FOR GOD AND COUNTRY

No one has ever accused me of being a religious man. Not in the last four decades anyway. Perhaps it was all those years as an altar boy trudging to church through ice pellets and snow squalls at 5 AM during a black-as-night Canadian winter morning, my heavy boots squeaking on the hard snow. Perhaps it was the hundreds of masses I served in an overheated church where I knelt, rang hand bells, yawned and teetered on the edge of sleep while Monsignor Costello droned on in Latin for the benefit of one lonely lady and the Organ Master.

On two occasions in those days, I was stopped in the frozen, black, suburban void of Elmvale Acres two hours before sun-up by the single cherry-red light of a prowling police cruiser. What, in God's name, I was asked, was a freckle faced 12-year old kid in dufflel coat, ear muffs and Second World War flight boots doing in a world that belonged to sidewalk sanders, milkmen and officers of the law?

One day about 40 years ago, much to the silent displeasure of my papist father, I stopped going to church all together, and I have never entered a church since that day with the intention of praying or finding solace and contemplation. I have never since that day felt a spirit dwelling in any church that I have visited for weddings or funerals. Perhaps there was a spirit, but I have not been able to feel it.

That all changed last fall when visiting London on Vintage Wings of Canada business. One of the places I was hoping to visit on my down time was a small (by Westminster standards) church buried deep in one of the most historic sectors of London. The Church of St. Clement Danes first came to my attention while watching a video on the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. During that documentary, the Flight was honoured with their unit crest being carved in slate and embedded in the floor of this unique and beautiful church. I had never before heard of this practice, this place of worship, this glorious tradition. I made it an imperative to visit while in London.

The site of St. Clement Danes on the Strand has been a place of worship for more than 1,200 years and the church structure that stands on it now has been here for 330 years. The main structure was designed by none other than Christopher Wren, the best known and highest acclaimed architect in British history. After the Great London Fire of 1666, Wren was tasked with the rebuilding no less than 51 razed churches in the City of London alone. One was St. Clement Danes, while one was his the crowning masterpiece of his life's work - St. Paul's Cathedral. Having a university degree in architecture, I was doubly excited to behold one of his buildings for the first time.

An historic photograph of St. Clement Danes around the turn of the 20th century. The first church on the site was reputedly founded by Danes living nearby in the 9th century. The location, on the river between the City of London and the future site of Westminster, was home to many Danes at a time when half of England was Danish; being a seafaring race, the Danes named the church they built after St Clement, patron saint of mariners. King Harold I "Harefoot" was buried here in March 1040 after his body was disinterred by his briefly usurped brother Hartha-Canute, and thrown into the marshes bordering the Thames. The church was first rebuilt by William the Conqueror, and then again in the Middle Ages. It was in such a bad state by the end of the 17th century that it was demolished and again rebuilt from 1680-1682, this time by Christopher Wren. The steeple was added to the 115 foot tower from 1719-1720 by James Gibbs. Photo via Bishopsgate Institute/London and Middlesex Archeological Institute - LAMAS Glass Slide Collection

While a religious edifice of some kind has endured here since 600 years before Columbus discovered the New World, in all that time none of the buildings found here were ever draped in the glory, honour, sadness and history now found contained within its present four walls. But to get to that glory, first St. Clement Danes had to face its own trial by Satan's fire and a scourging by the whips of blasted metal from the angels of darkness.

On the night of the the 10th of May, 1941 and into the morning of the 11th, the St. Clement Danes on the Strand was ravaged by direct hits from incendiary bombs and viciously lashed by huge chunks of shrapnel from near misses of high explosive aerial bombs. Satan's dark angels in the form of Hitler's Heinkels dropped load after load on central London in what was to be for all intents and purposes the last night of the Blitz.

On this night, which was to be the last major attack on London, the Luftwaffe amassed 550 bombers. When the sun came up on the 11th of May, St. Clement Danes was a smoking shell and many other important buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged including The Houses of Parliament, the British Museum and St. James Palace. The death toll that night was 1,364 Londoners killed and 1,616 seriously injured. After the "All Clear", the steady and determined British set to work to clear the rubble, bury their dead and get back to the business of defeating the Evil Empire.

St Clement Danes Church in The Strand ablaze following direct hits by incendiary bombs and near misses from high explosives on the night of 10th/11th May 1941. As a result of the German bombing, the church was completely destroyed with only the four walls and spire remaining standing. Following an appeal from the RAF, the church was re-dedicated in 1956 as the Central Church of the RAF and today remains as a wonderful legacy to Wren's original design and the painstaking rebuilding work of the 1950s. Photo courtesy of Steve Hunnisett of Blitzwalkers

Related Stories

Click on image

After the bombing of the church, only the outer walls and the Gibbs spire remained. In addition to the blackened stone we can also see the scars of her shrapnel lashing. For several years it remained thus. Because of its destruction at the conclusion of the London Blitz, the Royal Air Force petitioned to have it consecrated as their Central Church – the symbolism of the choice is hard to miss. In 1953 the church was handed into the keeping of the Air Council and a world-wide appeal was launched to rebuild St Clement Danes. Bequests and donations from organisations and individuals poured in so that the necessary £250,000 (that’s over £4m in current funds) was raised and within two years restoration work could begin. Re-consecrated in 1958 as a perpetual shrine of remembrance to those killed on active service and those of the Allied Air Forces who gave their lives during the Second World War, it is a living church prayed in daily and visited throughout the year by thousands seeking solace and reflection. Photo via the RAF and St. Clement Danes

An aerial photograph of The Strand including both St. Mary Le Strand (top) and St Clement Danes (bottom) shows us clearly that after the damage of the Second World War, the church remained as a gutted shell until the RAF secured it for their Central Church. Following the Strand further past St Mary's one comes to Trafalgar Square. St Clement Danes lies half way between St. Paul's and Trafalgar Square. Photo via the RAF and St. Clement Danes

The damage suffered that terrible night in May of 1941 is still evident to this day. The side and rear of the building is riddled with vicious scars from shrapnel. One can only imagine the terrible danger endured by London's brave firefighters who fought these fires while the bombs were dropping. Photo by Steve Hunnisett of Blitzwalkers

After the war, the ruin that was Wren's beautiful and elegant work was left until its future could be secured. Because the church was burned but still standing as a result of the German attacks, it came to symbolize, along with the pilots of the Battle of Britain, the strength of the British resolve in the face of dire circumstance. And because it was damaged as the result of a to-the-death aerial war that was eventually won by the Royal Air Force, the church was handed over to them in 1953. Following an appeal for funding that secured £ 250,000 and reached around the world to the airmen and air forces of the Commonwealth, the church was restored to its original Christopher Wren beauty.

In 1958, St. Clement Danes was consecrated as the Central Church of the Royal Air Force and opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Today the church stands as a living and growing spititual tribute to the sacrifices of the airmen of the Commonwealth during the Second World War and to the continuing sacrifices of the RAF to this very day.

Every inch of the walls, floor and ceiling is a memorial of some kind to airmen. Above the balcony hang a number of stood down unit colour standards. Below each lower window is a glass case above which stands an eagle and in which sits a book of remembrance - one airman to a page. The 8th and 9th US Air Forces stationed in the United Kingdom during the war years are included with a shrine. The whole ground floor is a sweeping plain of white stone patterned by a seeming endless galaxy of 1,000 insets of Welsh slate in the shape of RAF unit badges. A special stone and brass mosaic at the entrance has the crest of the RAF surrounded by eight crests of the Commonwealth air forces (some of which no longer exist), while another in the left aisle has the Polish eagle surrounded by the armorial symbols of the sixteen Polish squadrons of the RAF during the Second World War.

Gift tributes found throughout the church include: the altar from the Netherlands, the lectern from the Royal Australian Air Force, a chair from Douglas Bader to the memory of his first wife - Thelma who died in 1971, a chair honouring surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe and The Guinea Pig Club, and a processional cross from the Air Training Corps. The organ on the balcony at the rear was a gift from the US Air Force. The basement crypt has been made into a quiet and secluded chapel, with an altar from the Netherlands Air Force, a baptismal font from the Norwegians, and a candelabrum from the Belgian Air Force.

The carillon bells were hung in 1957 with a big bass bell nick-named “Boom” in commemoration of Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Trenchard, GCB OM GCVO DSO who organised the RAF from its inception. “Boom” Trenchard had just died the year before the bells were hung.

The author walks across The Strand towards St Clement Danes. In summer, trees obscure much of the Christopher Wren designed church. A couple of blocks away down The Strand, stands the similar St. Mary Le Strand church which many (judging by the erroneous captions on Flickr) take to be St. Clement Danes when sorting through their photos post visit. Photo by Susan Kirkpatrick

In this photo by Iranian photographer Aria Mehr, we have a much better view of St Clement Danes' site and surrounding buildings. The statue at the front right is that of Hugh Dowding, chief of RAF Fighter Command at the time of the Battle of Britain. Photo by Aria Mehr

Most Christian churches have statues on their grounds of saints and other religious figures. St Clement Danes is no different - with statues celebrating the canonized "saints" of the Royal Air Force. This statue of Air Chief Marshall Hugh Dowding, the architect of fighter command, stands outside the church. He was Commander-in-Chief, Fighter Command of the Royal Air Force from 1936 - 1940. In 1940, Dowding, nicknamed "Stuffy" by his men, proved unwilling to sacrifice aircraft and pilots in the attempt to aid Allied troops during the Battle of France. He, along with his immediate superior Sir Cyril Newall, then Chief of the Air Staff, resisted repeated requests from Winston Churchill to weaken the home defence by sending precious squadrons to France. Beyond the critical importance of the overall system of integrated air defence which he had developed for Fighter Command, his major contribution was to marshal resources behind the scenes (including replacement aircraft and air crew) and to maintain a significant fighter reserve, while leaving his subordinate commanders' hands largely free to run the battle in detail. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris, 1st Baronet GCB OBE AFC (13 April 1892 – 5 April 1984), commonly known as "Bomber" Harris by the press, and often within the RAF as "Butcher" Harris, was Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) of RAF Bomber Command (from early 1943 holding the rank of Air Chief Marshal) during the latter half of World War II. In 1942 the Cabinet agreed to the "area bombing" of German cities. Harris was tasked with implementing Churchill's policy and supported the development of tactics and technology to perform the task more effectively. Harris assisted British Chief of the Air Staff, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Portal, in carrying out the United Kingdom's most devastating attacks against the German infrastructure at a time when Britain was limited in its resources and manpower.

The erection of the statue of Harris was controversial due to his responsibility in the firebombing of Dresden and other bombing campaigns targeted at civilians. Despite protests from Germany as well as some in Britain, the Bomber Harris Trust (an RAF veterans' organization) erected a statue of him outside the RAF Church of St. Clement Danes in 1992. It was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother who looked surprised when she was jeered by protesters. The line on the statue reads "The Nation owes them all an immense debt". The statue had to be guarded by policemen day and night for some time as it was frequently sprayed with graffiti. Photo by Dave O'Malley

This beautiful painted wrought iron cross is mounted next to the church's entrance doors and proclaims for all who visit that this is no ordinary religious edifice. Three details are worthy of note - two small gold flames representing her trial by fire, two small gold wings representing flight and at the bottom (not in this shot), an anchor representing naval fliers. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Putting St. Clement Danes in perspective. A nice photo by Brazilian photographer Gustavo Alterio shows a view from the top of St. Paul's Cathedral back down The Strand towards Trafalgar Square. Two rectangles highlight two famous churches - St. Brides (closest) and St. Clement Danes - barely visible in the distance. Photo by Gustavo Alterio

I suppose that part of my problem with the spirituality of churches stems from inside myself. If unable to open a door inwards I could hardly expect to access whatever lay behind the doors of these buildings. There was of course this one very powerful exception. Walking down the Strand from Trafalgar, the knowledge of where I was and of what happened there 70 years ago was like a crowbar to the jamb of that inner door. The closer I got to the church, the more that door was forced open and as I walked though the doors of St. Clement Danes, some huge wind of release threw that heavy gate solidly back. This church was clearly different and so was my openness.

Somewhat soiled and grey on the outside and pockmarked by shrapnel, the interior is a sunlit sanctuary that begs for silence, encourages contemplation and awards the visitor with a spiritual warmth. There is a spirit of triumph and yet there is a lesson on human failure here too - how they blend so well is a mystery. Gold leaf, carvings, military colours, holy names and an ocean of squadron crests speak to glory, history and accomplishment, while the totality of the sacrifice of airmen and women during the wars of the 20th century hangs like smoke in the air. The place is a strange mixture of uplifting, soaring euphoria and heavy, crushing sadness. These equal and opposite emotional effects serve to keep the visitor solidly and powerfully centred within the walls and vaulted ceilings of St. Clement Danes

When we left the sanctuary and silence of that beautiful church, we came out to a sunny day and a bustling, lively city. London is a proud and, in my opinion, a very happy city. She has endured much over the centuries, and suffered most during Second World War. But she is as alive today as she has ever been... thanks in part to the Royal Air Force. It is fitting then that a church so wounded in the conflagration would rise from the ashes of one of London's worst, yet defining, moments and become the vessel into which much of the sadness was poured. I have seen and heard how people who suffer great personal loss need closure - a part of that lost person, a memorial, a place to grieve, to come to terms with the reality of the loss so that life may resume and the sun can shine. St Clement Danes represents closure for a city, a nation, a commonwealth and its alliances and for those who visit.. an individual. The rebirth of St. Clement Danes represents a moment of spectacular creativity by the Royal Air Force, one for which I offer thanks from Vintage Wings of Canada.

I'm not going back to church on a regular basis anytime soon to be perfectly honest, but I thank the RAF of all people, for a glimpse at what faith must be like. Me... I will put my faith in the strength of our heroes, armed forces, first responders, hard workers, volunteers, givers, team players and history makers - so many of whom hold faith in a God I have yet to find.

By Dave O'Malley

Just hours after running this story, we had the following response from former RAF fighter pilot Desmond Peters. Witnessing the raid that night, he would come full circle in a few years to fly Spitfires for his hometown squadron.

“For those that were there at that time, as I was at 16 years of age, and to witness the destruction of that raid, it was very sad to see that such beauty could be damaged or destroyed the way it was. In London, there were two heavy raids that were spoken about during the war; the Wednesday night raid and the Saturday night raid. The latter was the May 10 1941 raid ( when St.Clement Danes was bombed) and was concentrated on the City of London, the square mile financial district. I lived about five miles to the west and we had a stick of incendiary bombs fall on the street in which I lived, presumably by a crew that we a little off course. In fact, one was alight one metre from our front door but was quickly put out with a sandbag. Another incendiary landed in a factory about one hundred metres up the street and was blazing well. A man and myself kicked in the factory door and, with a stirrup pump, put out the fire by spraying water on the bomb. We were just in time and not much damage was done to the building.

The next day, I watched a Dornier Do.17 shot down and the four man crew bail out by parachute. We all cheered at this, partly at the success of the fighter and, I guess, partly in a spirit of revenge for what had happened the previous day in the City.

In those days, any red blooded boy wanted to be a Spitfire fighter pilot as we were enthralled at the exloits of the RAF. I succeded a bit later by flying Spits for about 250 hours with 600 Squadron ....which happened to be the "City of London" squadron.”

The soaring ceiling and altar of St. Clement Danes with unit colours draped from the gallery. Photo by "stiffleaf" on Flickr

High above the altar is this ornately carved coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth II, who opened the church to great fanfare in 1958. The Latin inscription below the crest is translated as "Built by Christopher Wren 1681. Destroyed by the thunderbolts of air warfare 1941. Restored by the Royal Air Force 1958" Photo by "stiffleaf" on Flickr

A view looking down the length of the central aisle from the communion rail to the front doors of St. Clement Danes. Above the entrance towers the spectacular pipe organ. The church resonates with rich detail, polished wood and the carved Welsh slate crests of all the squadrons and units of the RAF, RCAF, RNZAF, RAAF and others. On the lit pillars are sconces decorated with the crests of RAF Commands. Walking down this aisle, visitors are acutely aware that they are trodding on history and holy ground. The restoration work was done in the 1950s, but crests in the floor are still being installed and dedicated in ceremonies today. The author's first knowledge of St. Clement Danes came after watching a video of a dedication ceremony for the crest of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. Photo by Ian Hadingham

A close up of the elegant inlay of marble and brass for the Royal Ceylon (Sri Lanka) Air Force. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Another close up - this of the Royal Canadian Air Force crest - in red and blue marble, white Welsh slate and with brass delineation. Photo by Dave O'Malley

The entire floor is covered with bronze squadron crest and many individual inlaid memorials such as this gorgeous one dedicated to the 16 brave, romantic and highly successful squadrons of the RAF that participated in the Battle of Britain or the Second World War. The symbol found at the right in the top bar of four is that of the very famous 303 “Kościuszko” Squadron - the highest scoring squadron of the Battle of Britain. One of 303's Flight Commanders during the battle was Canadian Johnny Kent, DFC and Bar, who would go on to lead an entire wing of 4 Polish squadrons. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Perhaps the single most striking feature of the church is its floor - covered with nearly 1,000 carved Welsh slate plaques for each of the RAF commands, groups, stations, squadrons (of the Commonwealth air forces) and other formations. The author took the time to capture a few of them - here the very Canadian 434 Bluenose Squadron crest on the left and the crest of 441 Silver Fox Squadron on the right. Vintage Wings of Canada friend and former 441 Squadron pilot tells us: 441 was based in Europe throughout the Cold War, flying Sabres initially, then CF104s and finally the CF18. In the seventies, squadron CF104 pilot Jim Gale came upon St Clement Danes while exploring London and made it his personal project to have the Silver Fox crest added to the collection. So, on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, the 30th of April 1978, there we were for the dedication ceremony, most of the squadron pilots accompanied by our wives, flown from CFB Baden-Soellingen in an air force Cosmo. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Some crest have been worn down over the past 50 years. The author did search for and find the crest of a somewhat forgotten 131 Squadron in which Ottawa native David Francis Gaston Rouleau served for the better part of a year before being killed in action near Malta. For more on the story behind this Canadian and Ottawa hero click here. Photo by Dave O'Malley

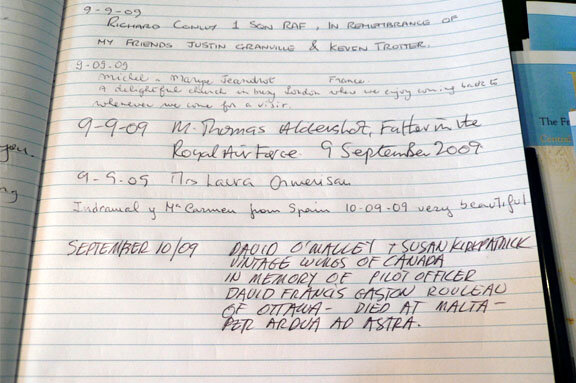

A guest book sits at the entrance. Upon leaving, the author wrote a note of remembrance for the fallen Pilot Officer David Rouleau of Ottawa. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Carved memorial panels line the walls. This largest of the panels describes the beginnings of the Royal Air Force and lists the absolutely incredible battle honours of this storied service. Photo by Dave O'Malley

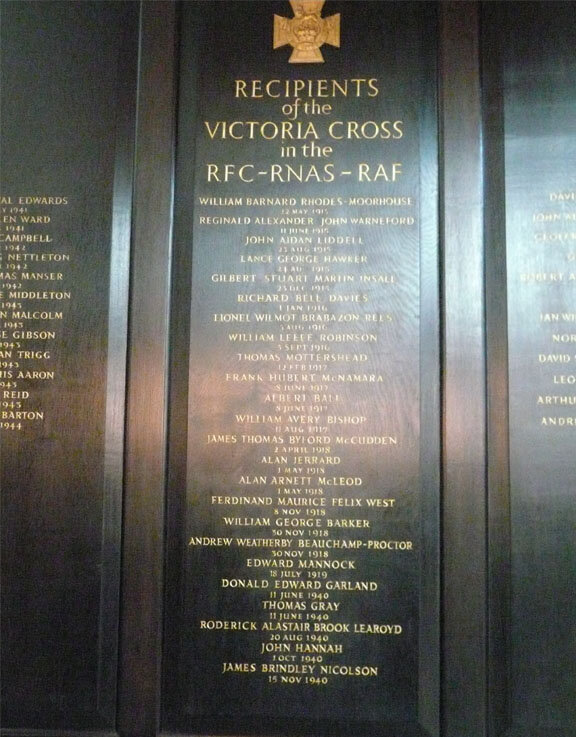

Elegantly carved and gold-leafed wood panels are found throughout - dedicated to the glories of military fliers. Here we see the panel honouring airmen who were Victoria cross winners of the First World War. This list includes Billy Bishop of Owen Sound, Ontario and William Barker of Dauphin, Manitoba. other panels include the names of Canadians David Hornell, Andrew Mynarski, and Ian Bazalgette Photo by Dave O'Malley

Another carved panel includes the name of another Manitoban, Andrew Mynasrki who was awarded his Victoria Cross posthumously in 1946. Mynarski was 27 years old and flew with 419 "Moose" Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War when he gave his life attempting to help rescue a trapped crew member. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Spectacular carvings abound at St. Clement Danes. The back of pews reserved for high ranking officers display intricately carved eagles - a fitting symbol for warriors that rule the skies. Photo by "stiffleaf" on Flickr.

The seemingly endless pantheon of squadron and unit crest speaks to the sheer immensity of the wartime efforts of the RAF and her sister air forces. Photo by Dave O'Malley

The soaring pipe organ of St. Clement Danes was a gift of the United Sates Air Force. The central bass pipes reach upwards from two eagles to be surmounted by yet another eagle. Everywhere, there are details that serve to remind visitors that this is the RAF's church. The organ which stands in the gallery was designed by Ralph Downes and is reputedly one of the best in London. It replaced the organ by Father Smith, destroyed in 1941. Photo by Charles Dastodd

Along both sides of the church are shrines (blue windows) containing the books of remembrance, in which are inscribed the names of those men and women who have died on active service with the Royal Air Force and others. Photo by Treble2309 on Flickr

Along the outer walls of the church are alcove shrines featuring books of remembrance that include the names of more than 125,000 men and women who have died in the service of the RAF and other Commonwealth air forces. The first book predates the RAF and has names of balloonists who served with the Royal Engineers, members of the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps and RAF personnel up to the outbreak of the Second World War. Books II to IX contain the names of all those died on service during the Second World War including this two-page spread featuring RCAF navigator Donald Elliot, a Swift Current, Saskatchewan native. The pages are turned daily, so it will be many months before Elliot's story can be read by visitors again. There is a tenth book which includes the names from VJ Day to the present - it is updated twice a year.

Those who die in service are remembered shortly after their death during a celebration of the Holy Communion and family members are often present. Once a year in November a memorial service is held for all those who have died during the past year and families are invited to attend. This is a most moving occasion and has helped many people in their grief. It is these books and the names within them that people come across the world to see, making St Clement Danes truly a place of pilgrimage and remembrance. Photo by Dave O'Malley

As with the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, family members feel the need to leave mementos and notes to their lost ones. Here a card is left by the still grieving family of two lost brothers from the Second World War- a poignant and touching reminder that the scars are still fresh 70 year on. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Everywhere one looks in the church, there are details that sing of the RAF and the business of flying and fighting Britain's wars - even the kneeling pads. Throughout the church are hundreds of custom crocheted knee pads hanging from the pew backs - most with the same palette of colours. The author could not help wondering which "ace" knelt here in prayer, thinking of his fallen friends. Photo by Dave O'Malley

In some pews and tables, visitors have left heart wrenching crosses and notes to their loved ones who died in the service - many after the wars. Photo by Dave O'Malley

Around every corner and in every niche of the church visitors will find commemorations and monuments of sorts to the greatest heroes of the Royal and commonwealth Air Forces. Here we see a chair dedicated to Sir Archibald McIndoe CBE FRCS (4 May 1900 — 11 April 1960) was a pioneering New Zealand plastic surgeon who worked for the Royal Air Force during World War II. The work done by McIndoe in both physically and psychologically rehabilitating badly burned aircrew earned him an international reputation. McIndoe fought to improve the pay and conditions of badly injured airmen and 'The Guinea Pig Club' of his ex-patients perpetuates his memory. Photo by "mcaballe" on Flickr

No matter where you look, you will see tributes hiding behind pews, in corners or as part of the furniture. Here, a cabinet holding knee pads is a tribute to Group Captain "Sailor" Malan, who for obvious reasons did not like going by his given name Adolph. Adolph Gysbert Malan DSO & Bar DFC (24 March 1910 – 17 September 1963), better known as Sailor Malan, was a famed South African World War II RAF fighter pilot who led No. 74 Squadron RAF during the height of the Battle of Britain. Under his leadership 74 became one of the RAF's best units. Malan scored 27 kills, seven shared destroyed, three probably destroyed and 16 damaged. Malan survived the war - to become involved in the anti-apartheid movement in his country. One wonders what relationship "An Englishwoman" had with the dashing Malan that she would create this memorial. Photo by Dave O'Malley

It's not just men in uniform who are honoured inside the walls of St. Clement Danes. Reginald Joseph (R.J.). Mitchell, the aeronautical engineer credited with the design of the Supermarine Spitfire is canonized for his incredible contribution. Photo by Dave O'Malley

The reverse of the Mitchell plaque - a relief in silver of a Spitfire overflying Mitchell's Schneider trophy-winning Supermarine S.6B - considered the progenitor of the greatest aircraft ever designed in Britain - the Spit. Photo by Dave O'Malley

An ornate and winding staircase descends into the church's crypt where more tributes are found as well as the relics of older churches that stood on this site. Photo: Chris Bennett, St Albans UK

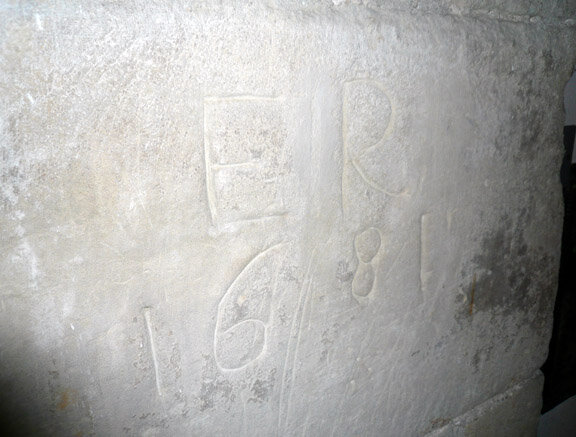

There were two Queen Elizabeths. Queen Elizabeth I died just 6 decades before Wren's masterpiece was completed. The original building was opened in 1682, so this scratching on the wall of the crypt possibly was done by one of the men who worked on the construction. Queen Elizabeth II presided over its reincarnation as the RAF Central Church and her symbols can be seen on the vaulted ceiling of the chancel above the altar.

Down in the crypt, there are many artifacts of the previous incarnations of the church, but as well there are a number of small and more humble memorials. This simple display on an easel pays honour to Dermot McKavanagh, an RAF padre who risked his life to talk a suicidal airman out of ejecting himself from a fighter inside a hangar. At great risk to themselves, chaplains in the RAF and other services have followed their flock around the world and into battle zones - all without the protection of a personal weapon. Photo by Dave O'Malley

The RAF forgets no one. A bronze pays tribute to the men and women from the occupied countries who risked and sometimes suffered imprisonment, torture and death to rescue, harbour and return Allied airmen during the Second World War. The placement of this plaque on the walls of the crypt seems apt, as so many airmen were hidden from the enemy in such places. Photo by Dave O'Malley

St. Clement Danes is still a target of bombers today. On the 90th anniversary of the formation of the RAF in 2008, a Lancaster bomber flanked by Spitfires and Hurricanes of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (an official unit of the RAF), fly down the Strand and over St. Clement Danes. Photo via the RAF and St. Clement Danes

On the 90th anniversary of the RAF, the Red Arrows lead four Typhoon II Eurofighters in formation low over the church. Photo via the RAF and St. Clement Danes