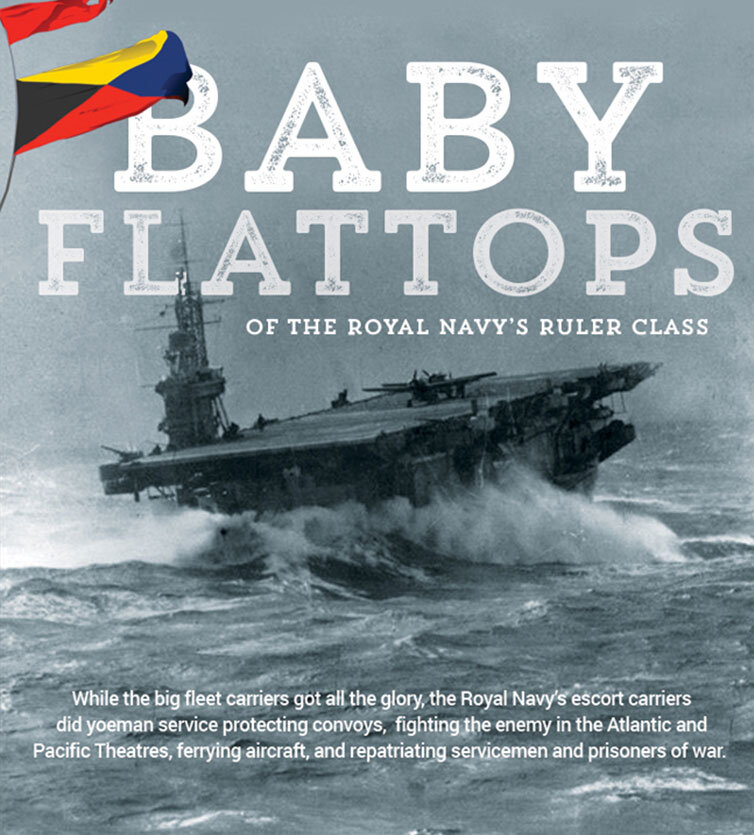

Baby Flattops of the Royal Navy’s Ruler Class

When I think of naval aviation in the Second World War, the cinema of the mind projects grainy black and white images of gargantuan fleet carriers, streaked with rust, heaving mightily in heavy seas, white foaming water streaming from gun tubs, signal flags snapping at the halyards, the silent wink of the Aldis lamp speaking like the eye of Sauron from lofty black heights. I see the burning list of USS Franklin as she faces the death she would eventually cheat. I see a kamikaze roaring like a wounded bull through the flak to drive deep into USS Essex. I see a heavy black plume of smoke rising from HMS Formidable and in front of it a white geyser of steam as she vents her system to prevent her boilers exploding.

As a young boy growing up in the shadow of the Second World War, my life was permeated with the stories and painted with the images of that massive global conflict. Our childhood games were centred on its looming presence and our drawings, readings and dreams were filled with its dark and dramatic persona. It was inescapable, but we did not wish to escape it for it was not only a world of obscenity and evil, it was a world of heroes, of pilots and gunners and captains and tank drivers—men and women who now lived in our neighbourhoods, called us home to lunch, and drove us to cub scouts.

For me, it was the imagery of warships and airplanes that seared its powerful technological brand onto my boyish imagination. When these two realms—sea and sky—came together on the windswept expanse of an aircraft carrier’s flight deck, I was gob-smacked by the spectacle of it all—the steel, the smoke, the sailors bending into the wind, the saw blade shimmer of propeller arcs, the endless bright sparkling expanse of the Pacific, the unmitigated danger of it all.

The big fleet carriers and their titanic battles in the South Pacific are surrounded by legend and drama. Images of USS Franklin’s struggle to live have set the tone for our emotional understanding of carrier warfare. Here, hundreds of sailors wait on the high side of Franklin’s list to be taken off by the cruiser USS Santa Fe. Though “Big Ben”, as she was known, survived the attack by Japanese bombers off the coast of Japan and made it back to New York, she lost more than 800 of her 2,600-man crew. Photo via Wikipedia

My picture of naval aviation is shaped by the images I found in books, by the lurid and overly dramatic box art of Revell model kits, by documentaries like Victory at Sea and Fighting Lady. The Hollywood pitch for the William Bendix B-movie classic, Battle Stations, read: “33,000 Tons of Explosive Human Emotion!” Indeed it was for a boy of 12.

Yes, these mighty flattops and their fighting squadrons took the headlines, but they deserved it. They were the prime targets of the enemy and the chess pieces in play in a gigantic and deadly board game played out across the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and the Mediterranean Sea. But to say they were the entirety of naval aviation in the Second World War is to say you know little of the subject.

During the Second World War, there were literally hundreds of vessels on all sides that could be classified as aircraft carriers; from merchant vessels with a single catapult-launched Hurricane to seaplane carriers to merchant aircraft carriers (similar to an escort carrier but without a hangar deck) to the biggest aforementioned fleet carriers. Of these, the largest number were escort carriers, the ships we have come to know as “baby flattops”. There were an astonishing 123 escort carriers built for the United States Navy, many of which were transferred to the Royal Navy after launch. These so-called “baby” aircraft carriers were hardly small—around 500 feet in length, carrying dozens of aircraft, displacing 8,000 tons and capable of speeds up to 20 knots.

While the big fleet carriers took the fight directly to the enemy and received the attention of the folks back home, the escort carriers did a myriad of necessary tasks that underpinned the very concept of carrier aviation—ferrying aircraft, replenishing aircraft, fuel and stores and carrying troops, as well as taking the fight to the enemy with anti-submarine sweeps, convoy escort, “spare deck” duty, and attacks on enemy shipping and land installations. They were the true all-purpose aviation vessels of the Second World War. The big boys made history in such battles as Leyte Gulf, Midway, Coral Sea, Santa Cruz, Taranto and Pearl Harbor, but the baby flattops supported, supplied, and suffered along with them from Operation TUNGSTEN to Operation ICEBERG. In fact, the first warship to be sunk by a kamikaze attack was the Casablanca-class escort carrier USS St. Lo in the battle of Leyte Gulf.

This lineup of Third Fleet Essex-class carriers at Ulithi Atoll during the Second World War, sometimes called Murderer’s Row (named after the name given the six big hitters of the 1920s New York Yankees—Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri), demonstrates the ascendency of American naval aviation near the end of the Second World War. From front to back, we have USS Wasp (CV-18), USS Yorktown (CV-10), USS Hornet (CV-12), USS Hancock (CV-19) and USS Ticonderoga (CV-14). To the far left is the escort carrier USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), above that USS Lexington (CV-16) and the older USS Langley (CVL-27).

Most of the escort carriers (CVEs) that served with the United States Navy and the Royal Navy were built by shipbuilding companies on the Northwest Coast of the United States, like the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation, Kaiser Shipyards, and Western Pipe and Steel. Seattle–Tacoma, with its eight massive launching ways and Kaiser of Vancouver, Washington with 12, were two of the largest. Both of these companies were building standardized mercantile hulls, most of which were built as cargo vessels, but scores were requisitioned by the US Navy at the time of their keel laying or slightly later during construction and set on a different course to be finished as escort carriers in one of three different classes: Bogue, Casablanca and Commencement Bay. There were other minor classes, but these three types made up the vast majority of CVEs.

Though all of these carriers were launched with American names, many did not serve with the United States Navy. Instead, 44 escort carriers were transferred to the Royal Navy after launch and completion under the Lend-Lease program and renamed. Most of these were built at the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding.

Most of these carriers, but not all, followed a well-traveled path to service with the Royal Navy. After sliding down Seattle–Tacoma’s or Western Pipe and Steel’s launching ways, they were completed dockside, sometimes at another facility. Following completion they underwent sea trials, then were transferred to and commissioned in the Royal Navy with a Royal Navy Captain taking command with a new crew. Then they would all sail north to Vancouver, British Columbia for modifications to suit Royal Navy standards—a long list of nearly 150 different mods to the hangar and flight decks, fuel handling systems, communications equipment and much more. This was done at the Burrard Dry Dock Co. in North Vancouver. Once this was completed, many had further work done in Esquimalt followed by a shakedown cruise, a short ammunitioning trip to Bremerton, Washington, then a maiden voyage that usually took them to San Francisco, San Diego, through the Panama Canal, and then up to Norfolk, Virginia where they would most often pick up Lend-Lease airframes (Corsairs, Hellcats, Avengers and other types built in the USA) and fill their hangar and flight decks for the ferry trip across the Atlantic. Sometimes it was both the aircraft and personnel of new Fleet Air Arm squadrons that had trained and formed in America. The crossing was invariably made in convoy from New York to Liverpool and on to Scotland. Once in the Clyde, their Royal Navy careers would begin.

Related Stories

Click on image

Some were relegated to the drudgery of aircraft ferrying and one or two never even launched a single aircraft, but most saw some combat activity either in the high arctic waters off Norway, in the swelter of the Indian Ocean or with the Royal Navy’s Pacific Fleet.

Unlike fleet carriers, escort carriers of both the United States and Great Britain had lives after their fighting careers were over. Nearly all of them sold to commercial shipbuilders after the war and were stripped down to their base mercantile hulls, then rebuilt as cargo vessels, many of which, at nearly 500 feet long, were the largest of their day. A few of them even became luxury ocean liners. These often-beautiful merchant vessels continued on for another 20–25 years or more, with most going to the breakers in the 1970s.

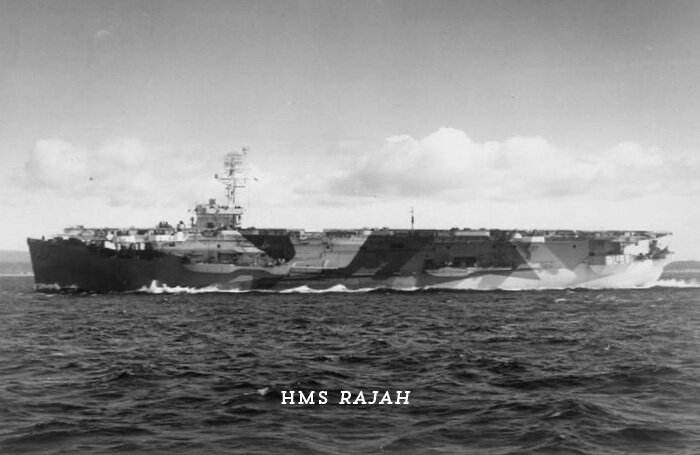

A year ago, I decided that I would do a story on these escort carriers and their role in the expedition of the war. I chose to write a story on one particular class—the Ruler Class of the Royal Navy, named not for the first ship of the same design, but rather for the naming convention from which most of these ships took their titles. Ruler-class carriers all carried short names of royal title or perhaps political leadership—Ameer, Arbiter, Atheling, Begum, Emperor, Empress, Khedive, Nabob, Premier, Queen, Rajah, Ranee, Ruler, Shah and Thane. I thought this was the entirety of the class, but I was wrong. Included in this group are also Patroller, Puncher, Ravager, Reaper, Searcher, Slinger, Smiter, Speaker, Trouncer and Trumpeter—25 carriers in all.

Once I started into this, I sort of regretted it, for it soon turned into a massive project—about five times the size of an average story put out on this site. But I kept working on it over many months and despite its 33,000 word length, I think it offers, through photographs and words, a broad glimpse into the role of the escort carrier in the Second World War as well as the lives of the sailors and aircrews that laboured on their steel decks. I offer it here; this homage to the oft-forgotten escort carrier, for your edification and enjoyment, so very grateful that it is over. If you just view half the images, you will have learned much.

In writing their stories and collecting their images, I used many websites on the internet, but particularly four outstanding websites, run by passionate naval historians whose collected works now represent a window on that world to anyone who might want to look through it. Every time I come across sites like these, I am humbled by the scope of their knowledge and the depth of their commitment to building this knowledge base and sharing it with the world.

The first is the RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk—a broad and deep website dedicated to telling the stories of the Royal Navy and its ships. Their website claims that “The Royal Navy Research Archive aims to provide a virtual museum, giving access to a range of web materials related to RN ships, establishments, units, and personnel, primarily from the start of World War One through into the 21st century. Content includes articles, short histories and the reminiscences of the men and women who served in the Royal Navy, WRNS, and Royal Marines.” This belies the depth of the passion found in its many pages, and the access to story and image offered the visitor.

The second site is the brief-yet-informative logs of individual ship movements and assignments found in the pages of Naval-History.net. This wonderful site is an excellent resource to corroborate movements and tasks of each of the Ruler-class carriers. The site makes it very easy to understand the chronology of events from a ship’s launch to its breaking. As well, the photo galleries of Nav-Source.org, which outlines the history of all American ships, were a superb place to find descriptive images. Since all of the Royal Navy’s escort carriers were at one time American ships (albeit very briefly), their stories and images are included in the site’s pages. Lastly, one of my go-to sites is that of the Imperial War Museum in Great Britain. Though their photos have only brief descriptions accompanying the photos, the sheer volume of photographs on their site guarantees that you will find something interesting for every ship.

Here now are the brief histories of each of the Ruler-class escort carriers. Please enjoy what you will of these images and texts. I’m going to bed.—Dave O’Malley

HMS Arbiter (Pennant Number D31)

When HMS Arbiter was first launched, she did not come down the ways as Arbiter or even as a Ruler-class carrier in the service of the Royal Navy, but rather as USS St. Simon (CVE-51), an American Prince William-class escort carrier. While nearly all the ships of the Ruler Class were named after cultural heads-of-state (a Scottish Thane, an Arabic Ameer, and an Egyptian Khedive), her name was more a synonym than a title, referring to someone with the power to make a decision or judgment. I suppose that if she was launched in the time of President George W. Bush, she might have been named HMS Decider! She was launched at the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation on 9 September 1943 and went straight away to the Portland Iron Works for completion. While there she was transferred to the Royal Navy on the last day of 1943, under the command of R.C. Harry. Following this work, Arbiter sailed for Vancouver for modifications to Royal Navy standard. While awaiting her turn in the Burrard Dry Dock Co., Ltd. yard, she was in the company of sister ships Queen, Speaker, Ruler, Nabob and Premier, all at various stages of completion.

HMS Arbiter moored at Greenock at the Tail o’ the Bank anchorage in the Upper Firth of Clyde, Scotland. The Tail o’ the Bank was an anchorage for the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet in the Second World War as well as a major assembly point for westbound Atlantic convoys. She appears to have been given a fresh coat of paint with an uncomplicated dazzle scheme—possibly after refit for Pacific duties. Note the seaman on a bosun’s chair scraping rust from the anchor chain. Photo: Imperial War Museum

As with all the ships of her class, Arbiter’s modifications included a lengthening of her flight deck, hangar accommodations, stores as well as safer fuel stowage and at-sea refuelling systems. Also added were modifications to internal communications systems and improvements to the “darken ship” system.

After completion of Royal Navy modifications, Arbiter embarked the 12 Grumman Avengers of 853 Naval Air Squadron from RCAF Station Sea Island, trained up her air department crews over the next week, and then set sail on her maiden voyage to Panama via San Diego. She had engine trouble near Balboa (the Pacific entry point for the Panama Canal), had to be towed to port and could not enter the canal for another 8 days. Finally, emerging at Colón, she sailed for New York via Norfolk, Virginia, training all the way. In New York, she stowed the 853 Squadron Avengers and loaded a deck full of Corsairs for Great Britain. She made it to Glasgow on 20 June 1944 where she offloaded her Corsairs and bid goodbye to the pilots and crew members of 853 Squadron and their Avengers. In June and July of 1943, Arbiter sailed back to New York and Norfolk, loaded Hellcats, Corsairs, Martlets and a Cadillac and brought them back to Liverpool. She made one more Liverpool–Norfolk–Liverpool ferry trip that year before being sent to the Harland and Wolff Shipyard in Belfast, Northern Ireland (the same shipyard where Titanic was born) for refit to make her ready for work in the tropical climes of the South Pacific.

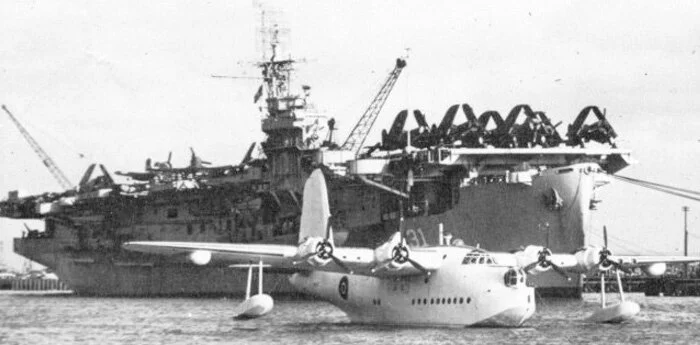

HMS Arbiter dockside with a deck full of Corsairs. The large cranes lead this author to believe this was possibly the offloading of her cargo of Corsairs at Glasgow. In the foreground floats a white painted Short Sunderland of Coastal Command, also suggesting Glasgow. Anyone knowing for sure is encouraged to write me. Photo: Imperial War Museum

HMS Arbiter gets underway on the choppy windswept waters of Greenock without her complement of aircraft. Note that the simple camouflage paint scheme offers the profile of a much smaller ship. This was intended to give a U-boat captain, under certain sun and cloud conditions, the idea that the target was not a carrier. There is no proof this camouflage device ever worked. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A nice photograph of HMS Arbiter underway at speed with her decks cleared, followed by an escort ship—standard practice for defence and for rescuing downed pilots. Photo: NavSource.org

HMS Arbiter tied up at Greenock in a photograph likely taken at the same time as the first image in this section on Arbiter. The date was 29 July 1944. The dazzle paint camouflage on her starboard side was more fluid that that on her port side. With many of the Ruler-class escort carriers painted in similar fashion, the ship’s number (31) is the best way to identify her. Photo: Imperial War Museum

After January sea trials near Belfast, Arbiter embarked the Corsairs of 1843 Naval Air Squadron and began immediate flight training in preparation for work in the Far East and South Pacific. This did not have an auspicious start, with three major accidents in four days, one fatal. During the entire training period, there were 17 incidents aboard Arbiter, the bulk of which were crashes into the barrier.

A Corsair (KD578) of No. 1843 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm rests pointed the wrong way after crashing on board HMS Arbiter on 13 March 1945, en route to Port Said from Gibraltar. The pilot, Sub-Lieutenant W. Noble, struck the round-down on landing, ripping off the tail wheel oleo and then crashing through two barriers, finally coming to rest pointing in the direction from which he came. Photo: Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm

Following this period of workup, Arbiter left her berth at Greenock on the Clyde and made course for Gibraltar and then on to Port Said at the mouth of the Suez Canal. Transiting the canal, she sailed to Bombay via the Aden Protectorate (today’s Yemen) and eventually to Trincomalee, Ceylon and then finally to the Woolloomooloo docks of Sydney, Australia on 2 May 1945, where she readied for service with the British Pacific Fleet.

For the next few months, Arbiter would serve as a ferry and replenishment (aircraft, stores and fuel) ship as well as keeping and maintaining a selection of combat aircraft used by fleet carriers in theatre (Corsairs, Hellcats, Seafires, etc.) 1843 Squadron, which had departed Arbiter when she arrived at Sydney, now rejoined her for Pacific duties. Their Corsairs were moved down to the hangar deck, with a single Corsair ranged and ready for action on the deck should it be needed. This Corsair would not have been able to return to Arbiter as her decks were covered in crated stores and vehicles bound for Manus, Papua New Guinea.

Beginning in July of 1945, Arbiter began her replenishment duties. Her first cargo of spare aircraft included a typical mix—9 Supermarine Seafires, 7 Grumman Avengers, 6 Chance Vought Corsairs, and a single Grumman Hellcat and Fairey Firefly. She would join a task force of sister carriers HMS Chaser, HMS Speaker and HMS Striker as well as defensive escorts HMS Nizam and HMS Napier.

In the last months of the war, HMS Arbiter served with the British Pacific Fleet as a replenishment carrier, standing by with a selection of Fleet Air Arm aircraft ready to supply fleet carriers to freshen stocks after damage or loss. In the foreground, mechanics fasten a cowling to a Grumman Hellcat with South East Asia Command Type C roundels, while behind can be seen a Corsair. Sailors can be seen hauling on a line to bring aboard cables to facilitate a replenishment at sea. The destroyer doing the replenishment can be seen just over the port side rear quarter. Photo: RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

During this first replenishment voyage she issued her aircraft as required and took on board five flyable Corsairs in need of repair. This was not without incident however, as she lost one new Corsair on takeoff and two of the Seafires were rendered unserviceable after a collision on deck. Another Seafire coming aboard was heavily damaged when it struck the island superstructure. After supplying stores to several escort ships, she withdrew to Manus to replenish her stock of aircraft.

On her second replenishment voyage in August, she dispersed 10 Seafires, 6 Corsairs, one Avenger and one Firefly while landing on an Avenger and 2 Seafires in need of maintenance that could not be carried out on fleet carriers. On this mission, Arbiter also carried out at-sea oiling duties. When her supplies were dispensed, she withdrew from the area and made course for Sydney, Australia.

En route to Sydney, Arbiter spent a month off the coast of Brisbane carrying out flying training for No. 2 Seafire Conversion Course—with 899 Squadron pilots practicing landing on Arbiter and operating from her deck. This training began on 15 August, the same day that the war against the Japanese ended. After this period she continued on south to Sydney. She remained in Sydney Harbour for a few days and after resupply left for Hong Kong to bring much needed humanitarian stores and medical supplies. After a short stay there, Arbiter boarded both military and civilian Australian prisoners of war, slipped her moorings and brought them safely home to Sydney.

Arbiter returned to Hong Kong with more relief supplies on 3 December 1945. She left Hong Kong with former POWs, military personnel and civilians, and began her long journey back to Great Britain via the Suez Canal. She finally dropped anchor at the Tail o’ the Bank moorage on 10 January 1946 and offloaded her passengers. Her war career ended thus.

By the end of February 1946, Arbiter was back in Norfolk where she was decommissioned and handed back to the US Navy. By April, she was struck off charge and sold to a civilian shipyard where she had her flight deck stripped off and her guts redesigned as a cargo ship called Coracero for an Argentinean shipping company. She would pass through two more shipping companies before she was scrapped in 1973 in Taiwan.

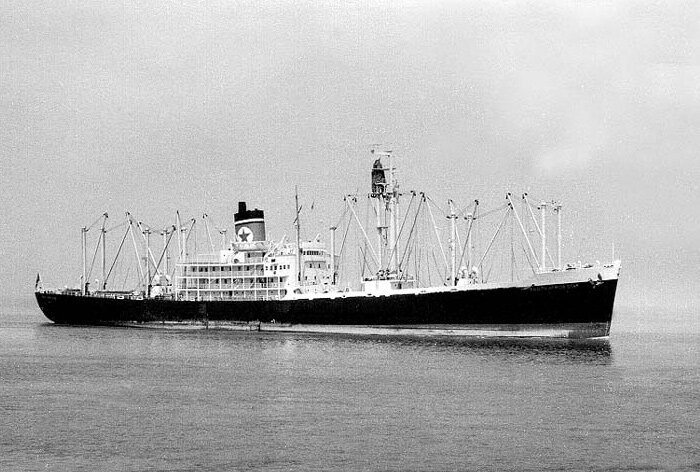

Many of the first escort carriers were built on the hulls intended for cargo or actually from old cargo ships. The Ruler-class ships were all purpose-built as aircraft carriers, but following their military careers, many were converted to civilian transport use. After the end of the Second World War, HMS Arbiter was stuck off charge and sold to Argentinean shipping line Lineas Dodero. Following a rebuild at Newport News she became a passenger/cargo ship known as Coracero. Coracero was the second to bear that name, the first having been sunk by U-384 during the Second World War. Photo: histarmar.com.ar

In 1965, following seven years with Lineas Dodero, she was sold to Philippine President Shipping Lines (PPSL) and was renamed President Macapagal and was the largest ship to fly the Philippine flag at the time. Her namesake, President Macapagal, was the Philippine president prior to Ferdinand Marcos. Under his name, she laboured on for another seven years. Here we see her tied up in Vancouver in November 1966. After serving with PPSL, she was sold and renamed Lucky Two for her last journey to the scrapyard in Taiwan. Photo: Walter E. Frost via seaarchives.vancouver.ca

HMS Ameer (Pennant Number D01)

HMS Ameer, with a deck loaded with Lend-Lease Hellcats and Avengers, is seen anchored at Greenock, Scotland on 10 January 1944 after her first Atlantic crossing. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The name Ameer is but one of many spellings of the word we now spell Emir, as in the United Arab Emirates. This is the traditional name of the tribal or royal head of state in one of several Arab city-states, such as Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al Quwain, Abu Dhabi, Al Fujairah and Ras al-Khaimah or the traditional leader of Afghanistan.

There were two aircraft carriers named HMS Ameer that were built on the West Coast of Washington in the Second World War. The first was built on the template of a Casablanca-class escort carrier in Vancouver, Washington and launched in April 1942. Originally intended for Lend-Lease service with the Royal Navy, the US Navy decided to keep her to meet their own requirements and renamed her USS Liscome Bay. As Liscome Bay, she was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine near the Gilbert Islands the following November with the loss of 644 men.

The second HMS Ameer fared much better. She was built in Seattle on the Bogue-class standard and was launched in October 1942 and, after completion in the yard, was commissioned the following June for US Navy service as USS Baffins. Baffins’ only voyage was to Vancouver, British Columbia, where she was handed over to the Royal Navy and commissioned immediately as HMS Ameer.

As with most future West Coast-built escort carriers, Ameer was heavily modified in Vancouver to meet Royal Navy requirements. There was a list of 150 mods that needed to be carried out including the lengthening of the flight deck, safety measures for oil and fuel storage.

Following her modification, Ameer worked up her new crew, made a quick voyage to Bremerton, Washington to ammunition the ship and then spent a trials period on the Strait of Georgia, practicing steaming, gunnery, radar, ASDIC and other systems.

In November of 1943, Ameer left for the Panama Canal, stopping in San Diego for stores and more equipment. After transiting the canal, Ameer dropped anchor at the Port of Cristóbal in the city of Colón, awaiting her sister carrier HMS Atheling, before journeying together to Norfolk, Virginia. Here, both carriers embarked a large number of Lend-Lease aircraft and then sailed for New York to await an eastbound fast convoy. Both carriers sailed on 29 December 1943, Ameer arriving without incident at Greenock.

A fine view of the stern quarter of HMS Ameer (at the same anchorage as the previous photo) with her twin gun tubs, the starboard one with a 5 inch gun and the other a 40 mm anti-aircraft piece. Her deck edge is lined with Fleet Air Arm (FAA) Grumman Hellcats. Initially, the FAA had proposed that the Hellcat be called the Gannet after its penchant for renaming ship-borne aircraft from the USA. The Grumman Wildcat became the Martlet (a heraldic symbol of a bird, not actually a bird) and that stuck, but the name Gannet did not. The FAA took to calling them Hellcats for simplicity, but really… it was a far cooler name. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Ameer remained at Greenock until May of 1944, undergoing conversion to become an “assault carrier” capable of supporting amphibious landings with air support. Following the installment of these improvements (better communications gear, radars and command and control spaces and equipment), Ameer embarked a number of aircraft to be ferried to Ceylon and set sail, having been assigned to join the Eastern Fleet and the 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron.

Ameer made Trincomalee on 27 June 1944 where she offloaded her cargo of aircraft. Following this, she took up ferrying duties in support of Eastern Fleet operations in the Indian Ocean. Thereupon, she was joined by the Avengers and Wildcats of 845 (Composite) Squadron, Fleet Air Arm and took up convoy escort duties in the Indian Ocean until October when she was released from “trade protection” duties and said goodbye to 845 Squadron.

Ameer spent a month or so in repair and rectification in Ceylon, then sailed for Cape Town to embark the Grumman Hellcats and crews of 804 Squadron. Whilst traveling back to Trincomalee, she conducted deck landing training and in the process lost five of 804 Squadron’s Hellcats to barrier crashes. These were offloaded for repair and she then took passage to Colombo where she disembarked the remnants of 804 Squadron.

A Grumman Avenger is “squirted off” the flight deck of Ameer while she lays at anchor in Trincomalee harbour in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the home to the East Indies Station and the Eastern Fleet of the Royal Navy during the Second World War. Flying off while in a crowded harbour was not a normal practice, with squadrons usually transferring to a land station from deep water before any long stay. Photo: Imperial War Museum

She spent a week with her old 845 Squadron, then back to Trincomalee where she met up with 804 Squadron once more (see photo below), taking part in a number of amphibious operations in the month of January: Operation LIGHTNING in Burma, Operation MATADOR and Operation SANKEY (both operations supporting the Battle of Ramree Island, Burma).

A fantastic shot of a gaggle of HMS Ameer-bound 804 Squadron Hellcats making a practice attack/close quarter fly-by off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa on 6 December 1944 before landing on her deck for the first time. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Caught at the moment of impact, a Royal Navy Grumman Hellcat (JW723) of 804 Squadron pitches hard up onto its nose after tangling with the barrier aboard HMS Ameer on 12 December 1944. The lucky pilot, Lieutenant W.M. Barr, can be seen holding onto the canopy rail to avoid head injuries. This aircraft will likely be a writeoff—the crumpled fuselage skin suggests severe structural damage. The South East Asia Command (SEAC) roundels without the normal red centres found in northern theatres of war can clearly be seen. The red centres were removed so that there would be no confusion with the red Hinomaru roundel of the Japanese Army and Navy. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In February and March, as part of Operation STACEY a photo recce operation over Sumatra, Ameer’s 804 Squadron Hellcats provided fighter cover for reconnaissance Hellcats from 888 Squadron. Whilst thus employed, 804 shot down the first Japanese aircraft by fighters from Royal Navy escort carriers (a Dinah and an Oscar).

Four Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Grumman Hellcat fighter pilots of 804 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm beam with victory immediately after landing aboard Ameer in 1945 and having just shot down a Japanese twin-engine Mitsubishi Ki-46 “Dinah”. Left to right: Sub-Lieutenant (A) Peter William Talbot, RNVR, of North Harrow, Middlesex; Sub-Lieutenant (A) Clive Donald Mortimer Barnett, RNVR, of Hereford; Lieutenant (A) Oscar Frank Wheatley, RNVR, the sub-flight leader, of Kenilworth; Sub-Lieutenant (A) James Scott, RNVR, of Stroud. Wheatley was killed in action in June, at which time he was Commanding Officer of 808 Squadron aboard HMS Khedive. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A very busy scene aboard HMS Ameer in January of 1945 as the Hellcats of No. 804 Squadron begin an operation in support of the amphibious landings by British and Indian forces against the Japanese on the Burmese islands of Ramree and Cheduba—known as the Third Battle of Arakan. The Hellcats of 804 have no centreline fuel tanks or bombs, as they were used to spot artillery fall from the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth. One Hellcat is in its takeoff roll (note propeller tip spiral contrail), while another is ranged and ready to follow and half a dozen others warm their engines on the starboard deck edge. Being a short escort carrier of 500 feet, Ameer and other Ruler-class ships required that the takeoff run begin at the round-down on days of little wind. Photo: Imperial War Museum

During the Third Battle of Arakan, an 804 Squadron Hellcat comes to a stop over the deck edge and into the catwalk of HMS Ameer. Armourers on both wings extract the aircraft’s ammunition while white-capped officers decide the best way to salvage the aircraft and get the deck back in operation. Photo: Imperial War Museum

An 804 Squadron Hellcat (B8-W), which had been seriously damaged when it spun around and went over the edge of the flight deck on the port, getting tangled in Ameer’s Oerlikon gun sponsons. Before she was sent into the water, her ammo compartments were opened and emptied. Photo via Mission4today.com

Not all sailors were aboard Ameer for the care and feeding of aircraft. Some, like these anti-aircraft gunners, were there to bring down aircraft—of the Japanese variety of course. Every gunnery rating in this photograph was from Newfoundland, which was its own country during the Second World War—one with a deep maritime tradition. Front row, left to right: A. Blundon, Musgrave Town; Leading Seaman N. Hodder, Gander Bay; P. Downey, White Bay. Second row: P. Dinn, St John’s West; R. Davis, Grand Falls; F. Philpot, White Bay; N. Rideout, Conception Bay. Third row: M. Tucker, Thornburn Road, St John’s; C. Connors, Grand Falls; J. Murphy, Kilbride, St John’s West; M. power, New Gower Street, St John’s; W. Morgan, Port de Grave; F. Puddester, Northern Bay. Back row: W. Russell, Bonavista; J. Barry, St John’s West; N. Webster, Popes, Higher Trinity Bay; H. White, Godroy Valley; M. Wright, Deer Lake; K. Janes, Deer Lake. Photo: Imperial War Museum

From March through June, she undertook a period of training and then continued her extraordinary combat career, participating in Operations BALSAM (southern Malay Peninsula), COLLIE (Malay Peninsula with 896 Squadron), LIVERY (Kraa Peninsula, Malaysia with 804 Squadron) and Operation CARSON (attacks on airfields on Penang and Medan areas.

On 15 August, the crew of Ameer got the messages to suspend operations, while in harbour at Trincomalee. Following enthusiastic celebrations in Trincomalee’s harbour, she returned to operations covering landings (unopposed Operation ZIPPER) to take Malayan targets and the surrender of the Japanese.

Ameer’s combat career was extensive compared to the average Ruler-class escort carrier, but when it was over, it was over. Following her last sorties as part of ZIPPER, she was sent home to the Clyde, arriving there mid-November. By mid-January 1946, Ameer returned to Norfolk and was returned to the US Navy.

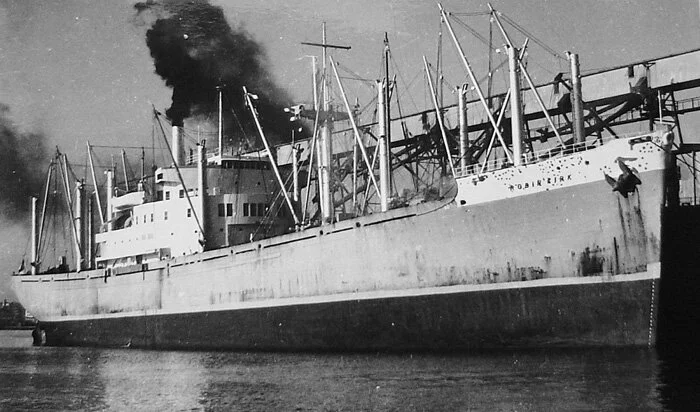

She was sold in September of that year to be converted to mercantile service with the Robin Line as SS Robin Kirk, serving well until she was broken up at Taiwan in 1969.

After her decommissioning, the hull that once went to war as HMS Ameer was rebuilt in 1948 as SS Robin Kirk of the Robin Line. She was stripped down to the bilges and built up again as a passenger/cargo ship. She went to war four more times as Robin Kirk between 20 August and 27 December 1950—bringing supplies in support of the Inchon Landing and the Hungnam redeployment in the Korean War. The Robin Line was later purchased by the Moore McCormack Line in 1957 and she ended her days on general cargo routes from the East Coast of the United States. She was broken up for scrap in Kaohsiung, Taiwan in 1969. Photo: NavSource.org

HMS Atheling (Pennant Number D51)

HMS Atheling anchored in the Firth of Clyde after her first crossing of the Atlantic. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In early June 1942, welders and rivet men of the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding laid down the steel for the keel of a new C3 freighter hull, which was purchased by the United States Navy for completion as an escort aircraft carrier to be named USS Glacier Bay. Glacier Bay was launched three months later and began dockside completion work at the Bremerton Navy Yard. She was offered to the Royal Navy during this work period under the Lend-Lease program, but work continued and she was commissioned USS Glacier Bay ten months after she had slipped down the ways. She sailed for Vancouver, British Columbia where, two weeks later, she was handed over to the Royal Navy. Three months after that she was commissioned as HMS Atheling, the Middle English name given to a prince or nobleman in Anglo-Saxon England.

Before she left Vancouver, Atheling went through a series of modifications to make her fit for service in the Royal Navy. This took until late November 1943. She then shaped a course from the Panama Canal, entering the locks at Balboa on 6 December. By 18 December, she was in Norfolk, Virginia taking on a large number of both Lend-Lease and squadron aircraft. Of the former, she had 18 Avengers, 8 Hellcats and 10 Harvards (nearly all on her flight deck), while of the latter she had the 18 Corsairs of 1836 Squadron, all bound for the United Kingdom.

HMS Atheling underway with a deck load of Lend-Lease aircraft en route from Norfolk, Virginia to New York City to join a convoy for the first crossing. Her deck holds 17 Grumman Avengers (already in South East Asia Command roundels), 8 Hellcats at her stern and 10 North American Harvards forward, while in her hangar deck spaces she carries the 18 Corsairs of 1836 Squadron—all bound for Great Britain. Photo: US Navy via Wikipedia

HMS Atheling moored at Greenock on a sunny day on the Clyde. This would have been after 10 January, when having disposed of her cargo of Lend-Lease aircraft in Belfast, Northern Ireland, she dropped anchor in the Clyde for the first and only time. Photo: Imperial War Museum

She then moved up to New York and awaited departure of the next fast convoy which left on New Year’s Day 1944. Eight days later, she made Belfast, Northern Ireland where she craned off her aircraft. Once these were dispatched, she crossed the North Channel and entered the Firth of Clyde where she would undergo additional modifications as a fighter carrier. A month and a half later, Atheling embarked the aircraft for Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm squadrons for transit to the East Indies—822 Squadron (12 Fairey Barracudas), 823 Squadron (12 Fairey Barracudas), 1837 Squadron (14 Corsairs and pilots) and 1838 Squadron (10 Corsairs and pilots). Atheling raised anchor at the beginning of March, and made Colombo, Ceylon via the Suez Canal late in April, having deposited the Barracudas at Madras, India and the Corsairs elsewhere in Ceylon.

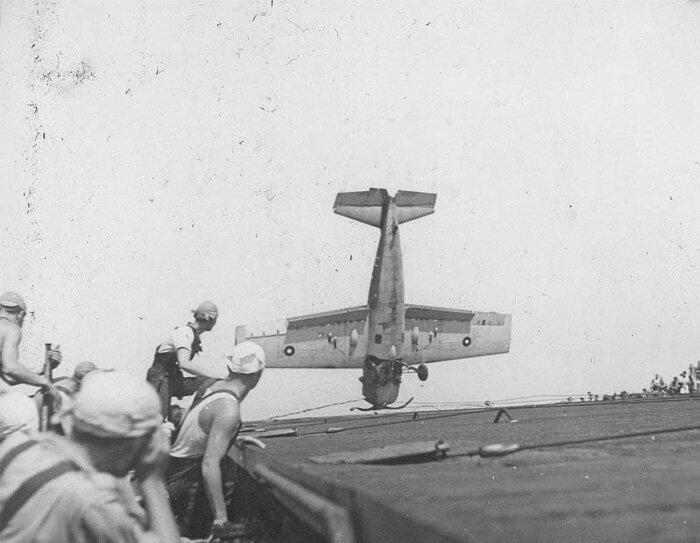

A Fairey Barracuda (from either 822 or 833 Squadron) leaps from the very end of Atheling’s flight deck, recently painted with her new “A” deck code. With its odd Fairey–Youngman flaps/dive brakes and high T-tail, the Barracuda was unique among British-designed naval aircraft. However, like all British carrier aircraft, the Barracuda was not capable of being catapulted from Atheling’s accelerator. After the war, Barracudas saw service with the Royal Canadian Navy aboard HMCS Warrior. Photo: RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

Once in Colombo, Atheling was assigned to the 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron, conducting operations protecting convoys in the Bay of Bengal. To do this, she embarked the Seafires of 889 Squadron and the Grumman Wildcats of 890 Squadron. She carried out Combat Air Patrols and Spare Deck duty during Operation COUNCILLOR in concert with HMS Illustrious, but not long into the operation, she was deemed too slow to work with the big fast fleet carrier. She disembarked her fighters by the end of July and returned to convoy or trade protection duty, this time with the Fairey Swordfish of 818 Squadron. During this time, she had undertook aircraft carrying duties between Ceylon and South Africa—taking the Corsairs of 1838 Squadron to Cape Town and bringing back Hellcats and Avengers to Ceylon.

On June 29 1944, a Seafire piloted by New Zealander Sub-Lieutenant John D. Chittenden struck and broke through Atheling’s wire barrier and collided with another parked Seafire, taking both over the side. The accident also killed another pilot, New Zealander, Sub-Lieutenant Royden T. Bisman, and three other maintenance men (Norman Brechin, Ronald Milton and Herbert Patrick) who were working on aircraft forward of the barrier. Here, Atheling’s commander, Captain Agnew oversees the burial at sea of two of the dead later that day. Photo: Charles Kelly via RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

A Grumman Wildcat (JV508) of 890 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm, misses the arrestor wires aboard HMS Atheling and strikes the wire barrier, pitching hard up on its nose. The carrier was operating as part of the East Indies Fleet at the time—15 May 1944—working up as a fighter carrier. The Wildcat had arrived on board just two days before from RNAS Puttalam near Colombo, Ceylon. Photo: John Vallely Collection via RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

A superb shot of HMS Atheling steaming along somewhere in the Far East, with a Corsair just coming up on the aft elevator. This is the last of a series of images taken from an orbiting Fairey Swordfish aircraft. In all of them the aft elevator shaft is open, with the sailor in the whites standing by the forward elevator. Note her Deck Code “A”. Photo: Charles Kelly via RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

Sailors cheer on crew mates in a potato sack race during a sports day aboard HMS Atheling, obviously in southern climes. Not sure which is the finish line, but the fellow at the back has tripped and looks to be heading for some sort of physical punishment and hilarity for the spectators. Photo: RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

It seems ferrying was what she was best suited to, and in early October 1944, she was nominated as the East Indies Fleet ferry carrier, likely because of her slow speed. In early December, she sailed for Sydney, Australia in company of HMS Battler and other escorts, with a load of aircraft. At this time she was on loan to the United States Navy specifically for ferrying and she left Sydney for Pearl Harbor, arriving there on Valentine’s Day 1945.

For the next six months, Atheling ferried aircraft and personnel across the Pacific from the US West Coast and transported wounded servicemen and other passengers home to the USA. Following this and the surrender of the Japanese she was returned to the Royal Navy in September of 1945, returning to Plymouth, England on 16 September for conversion to a trooping vessel. This meant converting the hangar deck to barracks, complete with messes and other facilities not normally found on a carrier. Her first trooping voyage took her from Plymouth to Ceylon, New Zealand and Australia to return troops and move some aircraft. She remained in this role until the end of the year when she was handed back to the United States Navy at Norfolk in December.

From January to August of 1945, Atheling was detached from the Royal Navy to the US Navy for ferrying duties, carrying aircraft from the United States to the South Pacific via Pearl Harbor. This photo from that time period shows her deck packed with Corsairs, most of which do not appear factory-fresh.

Atheling at anchor in December of 1945 in the harbour of Melbourne, Australia on a blustery day during her first trooping voyage. We can see the addition of life rafts on angled slides lining flight deck aft of the island. As well, we can see rafts along the edge of the forward flight deck round-down. Photo: Allan C. Green via NavSource.org

The ship that was once Atheling may never have had an illustrious combat career having been more of a ferryboat, but the life she was granted after being struck off charges far more glamorous than all the other Ruler-class carriers which, if they were lucky, got to live on as a cargo/passenger freighter. Atheling/Glacier Bay was sold to the Lauro Line and converted to the luxury liner S.S. Roma, working the Italy to Australia/New Zealand route. She did her new duty with typical Italian style and flair for twenty years before being scrapped in 1967 due to a diminished demand for ocean liner travel.

Atheling slides gracefully out of Valetta Harbour in Malta. On certain websites, this is attributed to her voyage from the United Kingdom to Ceylon via the Suez Canal in March of 1944. The problem here is that her paint scheme lacks the dazzle paint camouflage she had in 1944. The fact that she shows no aircraft on her decks and has extra life rafts tied along her flight deck clearly indicates that this image is postwar when she was committed to trooping duties, bringing service personnel and civilians back to the United Kingdom. Given that there are few sailors or passengers on the deck (there seems to be a group of sailors on parade just forward of the open elevator), this is possibly an outbound voyage from Plymouth to the Far East to collect passengers, after getting a fresh coat of paint. The previous photo shows that on her first trooping voyage, she was in rough shape in the paint department in December, so this image was likely taken in 1946. Photo: NavSource.org

A nice shot of Atheling after the war with her camouflage paint removed and in her trooping configuration.

Following her hand-off to the United States Navy, HMS Atheling (the former USS Glacier Bay) was added to the Reserve Fleet in Jacksonville, Florida, tied up and languishing until sold off in 1950 to the Italian Lauro Line along with the former HMS Fencer. Instead of being converted to mercantile use as a freighter, Atheling was converted to the beautiful luxury liner SS Roma (with Fencer becoming the identical SS Sydney). Roma (ex-Atheling) was broken up in Italy in 1967. Her sister ship Sydney was renamed Roma and served Lauro as a cruise ship for another two years, then sold off to various cruise lines until she met her end at the hands of Italian breakers in 1975. Photo: ssmaritime.com

HMS Begum (Pennant Number D38)

HMS Begum at Greenock on the Clyde on 6 February 1944, shortly after her first crossing of the Atlantic from New York City where she had taken on board 24 Corsair aircraft for use by 1837 and 1838 Squadrons. Following her arrival at Greenock, she had some conversion work done on the Clyde. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Most of the escort carriers of the United States and Royal Navies of the Second World War were built in America’s Northwest Coast. There were a number of shipyards participating in keel-up construction as well as post-launch fit up and finishing. Most of the meant-for-US Navy carriers that were then assigned to the Royal Navy through the Lend-Lease programs were further modified for Fleet Air Arm requirements in British Columbia, Canada.

One of the major shipbuilding enterprises in Washington was the city of Vancouver, across the Columbia River from Portland, Oregon, about 80 miles from the Pacific Ocean. In January of 1943, Vancouver’s Kaiser Shipyard laid down the keel for a Casablanca-class escort carrier, to be named HMS Chastiser. After her launch in April, her name was changed to HMS Begum, a Ruler-class carrier named for a Muslim female royal or aristocratic title from Central or South Asia—the wife of a “Bey” or “Beg”. At the last minute, the US Navy determined that Begum would remain in their service and she was commissioned as USS Natoma Bay.

Instead, the name Begum was transferred to an already completed Bogue-class escort carrier named USS Bolinas. On 2 August 1943, the day she was transferred to the Royal Navy, Bolinas was commissioned as HMS Begum, Royal Navy.

Upon completion of her acceptance trial, Begum made for Esquimalt, British Columbia for modifications for Royal Navy service. These were a large number of alterations, the largest of which was the lengthening of her flight deck. In late December of 1943, work was completed and she made revolutions for Panama, the Canal and eventually Norfolk, Virginia, where she took on a cargo of Lend-Lease Corsairs belonging to 1837 and 1838 Naval Air Squadrons. In addition, she embarked the pilots, other personnel and equipment of said squadrons, both of which had recently completed their work-ups at Naval Air Station Brunswick, Maine. From Norfolk, Begum made New York on 16 January 1944.

In New York, Begum embarked more stores and 194 military passengers as well as 45 civilians, including a group of British school children who had previously been evacuated to Canada for safety reasons and who were now going home. Begum crossed the Atlantic safely in the company of HMS Trumpeter and, after disembarking her passengers in Liverpool, sailed for Greenock, Scotland, dropping anchor in the Clyde, having flown off the aircraft of 1837 and 1838 Squadrons en route.

By the end of February, she was at Royal Naval Air Repair Yard in Belfast, Northern Ireland loading aircraft. Here she took aboard the aircraft of four squadrons—the Hellcats of 1839 and 1844 Squadrons and Fairey Barracudas of 815 and 817 Squadrons. While the pilots and personnel of these squadrons took passage aboard separate troopships, Begum set sail on 3 March 1944 for Trincomalee to join the swelling air ranks of the Eastern Fleet. She travelled in company with the escort carrier HMS Atheling, heavily escorted in convoy to Alexandria, Egypt.

Inter-ship sports and rivalry were keys to keeping up morale in faraway places and under the stress of war. Hockey, boxing and football were favourites of the more sporting crew members like these young men from Begum’s soccer team, photographed in May of 1944, likely at Colombo, Ceylon. Photo: https://sites.google.com/site/leselevettcjx131840/indian-ocean

At the end of May 1944, Begum was joined by the Grumman Wildcats and Avengers of 832 Composite Naval Air Squadron. For most of June, Begum worked up her new air element which would be responsible for anti-submarine sweeps against German U-boats in the Indian Ocean, mainly in the area of the Seychelles and near Madagascar. She made five operation U-boat sweeps in the Indian Ocean, commencing in mid-June and lasting until the end of the year.

A Grumman Avenger of 832 Squadron, flown by Sub-Lieutenant J.E. Randall, misses the trap and strikes the first cables of the wire barrier aboard HMS Begum. This was one of three flying accidents that occurred with 832 Squadron on 1 June 1944. 832 Squadron, a composite squadron flying both Avengers and Wildcats and previously assigned to Illustrious for attacks on Surabaya, joined Begum in Colombo in late spring of 1944. Photo via MaritimeQuest.com

Begum’s deck crew work quickly to disentangle Sub-Lieutenant Randall’s Grumman Avenger (serial number JZ231) from the barrier wires on 1 June 1944. A second Avenger can be seen making an approach from the port beam in the background. Crews needed to clear away the snagged aircraft and reset or repair the barrier wires before attempting to take on another aircraft. Photo: MaritimeQuest.com

Scanning this photo, we see an identical weather situation and similarly dressed deck crew as in the previous image depicting Randall’s crash. It is likely that this was the same day (1 June 1944) and that this is possibly the Avenger piloted by Lieutenant F.L. Low, which had struck Begum’s round-down and broken its back—clearly the situation that befell this Avenger. Photo: MaritimeQuest.com

An 832 Squadron Grumman Avenger warms up on Begum’s flight deck, while another executes a high speed flypast for the photographer. 832 Squadron, first formed in 1941 at Lee-on-Solent, was a Wildcat/Avenger composite squadron that joined Begum in 1944 and served aboard her until its disbandment in February 1945 in the United Kingdom. Photo: MaritimeQuest.com

It was time for refit, and she was scheduled for work in the United Kingdom, so she sailed with passengers and the personnel of 832 Squadron, making her way to the Clyde, arriving in late February. Upon arrival, 832 Squadron was permanently disbanded and she went to the docks for conversion to ferry-specific duties. By the end of March, Begum was ready to shake down in the Irish Sea. Following certification she made for RNARY Belfast to take on board a small load of Vultee Vengeance TT.IVs and Supermarine Sea Otters (development of the Walrus) and sailed for Gibraltar and on to Colombo via the Suez Canal.

She was assigned ferry duty with the Pacific Fleet and offloaded her aircraft on the Admiralty Island of Ponam, off the coast of Manus. The former Japanese airfield took up half the total area of the sliver of an island. Following this, she sailed for Australian waters to offload the last of the Sea Otter flying boats in Sydney.

HMS Begum with two Grumman Avengers from 832 Squadron ranged on her flight deck. Photo: NavalHistory.net

After the single lengthy ferry mission, she was attached to the Pacific Fleet as a Deck Landing Training Carrier, landing on many types of carrier aircraft then in use with the British Pacific Fleet. Following this she sailed back to Trincomalee to join a carrier task force as part of Operation ZIPPER, the invasion of Malaya and the recapture of Singapore. Unfortunately, as Begum steamed from “Trinco”, she suffered serious structural damage when she struck a submerged object and was withdrawn from the operation.

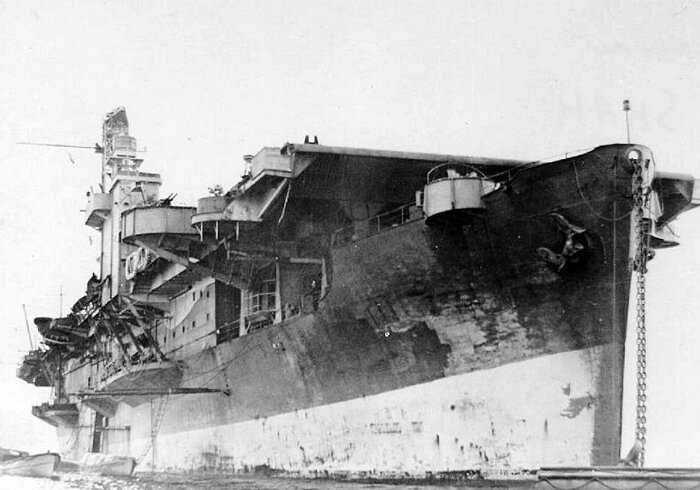

She was given a temporary repair and sailed for Bombay for comprehensive repairs. It was while she was in Bombay that the Japanese surrendered. She was ordered to return to Great Britain upon completion of the work to be decommissioned. She took servicemen home with her as passengers, and was stripped of her Royal Navy equipment. She left the Clyde with a skeleton crew in mid-December 1945, sailing to Norfolk. The crossing was not without incident however. Heavy weather and high seas brought about the collapse of the forward flight deck’s structure and it came adrift. Her small ship’s crew made temporary repairs and she made Norfolk on Christmas Day, 1945

Begum was taken back by the US Navy and sold for conversion to mercantile service, becoming SS Raki in 1948 and remained in service until 1966 whence became SS I Yung. She was finally broken up in Taiwan in 1974.

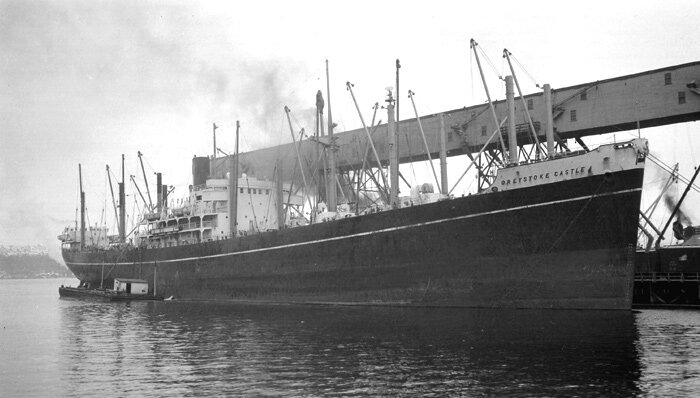

In the summer of 1946, the carrier that had once been HMS Begum was sold off for conversion to mercantile service. The work was done and she was sold to the Netherlands Steamship Company and worked the cargo circuit as SS Raki (above, fully loaded) until 1966 when she was sold and renamed SS I Yung until 1974 when she met the breaker’s torch in Taiwan. Photo: home.knp.nl

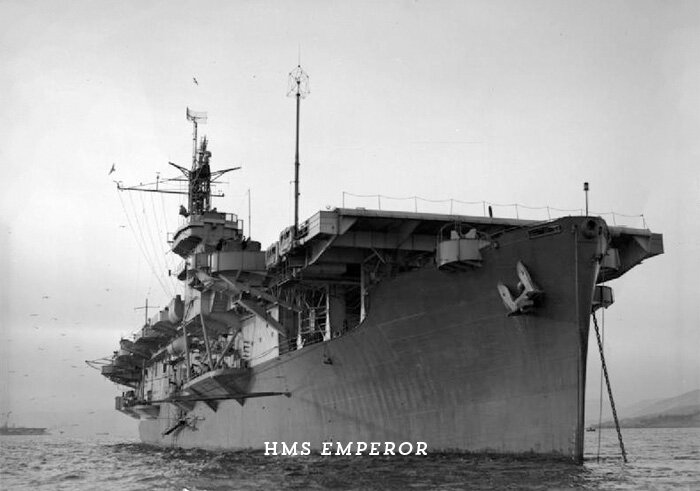

HMS Emperor (Pennant Number D98)

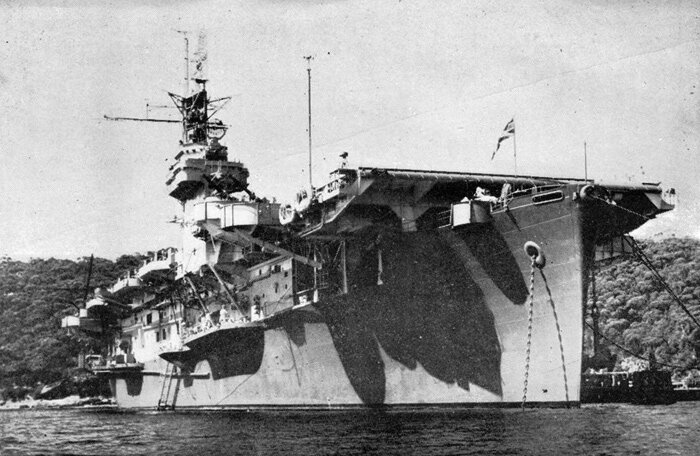

HMS Emperor lies in stately repose on the Clyde River with her long-range radio mast raised and safety rails up. Photo: Wikipedia

Like many of her sister escort carriers in service with the Royal Navy, HMS Emperor was laid down at the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding yard and meant for service with the United States Navy. She was laid down as USS Pybus in June of 1942 and was launched in October. Pybus’ systems and finishing were completed by the beginning of June 1943 and she entered a short period of workup before sailing on her first voyage, to San Diego and then on to Pearl Harbor with a ferry cargo of aircraft.

By the time she left Pearl, it had been decided she would be transferred to the Royal Navy, so she transited the Panama Canal and headed north on the American East Coast to New York, where she quickly transferred to the Royal Navy and commissioned as HMS Emperor. In New York’s Brooklyn Navy Yard, she took on another load of aircraft to ferry to the Clyde and joined Fast Convoy HX 253 at Halifax for the crossing.

After USS Pybus was decommissioned and entered service with the Royal Navy as HMS Emperor, she left New York bound for Greenock, Scotland with a deck cargo of Grumman Hellcats. Forced to take a much more northerly route to avoid submarines, she ran into a blizzard, fog and pack ice off the coast of Newfoundland. Photo: Imperial War Museum

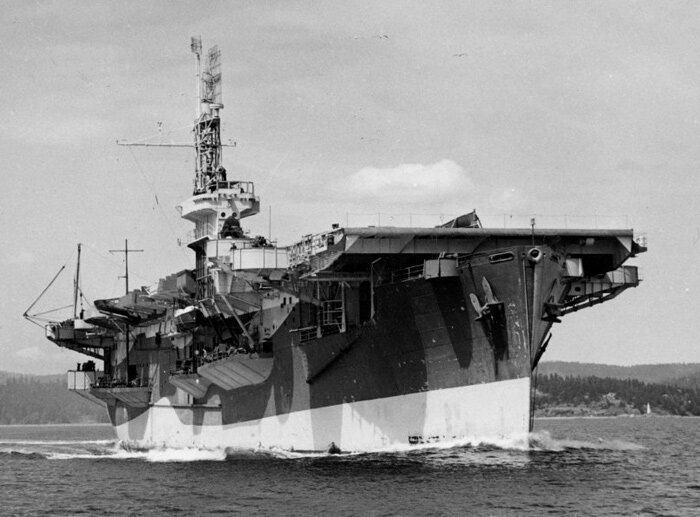

HMS Emperor rests at anchor at Greenock, Scotland in the Upper Firth of Clyde in January 1944. She had arrived in Great Britain and the Clyde in September 1943, whereupon she was then moved to Belfast for further modifications for Royal Navy Service. This photo was taken upon her return to the Clyde where and when she began workup for operational service as an escort carrier in the Western Approaches to Great Britain. I’ve always tried to see the purpose in what sometimes may seem random and abstract dazzle painting on ships of the Second World War. The darker silhouette shape on Emperor’s starboard side definitely brings to mind a freighter angled away from the viewer, possibly intentionally done this way to confuse U-boat captains in dodgy weather. Photo: Imperial War Museum

After making the Clyde at the beginning of September, Emperor was assigned to the Western Approaches Command and sent to Belfast, Northern Ireland to be modified to Royal Navy standards for service with Fleet Air Arm aircraft. By the middle of December 1943, she was working up in the Irish Sea with the aircraft of 804 and 800 Squadrons.

In January 1944, Emperor, with 800 and 804 Squadron’s Hellcats, steamed for Norfolk, Virginia, escorting a westbound convoy. She returned to England via Argentia, Newfoundland where she joined an eastbound convoy out of Halifax. Emperor departed the convoy at Ireland and arrived again on the Clyde where she disembarked her squadrons. She collected her squadrons again in early March 1944 and sailed for the Home Fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow.

HMS Emperor rolls heavily in nasty North Atlantic Weather. Four Hellcats are lashed securely with their engines and cockpits covered in tarpaulins to avoid sea water getting into the important bits. This looks to be a right miserable scenario when no one in their right mind should be out on this slippery deck, yet a sailor can be seen checking tie downs on the Hellcat on the left, with possibly a second man at the tail of the fighter. Photo: Imperial War Museum

HMS Emperor’s destroyer escort, HMS Javelin, pitches heavily in frigid Norwegian waters as a blizzard descends on the task group. A fuelling hose can be seen draped over from her forecastle as she takes on oil from Emperor. The sailors tasked with getting this line aboard Javelin were surely at great risk. The date was 14 May 1944 and Emperor was in the company of 6 Home Fleet destroyers as well as the escort carrier HMS Striker, and the Royal Navy cruisers Sheffield and Royalist for attacks on shipping near the port of Rorvik, halfway up the coast of Norway. Photo: Imperial War Museum

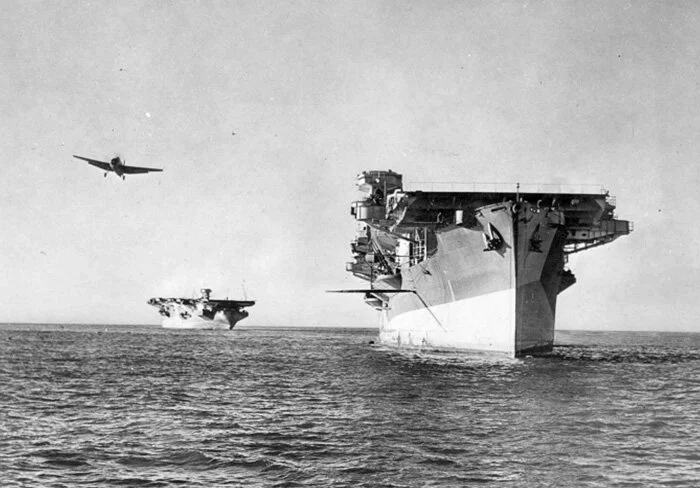

In the spring, Emperor joined other fleet and escort carriers as part of Operation TUNGSTEN, to conduct strikes against the German battleship Tirpitz which was holed up deep in a Northern Norwegian fjord known as Kaafjord. Despite the massive effort to take out Tirpitz, little damage was done. Following a short break at Scapa Flow, she joined other Royal Navy elements of Operation PLANET, a second attempt to destroy Tirpitz, which fizzled because of inclement flying weather. When the weather improved, she was employed as part of Operation RIDGE ABLE attacking coastal shipping near Bodø and Rorvik, Norway. She continued on offensive operations until the middle of May when she was sent back to Western Approaches Command. Until the middle of the summer of 1944, Emperor conducted cover and escort duties with convoys transiting the Approaches as well as fighter cover for Operation NEPTUNE in support of D-Day.

HMS Emperor (left) and HMS Striker, seen from the hangar deck of HMS Puncher, plough though heavy seas off the northern coast of Norway and above the Arctic Circle during Operation TUNGSTEN in April of 1944. Life aboard a top-heavy, rolling escort carrier in freezing temperatures could be a misery. Within six months however, Emperor would be in the Mediterranean Sea and then the Indian Ocean. Photo: Imperial War Museum

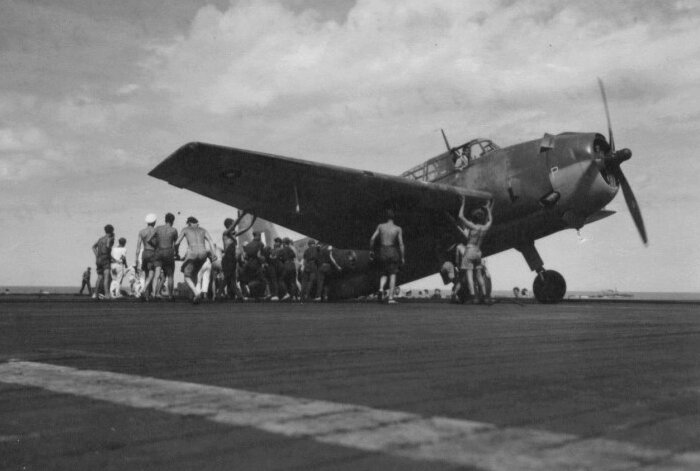

During her short military career, HMS Emperor saw action in some seriously varied climates, from sweltering Ceylon to Arctic waters off the Norwegian and Barents Seas. She was deployed in March of 1944 along with sister carriers HMS Searcher, Pursuer and Fencer to defend a Russian convoy and to attack the German battleship Tirpitz holed up deep in a Norwegian fjord well above the Arctic Circle (Operation TUNGSTEN). Here we see Hellcats warmed up and ready to launch in some very inhospitable weather. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A tradition since aerial bombing began, ground crews love to chalk a message for the enemy on bombs to be delivered on the next mission. It was a way for ordnance men and ground crews to feel part of the fight. Here, an armourer aboard HMS Emperor, possibly a Londoner, sends an ironic “An Instalment [sic] from London” message on an 800 Squadron Hellcat to the Germans who would soon be on the receiving end during Operation NEPTUNE, the D-Day invasions. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Hellcats from HMS Emperor ready for launch off the coast of France during the Normandy invasions as part of Operation NEPTUNE (D-Day invasions). In the middle-ground, a deck hand chocks the next in line, while in the background, deck handling crews wrestle a Hellcat forward with its propeller turning. With so many sailors attending the Hellcat, one wonders if there is some sort of issue with the wing folding. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Hellcats from HMS Tracker and Emperor fly across the Emperor’s wake to take up combat air patrol duties over convoys in the Southwestern Approaches (Bristol Channel, Celtic Sea and open water off southwest Ireland) in order to counter any U-boat attacks that may be launched from there against the Normandy invasion fleet (some of the aircraft have D-Day stripes). On deck, a second wave of “wasp-winged” Hellcats prepares for launch. On 18 June, 800 Squadron absorbed the Hellcats of 804 Squadron and shortly thereafter set sail for the Mediterranean Sea aboard Emperor. 804 Squadron would eventually reform in South Africa in September and board HMS Ameer. Photo: Imperial War Museum

She then sailed for the Mediterranean Sea for more offensive operations as part of Operation DRAGOON, the Allied invasion of the South of France. For the next few months she took part in offensive operations around the Mediterranean. By December, she was back in the UK getting a refit. In February of 1945, after her post-refit workup, Emperor shaped course for Trincomalee, Ceylon to join the Eastern Fleet’s 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron along with her sister escorts Khedive, Begum, Empress, Shah, Slinger, and Speaker—a formidable Fleet Air Arm weapon if there ever was one. Emperor conducted extensive offensive operations with the squadron, including Operations SUNFISH, DRACULA, DUKEDOM, COLLIE, ZIPPER and JURIST

HMS Emperor steams slowly over the Bitter Lakes entry to the Suez Canal en route to Trincomalee, Ceylon in February of 1945 to join the 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron of the Eastern Fleet. She is seen here beautifully framed by two twin 4.5 pound gun turrets on HMS Indomitable, a Royal Navy Illustrious-class fleet carrier. The 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron would include His Majesty’s escort carriers Emperor, Begum, Empress, Shah, Ameer, Khedive, Slinger and Speaker. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Following the surrender of the Japanese, Emperor continued on with the Eastern Fleet until October when she sailed for the United Kingdom, stopping in at Colombo and Bombay on the way. She was paid off and sailed with a skeleton crew to Norfolk and handed over to the US Navy, sold for scrap and broken up by May of 1946

A United States Navy Hellcat takes off from the Royal Navy’s HMS Emperor during Operation DRAGOON, the Allied invasion of the South of France, two months after D-Day. The reason that the aircraft was even on Emperor is not known. It is possible the pilot was aboard for a conference or possibly had landed on Emperor mistakenly or in an emergency. The Hellcat was from VGF-1 assigned to USS Tulagi, an American escort carrier. Emperor was operating during DRAGOON with the escort carriers Attacker, Hunter, Khedive, Pursuer, Searcher, and Stalker as well as the American escort carriers Tulagi and Kasaan Bay. Photo: Imperial War Museum

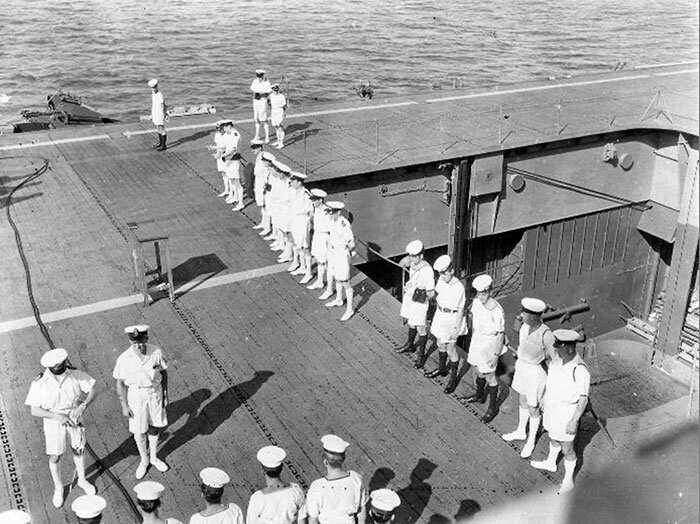

At the end of the war, HMS Emperor enters Singapore harbour in style for the surrender of the Japanese with a neat row of 800 Squadron Hellcats, with propellers aligned to perfection, and flanked by a turnout of all hands in tropical whites. Emperor was part of Operation ZIPPER with her sister carriers Ameer, Empress, Hunter, Khedive and Stalker, tasked to reoccupy Singapore. The task force left the British Eastern Fleet home base at Trincomalee, Ceylon on 4 September 1945 and sailed into Singapore harbour two days later. After leaving Singapore, she sailed for India where she bid farewell to her 800 Squadron aircraft and pilots. Photo: RoyalNavyResearchArchive.org.uk

HMS Empress (Pennant Number D42)

HMS Empress lies quietly at anchor at the Firth of Forth, with the Kincardine Bridge possibly in the right distance. She was here for nearly half a year, starting in May of 1944, undergoing repairs and modifications. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In September of 1942, the Seattle–Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation laid down the keel for a mercantile ship based on the C3 hull design which was then requisitioned, and the hull completed and launched as the escort carrier USS Carnegie. Half a year later, her kitting out was completed and, after a short voyage to Vancouver, British Columbia, she was handed over to the Royal Navy to be commissioned as HMS Empress of the Ruler Class.

The work to modify her to Royal Navy standards was completed by Burrard Dry Dock Co. by the beginning of December 1943. During this long period of modification work, her crew came aboard and began working up with systems and procedures.

In January of 1944, Empress began training with the Avengers of 850 Naval Air Squadron, practicing deck landings and launches while the ship steamed up and down Georgia Strait. Finally, nearly a year and a half after her keel was laid, Empress left Vancouver with 850’s Avengers aboard, bound for the Clyde by way of San Francisco, San Diego, Panama Canal, Norfolk and New York—the traditional ports of call for a West Coast-built escort carrier of the Royal Navy on her maiden voyage.

After some turbine trouble that slowed her progress and then transiting the Panama Canal, she joined the escort carriers HMS Speaker and USS Tulagi and with a covey of both RCN and USN escort ships, sailed in convoy for Norfolk. After a brief stay in New York, where she picked up some UK-bound war children, she crossed in convoy with Speaker and made for the Clyde, flying off her 850 Squadron “Turkeys” on arrival and dropping anchor on 8 April 1944.

On her first transatlantic crossing from New York to the Clyde, Empress carried Avenger aircraft on her hangar deck, but a more precious cargo on the mess decks. At the outset of the war, many mothers and children were evacuated to America with Britain facing invasion. By 1944, many wanted to return. On her crossing, Empress brought home more than 50 women and children. Here, “foster father” officers aboard Empress check in on a cabin used by young boys going home to their parents. One can only imagine the excitement for these young lads crossing the ocean on a carrier. Photo: histarmar.com.ar

Her first assignment was with Western Approaches Command just three days later—a brief period of Deck Landing Training with 768 Deck Landing Training Squadron, a multi-type shore-based squadron used for deck training pilots of the Fleet Air Arm. Shortly thereafter, she took a berth at a Clyde dockyard and then on to a Rosyth dockyard for repairs, rectification and modification. This period of work took until late summer. Following this, Empress returned to deck landing training with 768 Squadron, which was then based in Royal Navy Air Station Ayr, south of Prestwick on the shores of the Firth of Clyde.

In November of 1944, off the west coast of Scotland, newly arrived Empress played host to several naval air squadrons looking for a deck to train on—Swordfish, Fireflys and Seafires. Here, a Seafire snags a wire and bounces high. As a carrier based fighter, the Seafire’s design was a compromise and suffered many losses through structural damage caused by heavy landings on carrier decks: a problem that continued even after strengthening introduced by the Mk II. The Seafire had a narrow undercarriage track, which meant that it was not well suited to deck operations. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Two days after O’Driscoll’s mishap (next photo), Sub-Lieutenant Bounce (appropriate name) ended up in the port catwalk when his Fairey Swordfish veered violently to the left on landing, coming to rest before hitting the barrier (wires in middle ground). In the foreground, deck crews scramble to run hoses out to the damaged Swordfish in case of fire. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Aboard HMS Empress, a Fairey Firefly has been seriously damaged in a landing accident during a training period. The Fleet Air Arm squadrons that were officially attached to Empress were either Hellcat squadrons (888, 804, and 896 Squadrons) or Avenger squadrons (850 and 845 Squadrons). In November of 1944, the flight deck of Empress was used to train the Firefly crews of 1772 Naval Air Squadron. On 25 November, Sub-Lieutenant I.T. O’Driscoll landed aboard, but his tail hook bounced over all the arrestor wires and his Firefly (Z2022) struck the barrier heavily. Photo: Imperial War Museum

During the last two months of 1944, she continued Landing Training with the Fireflies from 1772 Squadron and Fairey Swordfish from 766 Squadron, then ceased DLT duties and by Christmas was nominated for service with the 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron of the Royal Navy’s East Indies Fleet. As 1945 began, she sailed in convoy to Gibraltar with a load of Grumman Hellcats. By late January, she was in Cochin, India offloading her Hellcats before making for Trincomalee and the home harbour of the British East Indies Fleet. She arrived at “Trinco” in early February, having landed on the Avengers of 845 Squadron before entering the harbour. Here she would join her sister escort carriers Khedive, Begum, Emperor, Shah, Ameer, Slinger and Speaker. She began operational activity almost immediately, embarking recce Hellcats from 888 Squadron and a Hellcat detachment from 804 to secure anti-submarine sweeps from 845’s Avengers.

Throughout 1945, Empress participated in a series of combat operations until September. First, it was Operation STACEY, a series of photo recce ops over Penang and the Kra Isthmus, in the company of Ameer and escort ships as part of Force 64. This lasted until the end of March 1945. In April, Empress joined Khedive and other escorts (including the French battleship Richelieu) in Operation SUNFISH, another recce operation, this time of Port Swettenham and Port Dickson in Malaya. During this operation, Empress had two near misses with kamikaze aircraft, one exploding only 200 metres from her port side.

Standing on the bridge of the HMS Empress, Lieutenant John Myerscough, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, waves to the photographer. He had just reported to Empress’ captain with the details of how he had shot down a Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar whilst leading his section of Hellcat fighters giving air protection to a Task Force of the East Indies Fleet. It was the first Japanese aircraft shot down by an Empress-based fighter and the ship’s artist wasted no time in recording the event by painting the Japanese Navy flag and an Oscar aircraft silhouette alongside. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In late April and May, it was Operation BISHOP, an air cover/naval decoy operation in support of Operation DRACULA, the invasion of Rangoon. The cover for DRACULA was provided by air attacks and gunfire bombardments on Car Nicobar, the northernmost of the Nicobar Islands group, and the harbour at Port Blair in the Andaman islands group. There were attacks on Car Nicobar and Fort Blair on 30 April, with a second bombardment of airstrips at Car Nicobar on the morning of 1 May, and at Port Blair on 2 May. On 6 May, after a short bombardment of the Japanese anti-aircraft defences, aircraft from Empress and Shah, which were part of the 21st Carrier Squadron and escorted by the destroyers Virago, Tartar and Nubian, attacked shipping in the harbour of Port Blair.

After the first week of May 1945, Empress joined Emperor, Hunter, Khedive and Shah in Operation DUKEDOM, the search for the Japanese heavy cruiser Haguro and the destroyer Kamikaze which had been acting as armed supply ships for the Japanese garrisons at Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. Getting wind that Empress and the others and their escorts had sailed from Trincomalee to intercept them, the Japanese Imperial Navy ordered the Haguro and her consorts to return to Singapore. Aircraft from Empress were the only ones to engage Haguro as she ran for home—a staggeringly long-range flight of 530 miles from launch to Haguro. When, on 14 May, Haguro and Kamikaze made a second attempt, they were spotted and, on 15 May were surrounded by a Royal Navy destroyer flotilla that sank Haguro in the now famous Battle of the Malacca Strait.

A nice shot of rocket projectile-equipped Grumman F6F Hellcat JX688 of 896 Squadron attached to the catapult aboard Empress in 1945. The catapult “bridle” was the cable that attached the aircraft to the catapult shuttle. When the shuttle reached the end of its travel, the aircraft and bridle (sometimes called a “strop”) continued on and parted ways. The bridle was sent flying overboard and was considered expendable. One can imagine the world’s ocean floors littered with hundreds of thousands of these heavy cable strops. Below the aircraft we see two angled rails (known as guide cleats) bolted to the deck for launch, which helped guide the aircraft to the exact centred position over the shuttle rail. In the summer of 1945, 896 Squadron embarked on Empress and worked with the 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron. Photo via Pinterest

Empress suffered engine damage during DUKEDOM and returned to Trinco on 22 May and was fit for service before the end of the month. She would spend all of June working up various squadrons, then in July participated briefly and in some non-aviation support role in Operation COLLIE, the continued attacks and bombardments of Japanese installations on the Nicobar Islands group. On 19 July, she participated along with Ameer and the ships of Force 63 in Operation LIVERY, a British naval undertaking to clear mines from the waters round Phuket Island off the west coast of Japanese-occupied Thailand and to make air attacks on Japanese airfields on the Kra Isthmus. The flotilla came under kamikaze attack, and during the operation one Hellcat was lost for the score of 30 Japanese aircraft (including kamikazes). This would be the last offensive operation conducted by the British East Indies Fleet.

Outward bound across the Indian Ocean from Trincomalee, Ceylon to attack enemy targets in Malaya as part of Operation LIVERY, Captain J.R.S. Brown, RN, Empress’ commander, explains the operation to his ship’s company with the aid of a chalked map under the island structure on the flight deck. Writers from the Royal Navy Research Archive explain: “Empress was deployed with Force 63 for Operation LIVERY on 19 July; the force comprised of battleship Nelson, cruiser Sussex, and CVEs Empress and Ameer with destroyers Paladin, Rotherham, Racehorse and Raider to cover minesweeping operations… and conduct strikes on targets in northern Malaya. The operation began on the 24th and was to last for three days. This was an intense flying period for the two CVEs, over a 3-day period. Hellcats from both carriers flew over 150 sorties and destroyed more than 30 Japanese aircraft on the ground, together with trains and road transport in attacks on Kra Isthmus. On 26 July, HMS Ameer was attacked by a kamikaze; a single “Sonia” [Mitsubishi Ki-51] attempted to dive onto Ameer, it was hit and successfully deflected by fire from the ship’s defensive armament, splashing into the sea some 500 yards out.” Photo: Imperial War Museum

She would join other Royal Navy elements for Operation CARSON to attack Penang and Medan in Malaya, but the war ended and they were withdrawn. In September of 1945, Empress joined Ameer, Emperor, Hunter, Khedive and Stalker in Operation ZIPPER, the military re-occupation/ liberation of Singapore. She was one of 90 Allied ships anchored in the Singapore Roads for the surrender. Following this she returned to Trincomalee.

Empress was used to return servicemen and women from Colombo to Australia and New Zealand in October and November, then she left for the United Kingdom, dropping anchor in the Clyde on 19 December. After de-storing and the removal of Royal Navy equipment, she sailed to Norfolk with a skeleton crew, arriving on 20 January 1946. By the summer she had been sold for scrap.

Norma Tulee, a young Walthamstow actress touring units and ships of the Southeast Asian Command with the ENSA show ‘Variety Express’, made a great hit with Empress’ company at Colombo, Ceylon. Sailors and possibly a pilot (right) enjoy chalking her name on a Seafire. One sailor in the gob hat at the back seems interested in more than the chalk. ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association) was an organization set up in 1939 to provide entertainment for British servicemen and women during the Second World War. While ENSA’s list of luminaries included Terry Thomas, Josephine Baker, Gracie Fields, Noël Coward, John Gielgud, Stewart Granger, Jack Hawkins, Vivian Leigh, Vera Lynn, Spike Milligan and Alastair Sim, I could not find a single reference to a woman named Norma Tulee anywhere on the web. Photo: Imperial War Museum

How wonderful would it have been to be aboard one of His Majesty’s Ships in Trincomalee harbour when news that the Japanese had surrendered was received? The night sky is alive and aflame with flares and star shells, and no doubt the ships’ horns are blasting away while the men cheer from every rail. The elation of knowing that they had survived the war and did not have to fight the Japanese on their home islands must have been euphoric for the sailors. VJ-Day is a term that refers to the day that the Japanese signed the “instruments of surrender” aboard the battleship USS Missouri (2 September 1945), but it is also used to define the day that the Japanese initially surrendered and stopped fighting (15 August 1945). This particular photograph, taken from the deck of HMS Empress in Trincomalee harbour, was shot on the latter day. Empress was in Trincomalee until 15 August, getting ready to sail to support a planned British landing (Operation ZIPPER) on the Malayan Peninsula. Despite the news of the surrender, Empress and her task force sailed for Penang in Malaya, where she was when the Japanese signed the surrender documents in Tokyo Harbour. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A terrific shot of HMS Empress at Wellington, New Zealand in November of 1945 with a large turnout of her crew and perhaps passengers being brought home at the port edge of the flight deck. From here, she sailed back to Colombo and thence to the Clyde in December. In January, she sailed for Norfolk, Virginia and was handed over to the United States Navy. Photo: histarmar.com.ar

HMS Khedive (Pennant Number D62)

The caption accompanying this photo of HMS Khedive in the Imperial War Museum archive simply states “Underway, coastal waters”, but the sloping land form in the distance tells us that this was on the Clyde near Greenock, Scotland. Photo: Imperial War Museum