DONALD LAMBIE’S WAR - Episode Two

April, 2020

Originally planned as a two part series, this story of one man’s experiences in the Second World War will now span three episodes. It is the story of an ordinary line Spitfire pilot at the very end of the war told through a series of unpublished photographs from an album discovered in an antique store in Ontario.

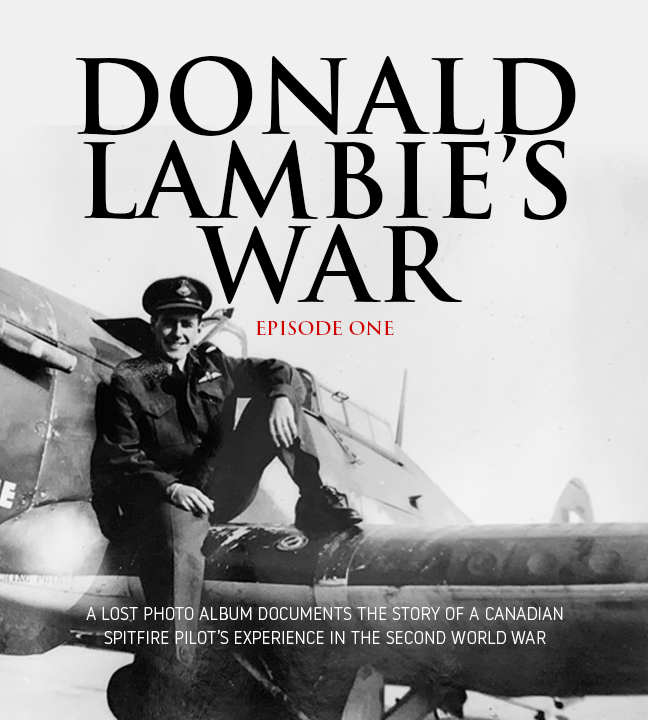

When last we saw our intrepid aviator, in Episode One of Donald Lambie’s War, he had boarded Hired Military Transport (HMT) Andes in Halifax for a crossing of the Atlantic.

At this point in the war, with Germany on the defensive, the time left to join the fight was diminishing for Lambie and his comrades. The summer before, the Wermacht had made no headway and were fought to a standstill at Kursk. The previous winter and in the summer of ‘44 they were pushed steadily across the Ukrainian Steppe, out of Crimea, back from Odessa and Sevastapol and west from Leningrad in the north. The Soviets were clearly in the ascendancy in the East. Stalin and the Russian General Staff were pushing the Allied leadership hard to launch an invasion on Germany’s western flank, to penetrate the Atlantic Wall and release pressure on the Soviet Army in the East.

In the Mediterranean, the Germans had been forced from North Africa and Sicily and were slowly being pushed up the length of Italy. The Italians were long ago done and Co-Belligerant forces were even fighting the Germans to win back their country. It was clear to anyone with a newspaper subscription and a basic understanding of extrapolation that Germany would eventually lose the war. For eager and committed men like Lambie, it was entirely possible that they would never get the chance to contribute to victory.

Pilot Officer Donald Walter Lambie during his training in Canada in 1944. By the time he landed in Europe in the summer of 1944, he was already promoted to Flying Officer. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie’s troop ship left Halifax at the beginning of June. Then, somewhere mid-Atlantic, while he was taking in the warming summer air on the officer’s upper decks of HMT Andes, Allied forces fought their bloody way ashore at Normandy and the long-prepared for Second Front was opened. No doubt an announcement was made on the ship’s loudspeakers. As on many ships in the invasion fleet, General Eisenhower’s message to the invading troops may very well have been read out loud:

“You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade,

“The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is will trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.

“But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man-to-man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to Victory!

“I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!

Lambie knew by now that he was going onward to an Operational Training Unit (OTU) somewhere to learn to fly a front line fighter — possibly a Spitfire, P-51 Mustang or Hawker Typhoon. His recent Advanced Tactical Training course at Camp Borden taught him much about working air support for ground troops and armoured units and his thoughts about his immediate military future must have included training up on the beast known as the Tiffy, the pilots of which had a shorter lifespan than others. All these things must have been swimming around in his head as he lifted his kit bag in Liverpool and walked down the gangway and on to the land of his parents, a country he no doubt loved as much as Canada.

Lambie embarked HMT Andes, a 27,000 ton, 648-foot long liner of the Royal Mail Line now in the service of the Royal Navy, on June 2, 1944. From October 1943 to June 1944 Andes spent eight months transiting back and forth across the Atlantic, usually from New York or Halifax to Liverpool or vice versa. One of her last voyages of this period in her illustrious war career was to Liverpool with Lambie and some of his friends aboard.

No. 3 (RCAF) Personnel Reception Centre

Innsworth, Gloucestershire, June 11 to August 3, 1944

When Pilot Officer Donald Lambie arrived in the UK aboard the troopship HMT Andes, his first posting was to the No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre (PRC) detachment at Innsworth, Gloucestershire about 150 miles south of Liverpool. This was a satellite facility of No. 3 PRC based at Bournemouth, Hampshire on the south coast of England. No. 3 PRC with its two satellites at Innsworth and Hastings, was the clearing house for all incoming RCAF personnel after they stepped off their ships. Here they would remain until a place was found on an OTU.

Lambie must surely have enjoyed his four weeks at Innsworth, for, by the end of the war, there were nearly 5,000 people living on the station, three quarters of them with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force!

RAF Fairford, Gloucestershire

August 3 to September 6, 1944

Lambie and others waiting for a place to go languished in the presence of 4,000 women for nearly a month at Innsworth, so perhaps it was time to move some of these men elsewhere. On August 3rd, he was posted to RAF Fairford, some 35 kilometres to the southeast of Innsworth. Lambie writes in his personal chronology that he was engaged in “supernumerary aerodrome control”. Perhaps they we employed assisting the RAF staff in the control tower or other dispatching areas. RAF Fairford was a relatively new airfield having just opened a few months earlier in January, 1944. The timing of Lambie’s posting to Fairford is interesting as it was one of the bases from which gliders were towed to participate in Operation MARKET I (part of Operation MARKET GARDEN) a week after Lambie left. Fairford-based Short Sterlings of No. 620 Squadron, RAF departed from that field with Horsa gliders in tow filled with paratroops from the First Airborne Division. It seems possible Lambie was there to help out in the logistical and organizational activity related to the massive and ill-fated operations, arrangements for which would most certainly have started while he was there.

Lambie spent nearly a month at RAF Fairford and left just a few days before that station was used by the RAF in Operation Market Garden. Here, paratroops assemble on Fairford’s infield in front of Short Stirling Mark IVs of 620 Squadron RAF parked on the perimeter track. In the distance we can see one of the giant Horsa gliders they will travel on to the Netherlands. Photo: Imperial War Museum

It was also likely that during his two months at Innsworth and Fairford, he explored the UK and spent some time with his relatives near Cambridge. The last time he was in Great Britain, he was a young boy dependent on his mother and Aunt Amy, and now he was a fully-grown, educated man and a fighter pilot — a modern day knight off to the crusades. Despite the seriousness of his purpose and the regulated life he was signed on for, Don Lambie could still find free time to explore, to renew old relationships with family and build new ones with comrades and female companions. It was a heady time for the young Canadian.

While awaiting a posting to an Operational Training Unit, Lambie spent some time at the home of his Aunt Amy and uncle. Judging by the lovely bungalow and extensive gardens, these folks were relatively well off. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie and Aunt Amy, the headmistress at his old elementary school at Bolnhurst, pose in the garden of her home. The last time Amy had seen Donald was in 1930, 14 years previous. Where once there was a mischievous boy, there now was a handsome, elegant, committed young fighter pilot. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

Aunt Amy and her husband lived near Bedford, about 25 kilometres from Cambridge. When their nephew Donald came to visit, they took him on a visit to that beautiful university town in their 1939 Ford Prefect Saloon. The war is on, gas is rationed and there are mostly military vehicles in the car park, but somehow, they managed to acquire petrol. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Standing on the lawn outside the main gate and Porters’ Lodge of King’s College, Cambridge, Lambie snaps a shot of the shops and apartments along King’s Parade with the Church of St. Mary the Great (or as it is known to locals Great St. Mary’s) in the background. In addition to being a parish church in the Diocese of Ely, it is the official church for the University of Cambridge. As such it has a minor role in the university's legislation: for example, university officers must live within 20 miles of Great St Mary's and undergraduates within three. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Quite literally nothing has changed in the intervening 80 years since Donald Lambie took the previous photograph, but Google Streetview brings it to life in living colour. I am not a fan of colourizing old black and white movies, but using modern colour imagery does show us that King’s Parade is not, nor was not, a dark grim place in the way these old photos portray it. Photo: Google Streetview

On his visit to Cambridge, Lambie stood beside the famed Front Court of King’s College, University of Cambridge. The Late Gothic spires of King’s College Chapel are at left. The cornerstone for the chapel was laid in 1446 (before Columbus’ voyage to America) by King Henry VI, so Lambie was there almost exactly 500 years afterwards. The fantastical structure in the centre is the Gatehouse and Screen containing Porters’ Lodge and the Mail Room where students have pigeon holes for their mail. Only fellows of the college, people speaking to fellows and ducks are allowed to walk on the court’s lawns. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Today, Front Court is much the same as in Lambie’s time, save for less ivy on the walls of the Gate House. The manicured lawns remain off limits to tourists and students. The fountain at left was built just 70 years before Lambie’s visit and features a statue of Cambridge founder King Henry VI holding out the charter that allowed the college to be built. Beneath him sit statues representing “Religion” and “Philosophy”. Photo: Google Maps

In Donald Lambie’s photo album from these three years of his life, they are many photos of him with attractive female companions. It appears he met Carolyn Granger, the elegant young woman in the smart suit while he was in Great Britain awaiting a posting to an Operational Training Unit. For more than a year (including after Lambie returned to Canada), Ms Granger sent him photographs of herself and hand written notes on the back that seemed to indicate she was quite sweet on the handsome young Canuck. In the photo at right, taken in April 1945 while Lambie was in combat with 417 Squadron, she worked up the courage to sit upon a tomb in the cathedral’s forecourt. She wrote a saucy little note on the back side which reads “Don’t you think the view of Winchester Cathedral is rather good? It took quite a lot of nerve to sit on top of the tomb, but as you can see… I took the plunge. Sincerely Carol.” Surely photos like these meant a lot to a pilot risking his life in Italy. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

While he was in Great Britain, Lambie visited RAF Skipton-on-Swale (where he took this photo), which was home to two Canadian heavy bomber squadrons operating Handley-Page Halifax heavy bombers — 433 and 424 Squadrons. One wonders if it was to visit a friend from his training days. It was pretty common in those days for nose art on Canadian Halifaxes and Lancasters to begin with the same letter as the aircraft code. The nose art “Carolyn” suggests that this was possibly either 433 Squadron’s “C” aircraft (BM-C) which carried RAF serial No. MZ807 or 424 Squadron’s (QB-C) which carried LW164. Both aircraft were later lost — Halifax MZ807 on December 2, 1944, and LW164 two months later in January. The entire crew of the 433 Halifax was lost when it was shot down over France and all but one of the 424 Halifax crew were killed when it crashed on take-off at Skipton-on-Swale. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

No. 3 (RCAF) Personnel Reception Centre,

Bournemouth, Hampshire, September 6-13, 1944

The ORB for No. 3 PRC at Bournemouth tells us that Lambie was only one of an astonishing intake of 400 officer pilots and 81 sergeant pilots who arrived that same September day, along with many more officers and NCO navigators, flight engineers, wireless operators, bomb aimers, air gunners and hundreds more ground trades. When he left on September 13, he was one of just 8 officer pilots who had orders in hand for operational training or other purposes.

Though Bournemouth was a seaside tourist town, it was not always a safe place during wartime. There were nearly 10,000 Canadian airmen stationed there in May of 1943, accommodated in scores of requisitioned hotels, homes and luxury flats, and their presence in the town prompted a daylight “tip and run” bombing raid by the Luftwaffe. At midday on Sunday 23 May 1943, 26 Focke-Wulf 190 fighter-bombers, flying at wave-top level across the English Channel to avoid radar detection, climbed up over the town and bombed the central area, destroying 22 buildings and damaging a further 3,000. There were heavy casualties among the aircrew stationed there and several hotels were destroyed, in particular the Hotel Metropole where nearly 200, mostly Allied airmen, lost their lives including Canadians.

By the time of Lambie’s arrival on September, 6, 1944, however, the Luftwaffe presence had been pushed back into Belgium. Billeted at one of the many tourist hotels in the city, Lambie would spend only about a week here before a posting to Morecambe, Lancashire near Blackpool. During the week he did spend here, Lambie likely had a smashing time. Local restaurants and pubs, though hampered by rationing, now had several years of experience catering to Canucks, Aussies, Kiwis and Yanks with money to spend.

The aftermath of the Luftwaffe attack on Bournemouth’s once-beautiful Hotel Metropole.

The smiles of Canadian airmen holding the wing of a downed Focke-Wulf Fw-190 after the Luftwaffe attack on Bournemouth belie the trauma of the event. Photo via BBC

No. 2 Personnel Dispatch Centre,

RAF Morecambe, Lancashire, September 13-28, 1944

Just prior to boarding a troopship for the Middle East, Lambie transferred to Number 2 Personnel Dispatch Centre at RAF Morecambe. This station was not a flying station, but rather a collective name given to multiple hotels and facilities used by the RAF in and around the Lancashire seaside town of Morecambe, a few kilometres north of Blackpool. The International Bomber Command Centre at the University of Lincoln explains:

“Morecambe had a number of different roles within the RAF — a basic training unit, including WAAFs (about 80% of whom went through Morecambe), driving school, training centre for engine fitters and airframe fitters, transit camp [No. 2 PDC- Ed] and hospital. There was a non-operational airfield with three hangars where airframe fitters learned their trade on withdrawn Whitley bombers, whilst engine fitters worked in the numerous commercial garages commandeered, including the council bus garage. After basic training, recruits would move on, unless enrolled in driving courses (WAAFs) or were trainee fitters.”

As well as housing training facilities, Morecambe was, through No. 2 PDC, a collection point and jumping off station for overseas air force postings. Here, Lambie would linger for two weeks and acquire any tropical uniform gear needed for work in Egypt and Italy. The only reason I can see for Lambie to travel the 300 miles from Bournemouth in the south of England to Morecambe near Blackpool was to join a troopship departing from that port or possibly from Liverpool, 60 kilometres to the south. I believe either port was where he boarded HMT Alcantara for the voyage to Egypt, though it is not noted anywhere in Lambie’s records.

Several of the seaside town of Morecambe’s holiday hotels were requisitioned for various ancillary RAF requirements. The modernist streamlined Midland Hotel (Left) became a military hospital while the waterfront Clarendon Hotel (Right) was used as a local RAF headquarters and later accommodations for personnel bound overseas. Photos: Wikipedia

Off to Egypt

On September 28, 1944, Lambie embarked the troopship HMT Alcantara with other fighter pilots from Canada and enjoyed a sunny voyage south to Gibraltar and then across the length of the Mediterranean Sea to Egypt. By this time in the war, the German U-boat threat in the Mediterranean Sea was over. U-960, the last submarine to make it past Gibraltar and into the Med, was hunted to exhaustion in March of 1944 and the weaker Italian submarine threat had ended in 1943 with Italy’s surrender. I imagine Lambie truly enjoying his transit of the blue Middle Sea under sun-dazzled skies and cooled by fresh breezes on an adventure to a totally foreign world.

Lambie sailed from England for Egypt aboard HMT Alcantara on September 28, arriving at Alexandria in October 11, 1944. In 1939, the Admiralty requisitioned Alcantara and had her converted into an armed merchant cruiser. The mainmast and a forward dummy funnel were removed to increase the arc of fire for their anti-aircraft guns. Alcantara was sent to Malta for further modifications, but en route she had a major collision with the Cunard ship RMS Franconia. Alcantara was refitted as a troopship in 1943, and remained on that role well after the end of the war, and did not return to civilian service until October 1948.

No. 22 Personnel Transit Centre (PTC)

Almaza, Egypt, October 11 -14, 1944

Alcantara disembarked her passengers in Alexandria on the south coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the first week of October. Lambie was taken on strength at No. 22 PTC, Almaza on the eleventh. Given that he would need to get to Almaza (which was in a suburb of Cairo) from Alexandria, it’s likely that his disembarkation was before the 11th. RAF Almaza had been an air station since the days of the Royal Flying Corps of the First World War when it was known as Heliopolis. The fledgling Egyptian Air Force found its roots there in 1932. It has the distinction of being one of very few RAF bases ever attacked and bombed by the RAF — which they did in 1956 during the Suez Crisis.

Lambie spend only a few days posted to 22 PTC before he was officially moved under the command of No. 5 Middle East Aircrew Reception Centre. I doubt he was physically moved from one to the other as they were both situated at RAF Almaza/Heliopolis.

Lambie (foreground) and a few of “the boys” including Canadians Jack Leach and Bob Latimer (the two men at right) in the background at Damanhour Station, October 11, 1944. Damanhur is a city about 50 kilometres east of Alexandria, Egypt in the Lower Nile Region. This is likely a train change on the rail line from Alexandria to Cairo (Almaza) where they would join No. 22 PTC that very same day. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

No. 5 MEARC, (Middle East) Aircrew Reception Centre

Heliopolis, Cairo, October 14 — November 11, 1945

Lambie was probably getting tired of the “hurry up and wait” system he was forced to endure. Finally arriving in Egypt, he no doubt was looking forward to strapping on a Spitfire and getting to the work he had spent so many months training to do. The very thought of having gone through two years of training and then missing out on the big show was anathema to these young and eager men. Unfortunately, once he got to Heliopolis/Almaza, he was subject to yet another month-long wait for a slot on a Spitfire course.

In October of 1944, Lambie and his friend Dave Evans (Left) met up with some young women of the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women's branch of the British Army during the Second World War. They were Captain “Paddy” Arthur and Captain Patricia Rawlinson. Lambie picked his friends well. Flying Officer David Evans, a Canadian from Windsor, Ontario would remain in the RAF after the war, and eventually become Air Chief Marshal Sir David George Evans, GCB, CBE, a very senior commander of the Royal Air Force. At the end of the war, after flying close air support operations in Hawker Typhoons with 137 Squadron he would be one of the first RAF officers to enter Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. In 1964, he was the pilot for the British 4-man bobsleigh team at the Olympics at Innsbruck, Austria where Canada took the Gold Medal. On another occasion, he represented Canada in the Commonwealth Winter Games and won two bronze medals. In 1973 Evans was made Air Officer Commanding No. 1 Group and in 1976 he was appointed Vice Chief of the Air Staff. He went on to be Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief RAF Strike Command the following year. He was Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff from 1981 to 1983. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Air Chief Marshal Sir David Evans, GCB, CBE about to fly an RAF Panavia Tornado strike bomber. Though he remained in the RAF after the war and was eventually knighted, Evans never gave up his Canadian passport and returned often to visit. He has the distinction of being made an Honorary Citizen of three cities including Winnipeg and Dunnvile, Ontario where he earned his wings. Born and educated in Canada, Evans was commissioned into the Royal Air Force as a Pilot Officer under an emergency commission during the Second World War. He underwent pilot training in Canada and he then completed operational training in Ismailia before joining a Typhoon squadron in Europe. LGen (Ret’d) Lloyd Campbell, former Commander of the Canadian Air Force and highly accomplished fighter pilot had this personal remembrance of Evans. “On August 20th, 1977, I had the pleasure of flying Sir David Evans in a CF-104D (tail number 104649). He was a very charming man and the duty of taking him for a trip in the 'zipper' was a real pleasure. I was introduced to him the evening before our flight at a dinner in his honour. When we had the chance to chat after dinner, I asked him whether he wanted the front seat or back. He acted quite surprised at the offer but, when I told him I could do everything necessary to safely operate the aircraft from the back seat, he enthusiastically volunteered to take the front. The next day was a quite pleasant summer day in Cold Lake and, as we were strolling out to the jet with our 'chutes on, he said to me, rather conspiratorially "Lloyd, something I suppose you should know is that the last fixed-wing aircraft I flew was the VC-10 ... so, if you want to change your mind, it's OK" or something along those lines. Nevertheless, we stuck with the game plan and had a great trip together ... some supersonic flight at tree-top level in the range, some simulated attacks and then a return to base for some touch-and-go landings before a final full stop ... all of which, as I recall, Sir David greatly enjoyed and (with coaching) carried out with admirable skill.”

One of the women ATS officers in the photo above was Captain Pat Rollinson. Thanks to the dogged and digital sleuthing skills of Richard Mallory Allnutt, an aviation writer and historian, a brief story of Rollinson emerged. Patricia Kathleen Rollinson, from Camberwell, London joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service in 1941. She joined as a Sergeant (as shown above) but was promoted to Subaltern in March, 1942. By the time she met Lambie, she had just been promoted to Junior Commander (Temporary), the ATS equivalent of a British Army Captain. She married a man named Philip Arthur Warner in Hendon during 1946. Warner had been at Singapore with the Royal Signals Corps and endured the war in a Japanese POW camp. They had four children together. Sadly Patricia died in Hove during January, 1971, while Warner lived until 2000. Her Royal Highness Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen of England was also an ATS officer during the war and served as a transport driver.

Lambie (right) and three friends (Al, Ted and Jack according to the caption on the back) pose near their tent city barracks at Almaza (Heliopolis), Egypt in October, 1944. If you look closely, you can see Lambie’s ubiquitous camera in his hand. Lambie and his friends were encamped here for a month before being posted to RAF Ismailia. RAF Almaza (formerly RAF Heliopolis) was first established as a civilian aerodrome in 1910 in Heliopolis, a north-eastern Cairo suburb. It would be taken over by the RAF prior to the war. For the first few days here they were with No. 22 Personnel Transit Centre and the rest of the month with No. 5 Middle East Aircrew Reception Centre (MEARC)— both at Almaza/Heliopolis—while they sorted out their posting to the Spitfire OTU at Ismailia, near the Suez Canal and the Great Bitter Lake. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Operational Training on Spitfires at 71 OTU, Course No. 70

RAF Ismailia, Egypt — November 11, 1944 to January 13, 1945

Royal Air Force Operational Training Units (OTU) were training schools that prepared aircrew for operations on a particular type or types of aircraft or roles. No. 71 Operational Training Unit was formed in June of 1941 at RAF Ismailia, on the Suez Canal north east of Cairo. Its task was to train Spitfire pilots and acclimatize them to desert conditions. The desert war was now over, but operations farther north on the Italian front were definitely going to be dusty and marked by deprivation and poor sanitation.

Ismailia had been an active station from the days of the First World War and as such had decades to improve living conditions for Royal Air Force officer pilots and other aircrew. There was even a tennis court!

For the first time, Lambie would have his own batman (or at least shared with a couple of other officers), a servant who would be responsible to wake him, make his bed, bring him refreshments, shine his shoes and maintain his kit. Unlike batmen in the UK who were generally low-ranking serving members of the RAF, his batman in Ismailia was a local man in kaftan and fez.

In December of 1944, Lambie poses with his “two camara-shy batmen”. Being an officer, Lambie benefitted from having a personal servant to clean his clothing, shine his shoes, clean his room and generally look after his well-being. Sergeant pilots who endured the same hardships and dangers as the officers had no such help. The man in the dark fez was Absid and the fellow in the white “kufi” was named Hassan. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The OTU had two-seat Harvard trainers for pilot assessment, Hurricanes for refresher flying and of course Spitfires. Of his first ten flights at Ismailia, Lambie flew a Harvard six times and a Hawker Hurricane four times. Of those six Harvard flights, five were flown for assessment with an instructor named Flight Lieutenant Houle. Lambie has made a small notation next to Houle’s name: “CO 417” and then in another column note that he was “A good type. From Alberta”.

Albert “Bert” Houle had in fact been an instructor on Spitfires at the nearby No. 73 OTU, Abu Sueir, but that was more than a year before and he was indeed the legendary commanding officer of 417 Squadron, but by the time Lambie got to Ismailia, Houle, a Squadron Leader, was back home in Canada after being wounded in combat in February. Though Albert was his first name, he was not from Alberta, but rather the north shore of Lake Superior. The “CO, 417” note on his log book must surely have been a post war notation and Lambie got the two men mixed up. If anyone out there has a bead on the No. 71 OTU instructor known as Flight Lieutenant Houle from Alberta, Canada, please contact me at domalley@aerographics.ca.

The legendary Squadron Leader Bert Houle.

The young Canadian fighter pilot’s first flight in a Spitfire took place on December 4, 1944, nearly a month after reaching the OTU — a one hour freewheeling flight after which he noted in his logbook: ”What a Kite — just like a bird!” He was finally, two years after enlistment, a Spitfire pilot! Lambie would spend three full months at Ismailia learning to fly the Supermarine Spitfire Mk VcT, a tropicalized variant of the Spitfire, the fighter of Lambie’s dreams.

In the beginning at Ismailia, the pilots were assessed in the Harvard and then brought their rusty skills up to speed on the Hurricane before stepping into the pilot’s seat of a Spitfire. In their Spitfires, they practiced close formation, battle formation, spins, deflection attacks, air combat, climbs to altitude, low flying, interceptions and more. After about 10 hours in Hurricanes and 21 hours in Spitfires, Lambie graduated to the Air Firing Squadron at No. 71 OTU where he got down to the nitty gritty of gunnery — quartering and stern attacks, circuits of pursuit, evasion and lots of shooting of their .303 Browning machine guns and 20 mm cannons.

At Ismailia, Lambie met many other airmen from Canada and around the world, some of whom would later join 417 Squadron with him. Here, in December, 1944, we see him at right making a silly face with three other Spitfire pilots on the OTU. Left to Right: Flight Lieutenant John Joseph Doyle, “Chalky” White, Royal Australian Air Force and Robert Edward “Bob” Latimer another Canadian who would become a close friend. John Doyle’s sweat shirt with “Elgin Field, Florida” emblazoned on it tells us he quite possibly learned to fly in the United States as part of the Arnold Scheme. Elgin Field was not one of the bases used in the training of RAF pilots but Clewiston on the shores of Lake Okeechobee, Florida was. Doyle likely got the shirt on a cross-country to Elgin. For the past few days I have been doggedly (with no success) trying to connect this John Joseph Doyle to another Spitfire pilot of the same name who flew as a “machal” (foreign fighter) with the nascent Israeli Air Force in the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. That pilot was apparently a Canadian Spitfire pilot in the war and became an ace after scoring one victory in the Second World war and four in the 1948 war. If anyone out there can help determine whether these two are one in the same, that would be great. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie and friends clean up before Sunday services at RAF Ismailia and pose for a photo in the garden behind the officer’s mess on December 3, 1944. Lambie’s two friends were to survive the war and rise to high levels in their careers. Dave Evans (left) of Windsor, Ontario would become Air Chief Marshal Sir David Evans of the RAF while Bob Latimer (seated) would become Assistant Deputy Minister for Trade Policy in Canada’s Department of External Affairs. On this particular day, however, they were just three chums far from their Canadian homes and seeking solace in Sunday services. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A line up of five Supermarine Spitfire Mk VcT “Trops” at RAF Ismailia in late 1944. The OTU pilots trained on war-weary Spitfires with the profile-altering, beauty-killing Vokes tropical filters. The filter was initially installed on the Mk.V for operations in North Africa and Malta to filter out the dust of rough strips which was effecting the Merlin engine’s performance and life span. Note pilot’s seat on Spitfire 49 has been removed. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A close-up of the same flight line showing Spitfire 49, a Mk VcT “Trop” of C-Flight at No. 71 Spitfire OTU. The pilot’s seat has been removed for some type of maintenance work and placed on the ground next to the fuselage. Note the bomb racks under the fuselage between the landing gear legs. Bombing would become a vital skill for Lambie as he joined the continuing campaign to push the Nazis out of Italy. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Another angle on the flight line at Ismailia — looking more like an RAF field in East Anglia than in the Egyptian desert. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A pilot at Ismailia, in Spitfire MA360, a Mk VcT “Trop”, leads Lambie in tight formation over Egypt, with the Suez Canal’s Great Bitter Lake in the distance. Spitfire MA360 spent its entire operational life in Africa, arriving in Takoradi, Ghana in the summer of 1943 and was finally struck off charge in 1946. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A course mate in Spitfire Trop No. B-46 peels away to the left near the Suez Canal as Lambie snaps another cockpit POV photo. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A group of colonial boys in front of the officers mess at Ismailia. Back row: L-R. Flying Officer Robert Latimer of Seeley’s Bay, Ontario, Flying Officer Tony Whittingham of Toronto, Ontario, Flying Officer Jack Leach, Lambie and Ron Chapman. In front is Flying Officer Jack Weekes. Weekes would make it to 417 Squadron a month before Lambie and be shot down on March 16, 1945, the day after Lambie arrived on squadron. On that day, he was with five other pilots (all mentioned in this story) assigned to dive bomb a rail line and then provide an escort to 24 Martin Maruaders of the RAF who were hitting the same line. He was last seen beginning his dive. According to the ORB, “No trace of aircraft wreckage could be found although the area was thoroughly searched. In fact, Weekes managed to survive and was captured by the Germans. It wasn’t until after the end of the war that anyone knew he was alive. He died in London, Ontario in 2017 at the age of 96. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

In this colour photo from Canadian Army pilot LCol (Ret’d) John Dicker, we see that Ismailia was much the same in the 1970s — note the particular type of metal roof pattern common to this and the previous and following photographs. Canadians returned to Ismailia thirty years after the war as part of the UN peacekeeping force known as UNEF II. This force was established in October 1973 to supervise the ceasefire between Egyptian and Israeli forces and, following the conclusion of the agreements of 18 January 1974 and 4 September 1975, to supervise the redeployment of Egyptian and Israeli forces and to man and control the buffer zones established under those agreements. Photo: John Dicker

If the number of photos is any indication, Jack Leach was one of Lambie’s best friends in his Mediterranean Sea war experience — with him at Ismailia and on squadron in Italy with 417. Here we see them both in late 1944 outside the officers’ mess at RAF Ismailia, Egypt. Leach would remain in the Royal Canadian Air Force long after the war, retiring in 1971. I am not sure what rank he attained, but by 1971, the Canadian Air Force had adopted an army rank structure, yet on his headstone he chose to be called F/L Jack Douglas Leach. He died in 2013 at the age of 91. His obituary ended with the simple statement that “Jack was a man worth knowing”. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The officers quarters in the 1970s looked a bit rough for the Canadians of UNEF II. This building, which, according to UNEF II pilot John Dicker was behind the officers mess at Ismailia, does look like the same structure pictures at right on the previous photo (minus the shutters). Photo: John Dicker

The pilots of “C” Flight, No 71 Operational Training Unit gather for a photograph at RAF Ismailia, the week before Christmas, 1944. From Lambie’s captions across a few dozen other photos we can identify a number of the young pilots. Lambie is fourth from left in back row. At left is Jack Leach who would join him at 417 Squadron. Second from the right in the back row is Bob Latimer, another of Lambie’s close friends on 417 Squadron. Fourth from the right in back is the Rhodesian Whitfield. The Canadian John Doyle, RAF is second from right in front. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Time to celebrate. Perhaps in celebration of completing their OTU course, Jack Leach lights off a “two-star rocket” over the Egyptian desert at dusk in January, 1945, while Flying Officer Shelton-Smith, an RAF Spitfire pilot from London, England looks on. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Ismailia was a well settled air base with accommodations that were a far cry from the previous Almaza tent city and what these young pilots would live in later in the war. The officer’s club included a tennis court where Jack Leach, Flight Lieutenant Ken Archer and Flying Officer Bob Latimer strike a “clubby” pose in January of 1945. Ken Archer is wearing a sweatshirt with the words USMC Air Crops, Yuma Arizona, which to me means some of his training was in the united States, possibly under the Arnold Plan. Archer, from Great Britain went on to fly Spitfires with 241 Squadron along with John Doyle and Tony Whittingham. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie was assessed by the Officer Commanding the Air Firing Squadron at Ismailia on his Air Firing and Bombing Assessment form as “Below Average” as an air-to-air and air-to-ground marksman, but scored an A- in air combat marksmanship. The OC’s remarks concluded with “Course use of rudder spoils his attacks”. Overall he was deemed an average fighter pilot which, as disappointing as that sounds, was an excellent result for any fighter pilot and proof he had mastered the Spitfire, for to be an average Spitfire pilot was to be an extraordinary kind of warrior.

Lambie and his cohort would be one of the very last groups to transition to the Spitfire at No. 71 OTU. After graduating from the course with over 38 hours on Spitfires, he was granted a one week leave. He and his course mates left on January 13, 1945 and the school ceased training on May 20, and disbanded a couple of weeks later.

On leave in ancient Egypt

January 13 to 21, 1945

When Lambie and his course mates at Ismailia had finally concluded their Spitfire training, they had some time to explore the exotic sights of Egypt. Some time was spent taking in the spectacle of the Pyramids and palaces of Cairo, but the boys wanted to get out of the grime, beggars and crush of the capital and head to cosmopolitan Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt which had a more “European” flavour. “Alex” as it was called, had been a major Royal Navy base and command centre in the “Med” since the First World War — even bigger than Gibraltar and just as strategically important for its proximity to the mouth of the Suez Canal. Here they would find many seaside pleasures as well as good hotels and less chaos.

One of the great attractions for sightseers in Cairo in 1945 and even today are the brilliant white Arabic vaults and domes of Al-Ittihadiya Palace, also known as Al-Orouba Palace or Heliopolis Palace. The beautifully kept national treasure was located a short distance from Ismailia. It is today the official workplace of the Egyptian Presidency where the president receives official visiting delegations. The palace is located in the uptown district, Heliopolis (Masr El Gedida), East Cairo. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Al-Ittihadiya Palace as it looks today. Not much has changed here either since Lambie took his photo in 1945.

Lambie and his OTU course mates knew they were near some of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and also knew they might never be back, so they spent their leave visiting the ancient sights including the Great Pyramids. I suspect that nearly 100% of the tourist trade for Pyramid touts came from soldiers, sailors and airmen during the Second World War. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Absolutely nothing has changed since Lambie’s time at the pyramid of Cheops Khufu, the Great Pyramid of Giza… except the two fallen obelisks have now been uprighted. Seeing some of these images in modern colour helps us transcend the distance created by faded and yellowed black and white photographs. That’s why we put these photos in here. Photo: Shutterstock

After completing the OTU at Ismailia, Lambie and few friends took the time to see some sights in Egypt during a two-week leave before being assigned to a combat squadron. Here his OTU mate Jack Smith catches up on the news in the Hotel LeRoi. Note the line-up of beer bottles on the shelf in the hotel room. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A period flyer for the Hotel LeRoy.

After settling into their hotel, Lambie and his pals went out to see the sights. Here he poses outside the gates of the Imperial Services Information Bureau in Alexandria, January, 1945. I found a brochure online called the Services Guide to Cairo, published during the war that describes the purpose of the Services Information Bureau there (which I assume is the same for the one in Alexandria): “This bureaux [sic] places at the services of H. M.'s Forces on leave the extensive knowledge and experience of those operating it of local conditions. Expert advice is gladly given on the best places to stay, the best places to visit, the cheapest way to do things. One of the bureaux's main activities is the arranging of entertainment by civilians of men on leave.” Clearly, the bureau functioned much the same as a tourist information office or a hotel concierge would today. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Sightseeing in “Alex” in January of 1945. Lambie (top left) and a couple of friends stop at the base of a massive statue on the Alexandria corniche dedicated to Saad Zaghloul, an Egyptian revolutionary and statesman. He was the leader of Egypt's nationalist Wafd Party. The figure shown here is not Zaghloul, but rather a supporting statue at the base of the plinth. He served as Prime Minister of Egypt from 26 January 1924 to 24 November 1924. The other pilots are John Whaley (left) and constant friend Jack Leach. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The lap of the figure at the base of the monument to Saad Zaghloul has been sat on by tourists since before Lambie’s time and glows gold with the attention.

A period photo of the Saad Zaghloul monument in Alexandria from the previous photo. At the time, “Alex” was a major Royal Navy base and military crossroads for the RAF, British Army and Royal Navy. It was also far more civilized and comfortable than Cairo — a place where airmen like Lambie and his friends could find good service, great clubs, military nurses and beachside relaxation. Photo from a postcard

Don Lambie sits on a dock railing on the waterfront of Alexandria with the Mediterranean Sea behind him. It’s taken him a long time to get here. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

On his leave in “Alex”, Lambie made an appointment with a studio photographer at Studio Broadway, 10 Rue Cherif Pacha, Alexandria (Egypt). He wanted a new up-to-date formal portrait to send his parents and perhaps the many ladies who fancied him. Fun Fact: The photographer was Yasser Alwan who, in addition to his studio work, shot images depicting daily life in Egypt for decades before the revolution of 1952. Later, his photographs would be exhibited in Cairo, New York, Frankfurt, San Francisco, London, Canterbury and Abu Dhabi. New York University Abu Dhabi hosted a retrospective of his work during the 2011-12 academic year. He taught photography at various institutions including the German University in Cairo. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Bound for Italy

When Lambie’s leave was over, he and his friends made their way back to Almaza where once again they were billeted at No. 22 Personnel Transit Centre, this time for a week. On the 28th of January, Lambie and others climbed aboard trucks at Almaza and drove across town to Cairo West Airfield where a C-47 Dakota (KK158)* of 44 Squadron, South African Air Force was fuelled and ready to board his cadre of newly-minted Spitfire pilots and fly them to Bari on the Adriatic Coast where Italy’s stiletto heel joins its boot. When their gear was stowed aboard, the Dakota’s commander Captain Du Toit, AFC pushed the throttles to full power and lifted up out of the dust and heat and flew northwest towards Alexandria. Looking out over the port wing the young aviators caught a glimpse of the endless empty Egyptian desert drifting west for as far as the eye could see.

It was a C-47 Dakota of 44 Squadron, South African Air Force that flew Lambie and his fellow OTU graduates to Italy from Cairo at the end of their leave. As part of 216 Group, Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, 44 Squadron was responsible for passenger, VIP, cargo and liaison flying on scheduled and special flights throughout the theatre to such exotic-sounding destinations as Khartoum, Teheran, Lakatamia, Aden, Cyprus, Habbaniya, Kalamaki and Algiers. Here a South African pilot of a 216 Group Dakota takes a smoke break at an Italian airfield next to the wreckage an Italian Fiat CR.42. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Soon, the sparkling Mediterranean slid into view, with the white wakes of lateen-rigged dhows, rusting coasters and naval shipping chalking the blue slate of the sea as they funnelled towards Port Said and the Suez Canal. Crossing the sand hard edge of the coast, Du Toit continued northwest towards Athens and soon they were droning across a vast blue expanse, half asleep under the drone of the engines, bundled up against the cold. After a long flight and a short stop in Athens, they lifted off again and headed east to Bari on the Adriatic. Here they were put up for the night and fed at No. 53 Personnel Transit Centre. The next day, before sunrise, Du Toit took off again with his passengers, flying south east to Malta and then, from there, north to Catania, Sicily to drop off cargo and passengers. In each of these stops, Lambie and the others got out to stretch their legs and take a close look at these now-famous airfields. Lambie’s camera was always close at hand.

The first leg of the journey from Athens to Naples brought them to Malta, the recent historical significance of which was not lost on these young fighter pilots. While the Dakota was serviced, Lambie took a few photographs of the aircraft he found there including three B-17 Flying Fortresses and a B-24 Liberator. Judging by the distant mountains, this is Luqua, one of three legendary airfields on the island. Since the date of Lambie’s flight was January 29, we know this was the day before the historic Malta Conference between Churchill and Roosevelt began. It’s possible these American heavies have something to do with that. Lambie’s photo caption says that it was a “Fort carrying one of the Big Three.” Of course this is not correct, since both Roosevelt and Churchill arrived at Malta on capital ships of their respective navies. They were at Malta for private discussions ahead of meeting Stalin at Yalta, so this would have been the Big Two, not Three. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The 44 Squadron SAAF C-47 Dakota that brought Lambie from Ismailia to Naples makes a stop at Catania, Sicily en route and the men pile out for a smoke and then a walkabout. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie photographs a group of airmen in Catania, on the east coast of Sicily. The man who is standing second from the right is wearing the cap and army-style uniform of the South African Air Force, so might be Du Toit, the Dakota’s pilot. In his caption Lambie points out his buddies in amongst the others — Whitfield (third from left), a Rhodesian pilot; John Whaley (in back, 5th from left); Red Sharman, Royal Australian Air Force (6th from left); and Bill Bower, Royal Air Force at far right. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A bare metal North American Mustang IV (P-51D) KH799 of the Royal Air Force at Catania in January, 1945. This Mustang would soon be assigned to 5 Squadron, South African Air Force in the Italian campaign and wear the code GL-B on her flanks. RAF Dakotas can be seen lining the far flight line, possibly one of them is KK158, the Dak that brought Lambie to Catania. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie’s friend Jack poses with an RAF Mustang III of 112 Squadron in at an Italian air base in Catania, Sicily. Lambie marked the back as being a photo of a P-40, so was clearly not looking past the shark mouth painted on the nose. Mustang III fighter replaced 112’s P-40 Kittyhawks after the invasion of Sicily. In the background stands the open structure of a bombed out Italian hangar. Beneath it stands a Bristol Beaufighter at right and a Spitfire at left. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Under the open structure of the Italian hangar from the previous photo, Lambie’s friend John Whaley inspects a Percival Proctor liaison aircraft, while in the background we get a bit better view of the Beaufighter. One wonders what originally covered the structure — likely canvas which could have burned away leaving the open structure. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

At Catania, Lambie enjoyed inspecting and photographing Allied aircraft he had not yet seen like this Royal Air Force B-26 Marauder. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Immediately next to the Marauder at Catania in the previous photo stood a B-25 Mitchell. We can just make out the RAF Marauder at left. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Also at Catania was this all-white RAF Vickers Warwick of Coastal Command, used for long range over-water reconnaissance, a larger development of the Vickers Wellington, the mainstay of Bomber Command in the early years of the war. It employed the same geodetic structure designed for the Wellington by the genius inventor Barnes Wallis. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie found plenty to photograph at Catania — from the most advanced Mustang fighters to antiquated biplane amphibians like this Royal Air Force Supermarine Walrus. Lambie’s caption calls it a Walrus ASR — for Air Sea Rescue — used primarily by the RAF for the rescue of downed airmen as well as reconnaissance. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

An RAF Bristol Beaufighter at Catania. Judging by the dark paint scheme and no markings, this was possibly a factory-fresh night fighter yet to be assigned to an RAF squadron in theatre. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

After the stopover at Catania, they boarded again and flew north to Pomigliano, a major Italian military airfield outside of Naples before it was captured by units of the British Army in October, 1943. Here, Captain Du Toit would bid farewell to Lambie and his new Canadian friends and continue on back to base at Cairo West Airfield. Throwing their kit in the back of another lorry, the pilots were driven a short distance south to No. 56 Personnel Transit Centre in a Neapolitan suburb known as Portici. Lambie would spend a week at Portici in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. The 1944 eruption of Vesuvius had been a major news story around the world the previous year with the Allies contending with both Nature and Nazis. No doubt Don Lambie was looking forward to seeing the legendary Vesuvius and the scars of the recent eruption. Luckily Naples and his new encampment at Portici were west of the volcano’s slopes and fared much better than the towns near Pompeii and American airfields like Poggiomarino to the east where the American 340 Bomb Group lost many of its B-25 Mitchells under the hot ash.

On the 24th of March, 1944, ten months before Lambie was there, Vesuvius exploded after a lengthy eruptive period of lava flow. At the time, the United States Army Air Forces’ 340th Bombardment Group was based at Poggiomarino Airfield near Terzigno, Italy, at the very base of the volcano. The tephra and hot ash from multiple days of the eruption buried everything and damaged the fabric control surfaces, engines, Plexiglas windscreens and gun turrets of the 340th's B-25 Mitchell medium bombers. Estimates ranged from 78 to 88 aircraft destroyed.

While at Portici, Lambie visited Naples and took this photo of a crowded harbour with Mount Vesuvius in the background. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Though higher up, this is roughly the same Naples harbour angle on Vesuvius as Lambie’s from 80 years ago. He would have been down on the waterfront on the other side of the harbour to shoot his photo. Photo: Shutterstock

Perugia or Bust

After a week at 56 Personnel Transit Centre near Naples, it was time for Lambie to start flying operationally. It had been more than a month since the last time he had flown a Spitfire or any aircraft for that matter. No operational squadron wanted a pilot whose skills were rusty, so before he could be posted to a front line unit, he was sent to a Refresher Flying Unit (RFU) in country where he could get back up to speed without the worry of the enemy at his back. Lambie received orders to proceed to No. 5 RFU which was located at Perugia, Italy, a city that sits about halfway between Rome and Florence and is the capital of the Province of Umbria. It was a long haul from Portici near Vesuvius to Perugia in north central Italy and the train trip would take them through Rome where they waited long hours for a connection on to their final destination.

After a lorry ride from 56 PTC to a train station near Portici, fighter pilots and other airmen unload baggage from their trucks and line up at a small station to board a boxcar for a trip of more than 300 kilometres north through Rome to Perugia. Note the RAF ensign streaming hard above the boxcar beckoning the excited pilots. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A photo taken in February, 1945 by a squadron mate — Lambie (upper left in braces and shirt) poses for a photo with other Canadian pilots heading toward Perugia... eventually. The caption reads: “In a siding at Rome, waiting for any engine to pull us north! Don, Smithie [Jack Smith], Chapman [in door] Phillips [squatting in doorway] and [left to right bottom] Latimer, Whitfield [the Rhodesian], Geoff Taylor, Manson, Beasley and unknown. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

No. 5 Refresher Flying Unit (RFU)

Perugia airfield, Feb 9 - Feb 16

It took Lambie’s group three days to make their way north to Perugia, travelling in freight cars all the way, languishing for hours if not days in rail yards along the way. The boys were eager to get to a squadron, as the war was obviously coming to a close and they all wanted to test their skills and their mettle. They were so close, but the war laid down another speed bump in their way — No 5 RFU was packing up and relocating to Gaudo airfield back even farther south than they had come from. Gaudo was an Allied airfield near the ancient city of Paestum, 40 kilometres south of Solerno. While they were in Perugia for a week, I suspect they had little to do, save to visit the famed Catholic town of Assisi in the hill country 30 kilometres east of the field.

The airfield at Perugia was close to the small town of Sant'Egidio and is now Aeroporto Internazionale dell'Umbria San Francesco d'Assisi. The Luftwaffe simply called it Flugplatz 296. The conditions at Perugia contrasted greatly with their last training base at Ismailia. On January 19, 1944 SAS commandos parachuted in and planted explosive charges near seven aircraft, destroying four. Two days later the airfield was made unserviceable by 200 heavy bomb craters on hangars, taxiways and runways. On April 6, 1944, it as bombed again by 36 Mitchells. By the time the British 8th Army captured the airfield in June, it was a shambles.

While Lambie was there in early February, it was raining and muddy while they prepared to pack up and convoy the entire unit — mechanics, officers, instructors, students vehicles, spares and tools— by lorry south to the coast of Italy. I’m sure, as they convoyed south, Lambie was thinking they were going in the entirely wrong direction, further from the war, further from a squadron posting. Frustration was increasing.

The Perugia airfield at Sant'Egidio in August on 1944 with RAF Spitfires of 145 Squuadron, 244 Wing parked outside the destroyed hangars. There was no desire by the RAF to repair the hangars as they would not be here long. Likely this was the same when Lambie got there six months later. Photo: forum.12oclockhigh.net

The caption with this photo reads: “The Pilots’ Mess at Perugia… Muddy What!”— proof that conditions were often rough. Perugia was well behind the lines, but even still the pilots, officers and men of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces were making-do. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

In Lambie’s photo album, there was a few post cards from the time he was in Perugia, Italy with No. 5 Refresher Flying Unit, including this one to his parents dated February 15 showing a view of Assisi. The mountain town of Assisi, birthplace of Saint Francis, one of Italy’s patron saints and Saint Clare, is about 30 kilometres from Perugia. At centre stands the mass of the Basilica of St. Francis which dates back to 1253 and houses his stone sarcophagus. On the right is the rather austere entrance to the Basilica di Santa Chiara. (Saint Clare’s). Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The very same scene today shows us that nothing has changed since Lambie’s visit to Assisi in 1945. The note penned to his parents on the back of the previous postcard hints at his growing frustration : “My Dearest Mum and Dad. I am spending a few days in this beautiful & interesting town. The people are very hospitable here and with what French I know, I am getting along well enough. This was taken from the castle on the top of the hill, where Frederick “Barbe-Rosa” I of Germany once lived. On a clear day the view of the valley with its many vineyards etc. is wonderful. The evenings are quiet and an ideal spot for a rest. Not that I need one. Hope you are both well. Your mail beginning to reach me once more. Don” Photo: Shutterstock

Standing in the Piazza Santa Chiara in Assisi, Italy, Lambie captures the rather grim-looking front facade of the 13th century Basilica di Santa Chiara. As usual, black and white photos from war time tend to make places and landscapes look tired and distressed. In fact, the Basilica is a bright pink and white limestone structure. Note the Allied ambulances parked at right. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

If you were to stand in Lambie’s spot in the Piazza Santa Chiara today, nothing would be changed, except that the basilica would now be spruced up a bit since wartime.

The caption on the back of this photo says “Our truck in the convoy. We used the tailboard for a table”. The date is given as February, 1945 meaning that this was the convoy of airmen moving No. 5 Refresher Flying Unit and its people from their base at Perugia south to a new airfield called Guado near the ancient Roman city of Paestum, south of Sorento. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

While the Paestum-bound convoy halts for lunch, the airmen are swarmed by Italian children (left) trying to scrounge anything they can from the airmen — a scene that Lambie describes as pitiful. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie’s convoy rolls through an historic Italian city with men in the trucks sitting atop the canvas roof or looking out the front, not wanting to miss a thing. I’m sure this day was burned into Lambie’s memory. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

No. 5 Refresher Flying Unit (RFU)

Guado airfield, February 20 to March 7, 1945

At the refresher flying course at Guado, there was no assessment or dual time on a Harvard. It was assumed these pilots were now fully trained and could be trusted with His Majesty’s Spitfires. Here, Lambie rolled up another 11 hours on Spitfires, this time on more modern Mk IXs. Before taking Spitfire MA707 on his first RFU flight, he signed an affidavit certifying he understood how to fly this aircraft and was “fully conversant with Flying Regulations in general and with those of 5 R.F.U. in particular; this I know the boundaries of 5 R.F.U.‘s flying area and that I must under no circumstances carry out any low flying” — obviously a unit form born of painful experience. Over a series of one-hour flights he got comfortable again, practiced something called a “pansy formation” (which I believe was close-in tight echelon formation vs the wider battle formation), bomb dives, strafing runs and tail chases.

Having completed his two last flights on March 5, 1945, he was certified squadron-ready.

At Guado airfield near Solerno, Lambie photographed this Martin Baltimore medium bomber which he claimed in the caption had suffered flak damage. Note the pilot standing on the oil drum, almost lost in the tangle. In addition to the damage on the nose, the propeller tips are bent backwards, meaning those tips struck something on both sides. If propeller tips get bent backwards when they hit the ground it means that the engines were not making power. I think Lambie was just guessing about the flak damage. The nose damage seen here and the way it is bent to the side leads me to believe that the Baltimore actually ground looped (with power pulled back), left the runway and tipped up on its nose while skidding to the left, with the very ends of the propeller blades striking the ground. By the time Lambie was here at Guado, the flak-baiting bombing war was hundreds of miles farther north. No pilot would fly his aircraft hundreds of miles bypassing other secured Allied bases if he had suffered this kind of damage. In the background sits a Bell P-39 Airacobra. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Gaudo airfield, March, 1945. Flying Officer Jack Leach takes close look at an American P-39 Airacobra at Guado airfield. A search for her name “Torrid Tessie” brings up only a P-47 Thunderbolt with that nickname. If anyone had any information on this particular aircraft and her unit at Guado, I’d love to hear from you. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Fun Fact. At the time Lambie was in Italy, tricycle-gear Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters like the one in the previous photo, were used not just by the Americans and RAF, but also by the Italian Co-belligerent Air Force (Aviazione Cobelligerante Italiana — ACI) in ground attacks on the retreating Germans. Here, the green, white and red roundels of the ACI are overpainted on the American roundel. Photo via Pinterest

Another week of waiting

Having been struck off charge with No. 5 RFU, Lambie was shifted in quick order back to No. 56 PTC at Portici, then over central Italy by aircraft to No 53 at Bari and then on to a Canadian Army rest camp at Brindisi on Italy’s stiletto heel. Once again, he seemed to be going in the wrong direction. A week later however, on March 15, 1945, he was flown nearly 700 kilometres north to Bellaria on the Adriatic coast with orders in his pocket to join 417 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. And not a moment too soon as the Americans had just secured the bridge over the Rhine at Remagen, and within days Operation Plunder would see Allies —Americans, Canadians and British—pouring into Germany. The end was nigh and it looked like Lambie would finally get into combat operations and even get to celebrate victory as a fighting man.

Coming Soon

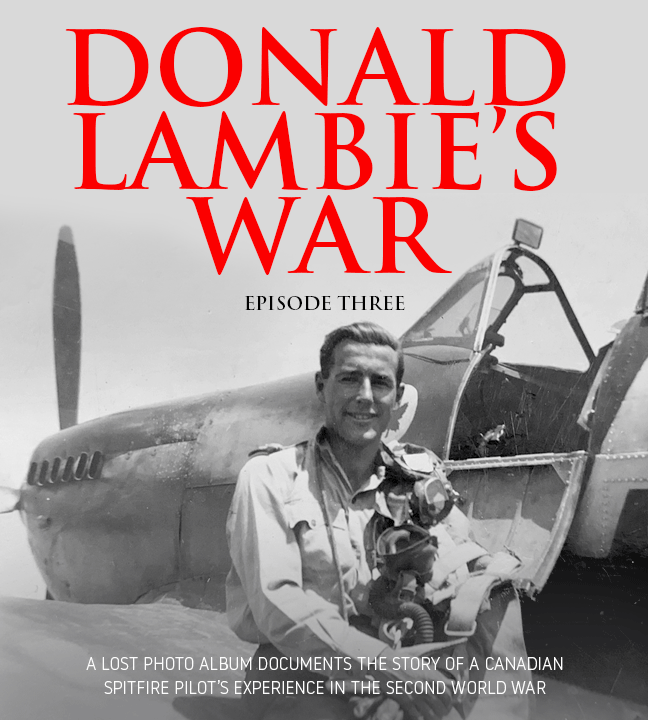

Donald Lambie’s War — Episode Three

Combat Operations with 417 Squadron, VE Day and War’s End

Stay tuned as Donald Lambie and 417 Squadron work their way from Bellaria on the Adriatic Coast to Treviso near Venice, attacking German columns all the way. There they celebrate VE Day and then give up their Spitfires and go sightseeing.