SLIPPING THE SURLY BONDS OF EARTH

Of the many photographs sent to me by the Houle family to help understand who Albert Ulric Houle really was, there is one that I keep going back to again and again. It is not a photograph of him in his uniform, or in rugged repose leaning against a Spitfire as we have all come to picture him. Instead it is a photograph that speaks to how it came to be that Albert Ulric Houle became a legendary fighting man in His Majesty's Royal Canadian Air Force. It shows a 21-year old Bert standing with his two brothers, Tim and Lint, in front of the family home in 1935. Though, at this point, he has already been in university for 3 years and living the life of a college student in sophisticated Toronto, it has not softened his body or his gaze in any way.

Broad-shouldered and barrel-chested, Bert's upper arms look as though they will split the fabric of his white summer shirt. His tree-trunk neck is thick and muscled, his jaw pugnacious, his brow dark and broad, yet this determined persona includes just a hint of a gentle, knowing and confident smile. Looking at his brothers beside him, it is apparent these are family traits. The photo speaks of hard work on the farm, muscles built the Bobby Hull way (lifting bales of hay in the hot summer sun), family bonds and the strength of the homestead. The first thing I thought of when I looked at this photo was that those brothers were there for each other, no matter what trouble one might get into, and that maybe, just maybe, they invited a little trouble from time to time. Those values of brotherhood, strength and love would be the hallmarks of Bert Houle's entire life.

Later, with his squadron brothers during the war years, Bert would give much, expect much and get much in return. He would fight with them and for them and they would follow him into Hell if they had to. It speaks volumes about the man that Bert Houle would regard the fact that he did not lose one single man from any Spitfire formation he was leading as his highest achievement in the air force. Men felt he would not let them down, and he did not.

Houle was born in 1914 in Massey, Ontario just north of Manitoulin Island. Nowadays, and I mean this with all due respect, Massey is often thought of as in the middle of nowhere. In 1914 it exemplified the rugged wilderness of Northern Ontario where men and women built their lives from the very land they walked on. Work choices for young men were limited - logging, mining and farming. It was a tough existence that rewarded young men who, like Bert, were self-reliant, unafraid of work, hard knuckled and steadfast. With blended Irish and French bloodlines, Houle grew up to consider himself Canadian and nothing else.

He may have been good with a team of horses, a hunting rifle or a field of cut hay to bring in, but Houle was destined to lead men. In 1932 at the age of 18 he enrolled in Engineering at the University of Toronto, where the tough kid from the bush matched wits and knuckles with the elite of the sophisticated city. Along with his engineering studies, Bert excelled in intramural boxing and intercollegiate wrestling, surely intimidating some opponents by virtue of his countenance alone. He was also on the varsity rifle team, which along with his hunting skills would prove great training for a shooting war. A competitive athleticism was at his very core and soon this fighting spirit would be honed in a far more deadly arena.

Bert (right) and his brothers Tim (left) and Eloie strike a proud and somewhat intimidating pose at the family’s Massey, Ontario farm in 1935.

After the Battle of Britain the previous summer, the 1941 Royal Air Force had an aura of the aristocratic elite. Into this milieu of the “Few”, came a man from the far side of the universe - hard handed, hard working and afraid of no one. Here a 17 year old Bert Houle (Left) stands with his brothers (Eloie, Linton and Lionel (Tim)) and a farm hand (second from right).

As the emerging European cataclysm loomed darkly over horizons as far away as Northern Ontario, Houle girded himself for the conflict, even going so far as to have his tonsils preemptively removed so that there would be no reason for recruiters to deny him the chance to fight for Canada. Even in remote Northern Ontario, the stories of great Canadian aces of the First World War like Bishop, Barker and Collishaw were the stuff of glory and legend for boys like young Bert. And he must have watched with curiosity and envy the bush pilots in and around his beloved Northern wilderness. If he was to hunt and fight in this war, it would be in the air.

So he joined up and his life changed to a new course that would affect all the days of his life thereafter.

As 1941 was just a few days old, Houle found himself posted out to No. 32 Service Flying Training School on the vast Saskatchewan prairie. As the RCAF was just in the process of winding itself up into the formidable fighting machine that it would become, it was a quicker route to the fight through the RAF and it was Bert's good fortune to find himself in His Majesty's Royal Air Force under the tutelage of recent combat veterans. By June he was a Pilot Officer and already in England where he was posted to No. 55 Operational Training Unit. It was here in Usworth, County Durham that he learned not only to fly fighter aircraft, but the beginnings of the knowledge he would need to survive. His Polish instructor, a Battle of Britain veteran, told him that when engaging the enemy in a dog fight, to get in close in the thick of things. From experience, the Pole knew that those on the outside of the fight or “spitters” as they are now called would be easy prey to an experienced fighter pilot. Being a boxer and wrestler, this was something Bert Houle could relate to and he never forgot the lessons he was taught.

A 55 OTU Hurricane. Bert Houle would become a formidable foe flying the Hawker Hurricane in the North African Campaign. On one day alone, 6 pilots of Bert’s squadron were shot down. Being ready the next day to face these odds is testament to men like Bert who were willing to strap in and go to work. RAF Photo

In August of that summer, Houle and his OTU mates boarded HMS Furious along with a deck full of Hurricanes bound for Egypt - the rugged Canadian farm boy found himself in the Land of the Pharaohs. With no Canadian Squadrons operating in the Desert Theatre, Bert had no option but to continue on as RAF. He was posted to 213 Squadron RAF at Nicosia, Cyprus. He was then stationed in Alexandria and waited out most of the next six months scrambling now and then to engage an enemy they were seldom able to intercept. The Hurricanes they flew were simply no longer up to the task of intercepting more advanced German interlopers.

Despite his frustrations with the Hurricane's performance, he was starting to become a master with the airplane thanks to having survived a full year with 213. Soon luck would come in the form of a formation of unescorted Ju-87 Stukas flying near the El Alamein battle line. It was late in the day, the sun had just gone down and Bert was returning to base with his wingman. Bert took his time with the group of Stukas, as a hunter would to ensure his shots counted. That night, Bert Houle nearly became an ace. Though he was only credited with two destroyed, one probable and two damaged, historians comparing German and British after action reports determined that Flying Officer Houle had in fact shot down four confirmed and one probable. His fellow pilots who had already landed, saw the massive bright flash of one Stuka exploding in the dark sky some 70 miles away. For his actions over El Alamein, Bert was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Bert Houle (no need to tell you which pilot he is) stands in the hot North African desert with fellow Canadian pilots of 213 Squadron. Though he is now part of the Royal Air Force’s history, Bert Houle was always a Canuck.

Related Stories

Click on image

Not long after the “Stuka Party”, Bert and his fellow 213 pilots participated in an operation that is the stuff that movies are made of. In mid-November 1942, 213 and 238 Squadrons landed at an abandoned airfield 140 miles behind enemy lines and proceeded to harass German convoys and positions for three days before it was discovered where they were coming from. They managed to extricate themselves from the field just moments before it was overrun by a German ground attack. But they had manage to inflict considerable damage on the enemy, strafing and destroying over 300 vehicles and virtually shutting down the road between El Agheila and Bengazi.

After a brief posting to 145 Squadron, Bert finally got his wish - to fight with a Royal Canadian Air Force Squadron - when he was, at his request, transferred to 417 “City of Windsor” Squadron. For most Canadians in the RAF, a transfer to 417 would not be their first choice. At the time 417’s reputation and record was less than stellar to say the least. Considered the laughing stock of the Desert Air Force, 417 was in dire need of a shake up. Squadron Leader Stan Turner was chosen for this task along with Houle. And the rest is history.

A four-plane formation of 417 Squadron “Trops” - Spitfire Vs modified for tropical or desert warfare with the Vokes air intakes under their chins. Designed to filter sand from the airflow, they extended the life of the Merlin engine but in fact decreased airflow and power, not to mention ruined the beautiful lines of the world’s most beautiful fighter.

After the Desert campaign, Houle took his 417 Squadron to fight the Germans in Italy. By this time they would be flying the higher performing Spitfire VIII. This 417 Spit was photographed at 417’s base in Venafro, Italy in April of 1944.

Within months, 417, flying Spitfires, went from well intended chaos to crack fighter squadron under the leadership and care of men like Bert Houle. His success was such that he was selected to be 417’s Squadron Leader in November of ‘43. By this time, 417 was fighting in Italy with Bert racking up kills and leading by example. As it turned out, 417’s most productive fighting day of the entire war was to be Albert Houle’s last combat sortie. Having shot down two enemy aircraft from a formation near Anzio, Bert found himself without a wingman to protect him and was hammered by cannon fire from a FW 190. The armour behind his seat took the brunt of the fire, but a chunk of it lodged in his neck next to his carotid artery. As a testament to his toughness, he brought the Spit home and when erks on the ground helped him out, there was very little blood, moving one ground crew to admit “The CO's got a big hole in his neck, but the man’s so tough, he doesn’t even bleed!”

Though this display of rugged determination earned him a bar to his DFC, he would have preferred to be able to remain in Italy and continue the fight. With 13 kills to his official credit, he was considered too valuable to continue fighting. Lessons learned by command about morale lows and knowledge lost from the death of Lloyd Chadburn during his third tour made them wary of sending a well-loved and highly experienced pilot back to fight. Suffice it to say that the pugnacious and patriotic Houle did not agree.

Squadron Leader Bert Houle humours an official RCAF photographer posing with his Spitfire after a dogfight in Italy.On close inspection, one notes that there is a 20mm cannon shell hole on his rearview mirror. During the action, Houle narrowly missed death as the bullet passed inches over his head from behind and through the mirror. At that point, there was no need of a mirror to tell Houle there was a German fighter behind him - so no loss. The age showing on the 30 year-old’s face speaks to the stresses of command and fighting.

Bert Houle was then repatriated to Canada. Though a Canadian in love with his country, he felt the pull of his comrades and he languished without a fight to fight. If he could not fight, he wanted out of the RCAF and he was granted a discharge. His war was over.

Bert missed flying and the RCAF (his second family) so rejoined in 1946 and went on to a second stellar career, continuing to fly. Bert retired a Group Captain and could possibly have risen higher if higher rank was awarded on skill and excellence alone. Bert’s post-war career development was somewhat hindered by lack of respect and patience for ranking officers whose careers were more important than their men.

It might seem that I have glossed over Bert’s proud and potent combat career, but this history is well known and well documented in books and on the web. Anyone wishing to learn more about Bert and the men he flew with like Stan Turner and Stocky Edwards can find ample material in the web or in their library. Albert Houle may be a legend in the annals of RAF and RCAF history, and many people know him by his exploits in the air, but that does not explain the man fully. Bert Houle’s career in the air force was created by seismic geopolitics. Without the war, Houle would have made his mark regardless. Though he will be ever associated with it, he was not defined by it. The key to his nature lay in his family roots and the family that he raised. He was a fighter long before he was a fighter pilot, a leader long before he was a Squadron Leader.

To see film footage of Houle's Massey Ontario homecoming, visit "The Story of a Hero" on Youtube. This wonderful tribute to Bert and his life was created by young Thomas Houle, a grade school boy and a distant cousin of Houle's son Craig. Houl'e inspration continues far beyond his squadron and even his own life-well-led.

It is true that Houle stepped on many toes in his career, but like his Massey family, the men under him meant more to him than the ire of some senior officer. This was not just a trait he learned in a cynical way after his combat tours, though that must have hardened him even more. It was just plain natural for Bert to stand up for himself and what he believed to be right. There are many stories that have been told about his scrapes and impolitic responses to incompetence and blustery leadership. William “Bill” McRea , former RCAF fighter pilot who went through training at the same time as Bert Houle, tells us a story from the days when they were pulling guard duty together at Portage La Prairie at the outset of their training.

“We met for the first time when we were on `guard duty' during the early construction days of the airfield at Portage la Prairie. We then went our separate ways and it was not until early 1980 that I met him again at a reunion in Toronto. I recognized him of course, because he was even shorter than I am, but he was almost as wide as he was tall, but I was amazed to hear him call `Bill McRae from Port Arthur!

“ An incident I can never forget was one day at Portage three of us were walking down the main street board walk when three huge members of the dreaded South Saskatchewan Regiment came walking towards us. The other guy and I were about to step off the walkway when Bert muttered `As you were'. We march right up to the troops, who, at the sight of that short gorilla, stepped off onto the road as we walked past!”

Though some senior “paper-pushing” officers may have loathed Bert Houle, they definitely benefited from the dashing and heroic cachet of the blue-uniformed air force officer - an image that was not earned in administration or rank-climbing but in the selfless and aggressive actions of men like Houle and Edwards. They and the men who kept their airplanes flying were and are the air force.

Bert Houle died at the age of 94 this past month. For the past several years he fought a battle with Alzheimer’s Disease. It was the one battle he could not win or control the outcome of. His son Craig and nephew Paul (an airline pilot) took to him to Vintage Wings of Canada to see our Spitfire. With the cajoling of his family, Bert got back into the Spitfire for the last time. The onset of his Alzheimer’s had played havoc with his memory but his boys were nearly brought to tears when he settled into the seat, and 60 years ago came flooding back to Bert. He grabbed the control column, checked the elevators and ailerons with a waggle.

Both Paul and Craig noticed the same thing - Bert’s thumb went instinctively to the gun tit (firing button).

91-year-old Bert Houle at the controls of the Vintage Wings Spitfire - still with the pugnacious set of the jaw. One gets the feeling that he is still humouring the photographer.

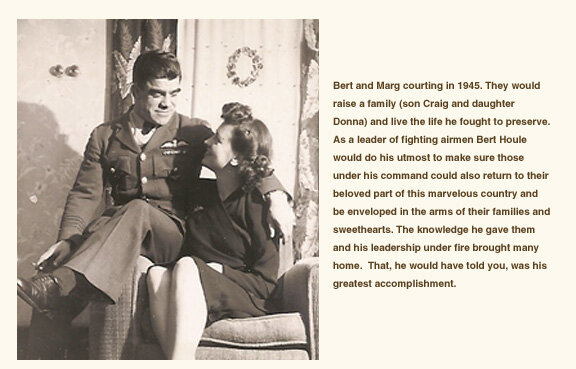

Bert was laid to rest on June 27, 2008 at our National Military Cemetery beside his beloved wife Marg who passed away last year. Marg and Bert were one as were many Air Force couples. Vintage Wings of Canada launched a Spitfire from Gatineau for the two minute flight to overfly the ceremony in heart felt tribute to this remarkable man and his wife. Unfortunately, bad weather overhead the grave site prevented this flying salute to one of Canada's great aviators. Bert's son Craig Houle and his sister Donna remarked that they could hear the far off sound of our Merlin through the murk - regardless, a poetic tribute felt by those he loved the most.