TWO WINGS & TOO LATE — THE GREGOR FDB-1

There is no doubt that Canada, pound for pound, fights above its weight when it comes to aerospace technology and contribution to modern aircraft design and propulsion systems. Canadians have always put their talents and genius behind aerospace projects that effect their daily lives–simple aircraft that perform rugged tasks, hauling freight and Canadians across vast areas, connecting communities, making all corners of Canada accessible. From our love affair with the de Havilland Beaver and its simple workman-like beauty to the slender high tech simplicity of the Dash-8/Q400 series of airliners found all over the modern world to the ubiquity of the PWC PT-6 series turboprop engines, Canada's mark on modern aviation is huge, and quietly, humbly, everywhere from Alert to Antarctica to Europe to the Equator.

Our engine and aircraft designers are second to none. Our efforts are largely focused on solving aerospace problems that make life easier in a country where cities are strung out across the bottom of the land like a necklace, but our aerospace technology benefits the entire world. Medical evacuations from the South Pole in the dead of winter are possible with Canadian pilots (Kenn Borek), Canadian aircraft (Twin Otter) and Canadian engines (PWC PT6). From Scandinavia to Japan to New York to Sydney, passengers enjoy the comfort and quiet of Dash-8 and Q400 medium range airliners. Business executives and rock stars travel in luxury aboard Canadair Challenger business jets. Canada is an aerospace giant… albeit a quiet one.

Our vast and peaceable country is not today and never will be a centre for designers, builders and purveyors of front line offensive aircraft like fighters and bombers. But that doesn't mean we didn't give it a try. While Canadians, through licence, have built thousands upon thousands of offensive aircraft, from Hurricanes, Lancasters and Mosquitos to Sabres and Starfighters, the successful home grown fighter aircraft design has eluded us entirely except for the Avro CF-100 Canuck, a large straight-winged all weather interceptor of the 1950s. Its utility was unquestionable, its capabilities solid, reliable and workman-like, but it failed to capture the imagination like the spiffy delta-winged and needle nosed fighters of the United Sates, France and Great Britain. Even its nicknames gave vent to its lack of glamour – the Clunk, the Lead Sled, the Zilch or the Beast. It was so solidly built that, though the airframes were designed for 2,000 hours, they could last for more than 20,000 hours.

The Avro CF-100 Canuck looked pretty respectable straight on and lived up to its billing as a steady, reliable all-weather interceptor. Of the nearly 700 “Clunks” built, 53 were exported to the Belgian Air Force, making the CF-100 the only Canadian designed fighter aircraft ever to be exported and flown by foreign air arm. Photo: RCAF

The one other home grown attempt to get into the Cold War fighter game, the Avro CF-105 Arrow was everything the CF-100 was not–sexy, rocket-fast, expensive, glamourous, sleek, lean, gigantic and so not like us Canadians. By any standards of design today, it was a visual stunner. It held the promise on its broad white wings that Canada would be vaulted into the future ahead of everyone. It held the promise of Mach 3 and ceilings of 60,000 feet. It was in the prototype and test stages of its development when the entire project was cancelled in 1958 due to runaway cost overruns, strategic realignment and, as some conspiracy theorists like to say, meddling from big business and government south of the 49th parallel. It was all a bunch of hoohaw. The development of the Arrow was simply too expensive for a country of a 16 million (1956) sober souls to shoulder. Americans already had in place aircraft with similar capabilities. The bleeding had to stop.

The Avro CF-105 Arrow was the “Camelot” of Canadian aircraft design. I can hear Richard Burton intoning "Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a dream, for one brief, shining moment, that was known as Arrow". In a spasm of federal vandalism, the Conservative government of the day had all 6 flyable copies cut to pieces and scrapped. It was hoped that the Arrow could and would do many things. In the end it was most successful at spawning controversy, whacko mythologies, and the strange nonsensical idea that it was so good that it would be the world's only fighter aircraft still in production 60 years after its first flight. Photo: Avro Canada

The Arrow–she was big and beautiful, and for Canadians wanting to get into the fighter business, one big all-or-nothing try. Aviation basement dwellers still spend countless hours lamenting its loss or searching for a survivor in Ontario barns or ballistic test models at the bottom of Lake Ontario. They photoshop squadrons of them in modern RCAF markings streaking to the defence of the nation some 60 years after the first flight, and obsess about a dream that could never have been instead of dreaming about things that lie ahead. Thankfully, the Canadian aerospace industry got up, dusted itself off and got down to the business of being an aviation powerhouse. Photo: Avro Canada

With the demise of the Arrow, the Canadian home-grown fighter idea died… thankfully. Now Canadians could build licensed Starfighters and Sabres, and focus their design attentions on what would eventually lead them to become one of the greatest aerospace countries in the world. Meanwhile, over the next five decades the fighter business dwindled and shrunk in Britain and the US. Gone today are the fighter giants of years gone by – Supermarine, Hawker, de Havilland, English Electric, Blackburn, Republic, North American, Convair, Douglas, Northrop, Vought, McDonnell and many more. Today, after mergers and devourings, only a few blended players remain standing. Canada should be grateful for the cancellation of the Arrow, as its demise enabled our manufacturers to focus on where the money and future was–civil aviation.

Related Stories

Click on image

The Other Canadian Fighter Aircraft Failure

There is one other fighter aircraft, designed and built in Canada that most Canadians, even aerophiles, know little about. It too was beautiful and elegant, with lots of promise, considered by some to be the finest of its type built to that point. The problem was that the type was the high-performance biplane fighter-bomber. The aircraft was the Gregor FDB-1 (FDB for Fighter/Dive Bomber), designed and built at Canadian Car and Foundry (Can-Car) in Fort William, Ontario. Sadly, biplane fighters at the time of the FDB-1's first flight in February, 1939, were about as out of favour as dirigibles, observation balloons, and tri-planes.

While there were plenty of biplane fighters in operation around the world at the time, and a couple (Polikarpov Chaika and the Fiat Falco) that were just coming on line at the time of the Gregor, they were the final variants in a largely successful line of biplane fighters, stretching back a decade, recognized for the good qualities, and made better as an interim solution before the arrival of the new generation of all-metal monoplane fighter aircraft. Consider that the Hurricane, Spitfire, P-40 Warhawk, and Messerschmitt Bf-109 were all operational by the time of the Gregor's first flight. Within one calendar year after the first flight of the Gregor fighter, the Vought Corsair, P-38 Lightning, Mitsubishi Zero and FW-190 would make their maiden flights.

Though much of the design and all of the construction of the FDB-1 prototype took place in Fort Willam's Canadian Car and Foundry Factory out on the far reaches of the Great Lakes, it was in fact not designed by a Canadian. But if the American's can claim that the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs were 100% American and ignore the impact of the more than 40 German rocketeers like Werner von Braun, then the Gregor FDB-1 was a Canadian as Howie Morenz.

The lead designer on the FDB-1 project at Can-Car and the man after whom it would be named, was a Georgian by the name of Mikhail Leontyevich Grigorashvili who had come to Canada as an American citizen, failed entrepreneur and now newly-hired Chief Designer. By the time he arrived at Fort William (today's Thunder Bay), he was known simply as Michael Gregor, aircraft designer and the owner of an impressive resumé with experience both in the Soviet Union and in the United States of America.

Grigorashvili was part the Russian (from Georgia, predominantly) invasion of exceptional aircraft designers that were the lucky fallout for the United States of America–men like Igor Sikorsky, Alexander de Seversky, Alexander Kartvelishvili, Mikhail Grigorashvili and Mikhail Stroukoff. When the Bolsheviks took over Russia from the aristocrats, nobles and Tsars in 1917, it was only a matter of time before they laid the same iron hand on neighbouring states and created the Soviet Union. There was no love lost between the communists who rose from the factory worker and peasant classes and the intellectual and refined noble classes of Russia and the new Soviet states like Georgia and the Ukraine. Facing steady marginalization and inevitable death as aristocrats in an intellectual pogrom, these future talented designers and latent capitalists headed for fertile territory.

Russian émigré aircraft designer Mikhail Leontyevich Grigorashvili, known in Canada and the United States simply as Michael Gregor was a Georgian-born, Russian aviator and aircraft designer from Derbent on the Caspian Sea. He was well known in Russian aviation circles at the beginning of flight in that country and we see him here (second from right in the back row) with a group of Russian participants and organizers of the first flight from St. Petersburg to Moscow, July 1911. Inset: Grigorashvili in the cockpit of his Blériot XI, which he did extensive modifications on. In fact, he built this particular aircraft for a Russian nobleman by the name of de Seversky, one of the first two aviators in Russia. I checked with a Russian friend and the text on the side of his Blériot simply states “Aviator Grigorashvili” in the traditional old Imperial Russian script. It would be de Seversky's son, Alexander who would create the massive American company we know today as Republic Aircraft. Grigosashvili was one of several exceptional Russian aircraft designers, including Alexander de Seversky, Igor Sikorsky, and Alexander Kartveli (Kartvellishvili) who left communist Russia and found not just employment but great aerospace business success in Canada and the United States. Photos via linkgeorgia.com

Igor Sikorsky is considered the father of the modern rotor winged aircraft configuration. In Russia he designed and flew the world's first multi-engine aircraft, the Russky Vityaz in 1913 and later in 1914, the worlds first airliner–the Ilya Muromets. He was born in Kiev, Ukraine to a father with both Russian and Polish nobility in his blood. His company is one of the largest helicopter aerospace companies in the US today.

Alexander de Seversky was also born a noble in Tblisi, Georgia, part of the Russian Empire. His father was one of the first Russian aviators, whose first aircraft was a Blériot custom modified by Mikhail Grigorashvili. A decorated naval aviator of the First World War, he was a Russian naval attaché to the United Sates in 1917. Following the revolution, he remained in the United Sates. With money made from patents for the world's first gyro-stabilized bomb sight and a patent for air-to-air refueling, he started Seversky Aero Corporation, which would move and grow over the years and become the aerospace behemoth known as Republic Aviation Corporation, producers of the P-47 Thunderbolt, Seabee, F-105 Thunderchief and the F-84 series fighters - ThunderJet, ThunderFlash and ThunderStreak.

Alexander Kartvelishvili was another Georgian ex-patriot with nobility in his blood. Following the turmoil of the revolution, he moved to France where he graduated from the Highest School of Aviation in Paris. After moving to the US, and with an abbreviated name, Alex Kartveli became an influential aircraft engineer and a pioneer in American aviation history. He led the team (with Mikhael Gregor) that designed and produced the robust P-47 Thunderbolt, the largest, heaviest, and most expensive fighter aircraft in history to be powered by a single piston engine. Kartveli achieved important breakthroughs in military aviation in the time of turbojet fighters. He is considered to be one of the most important and innovative aircraft designers in US history and the world.

The Mount Rushmore of aircraft designers who were born in the former Russian Empire. Left to right: Igor Sikorsky (Kiev, Ukraiine), Alexander Kartvelishvili (Tbilisi, Georgia) and Alexander de Seversky (Tbilisi, Georgia). They built aerospace companies worth billions. Images via Internet

Michaal Gregor, the man who would lead the design of the FDB-1, certainly the last of the new-concept biplane gun fighters was part of this Russian pantheon. At the time, there is no doubt that the Can-Car design team had not fully thought out the wisdom of another, albeit sophisticated, biplane fighter aircraft when the first flights of the Messerschmitt Bf-109 and Spitfire had happened years before. They surely thought, as do many companies today that hang onto legacy technologies, that there will always be a task for a biplane fighter. And Canadian Car and Foundry, learning that Gregor was of the same background as de Seversky and Kartveli, the emerging superstars of modern fighter development in the United States, could not help but bring him into the fold as a designer/saviour that would elevate them from license-building copies of other company's aircraft to building legends.

Gregor, one of several accomplished Russian aircraft designers to immigrate to the United States from Russia, designed three aircraft types with his name on them. Photo via nplg.gov.ge

A Georgian by birth, Mikhail Grigorashvili was not happy with the communist takeover of Russia at the end of the First World War. He moved home to the Republic of Georgia in early 1918. But in 1921, facing a Russian occupation of Georgia, Grigorashvili was forced to move again, this time to the United States, working as an engineer and designer for a number of aircraft manufacturing companies including Curtiss-Wright as a senior designer. In 1926, he became a US citizen and then in 1928, he became Chief Designer at the Bird Aircraft Company (formerly Brunner-Winkle) of Glendale, New York. There, he was instrumental in the creation of a fairly successful and much loved aircraft called the Brunner-Winkle Bird, a three seat taxi and joy-riding aircraft. The Brunner-Winkle Bird had some innovative features that made it unique among its peers. It had a particularly thick upper wing which gave it a higher lift and made for easy control at lower speeds and a radiator under the fuselage. Photo via Wikipedia.

The Brunner-Winkle Bird, designed by Michael Gregor (an American citizen by this time) was a lovely little aircraft in many respects. The Model A (seen here) was powered by the Curtiss OX-5 in-line engine. The Model A's ease of handling led to its entry into the 1929 Guggenheim Safety Airplane contest, where it was awarded the highest ratings for a standard production aircraft. The model B was powered by the more reliable Kinner K-5 un-cowled radial. Note the Bird winged logo on fuselage. Photo via San Diego Air and Space Museum Flicker page.

The Brunner-Winkle Bird was considered one of the safest aircraft to fly at the time and so Charles Lindbergh purchased a Kinner radial-powered Model B for his wife Anne Morrow to complete her flying lessons. This would have been a considerable compliment to the design of the young Gregor. Note the Bird logo on the fuselage. Photo via Lindbergh Picture Collection Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University

Between 230 and 240 Brunner-Winkle Birds were manufactured before the company folded. Though the company did not live long, the Bird was considered by all who flew it to be an excellent airplane, the finest ever powered by a Curtiss OX-5 engine. Of the 220 plus aircraft built, nearly 70 exist today–a testament to Michael Gregor's exceptional and solid design. Photo via Cradle of Aviation Museum

After a four year stint as Chief Designer at The Bird Aircraft Company on Long Island, Gregor then worked as Deputy chief designer at Seversky Aircraft Corporation which was located at Roosevelt Field, also on Long Island at the small community of Mineola. After his time at Seversky (the future Republic Aircraft), Gregor started up his own aircraft design company–the Gregor Aircraft Corporation. As President and Chief Designer, he designed and built two biplane aircraft–the GR-1 and the GR-2. In this photo, Michael Gregor's Gregor GR-1 biplane is parked outside the Gregor Aircraft hangar (Hangar B-note letter B at upper left) on the main hangar line at Roosevelt. Roosevelt, seemed to attract the very best of Russian aircraft designers including Gregor and Alex Kartveli at Seversky, and Igor Sikorsky. It was from Roosevelt that Charles Lindbergh took off on his successful attempt in the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927.

Gregor Aircraft Corporation's home field. An undated aerial view of the main hangar line of Roosevelt Field–looking west along the northern row of hangars at Roosevelt Field. The photo is presumably from late in the life of Roosevelt Field (late 1940s / early 1950s?), as the eastern-most hangar (Hangar A) had already been removed. The Gregor Aircraft Corporation hangar (Hangar B) is the one still standing at right. Photo via http://www.airfields-freeman.com

The Gregor GR-1, also called the GR-1 Continental and the GR-1 Sportplane, was a biplane with a tail-wheel undercarriage and was intended to be a light, low cost, training aircraft for depression-era customers. Gregor was based at Hangar B at Roosevelt Field in New York. As there was only on GR-1 aircraft built, this is the one seen parked at the Gregor Hangar at Roosevelt Field in a previous photo. While at Gregor Aircraft Corporation, Gregor received US patent #1,747,001 in 1930 for a cockpit-controlled wing-tip aileron device to help overcome stalling, but there is no record of this ever showing up on any wing-tips. Photo via Frank Rezich Collection at Aeroiles.com

A Gregor GR-1 at Roosevelt Field with two pretty airwomen providing some much needed marketing power. While the Bird biplane designed for Brunner Winkle was a relative success, his own Gregor GR-1 was a one-off. Gregor also developed another similar biplane called the GR-2, but no photographs were found on the web. Gregor at this time had eliminated much of the traditional biplane wire bracing with use of a large interplane strut. On the FDB-1, Gregor would employ a similarly robust interplane device combined with two other struts and eliminate the use of wire braces completely. Photo via the Long Island Early Fliers Club.

Gregor had a pretty impressive resumé, having worked in aircraft design at Dayton-Wright Aircraft, Curtiss-Wright, Bird Aircraft and had been the Deputy Chief Designer at Seversky's growing company, working with him on early design development on aircraft that would ultimately lead to the P-47 Thunderbolt. In 1937, Gregor was hired by Canadian Car and Foundry as Chief Designer, working on in-house projects and beginning the process of designing and building a new biplane fighter-bomber of his own design. The rest of the world, including the RAF which the RCAF would likely follow was either converting to the monoplane or deploying the the last variants of biplanes that had been in development and use for years. Despite the fact that there were some who doubted the attributes of a monoplane as a better configuration than the reliable old biplane, history would, in a matter of months, demonstrate the ascendancy and indeed supremacy of the all-metal monoplane fighter and bomber.

The Finale – The Canadian Car and Foundry Gregor FDB-1

In many respects, the Gregor FDB-1 would be Michael Gregor's and indeed the likely the world's last brand new ground-up biplane fighter design–his finale. In describing the attributes and technological details of the FDB-1, I think I could not do as well as the Wikipedia entry for the Gregor. It lays out plenty of detail:

Similar in size and dimensions to Grumman's F2F Navy fighter and also designed to operate from aircraft carriers as a dual fighter/bomber, Michael Gregor's FDB-1 had an empty weight of 2,880 lb and a gross of 4,100 lb. As in many other gull wing fighters, pilot's view while flying straight and level was excellent, but marginal when landing and extremely poor when looking downward during that critical phase. Hydraulically operated landing gear retracted flush into large wells on either side of fuselage, ahead of the lower wing. Twenty-eight foot span top wing featured nearly full span slats measuring 10 ft (3 m) per side, plus all-metal split flaps of 4 ft (1 m), 3 in per side, positioned between root and ailerons. Bottom wing span of 23 ft (7 m), 10 in also incorporated longer split flaps of 7 ft (2 m), 9 in per side. Like many a Soviet and Polish contemporary that had preceded it, biplanes as well as high-wing monoplanes – the center section of the top wing on Gregor's trim fighter had a gull-wing configuration, attached at right angles to the fuselage for less drag. This was supposed to afford improved visibility too, particularly straight ahead in level flight.

Michael Gregor's greatest design triumph was most certainly his elegant, fast and a little too late FDB-1 Gregor fighter/dive bomber. Here we see executives from Canadian Car and Foundry on a clear and cold winter's day at Bishop's Field Fort William (Thunder Bay) at the time of the foist engine run ups. Here, test pilot George Adye (Left), Canadian car and Foundry representative David Boyd (the Fort William Factory Manager) and supposedly 50-year old aircraft designer Michael Gregor (right) pose with the gorgeous little fighter, painted in all over semi-gloss grey.

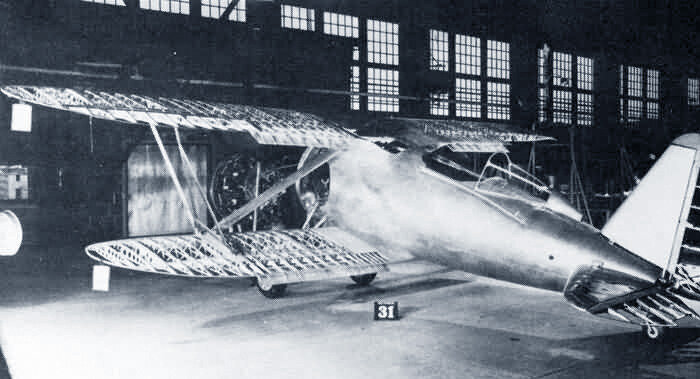

The best qualities of the Gregor FDB-1 can be seen in this shot in the Canadian Car and Foundry factory at Fort William –the all-metal construction, the retractable undercarriage, flush riveting and gull wing shape of the upper wing. For a biplane, the Gregor was exceptionally sleek, yet robust. It had a modern monocoque shell construction similar to the finest monoplane aircraft of the day such as the Spitfire and the Messerschmitt Bf-109. Even the Hawker Hurricane, a monoplane fighter, which would shoulder the bulk of the sorties in the Battle of Britain two years later, had a much less sophisticated steel tube construction. Photo via deadlybirds.com.br

Assembly of the all-metal wings for the FDB-1. Photo: Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society

Another shot of the FDB-1 under construction at Fort William with her beautiful wings attached. Likely they wold have been removed in order to be skinned. The FDB-1 was an all metal biplane, but it appears that the wings would have been skinned in fabric. Photo from Johan Visschedijk Collection via 1000aircraftphotos.com

The compact 21 ft (6 m), 8 in fuselage of the Model 10 FDB-I utilized a monocoque shell of circular cross section, covered by flush-riveted, stressed skin. The all-metal wings were fabric covered behind the front spar and metal-framed control surfaces were also fabric covered. An anticipated range of 985 miles (1,585 km) was based on 95 gallons of fuel carried in a pair of semicircular-shaped tanks mounted side-by-side in the fuselage, between the wheel wells. The structure was extremely robust and capable of withstanding stress forces 60 percent above requirements. A pair of fuselage-mounted .50 cal. machine guns, synchronized to fire through the Hamilton Standard's nine ft propeller arc, were part of the design, but armament was never installed. Additionally, two 116 lb bombs were to have been carried, one under each lower wing.[1]

Streamlining on the FDB-1 was accentuated. The engine was snugly faired into a NACA cowling reminiscent of earlier Seversky fighter designs, also heavily influenced by Gregor, who left that company early in 1937. The rearward sliding center section of cockpit's canopy, spacious for such a small airframe, was a unique Gregor innovation. The FDB-1 clean lines partly were accomplished by the attachment and support of wings via substantial faired "V" interlane struts. Flying and landing wires and cables were replaced by a single faired strut running between the root of the top wing rear spar and the foot of the "V" strut where it joins the lower wing at its front spar. A system of tubes moved the control surfaces, except for the rudder, which was partially operated by cables.

The only Canadian Car and Foundry-built Gregor FDB-1 is rolled out of the Fort William factory on a cold and clear December day in 1938 for a photo op and engine run. The aircraft is not yet been fitted with its massive bare metal spinner of the final design. Photo from Johan Visschedijk Collection via 1000aircraftphotos.com

The roll-out with Gregor at right in Homburg and coat. Photo: Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society

George Adye about to start the FDB-1 for the first time at the roll-out on December 17th, 1948 at Bishop's Field, Fort William. Adye was the Canadian Car and Foundry factory pilot. On this December day he would just run up the engine, but he would be the first to fly the Gregor FDB-1 at Can.Car's factory in St. Hubert near Montreal in February, 1939.

George Adye, Canada Car and Foundry test pilot, appearing to still be wearing the jacket and tie from the group photo above, sits in the roomy cockpit of the FDB-1 getting ready to turn over the engine. The cockpit and the control ergonomics were designed around the six foot Adye, and proved to be difficult to use for shorter pilots who flew it — like Victor “Shorty” Hatton, a pilot and sales executive with Canadian Car and Foundry.

The huge perspex canopy of the FDB-1 is clearly shown in this image from the December 1938 roll-out. The canopy gave a tremendous field of vision in all directions... save forward where the high mounted gull-style wing impeded view. Photo via airwar.ru

The flat distortion of the pilot's face in this shot leads me to believe that this is a photograph of a photograph of the FDB-1 in flight. The internet does not have any in-flight shots of the Gregor other than this. If anyone has images of this beauty in flight, please send them along. Photo via fliegerweb.com

Another better shot of the FDB-1 in flight. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

I am not sure who was the original artist of this correctly painted aircraft profile which can be found on the Russian website called Wings Palette. They were not able to attribute credit, but if someone knows, let me know. It carries the FDB-1 title on the tail, which was applied after the original roll out photos were taken.

When rolled out, the Gregor FDB-1, as it was called, for Fighter Dive Bomber, was not only robust and solid, it also looked exceptionally sleek. Registered CF-BMB, the letters embossed in white over a high gloss metallic dark gray paint job, the dual purpose aircraft's only other markings were ten horizontal white bands on its rudder.

Early in 1938, in a spirit of Commonwealth cooperation, a wooden model of Gregor's new Model 10 fighter was sent to Hawker Aircraft's wind tunnel facility at Kingston upon Thames, England. Manufacture of the prototype began at Thunder Bay, on the north shore of Lake Superior, shortly thereafter. The aircraft, c/n 201, was completed by mid-December 1938, "amid an atmosphere of war jitters, well salted with tales of German spies visiting the factory in disguise."

On its first flight test on 17 December 1938 Can-Car Test pilot George Adye put the FDB-1 through a preliminary flight test program carried out at Can-Car's Bishopfield Airport, Thunder Bay, on Lake Superior. [Author Jonathan Kirton, an historian who wrote a book on the subject of Can-Car, has since determined that the first test flights of the FDB-1 were undertaken at Montreal and not at Thunderbay as indicated here in the Wikipedia entry. We can assume that the test pilot Adye's findings are correct.–Ed] Ayde immediately noted the upper gull wing was a major defect as on takeoff and landing, a pilot's vision was severely limited downward and forward. Ted Smith who tested the FDB-1 in 1941 was more succinct when describing visibility over the gull wing, "blind as hell."

While expressing enthusiasm over its maneuverability, Ayde warned that the controls were far too sensitive and the angles of the lowered flaps too great. His assessment was correct; on a subsequent landing, the prototype flipped on its back, although the damage was kept to a minimum due to its rugged construction.

Among the new devices incorporated within the FDB-1 was an anti-spin parachute in its tail cone. The pilot activated the parachute from the cockpit by a three-position switch. The first opened the cone, the second deployed the chute behind the aircraft, and the third released the connecting cable.

Recorded top speed was only 261 mph (420 km/h) at 13,100 ft (3,990 m), with the old P&W R-1535-72 engine of 700 hp, which had powered the Grumman F2F-1. But that aircraft, with a slightly lower empty weight, had only reached a top speed of 230 mph (370 km/h). With the installation of an improved P&W R-1535-SB4-G of 750 hp, top speed was expected to rise to 300 mph (500 km/h). Meanwhile, Gregor had already programmed his fighter to accept the 1200 hp. P&W R-1830 Twin Wasp then being installed in Grumman's new monoplane fighter, the XF4F-3; and with it, he fully anticipated a top speed of 365 mph (587 km/h). and aircraft was highly maneuverable. Initial rate of climb was an exceptional 3,500 ft (1,070 m). per min, compared to Grumman F2F's 2,050 ft (625 m) per min. with same engine. Service ceiling was estimated at 32,000 ft (9,800 m), 5,000 ft (1,520 m) higher than the F2F's. FDB-1 had a cruise of 205 mph (330 km/h), a low-speed capability of 72 mph (116 km/h) clean and, with flaps and slats open, 58 mph (93 km/h). All these figures were reached without armament, ammunition, armor plate and other military equipment including self-sealing fuel tanks.

Designed, built and tested in less than eight months, the FDB-1 Model 10 was sent to Saint-Hubert Air Base, near Montreal, for preliminary service testing with the Royal Canadian Air Force. After extensive trials, pilot evaluations complained of severe canopy vibration at speed and during strenuous aerobatics, and it was recommended hat all testing be restricted until this bothersome defect had been remedied. Unfortunately for Gregor and Can-Car, further tests undertaken by the RCAF showed that his first projections were extremely optimistic and doubted further refinements would make a difference. Nevertheless, the FDB-1 did demonstrate amazing maneuverability; below 15,000 ft (4,600 m), in spite of an adversary's superior speed, no contemporary single-seat, low-wing monoplane could successfully engage Gregor's design which climbed like a "homesick angel," with an initial rate of 3,500 ft (1,070 m) per min, one third better than the new Hurricane and Spitfire. Test pilot Ted Smith thought that the FDB-1 was intended for "mountain" fighting once he sampled its phenomenal climbing ability. – Wikipedia

RCAF Flight Lieutenant L.E. Wray made a test hop on May 10. Apart from an alarming canopy vibration during loops, he was taken by its snappy handling. Performance, not so much. Wray recorded an initial climb rate of 2,800 feet per minute (Can-Car had predicted 3,400) and 402 mph in the dive (against Can-Car’s 472 mph), with an easy 7-G pullout. The gull-wing blinded him on landing, but “it has maneuverability to the extreme,” he wrote. “Below 15,000 feet, a contemporary low-wing monoplane or single seater, despite superior performance, could not successfully engage the Gregor singly.”

Not sure where this image was taken.

In the background, two well-dressed men approach the beautiful Gregor FDB-1 sitting at the edge of the hardstand outside a Roosevelt Field, Long Island hangar. The FDB-1 now carries her FDB-1 title on her tail. A Gulf Oil fuel bowser can just be seen forward of the starboard wings and the attendant standing on a step ladder to assist the refuelling. Canadian Car and Foundry had the aircraft flown down to Gregor's old airfield for evaluation and to drum up interest in the hot little biplane. The problem was that is was a biplane, and the aviation world was now enamoured of the sleek monoplane fighters like the spitfire whose first flight happened two years before that of the FDB-1. Gregor, upset that no one was interested in his biplane, had apparently quipped "They'll start this war with monoplanes, but they'll finish it with biplanes." Clearly his prediction was as far from the facts as one could imagine. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

A photo possibly take at roosevelt Field.

A great photo showing a Gulf Oil fuel truck attendant assisting the FDB-1 pilot while the dapper man in the light coloured fedora from the previous photos gets a closer look at the little warplane. Photo via deadlybirds.com.br

A great shot of the Gregor FDB-1, taken at the Roosevelt Field. The factory test pilot's parachute sits on the port wing. The massive three bladed propeller and huge nose spinner gave the FDB-1 a formidable appearance on the ground. The propeller would likely have been an important component for designer Gregor. During the First World War, from 1915 to 1917, Gregor (Grigorashvili) worked as the chief designer at the aviation factory of R.F. Meltzer where managed design, testing and production of propellers of his own design. At the time, he and the Meltzer company were leaders in Russian propeller construction and manufacturing. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

Aviation executives take a close look at the FDB-1 at Roosevelt field in 1938. Photo via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

The Gregor FDB-1 during the sales tour in the US

Gregor's use of all metal fuselage and flush riveting give the Gregor a look of a modern monoplane fighter with the addition of an upper wing. No one will ever know how the aircraft would have performed with the weight of machine guns, ammunition and bombs, as it failed to interest a monoplane world.

Canada, though an aviation giant today in medium range airliners, business jets and aircraft engines, has never been a recognize producer of indigenous military fighter aircraft. Though the FDB-1 was in fact the brainchild of an Georgian-born, American citizen, it was embraced as Canada's first fighter. Sadly, like the Avro Arrow some twenty years later, it was a failure for reason's beyond it capabilities. Canada's only successful indigenous fighter aircraft design was the big all weather interceptor known as the Cf-100 Canuck. Here we see some popular culture cards from the day featuring the little “Canadian” biplane fighter. Upper left: An ink blotter give-away with purchase from the Canadian gas/service station chain called Supertest. These were given away at gas stations to customers as one of the many complimentary services they offered. Upper right: a “cigarette card” from the Second World War features a depiction of the FDB-1 in flight, but with a spurious blue white and red paint scheme. The FDB-1 was grey over all, with all other markings in white. Perhaps because it looked similar to black and white photographs of American aircraft with dark blue paint and horizontal red and white stripes on the tail, it was depicted thus and this would remain for decades as the paint scheme it wore, despite being wrong. Bottom: Another spurious image shows the FDB-1 obviously sitting on the snow at Fort William, but now with an RCAF/RAF A-type roundel, which she never wore. The Second World War "Aviation Chewing Gum" card set was issued by World Wide Gum, the Canadian subsidiary the Goudey Gum Company, and featured 210 Allied aircraft. As well, this chewing gum card indicates that the FDB-1 was powered by a 200 HP Maple Leaf engine and was built in Montreal. In fact, the only one built was from Fort William and it was powered by a 700 HP Pratt and Whitney R-1535 engine. Images via the internet

Overview production drawing from CCF

A mahogany desktop model of the Gregor FDB-1 shows us its most outstanding angle, high on the front quarter with its beautiful gull wings looking oh-so-pretty... and blocking oh-so-much of the pilot's view forward to the left and right. As a private high performance two-seater, it would have been magnificent. Photo via Lloyd Ralston Gelleries

I found a photo of a lovely model of the Gregor FDB-1 which shows a colour close to the correct grey colour, but with red and white rudder stripes. Photo and model by Alexandre Bigey

In a last-ditch effort to generate some interest in its new fighter, Can-Car entered the Model 10 in the January 1940 New York-to-Miami air race. Shortly after takeoff, a lack of oil pressure forced the FDB-1 to land in New Jersey, thereby disqualifying it. Two months later, during testing, its landing gear collapsed at Saint-Hubert. Although Mexican authorities were interested in the aircraft, the Canadian government refused an export license and there were no other prospective customers for a biplane fighter in an age of monoplanes.

In a fit of pique, Gregor was quoted as saying: "They'll start this war with monoplanes, but they'll finish it with biplanes." He was wrong. Neither his prediction nor his aircraft were to survive the test of time. After several years of sitting forlornly in storage, the Model 10 FDB-1 was destroyed in a hangar fire at Montreal's Cartierville Airport, and Michael Gregor swiftly followed it into obscurity. – Wikipedia

Gregor–after the FDB-1 Disappointment

After Gregor left Canadian Car and Foundry, he was employed from 1944 to 1953 as Chief Designer at a brand new aerospace company called Chase Aircraft Corporation out of Trenton, New Jersey. In the book “Rearming the Cold War” by Elliot V. Converse III, Stroukoff, the founder of the company is referred to as “Mike, the “Mad Russian” Stroukoff, the company's colorful founder.” Gregor and Stroukoff were responsible for the design development of the C-123 Provider, one of the the early post-war medium lift transports employed by the United States Air Force, Without a doubt, the Provider would have vaulted Gregor and Stroukoff into the pantheon of Russian emigré aircraft designer legends of the US, except a procurement scandal resulted in the building of the subsequent 307 Provider airframes being handed to Fairchild. By 1953, the majority of shares in Chase had been purchased by automotive magnate Henry Kaiser, and he was embroiled in a pricing scandal which led the contract being awarded to Fairchild Engine and Airplane, who assumed production of the former Chase C-123B, a refined version of the XC-123.Before turning production over to Fairchild, Chase originally named their C-123B the AVITRUC but it never stuck. Poor Gregor was that close to being part of a huge success, but never got there. He died in 1953,

As the Chase Aircraft Corporation was being dissolved as a useless asset of Kaiser's. Stroukoff would then buy the assets of Chase and open Stroukoff Aircraft Corporation. He stumbled along for another 6 years, experimenting wiht the C-123 modifying one as the fist jet tranmsport in US history and another a C-123B into the YC-123E, fitted with Stroukoff's own Pantobase landing gear system. The Pantobase system (essentially a large extendable skid) allowed the aircraft to land on any reasonably flat surface - land, water, or snow - and proved remarkably successful in testing. Regardless, neither variant found interest with the USAF. Image via Ebay

The Last of the Bi-plane Gunfighters

Though the Gregor FDB-1 was born into a world where the monoplane was the drug of choice for modern air forces, there are several biplane fighters that came on the scene at the same time as the Gregor, yet went into production in considerable quantities. The difference between the Gregor and aircraft like the Fiat Falco, Gloster Gladiator, Grumman F3F and the Polikarpov Chaika, was that these aircraft were developments of older biplane fighters that had proven themselves already and were already in service. These aircraft were at the end of their development lives whereas the Gregor was just beginning its possible development, and the world was not seeing double anymore. All four of the competing aircraft types mentioned here, while displaying some positive qualities in the right hands, proved to be outclassed by modern monoplane fighters. All were relegated to non-frontline duties by the middle of the war.

The chunky Grumman F3F, was the last American biplane fighter aircraft delivered for service with the United States Navy, serving with Navy and Marine units in the late 1930s. It was never given an official name by the Navy or Grumman, but was lovingly referred to by its pilots as the Flying Barrel. Designed as an improvement on the single-seat F2F, it entered service in 1936. It was retired from front line squadrons at the end of 1941 before it could serve in the Second World War, and was first replaced by the Brewster F2A Buffalo. The F3F which inherited the landing gear configuration first used on the Grumman FF which was similar to that of the Gregor FDB-1. This particular Grumman F3F operated with US Navy Squadron VF-4 aboard USS Ranger. Photo: US Navy

The Fiat CR.42 Falco was a single-seat sesquiplane (lower wing less than 50% of the area of the upper wing) fighter which served primarily in Italy's Regia Aeronautica before and during the Second World War. The aircraft was produced by the Turin firm, and entered service, in smaller numbers, with the air forces of Belgium, Sweden (seen here) and Hungary. With more than 1,800 built, it was the most widely produced Italian aircraft to take part in the Second World War. The Fiat CR.42 was the last of the Fiat biplane fighters to enter front line service as a fighter, and represented the epitome of the type. Photo via ipmsstockholm.com

The biplane fighter with the most similar DNA to the Gregor FDB was the Russian Polikarpov I-153 Chaika. It first flew in a year before the Gregor (1938) and equipped the air forces of the Soviet Union, Finland (seen here in the Finnish Air Force's blue swastika makings) and China. It too had retractable undercarriage and a top gull-style wing. The name Chaika is a nod to this elegant and distinctive gull wing, as it is Russian for seagull. Unlike the single Gregor built, the Chaika was built in huge numbers–nearly 3,500 in all. It was considerably heavier than the Gregor and its its Shvetsov M-62 radial engine had much less power. One has to wonder how well the Gregor could have performed if it was fully developed.

The Gloster SS.37 Gladiator was a British-built biplane fighter which first flew in 1937. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s. Nearly 750 of the rigged fighter were built. It was the RAF's last biplane fighter aircraft and, like the Gregor, it was rendered obsolete by newer monoplane designs even as it was being introduced. Though often pitted against more formidable foes during the early days of the Second World War, it acquitted itself reasonably well in combat. Like the Polikarpov Chaika, it too was used by the Finnish Air Force. The Portuguese Air Force was using them until 1953. In the hands of a skilled pilot against lesser pilots, it was effective. The South African pilot Marmaduke "Pat" Pattle shot down 15 Italian aircraft using the Gladiator, making him the highest scoring ace on the type. Photo via http://www.1000aircraftphotos.com