First Flights of Ottawa — Episode One

Every town in the world has, in its recorded history, a particular day when the first puffing steam train arrived, when electricity first illuminated one of its streets, when a motorcar first appeared to scare the livestock, or when the first wobbly flight was made in that last of frontiers — the sky above. The early decades of the history of aviation ended a century ago. Many of the events and milestones in those early and dangerous years took place in rough landing fields on the outskirts of towns and cities around the world but most frequently in North America and Europe. In that hundred years these cities have grown and spread and the green fields of history have long ago been built upon. Rarely will you find an early landing field today that remains so.

The first rail service in Ottawa (then called Bytown), the Bytown and Prescott Railway, commenced service in 1854. In 1855, Bytown changed its name to Ottawa and became the first city in the world to light all of its streets with electricity. The first motorcar in the city was, of all things, an electric car — driven down the horse-manure soiled the streets of Ottawa by industrialist Thomas Ahearn on September 11, 1899. Finally, and more of interest to aviation history enthusiasts like us, the first heavier-than-air and powered aircraft, a lumbering red and yellow contraption called the “Red Devil” lifted off in 1911 from a bumpy pasture along the banks of the Rideau River called Slattery’s Field — named for the well-to-do Irish farming family who grazed their sheep and other livestock there. Slattery’s Field — not the same as Roosevelt Field, Floyd Bennett Field or Boeing Field, but named such because it was, well… a field. With cows. And sheep. But that’s for Episode Two

This story may not pique the interest of folks in far away places, but for my colleagues, fellow aviation buffs and neighbourhood friends, it’s a story worth putting down. It has been 110 years since that first powered flight in Ottawa and it’s time to fill out the story as best I can.

The story of Ottawa’s flying machine history starts long before that long-awaited lift-off from Slattery’s Field. We have to go back to 1858 to find the first attempt to ascend into the sky, but this would not be an aeroplane, but rather a gas-filled balloon.

1858 — The City’s First Aeronaut

Even before Canada was a country, the people of Ottawa welcomed aeronautical adventurers. The first man to ascend into the sky above Ottawa was an American by the name of Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe, or as he liked to be called in later years: “Professor Lowe”. We will soon see that performance balloonists throughout the early years of the “science” loved to call themselves “Professor”. Perhaps it leant an air of gravity and scientific pursuit to counterbalance the circus-like atmosphere that surrounded such events. According to Robert McNamara of ThoughtCo.com,

“In the 1850s, when Lowe was in his 20s, he became a traveling lecturer, calling himself Professor Lowe. He would speak about chemistry and ballooning, and he began building balloons and giving exhibitions of their ascents. Turning into something of a showman, Lowe would take paying customers aloft.”

In his role as a carnival performer, Lowe acquired his first and previously used balloon in 1858 and brought it to Ottawa. Here, as part of Victoria Day celebrations of that year, he intended to make this city’s first balloon ascent (and likely his own). During his appearances in Ottawa, however, he went by another and very curious name: Monsieur Carlincourt, the Great European Magician. It seems balloonists and early aviators also liked to use exotic pseudonyms, stage names or even aliases.

Since I had no access to Ottawa newspapers for 1858, I searched Montreal papers for information about his Victoria Day ascension attempt, finding, at first, this small bit in the Gazette in mid-May, 1858

“We understand that a large subscription has been got up for the purpose of celebrating Her Majesty’s birthday [Queen Victoria] in this city, in a becoming manner. It is intended to have a grand balloon ascension, and we are informed that Monsieur Carlincourt has gone to New York to make the necessary arrangements, etc.”

Two weeks after that note in the Montreal Gazette, there was a follow-up story about the Victoria Day festivities in Ottawa on the 28th of May, 1858.

The grand balloon ascension had been announced to take place at 3 o’clock from the lumber yard of Aumont and Turgeon, in the Lower Town. The doors were to have been open at 1 o’clock, and 25 cents a head was to have been charged for admission, but till 3 the impatient crowd was kept outside. All at once the big gate was thrown open, and in rushed the throng without paying the quarter or being asked for it. Here, upon a high stage, the Great Aeronaut, Mons. Carlincourt, stood and beckoned to the people to listen to him. He then stated, in the most bland and polished way, that “the cause why the balloon did not go up was for the reason that they could not get enough gas to fill it.” An American Brass Band that he had with him then struck up and played for a while, after which he announced that he would take the balloon to the Gas-works and try to fill it there. Accordingly the scene of operations was transferred to the middle of Rideau Street [the main east-west artery at the time - Ed], where the gas pipe was opened and the process of filling commenced, the military keeping off the people and the bands of music playing in turn. It seemed to take an unconscionably long time to fill it up; but at last, after three hours had passed, the big bag stood up the height of a two-storey house. All were on the tip-toe of expectation, when, lo! by an unlucky gust of wind it swayed over on a lamp-post, and a great rip was made in it. All was now lost.

Poor Carlincourt had enough to do to keep himself and his balloon from being eaten up by the mob, many of them swearing it was a Yankee humbug. Certainly the balloon itself appeared to have past [sic] its better day: it was patched in various places, and the smell around it indicated it was leaking gas out somewhere. It is said that the Aeronaut intends to try again in a week to ascend in a new balloon. Others say he has cut stick this morning, and will not be seen here again. Perhaps the latter contingency is the most probable.

A great performance had been announced by the same individual to take place in the Theatre, but what it was to be no one knew. The Theatre, however, remained closed all evening. Probably the Magician was so exhausted by his aerial ascension as not to be feel able to interest an audience.

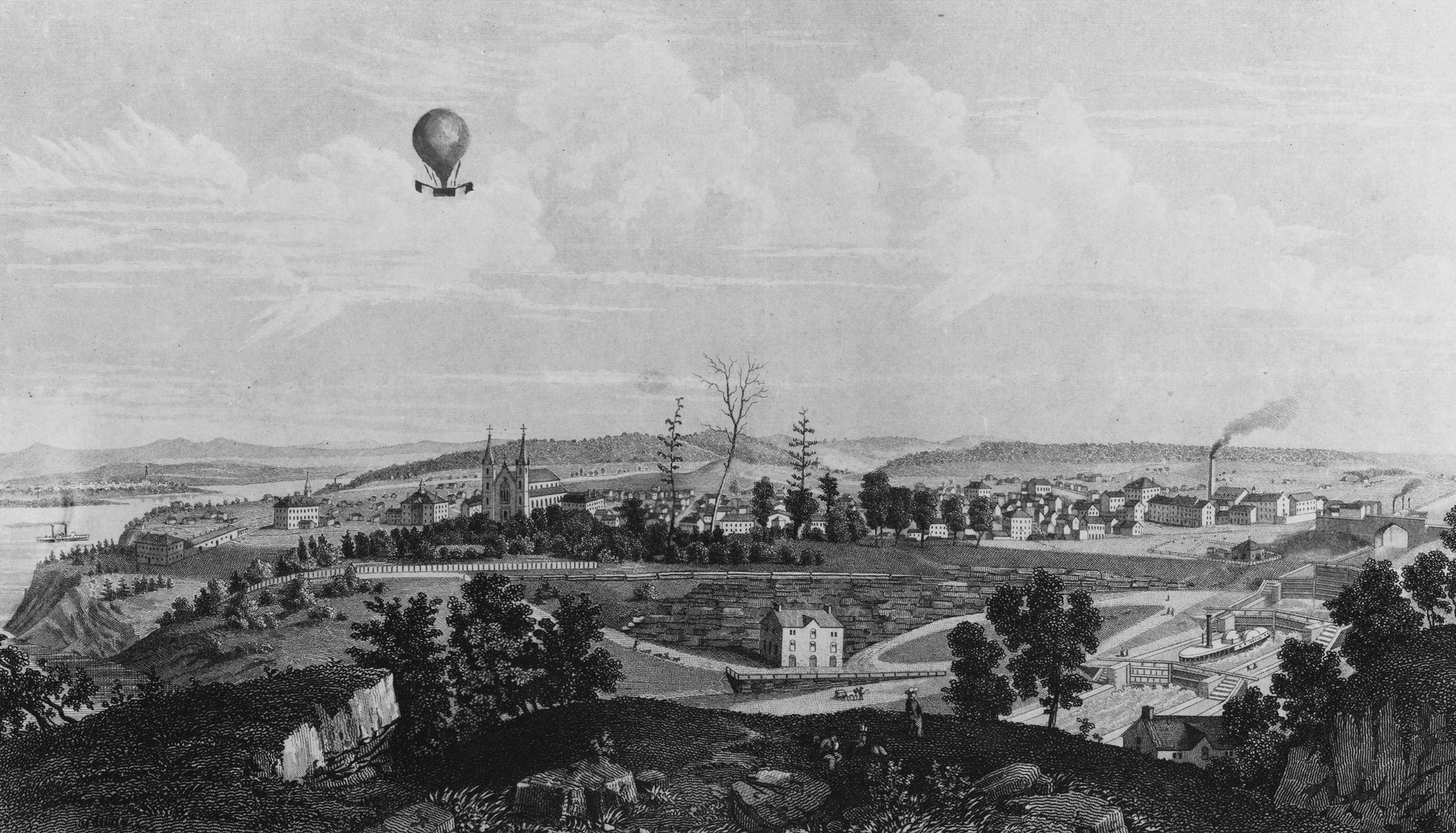

Regardless of his Ottawa failure in May, Professor Lowe (or Monsieur Carlincourt or Thaddeus Lowe or whomever) was back in town a couple of weeks later with a new balloon and staged the first successful aerial ascent in Ottawa on June 17. The balloon rose from Major’s Hill, across from today’s American Embassy. Lowe was the first human being to see Ottawa from the air. He remained in Ottawa and on September 1st, made another ascent, apparently in honour of the laying of the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable.

According to the Bytown Museum, this print was based on Edwin Whitefield’s original lithograph, “Ottawa City, Canada West” from 1855, with Lowe’s balloon being added by Charles Magnus & Co., of New York to commemorate the ascension. In the foreground stands Major’s Hill where Lowe lifted off. To the right we can see the terminus locks of the Rideau Canal and tucked in just below that is the roof of the British Army Commissary, present day home of the Bytown Museum.

Lowe shortly became one of the most forceful voices for ballooning, especially as a reconnaissance technology for military purposes. After nearly being caught for spying following a trip in 1860 over what would become Confederate territory, he took his ideas for the martial use of flying machines to the US Army. On 26 June 1861, the US Army Corps of Topographical Engineers adopted the balloon for the Army Service. Lowe was given the title Aeronaut, Commanding Balloon Department, Army of the Potomac. He organized and trained the Aeronautic Corps for the Balloon Corps of the Army of the Potomac, which became an official branch on 22 December 1861. Though the Balloon Corps did not last longer than the war, and much of its gained intelligence was squandered, Thaddeus was in fact the first military aviator in American history.

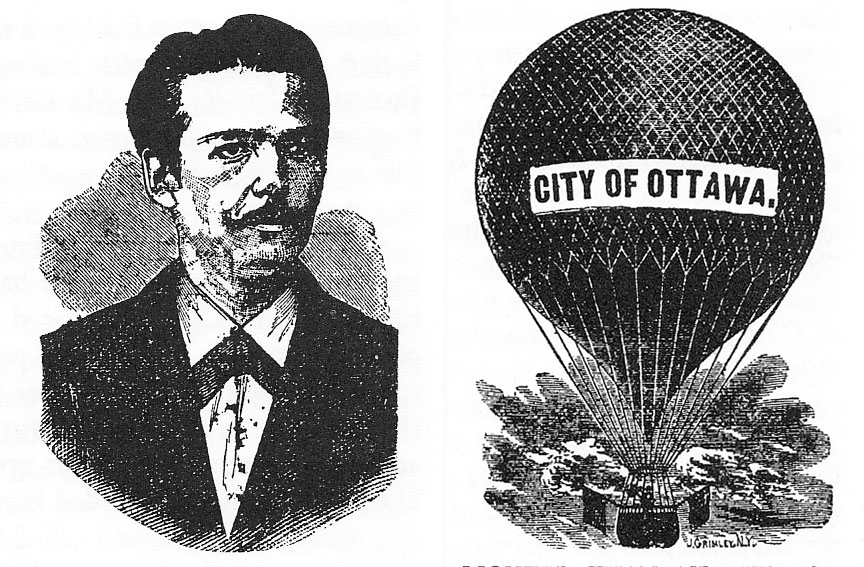

Left: “Professor” Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe, AKA Monsieur Carlincourt, the Great European Magician. Right: Though Lowe was pathetically equipped in his first commercial adventure in Canada’s capital in 1958, three years later at the outset of the American Civil War he was far better equipped for a demonstration in Washington — gas wagons, large hoses, support wagons and commandeered American soldiers. Note that the US Capitol Building is still under construction 68 years after the laying of the cornerstone. Construction was stopped during the Civil War. Photos via the Galactic Gazette

Lowe’s greatest dream was to make a balloon crossing of the Atlantic Ocean from America to Great Britain, a feat that he would never come close to achieving. Balloon technology and weather forecasting would not be good enough to achieve this for more than 100 years. In 1978, 120 years after Professor Lowe’s first balloon flight, three men in a helium balloon called Double Eagle II finally made the crossing.

If you ever wondered if these huckster “Professors” ever made anything from their efforts, travels and risks, this is Thaddeus Lowe’s home in Pasedena, CA, replete with its own observatory. Photo: Pasedena Digital History on Flickr

Over the next years, the Citizen ran many stories on Professor Lowe’s military balloons in the service of the Union Army, but there was little aeronautical activity in the region. There is mere mention in the Citizen in July, 1868 of a balloon ascent at a large summer picnic event in Hull [now Gatineau], but no details were provided.

In August of 1875, the Citizen reported that a balloon ascent was made as part of a travelling show called Forepaugh's Gigantic Circus and Menagerie. But this type of ascent was more a high wire act than an aeronautical event as the Citizen reported:

“An excited crowd witnessed the balloon ascension in the afternoon. The balloon was inflated with hot air, and reached an altitude of about four or five hundred feet. There was no basket to it, the daring aeronaut being satisfied to risk his life on a trapeze. When the balloon reached its proper elevation he performed some dangerous feats on the trapeze — such as hanging from his toes and swinging around the bar, The balloon sailed away in a north easterly direction and landed the aeronaut on the bank of the Rideau River opposite Mr. Satchell’s residence.”

1877, A Villain Shoots at Professor Grimley

Professor Charles H. Grimley, a self-described “professor” of ballooning in his “smoke”-filled craft called “The City of Worcester” was contracted to provide some thrilling entertainment at the Central Canada Exhibition (CCE) in 1877. The CCE was an annual event held at Lansdowne Park in Ottawa showcasing the economics, agriculture, culture and industry of Eastern Ontario. He had already attempted an ascent in Ottawa in July and was becoming somewhat of a celebrity in Ottawa. Grimley rose from Lansdowne Park at 5:30 on the evening of September 12, and ran in a north easterly direction landing an hour later near Cumberland, Ontario. The last few minutes of his flight were not without incident and the report in the Citizen tells us a lot about how unfamiliar regular folks were with ballooning:

… “About five minutes before landing, and when about 500 feet from terra firma some ignorant fool fired at the balloon with a rifle, the ball passing between car and the balloon about two feet above Mr. Grimley’s head. He shouted to the parties to stop and no more shots were fired. When he cast out his anchor some forty men had congregated together some 200 yards away, afraid to come near the balloon. He called to them repeatedly, and assured them there as no danger, but they doubted his word and refused to come. Finally after some considerable talking, one John Lerian plucked up courage and went to the professor’s assistance. … …When the farmers learned that the balloon had been fired at, great indignation was expressed and a search was instituted for the party who committed the act, but without success,”

1878, A Dominion Day Ascent

On Dominion Day, 1878, [Now called Canada Day] Professor Grimley was back with his balloon in Ottawa. Grimley, an American, was contracted to make an ascent as part of a spectacular schedule of events in Ottawa that included tight rope walkers [“Professor” Jenkins walking], a quarter-mile foot race for amateurs, a Fire Department parade, a 21-gun salute from the Ottawa Field Battery, athletics at Cartier Square drill field, a baseball game between Kemptville and Ottawas Dauntless Sports Club for a $75 prize and of course a fireworks display. Grimley let go the lines in the afternoon, carrying along a passenger by the name of George Fox, and the balloon “floated off splendidly, amid the cheers of the assembled multitude.”

A few days after his successful ascent above Ottawa, it was announced in the Ottawa Citizen that he had been contracted to make another ascent by the St. George’s Society, a local chapter of an English patriotic society established to encourage interest in the English way of life. The balloon flight was scheduled for the society’s annual picnic on August 27. Grimley returned to Ottawa two weeks before the picnic, with a brand new balloon, busying himself by putting the name CITY OF OTTAWA on it and getting it ready for the flight. The balloon was taken to Cartier Square where it was filled from a gas company line. Thus inflated, it was “towed” to Lansdowne Park [a distance of two miles] “by way of the canal”. I am not sure if that means it was walked along the edge of the canal, or placed on a barge and towed down the waterway]. Regardless, Grimley arrived “amid the ringing cheers of the immense crowd of people…”.

After a series of tethered ascents with dignitaries [Including lucky Mr. George Fox again] Grimley and a member of the Ottawa Citizen staff, Mr. W. Gibbens, whose report of the voyage very nearly filled the front page of the Citizen the next day, rose from Lansdowne above the cheering throng and moved slowly eastward. Gibbens, in his report, exuberantly wrote:

“The passage through the cloud was perhaps the most striking feature of the ascent; although the view presented to our gaze on emerging from it above, with the dazzling rays of the sun playing upon the snow white and mountainous shape of the immense mass of vapour, was one of the most gorgeous spectacles that has ever been the lot of your representative to witness.”

Professor Charles H. Grimley and his balloon, the City of Ottawa. The caption beneath his portrait read “AUDACIOUS PROFESSOR: Charles H. Grimley was a “professor” of the art of ballooning. He had been nearly frozen, nearly drowned, nearly asphyxiated, nearly battered to death. But he still pursued his profession with undiminished zest. A fascinating man, ladies were not adverse to going aloft with him in his balloon, so long as a rope anchored it to earth.

At 5:55 pm, Gibbens released a pigeon. They were three miles from Lansdowne Park and at 6,250 feet. The note he sent with the homing pigeon read in part:

“Heard two heavy peals of thunder shortly after leaving grounds [Lansdowne], but the Professor says it is alright, and we shall go ahead. Bush fires burning in different sections. Mist prevents minute observations. Gibbens.”

The flight which, for much of its passage, had been so sublime, very nearly ended in disaster when, in failing light, they were drifting towards the vast and trackless bog to the east of Ottawa known as the Mer Bleu. Desperate not to come down in a watery bog miles from help, they chose to descend immediately selecting a clearing which from 3/4 of a mile away looked open and dry. Nearing the spot, the realized it was in fact watery and dangerous. Committed to coming down now, they both grabbed on to a passing branch:

“There was nothing for it now but to land in the trees., and coming down to within a few feet of the topmost branches we caught hold of an old rampike which stood out above the rest, being nearly sixty feet high. To this we clung for a few minutes, the balloon standing beautifully still above us, in the dead calm which reigned.”

The story of Grimley’s ascent from Lansdowne Park along with Citizen reporter Gibbens covered the entire front page of the next day’s paper. Image via Newspapers.com

In a scene from a stereo-view card, Grimley inflates a similar balloon at Montpelier, Vermont a few years later. Image via The Barre Montpelier Time Argus

The Professor and Gibbens were rescued by locals and led out of the treacherous Mer Bleu after dark and treated to a “good substantial supper, which we [devoured] with the appetites of back-woodsmen.” They were driven back to the city after dinner and made plans to retrieve the balloon in the following days. The pigeon released during the flight arrived the next morning.

Balloon ascensions, as they were widely known, had become a staple at civic holidays and fairs across the country and in the region. Grimley’s successes in Ottawa would bring him back to the Exhibition again in 1880 and a “Miss Carlotta” made a 1883 Dominion Day ascension, filling her balloon at Cartier Square declaring that the gas from the Ottawa city gas works was “the best she ever used”. The balloon, like Grimley’s was transported by canal barge to Lansdowne Park and by all accounts “considerable difficulty was experienced in getting it there..” She rose to a height of two miles as she drifted out of sight to the southeast. She would eventually land in a copse of trees near Carlsbad Springs [then known as Eastman Springs - Ed.] where her balloon was shredded and rendered unusable. She returned by train. As far as I can tell, Miss Carlotta was the first woman to solo in the skies over Ottawa.

Miss Carlotta, “The Lady Aeronaut” (left) was a stage name. Her real name was Mary Myers, born Mary Breed Hawley in Boston Massachusetts. Along with her husband she set up a successful business of making and selling hydrogen balloons from their five-acre farm (right) in Frankfort, New York which was known as the Balloon Farm. Her husband, unlike most balloon “professors” was an actual scientist and aeronautical engineer and they both had many patents for ballooning and helped perfect the science. Images Wikipedia

In 1884, an aeronaut couple made appearances at the Exhibition in September — Professor and Madame Lowanda. They made several balloon ascents together during the exhibition, and “sent down perfect showers of cards and handbills containing advertisements of some of the businesses represented at the Exhibition”. In addition to his aeronautical skills, Professor Lowanda was also a magician, ventriloquist and dog-and-pony specialist. Madame Lowanda was also a mind-reader. They came from a family of circus performers. On Saturday September 27, Madame Lowanda, the so-called Queen of the Air, made her first solo flight over Ottawa, flying off to the northeast and coming down near Templeton, Quebec, across the river from today’s Beacon Hill neighbourhood.

1888 — Nightmare on Bank Street

In 1888, the Central Canada Exhibition’s organizers brought another hot air balloonist to the exhibition — “the greatest out-door wonder the world has ever witnessed.” boasted the CCEA. The balloonist, a Professor C. W. Williams was to rise in his balloon to a height of one mile and then, with the aid of a parachute, jump from it in front of the crowd. Sadly, on September 27th, one of the young volunteers holding the ropes and skirt of the balloon securely on the ground until ready failed to let go as the ship rose from in front of the Grandstand. Despite Williams imploring 21-year old Thomas Wensley to jump early in the ascent, he held on until he no longer could, and plummeted to his death, dropping into a Glebe backyard near where Mutchmor Public School is today. As reported in the Cincinnati Enquirer, “down he came like a rocket, executing a series of somersaults in the air. He struck in a field one hundred feet from the grounds, and, with the exception of his face, was terribly crushed.” Williams did in fact make is descent by parachute and collect his $700.00 fee.

The next day’s headline read:

HORRIBLE TRAGEDY

A Human Being Drops from the Clouds in Mid-Air

THOUSANDS PALE AT THE SIGHT

It was Canada’s first aerial-related death and Thomas Wensley is buried at Beechwood Cemetery. Despite the horrors that had happened that day, CCEA organizers knew a good crowd draw when they saw one. Circus-like acts that featured aeronautical feats, new-fangled “technology” with a possibility of a disastrous outcome and daredevil aeronauts who called them selves Professors were drawing crowds around the world.

1904 — Professor and Mrs. Balloonist

In 1904, the Central Canada Exhibition featured the exciting husband and wife balloonist-parachutist act for the daily Grandstand show — Professor Edmund Rayne Hutchison and his wifey from Elmira, New York. They made all their ascents safely in a hot-air balloon, then leapt from the gondola with a parachute, leaving the balloon to cool down and descend on its own. The Ottawa Journal reported:

“Prof. Hutcheson [sic] and Mrs. Hutcheson made one of the best exhibitions of a double balloon ascension and parachute drop yesterday afternoon. The lady dropped first, while the professor hung on to the balloon until it was nearly out of sight, and the thousands watching him thought that something must have gone wrong with the intricate paraphernalia and the professor might never come down. At last, however, the parachute was seen making a most graceful drop, and the professor came slowly to the ground several miles from the city. Another thing that puzzled the spectators was the fact that as the ascent was made both lady and gentleman were seen to be most busy distributing something that landed on the Exhibition grounds several hundred feet from earth. These were the celebrated snowshoe tags which the Bob’s Plug Tobacco Company have on hand for all those who patronize this splendid brand of tobacco..”

Prof. Hutchison was clearly engaged in a side-hustle that day for Bob’s Plug Tobacco and the Ottawa Journal effused in support of the tobacco exhibitor:

Bob’s Plug Chewing Tobacco Exhibit

No single exhibit continues to attract such universal attention as that of the Bob’s Plug Chewing Tobacco, which is surrounded the day long by an eager throng anxious to testify to the merits of this famous chewing tobacco and to hear how they may, by the return of the celebrated Snowshoe tags, procure valuable premiums…

Mrs Hutchison, when interviewed by the Ottawa Journal, had this to say about the most important qualification for being an aeronaut:

““An aeronaut,” she said “must possess the infinite capacity for taking pains. That is the most important qualification. Then of course he must have a level head and a strong will power. I was taught all I know about ballooning from my husband, who has been in the business for seventeen years, and is known as the most careful aeronaut in America.”

Despite the Hutchison’s infinite capacity for taking pains, he ran into a little trouble with his balloon a few days later, as reported in the Citizen:

… Professor Hutchison’s balloon met with a slight accident. The huge gas bag had not been balanced properly and after its occupant had vacated his perilous position within the bomb the balloon failed to swing round and soared for miles along the Ottawa River. The mishap was caused by one of the sand bags dropping before the aeronaut descended.”

After Hutchison parachuted from his balloon, it drifted north on the wind, finally coming down on the rifle range near Rockcliffe where soldiers secured it. However, the soldiers would not hand over the balloon to Mr. Willis, Hutchison’s assistant, who had been flight-following the balloon in an automobile, unless he gave them $5.00, which he refused to do. The issue was at an impasse until the Central Canada Exhibition Association stepped in and retrieved the ransomed balloon for Hutchison.

From this drawing in the Ottawa Journal of September 22, 1904,, it appears that Hutchison and his wife were suspended beneath a deployed-but-not-inflated parachute rig which was attached to the balloon, from which they would cut away, Note the smoke from the wood fire used to make hot air for the balloon.

1909 — The beginnings of a failure

Though Ottawa would not see an actual heavier-than-air flying aircraft until the late summer of 1911, that didn’t mean people in Ottawa were apathetic towards the new world of flight. In July of 1909, the same year of Canada’s first powered, controlled and heavier-than-air flight at Baddeck, Nova Scotia, a “German” citizen, by the name of George Lohner arrived in Ottawa and managed, through his flimflammery, to secure funding from a syndicate of local businessmen to build a powered, heavier-than-air flying machine — better than McCurdy’s Silver Dart according its inventor. The Ottawa Citizen for July 19, 1909 reported:

“Ottawa may shortly be the scene of some interesting experiments in aviation, if the plans of Mr. Geo. Lohner, a German inventor, who is at present in the city, come to satisfactory head. Mr. Lohner was seen by a Citizen reporter at the New Arlington Hotel, and exhibited a medal which he claims was awarded to him by the Aero Club of Germany. He is not very conversant with the English language, but so far as could be made out he claims to have conceived plans of his own for an aeroplane having advantages over the construction of those used at present. A new feature, he claims, is the manner of distribution of motive power, so as to keep the engines continuously clear, thus enabling long flights. His machine, he also stated, could be traversed across its whole length without interfering with stability. Thus operators would not be confined to a single seat as at present. He carries a small working model on the machine with him. It is probable that he will remain some time in the city.”

A day later, the Ottawa Journal wrote that Lohner:

“HAS BUILT AN AIRSHIP

Claiming to have mastered aviation, Geo. Lohner, a German inventor, at the New Arlington Hotel, Wellington Street, wishes to interest Canadian capital in the manufacture of an aeroplane of his own design which he claims is the most perfect flying machine yet launched. Lohner believes that the manufacture of the aeroplane is shortly to become one of the great commercial features and has parts of his machine patented.”

George Lohner first came to Canada in or just before 1906 and appears in a Canadian Census in Winnipeg in June of that year. He is listed as a boarder at the address he gave. He also gave his age as 31. Then in 1908, his is listed in a manifest of the Canadian Pacific ocean liner SS Montreal on November 15th, 1908, arriving in Canada via Antwerp. He is listed as German as well as a "Returned Canadian", and called himself an engineer. There is no indication on the internet that he was ever awarded any medals for ballooning anywhere or that he had successfully flown before.

The inventor Lohner (inset) claimed to have been born in Munich, Bavaria, to have spent all his life trying to solve the mysteries of the air and to have been awarded numerous medals from the Aero Club of Germany. He also claimed to already have built a flying craft in Germany. Despite the awards and fame he claimed to have, he was not German, but Swiss and was living at one of Ottawa’s low brow lodgings— the New Arlington Hotel, [T. A. Brown Proprietor] where there was a free lunch all day. It seems a free lunch was what Lohner was after. Photo via apt613.ca

What could possibly go wrong?

Lohner managed — by use of his poor English, hand signs and his model — to get funding from a group of local businessmen led by a Dr. Mark G. McElhinney, who in turn used their power to get the city to allow him the use of the Machinery Exhibition Hall at Lansdowne Park to construct his contraption — and a contraption it surely would prove to be. He also stated to reporters that he would have his aircraft built in one month.

An August 11, 1909 story in the Ottawa Journal showed just how much George Lohner had bamboozled local businessmen and newsmen. It quotes Lohner as saying that:

“He will sooner or later manufacture in Ottawa airships in as many numbers as any of the largest automobile factories turn out cars.”

“Lohner is a German aeronaut, and in his time has won many medals in his homeland for his clever feats in making flights in dirigible balloons of his own invention. He has not yet made a flight with his airship in Canada, but says that he has made several flights in the old country”

“My invention will mean a revolution of the aeronautic world” the inventor said. ”

Not quite.

It seems in retrospect that Lohner was in effect building a 60-foot long canvas and oak replica of a paper airplane and his demonstration of a model at the Ottawa Journal offices seems to bear that out:

“Lohner guards his invention very zealously. Yesterday [August 10, 1909 - Ed] he came to The Journal office and wished to insert an article regarding the machine that for twelve years he has been working to perfect. [a little hyperbole was one of his tools - Ed] He carried with him the model of the airship. With a reporter, he retired to a room and there gave a demonstration of the practicability of his machine. The model true enough when thrown dart-like by its inventor, sailed gracefully about the room and settled gradually to the floor. By adjusting wings on the little ship it was made to move upwards in the air or downwards or perform a circle. The model was constructed of steel wire and paper.”

In September of 1909, while attending the Central Canada Exhibition, Lohner witnessed a tragic set of events at Lansdowne Park. One of the featured events at the 1909 Ex was Toledo, Ohio native Tony Nassr, The Daring Syrian, demonstrating flight in his powered dirigible balloon. That morning, the 16th of September, a man assisting Nassr was electrocuted and two others severely burned when his airship contacted wires. He went ahead with the “ascension” and all seemed OK for another flight in the evening. Around 5 o’clock that evening, he rose up into the air and all again seemed well, but shortly thereafter his engine quit and he drifted southeast, releasing gas as he went. The ship came down in a meadow close to Slattery’s farm in Ottawa South. Nassr managed to get the engine working but the propeller was damaged when it caught in a guy rope and the ascent had to be abandoned. He recruited several men to help him carry the lighter-than-air ship up Bank Street, over the canal and in through the south gate of Lansdowne Park, the gas bag again became entangled in electrical wires overhead. The rubberized silk-covered gas bag caught on fire, and Nassr, fearing a repeat of the mornings fatal events, shouted to his assistants to let go the lines. The burning hydrogen resulted in a rapid ascension of the unmanned and flaming dirigible. At a great height, the gas bag finally exploded and the whole rig fell in flames onto homes on Aylmer Avenue in Ottawa South where watchful locals put out the flames. Lohner told the Ottawa Journal “This is simply an example that the dirigible balloon will never be of any use in commerce or in war. It is too bulky and too delicate.” He offered no sympathy for the man who was killed or those burned. Nassr survived his harrowing vocation to become Balloon Inspector for Goodyear in 1919 and the Director of the Toledo Airport on 1927.

By October, the Journal reported that Lohner claimed:

“ … he will celebrate Christmas by sailing in his machine from the Exhibition Grounds over the Parliament Buildings to Gatineau Point and back. [A distance of about 20 kilometers-Ed]. Lohner says that in doing this feat he will carry with him several passengers. He is getting on well with his work on the machine and now has the frame completed.”

By late November, Lohner was no longer living at the shabby New Arlington Hotel and now slept and ate in the unheated Machinery Hall at Lansdowne Park, apparently working 18-hour days on his flying machine. Laughably, he told everyone “That the time and place of the first flight was being keep a close secret.”

In February of 1910, Lohner now claimed the first flight would take place on the Ottawa River in March. The Journal reported:

“The early plans of the syndicate backing Lohner to fit the machine with engine and rudders before giving it a trial have been changed [read: the backers were getting suspicious-Ed]. The airship is being set upon three sleighs instead of wheels. On these sleighs the great structure will be hauled to the Ottawa River and at the end of a long tackle will be attached to an automobile. Lohner will take his place in the basket of the airship and will take charge of the steering gear. The automobile will run at a rate of 30 miles an hour. It is the hope of those interested in the invention that the big planes will take the air and that the craft will travel gracefully upon the winds.”

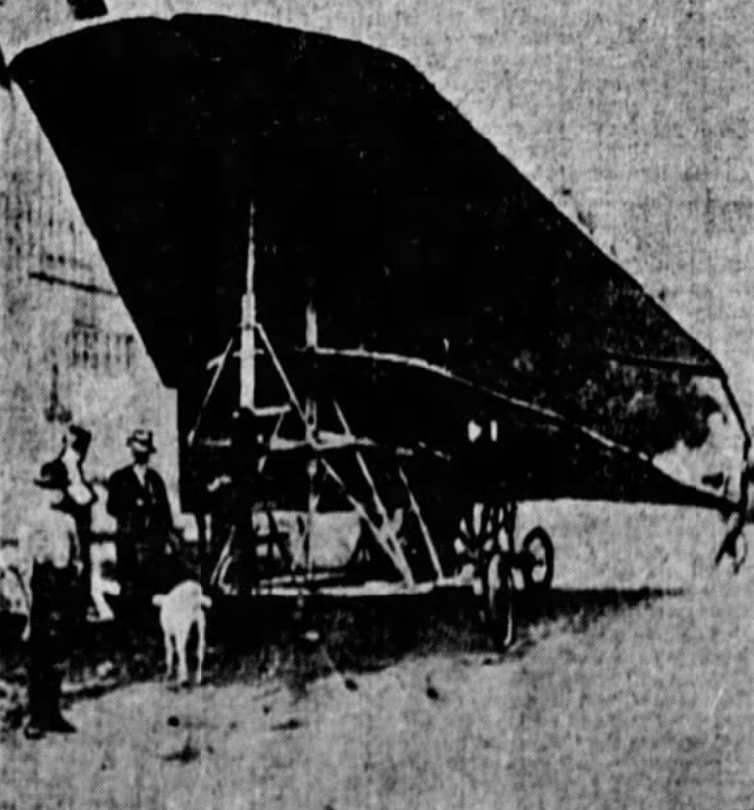

When the machine now dubbed The Lohner No. 1 was first dragged out of the machinery shed at Lansdowne park on a cold and foggy day in March of 1910, it was truly something to behold… unless you knew anything about aeronautical design. Nothing Orville and Wilbur Wright had studied, calculated and quantified for years could be seen in the design — at least not from the comfort of my chair more than a 100 years later. It seems as though Lohner had constructed a 60-foot long paper airplane from oak and heavy oiled canvas. For all its size, it appeared extraordinarily fragile. There did not appear to be an airfoil anywhere on the aircraft.

Some of Lohner’s business associates and assistants pull the huge and ungainly craft on its sled runners out onto the snow next to the racetrack at Lansdowne Park. The Ottawa Journal described the ship as: “..the first aerial craft built in Ottawa. The front portion from which a stick protrudes is known as the controller and is designed for raising and lowering the drome when in the air. There are two big triangular canvas surfaces, set horizontally, the front one being higher than the rear one. The machine is 60 feet long and 20 feet wide, and between ten and fifteen feet in height. The three steel runners on which it is moved over the frozen surface can be seen, and also the circular shaped ones in the rear. ”

Impatient for some sort of publicity and any indication that Lohner’s “aerodrome” could actually fly, the investors forced Lohner to attempt a glide in his craft. On the afternoon of March 12, 1910 with fog still lying over Lansdowne Park, 400-500 Ottawans assembled to catch a glimpse of the craft they had heard so much about. The intention was to tow it behind an automobile on some nearby ice to see if “the drome would rise” before committing to putting an engine on it.

A couple of the investors walked the ice on the nearby Rideau Canal and found it too slushy to drive a heavy car upon and the test was postponed. The Journal went on to describe the details of Lohner’s concoction:

“The Lohner aerodrome is not at all like the McCurdy and Baldwin [the men who flew the actual first flight in Canada the previous year — Ed] type of aerial craft. Two high triangular shaped canvasses furnished resistance to the air by which it is hope to keep it afloat. There are also many devices different to aerodromes that have been tested.”

The Lohner No. 1, with the words THE LOHNER No. 1 OTTAWA, CANADA writ large across it central vane, was pushed back into the shed on March 12, and hauled out again the following Monday. I’ll let the front page Ottawa Citizen report explain what happened next because the story as it is written feels like the script for an episode of the Keystone Cops:

E. H. Code crank starts his car to tow the Lohner No.1 onto the race track at Lansdowne Park in winter conditions. Photo via Kees Kort, Netherlands

LOHNER AIRSHIP CAME TO GRIEF IN STORM AT LANSDOWNE PARK

Machine taken from Shed but runners broke down and the Effort to Haul it over to Race Track ended in Smash. Conditions were Bad and Inventor and Syndicate are Not Discouraged.

Lansdowne Park is an unfortunate place for aerial craft. There was a regular circus, with a little of the pathetic side to it, enacted there this morning when in the blinding snow storm another unsuccessful attempt was made to launch the Lohner airship.

The exciting part of the performance was the effort of the capitalists composing the syndicate backing the inventor to direct the operations, and the pathetic side was the lone figure of the little German aviator [the local papers often referred to Lohner as “the little German. Apparently he was disabled and I sense that this was a dig at his disability — Ed] , who to the last crash kept up his faith in the product of his handiwork.

Determined to have a test, of the soaring capabilities of the huge kite-like machine, a number of members of the syndicate gathered at the shed at 11 o’clock and with the assistance of Lohner took the airship down the four feet step from the floor to terra firma. Trouble began almost immediately.

First, one of the runners under the machine buckled and it canted sharply to the right. Guy ropes were attached and with men at the end of these the machine was righted again. Then the runner on the right side made a figure eight and over the big bulk went again. Ropes were tied to this side and the airship was held upright on the central runner of the three under the machine. This proved stronger than the others and it was then decided to take it out onto the track in front of the grand stand.

The automobile of E. H. Code [a member of the syndicate] was requisitioned and coupled up and with the assistance of the crowd around, the machine was started towards the race track. Everything was going smoothly when suddenly there was a ripping sound from forward, and the whole front plane was torn down the centre by an electric light wire which had not been noticed.

The wind which had been blowing strongly, took on a new lease of life and almost lifted the “airship” off the ground. The men holding the guy ropes were carried hither and thither and confusion reigned. There were shouts at the driver of the automobile to stop, and stop he did with such suddenness that the whole framework lurched heavily to the left and crashed to the ground, carrying Lohner and two of his assistants with it.

They were extricated, happily escaping injury. Mr. Harry Ketchum’s [an automobile dealer in Ottawa] sixty horsepower auto was then attached and the journey to the track commenced anew. With much struggling, pushing and hauling, the immense framework was finally, after contact with a tree on the way, gotten to the entrance gate of the track.

The auto was turned on to the track with the airship in tow. The airship took the grade to the track easily but when it arrived in the gateway stuck fast. A sharp jerk was given and over it went to the left, the whole side breaking over the five-foot fence which surrounds the course. This was the final effort and after a hasty consultation, the decision was reached to forgo the trials and take the airship back to its shed, now about one hundred yards distant.

The turn around was negotiated without further incident, but just as the automobile started pulling, the third and last runner broke in twain. and the whole framework fell to the ground. There it was left for the time being, it being easily seen that any effort to remove it in the face of the storm would be more than useless.

Investors and helpers struggle to keep the Lohner No.1 upright as the wind throws the craft onto its left side while being towed. One wonders why Lohner thought it wise to attempt to test his sail-like contraption in such wintry conditions. Photo via Kees Kort, Netherlands

A model of the Lohner No.1 shows us just how unstable, fragile and ill-conceived the design was. Still, it is an important part of Ottawa aviation history. Photo via Kees Kort, Netherlands

Lohner, still backed by the syndicate of Ottawa businessmen, brought his wreck back to the shed and laboured long through the rest of the winter and spring to repair it and get it ready for another test. He continued to live in the exhibition shed, often without heat or comforts of any kind. In a sad but sympathetic report in the Ottawa Citizen in mid-July we see how much Lohner had suffered for his invention:

“…a Sparks Street merchant said that he had recently found Lohner to be in dire want of the necessities of life and that his family had provided him with food. During the winter, he said, Lohner had nothing more than a small oil stove to keep him warm and with a scant food supply the wonder was how he managed to live under the conditions. “I was very much impressed with the machine which he has constructed,” said The Citizen’s informant, “and I believe we should see him through with his idea. It is the most wonderful case of devotion to inventive genius I have ever seen. Almost any other man would have quit, disheartened months ago.”

Finally, on July 21st, 1910, it was ready for another attempt. This was to be called the Lohner No. 2 [a very apt numerical choice - Ed]. This variant of the Lohner was a wheeled craft. The Ottawa Citizen reported:

“The Lohner airship made a very short flight this morning about 8:30 o’clock, much to the pleasure of the members fo the syndicate… …true, the flight was not much more than a big hop,….

After a preliminary push up and down the road in front of the shed where the machine has been in course of construction, it was decided to attach it to the rear of Mr. Code’s automobile. Taking it over near the horse stables, the auto was attached and the airship given a slow run for a couple hundred yards. Lohner took his place in the seat provided and steered the airship along behind the auto for the distance, everything worked finely and no mishap occurred.

So successful did the first run prove that it was decided to give it another if time permitted, for already a storm was coming up. there was plenty of time and the machine was pushed back again and a fresh start made. This time a speed of ten miles per hour was attained by Mr. Code and as he was going his fastest, the machine rose gracefully a couple of feet from the ground, and the auto slowing down, landed without injury to itself or Lohner, who occupied the aviator’s seat on the second trial.

The little German was immensely pleased… ”

When George Lohner unveiled his Lohner No.2, it was evident that it was quite different from his first attempt, being wider in its flying surfaces and its undercarriage. It had morphed from a giant paper airplane to a giant wheeled kite. The caption accompanying this image in the Ottawa Citizen of July 21 reads: “Front View of Big Machine Which Was Given Successful Soaring Test The Morning” Clearly soaring was an exaggeration. Image: Newspapers.com

The Windsor Star devoted a column-inch to Lohner’s achievement which in a few words summed up Lohner’s experience”:

“George, Lohner, almost penniless, but confident that he had constructed what would prove to be a successful airship, achieved partial triumph yesterday morning when his machine, attached to an auto, soared about two feet from the ground. ”

And that was the first and last flight of the Lohner No. 2.

Later that summer, at the Central Canada Exhibition, it was on display in the Machinery Hall in which it was built. An engine and propeller had since been installed — the investors having been excited by the short hop in July, had fronted him the money. While on display, the engine was often run. He charged 10 cents for adults and 5 cents to children. In a sort of primitive precursor to today’s modern full motion simulator rides, the Citizen reported that a fair goer at the Exhibition,

“could go to a quiet corner of the field and enjoy a ride in a really [sic] aeroplane — no less than that of his old friend Herr Lohner, the German inventor, whose experiments in aviation have been attracting the attention of Ottawans lately and who is now furnishing a most realistic imitation of a trip through the air in his biplane without any of the attendant dangers.”

And the following day:

“The big aerodrome of the German inventor Lohner with its flying machine is attracting many of the visitors to the fair. Lohner himself and a spieler [a circus barker - Ed] are in attendance all the time to explain the workings of the machine. Yesterday the motor was running and many took their first ride in an airship. … …The big biplane is certainly worth seeing. The propeller is going merrily all the time and you can get all the sensations of real flying by taking a seat in the aviator’s chair.”

Originally Lohner had promised that his aerodrome would make demonstration flights after the Exhibition at the Lansdowne rifle ranges, but fortunately, this did not come to pass. It was reported that after the fair, he took himself and the contraption away to Montreal, leaving unpaid bills and disappearing. There were no other stories about Lohner in the Ottawa papers after the fair ended, and the embarrassing foray into aviation seemed to be swept under the carpet. The “Little German” had conned the city’s doyens, and perhaps himself, but interest in aviation continued in Ottawa.

My colleague Richard Mallory Allnutt found a strange 1915 coroner’s report from the northern bush community of Temiskaming, Ontario that notes the discovery of a man found frozen to death in a remote forest cabin. The corpse was that of an estimated 37-year Swiss man by the name of George Lohner. It was estimated by the coroner that Lohner, who was then a prospector, had died on Christmas Eve of 1915. It appears that Lohner had died still hoping to strike it rich.

An article in The Ottawa Citizen on March 14, 1916, six years almost to the day that his Lohner No. 1 came to grief at Lansdowne Park, reported the details a couple of months later:

LOHNER, THE “AIRSHIP” MAN FOUND DEAD

Mysterious Inventor Who Once Held Ottawa’s Interest Frozen to Death in Porcupine Region

SOUTH PORCUPINE, ONT. March 12. The mystery surrounding the disappearance of Paul Lohner [sic], of late years a prospector in the Porcupine Camp, but previously an inventor, has been cleared up by the finding of his body on a lonely cabin by two fellow prospectors St. Paul and Brown of South Porcupine, who have arrived in town with it. Lohner has been missing since Christmas but fellow prospectors who knew him thought it possible that he had started out into a new district in hope of locating gold on some claims many miles back in the woods. Knowing, however, that he did not take more than two weeks’ supply of provisions with him, they became uneasy when he did not return in due time. Search parties had been sent out from time to time, but all were unsuccessful until St. Paul and Brown started out several days ago in search.

How Remains Were Found

Two weeks ago St. Paul reported seeing a body in a disused cabin and reported the matter to the police. As this was not within four miles of the road Lohner was thought to have taken, no one thought of connecting the incident of his disappearance with the reported finding. The matter was reported to the provincial police but it was not until last week that any move was made towards confirming the story. The two were sent out by Mr. G. H. Gauthier, mining recorder at Porcupine.

From the story told by the two men it appears that Lohner, whose claims were in McArthur township, had apparently left his own cabin to return to South Porcupine and had got on a wrong trail in a storm and lost his way.

Ottawa Knew Him Well

At one time, about eight years ago [sic], Paul Lohner [sic] was much talked about in Ottawa. He was the builder of the Lohner “aeroplane”, which once upon a time occupied a place on the midway on the Ottawa exhibition. Lohner was born in Switzerland and when a boy of seven years met with a mishap which left him lame for life. He came to Ottawa without a cent in his pocket but with the idea that he could build an aeroplane. He succeeded in interesting a number of Ottawa men who assisted in the way of supplying him with materials. He built the “aeroplane,” a crude contrivance of wondrous design, but numerous tests at the exhibition grounds proved that the invention could not be made to rise in the air. The tests were made by attaching the framework, minus an engine, to an automobile and speeding around the track before the grandstand. He went to Porcupine from Ottawa, after his failure, following a year of hard work, during which he struggled and suffered privations almost night and day and slept out at the grounds beside his invention to guard the secrets of its construction.

An ignominious ending for a man who had such large dreams.