit windows) of the Douglas DC-3, though it is unlikely that the Japanese continued to pay the license fee once the war started. Photo via aviationofjapan.com and Tadeusz Januszewski

Another photo from Seletar, Singapore, showing a Mitsubishi G3M Nell and another Tabby aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 13th Air Fleet. The Nell, one of Japan’s earliest heavy bombers (introduced in 1935) was also a transport aircraft like this variant. From 1943, most of the remaining Nells served as glider tugs, aircrew and paratroop trainers and for transporting high-ranking officers and VIPs between home islands, occupied territories and combat fronts until the end of the war. Note the blunt-looking forward turret which was retractable, but is extended in this shot. It was considered too “draggy” and was rarely extended. Photo via aviationofjapan.com and Tadeusz Januszewski

The Japanese ground crew tasked with painting this Mitsubishi Ki-46 Dinah either had only a small amount of white paint or they didn’t have time to paint the whole aircraft. The Dinah was photographed at Atsugi Airfield. Atsugi is a naval air base located near the cities of Yamato and Ayase in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. Photo via flickriver.com

A Mitsubishi Ki-57 Topsy with markings that make her appear to be more Red Cross than Green Cross in black and white. Photo via forum.axishistory.com

Followed by jeeps of the Royal New Zealand Air Force, a Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero, flown by a pilot of the RNZAF lands at Piva airfield in Southern Bougainville, New Britain in September of 1945, after having been flown from Kara. It was discovered there in close-to-flying condition nearly two years before. Not trusting the Japanese pilot who assisted in getting it airworthy, the RNZAF pilot, Wing Commander Bill Kofoed, decided to fly it out of the remote airfield—where it had been hidden—with the landing gear down all the way. As he was flying over 200 miles of Kiwi-held territory and did not have full official authorization, he smartly painted the Zero with Green Cross surrender markings. Note the RNZAF Corsairs in the background. Photo: Royal New Zealand Air Force

Wing Commander William Kofoed, RNZAF, poses with the Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero (Reisen) at Kara airstrip on 15 September 1945 before flying it out to Piva. Photo: RNZAF

Kiwi airmen line up at Piva to get a good look at the Kara Zero just moments after it landed. As seen previously, three other Zeros had landed at Jacquinot Bay and were handed over to the RNZAF. Of these, two were given to the Royal Australian Air Force and the other was flown about as a joyride aircraft by curious pilots. Given the lack of official interest in the Jacquinot Bay Zeros, Kofoed decided to pack his Zero off to New Zealand to save it—ASAP. It rode as deck cargo on the inter-island ferry Wahine which was then employed in repatriating Kiwi personnel to New Zealand. Photo: Royal New Zealand Air Force

In Piva airfield in New Britain, Wing Commander Kofoed’s war prize is inspected by members of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Photo: Royal New Zealand Air Force

The same Zero at Piva has been readied for transport aboard the ferry Wahine to New Zealand as a war prize—with propeller and horizontal stabilizers removed for travel. Photo via State Library of Queensland

Today, the Kara Zero has been restored with it original Hinomaru markings and is on display at the Auckland War Memorial Museum

Another Mitsubishi Zero with ersatz Green Cross markings—a white square with cross and the wing hinomarus replaced by simple white squares and no crosses. Like pretty well every Japanese aircraft surrendered, captured or found, it is not in flyable condition with a missing starboard wheel and damaged left wheel. Photo via aviarmor.net

These Green Cross Mitsubishi Bettys are painted in the surrender markings but appear to have had their propellers removed. These are not the Iejima Bettys. Photo via historybanter.com

An entire flight line in Matsuyama airfield on Formosa (now Taiwan) wears Green Cross markings, including several Mitsubishi Ki-67 Hiryu (Flying Dragon) heavy bombers. Photo via ijaafphotos.com

Two Japanese Green Cross aircraft at Labuan—an island off the coast of Borneo in East Malaysia. The Mitsubishi Ki.21 heavy bomber aircraft (allied code-name Sally) (left) has been painted white with a green surrender cross, and was used to transport Japanese prisoners for trial between Borneo and Labuan. This aircraft was probably the Sally which was flown to Australia in February 1946, having been nicknamed Tokyo Rose. The Tachikawa Ki.54 transport aircraft (allied code-name Hickory) (right) has not been painted white but its hinomaru fuselage marking has been transformed with a white surrender cross over the red circle and the wings carry white crosses next to the red meatballs. The Hickory was used to fly Lieutenant General Masao Baba, Commander of the Japanese 37th Army and Supreme Commander of the Japanese Forces in Borneo, to surrender at Labuan. Photo via Australian War Memorial

The same Tachikawa Ki.54 Hickory as in the previous photo is a good example of surrender markings being either misinterpreted or simply ignored. It sports a white surrender cross over its fuselage Hinomarus and a white cross side by side with the meatballs under the wings. Photo via Australian War Memorial

A Japanese Nakajima Ki-49, Army Type 100 heavy bomber, allied code-name Helen, taxiing after landing on the Pitoe airstrip on Morotai, carrying some of the staff of the commander of the Second Japanese Army, Lieutenant General Fusataro Teshima, on 9 September 1945. As the Japanese were short of serviceable aircraft General Teshima arrived from Pinrang in an RAAF C-47 to surrender the Japanese Second Army to General Sir Thomas Blamey. Note the unusual drogue attached to the tail and the American B-24 Liberator in the background. Photo via Australian War Memorial

A Japanese Mitsubishi Ki-21, Army Type 97 heavy bomber, allied code-name Sally, leading the Nakajima Ki-49, Army Type 100 heavy bomber, (from the previous photo), off the Pitoe airstrip. Both Green Cross aircraft are carrying some of the staff of the commander of the Second Japanese Army, Lieutenant General Fusataro Teshima. Photo via Australian War Memorial

After coming to a stop at Pitoe airfield, the Helen is surrounded by curious Australian airmen. Photo via Australian War Memorial

Wherever Green Cross surrender aircraft went, they were sure to attract every Allied airman, sailor and soldier from miles around—curious to see a Japanese aircraft up close, but even more so to see a Japanese serviceman up close and humbled. Photo via Australian War Memorial

The surrender arrangements dictated by the Allies specified that aircraft carrying peace delegates (or even flying anywhere for that matter) were to be painted white overall and carry the green cross instead of a red hinomaru. This was done to display the peaceful intentions of an army and a navy that was altogether mistrusted by the Allies. In the specific case of a massive four-engined flying boat like the gorgeous Kawanishi H6K Mavis, it was quite possible that the Japanese maintainers would not have the time or the paint to get it fully white. The Mavis in this photograph has only half the fuselage painted as per surrender specs. Photo: USAAF via Major Robert C. Mikesh

The same Kawanishi Mavis flying boat from the previous photograph lies anchored and displaying white outlined green crosses applied right over her red hinomaru markings, which are still visible. Photo via theminiaturespage.com

![Chief Warrant Officer James Chastain, an air force photographer/photo lab technician, with camera in hand, gets one of his buddies to snap a photo of him with a Green Cross Betty. Of that day, Chastain remembers, “Prior to the envoys landing, GI troops had been positioned approximately six feet apart on either side of the landing runway. One of the Betties [sic] had part of the Plexiglas of the tail gunner’s position missing and the person in that position could be plainly seen. As the Betty settled to the runway for a less than perfect landing the person in the tail gunner’s position saw all of the people standing behind the GIs that lined the runway and it appeared that he wasn’t sure what action our guards were going to take, he immediately scurried forward out of sight. Massive rolls of barbed wire prevented us getting in position for close up shots of the Envoys transfer to the awaiting C-54s. Later when we were able to view the Betties more closely, one could see that paint jobs were slightly streaked as if they had been hurriedly applied by brush. One could even see the old red “meat Ball” through the thin white paint. However the green crosses had been applied with more care.” Photo: via James Chastain, 36 Photo Recon Squadron](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1625877183090-Y30MNWIOM3QRRWVAUO8F/8861FF3C-A4C3-4B31-B51F-CB7AA5371072.jpeg)