TWO BY MOONLIGHT

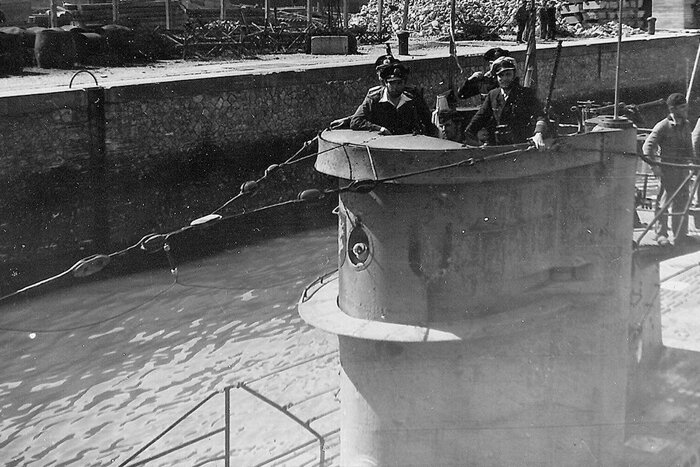

In the early hours of 6 June 1944, the Allied invasion of Normandy, which had been in the planning for years, took the Germans by complete surprise, despite the massive buildup on the littoral of southern Great Britain. This surprise was an advantage that could not be squandered by allowing attacks from the air and the sea on the supply line to the beachheads. Success required absolute air and sea superiority. On the seas, supply, trooping and combat vessels had no real threat from German capital ships, but U-boats and S-Boats (Schnellboote —the fast attack torpedo vessels called E-boats by the Allies) were another matter. As soon as the Germans understood that the invasion was on, Schnellboote from Cherbourg were the first Kriegsmarine combat vessels to engage the invasion fleet. Once they realized the immensity of the fleet, they let go their torpedoes from a distance and left the area. But soon, Schnellboote and their underwater counterparts, the Unterseeboote would swarm out of their pens along the French coast like angry wasps.

At the time of the landings, there were close to three dozen U-boats in pens on the coast of the Bay of Biscay (Bordeaux, Brest, La Rochelle, Lorient, and Saint-Nazaire), others returning from patrols and still others ready to sail from northern submarine bases in Norway (Bergen, Hammerfest, Kirkenes, Narvik, and Trondheim). The threat posed by all these U-boats and S-boats was taken very seriously and the task of sweeping the approaches to the English Channel and preventing the swarm from breaking through fell to the crews and aircraft of Coastal Command and in particular 19 Group of the Royal Air Force.

19 Group in the summer of 1944 was a massive organization, with five Liberator squadrons (53, 206, 224, 311, 547); three Handley-Page Halifax squadrons (58, 502, 517 (meteorological)); three Bristol Beaufighter squadrons (144, 235, and 404 RCAF); seven Vickers Wellington/Warwick squadrons (172, 179, 282, 304 (Polish), 407 RCAF, 524 and 612); four Short Sunderland squadrons (201, 228, 461 RAAF, 10 RAAF); one Mosquito squadron (248); two Fairey Swordfish squadrons (816 and 838 Squadrons, Fleet Air Arm); two Grumman Avenger squadrons (849 and 850 Fleet Air Arm) and four US Navy Consolidated Privateer squadrons (VPB-103, 105, 110 and 114). The group was spread out across 11 Royal Air Force bases in Devon and Cornwall (St Eval, Davidstow Moor, Chivenor, Predennack, Portreath, Mount Batten, Perranporth, Harrowbeer and Dunkeswell) and in Wales: (St. David’s, and Pembroke Dock). From the night of 5–6 June, 19 Group stepped up their patrols and successfully kept the U-boats from molesting the invasion ships—but not without cost.

7 June 1942—RAF St Eval, Cornwall

Throughout the long day of 7 June 1944, six 224 Squadron Coastal Command Liberator GR-V (B-24) crews, comprising 60 young men of the Commonwealth, left Royal Air Force Station St Eval on the north coast of Cornwall, England and headed towards the Celtic Sea or the Bay of Biscay. The first to leave on the 7th for its assigned patrol (actually the last of the previous night’s patrols) was 224 Squadron Liberator “B-Baker” (BZ915) commanded by 21-year-old Australian Flying Officer Ronald Henry Buchan-Hepburn (of Atherton, Queensland) and his largely Aussie crew. They were “wheels in the wells” at 34 minutes past midnight, thundering into the dark night sky bound for Operation CORK—the Allied attempt to stop the inevitable waves of U-boats rushing from the pens of the French coast submarine bases like Brest, La Rochelle, Lorient and Saint-Nazaire to interfere with Allied supply ships feeding the invasion beachheads.

An aerial photograph of RAF St Eval taken from about 10,000 feet on 18 July 1942. St Eval, situated along the northern coast of England’s Southwest Peninsula, was originally built in the late 1930s as a large grassy landing field with aircraft able to land into the wind at all times. However, rainy coastal weather meant that the field was soggy and unsuitable for operations much of the time. In the spring of 1940, a 1,000 metre paved runway and two intersecting shorter ones were built. A ring taxiway allowed aircraft to reach the start of the operational runway without interfering with landings and takeoffs. St Eval’s littoral location made it a natural base for Coastal Command aircraft patrolling the Bay of Biscay and the Western Approaches. The airfield supported Spitfire operations during the Battle of Britain and after the war it was an Avro Shackleton base. If one looks closely there are three things of note in this image. First, there are a number of multi-engine aircraft distributed across the infield grass. Secondly, the infield grass is divided into separate farm fields. These fields were not visible in earlier aerial photographs and the dark dividing lines also cross runways indicating camouflage designed to hide the larger field. And finally, one can see the craters of Luftwaffe bombs as well as damaged hangars, the result of raids in the summer of 1941. Photo: Wikipedia

An obviously staged shot of mechanics swarming a 224 squadron B-24 Liberator at RAF Beaulieu getting her ready for a patrol in December of 1942. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

In a more candid photograph, 224 Squadron mechanics work on the 1,200 hp Pratt and Whitney turbo-supercharged R-1830 Twin Wasp radials while in the background another Liberator rolls up to the dispersal at RAF St Eval on the northwest coast of Cornwall. This was in February of 1944, four months before the legendary actions on the night of 7–8 June 1944. Photo: Comox Air Force Museum Collection

As part of the Normandy invasion plan, Coastal Command Liberators including those of 224 Squadron were tasked with detecting, hunting down and destroying U-boats in the South Western Approaches and Bay of Biscay area and “corking” the western entrance to the English Channel, while to the northeast, Coastal Command aircraft set up search patrols to detect and sink Kriegsmarine surface ships like fast S-Boats. Together, the aircraft of Coastal Command were to seal off both ends of the English Channel from harassing submarines and torpedo boats.

Buchan-Hepburn and his men took off into weather that was agreeable to a long-range bomber crew operating over the sea and at low altitudes. The night was cloudy with light and intermittent rain, but becoming fairer as the hours crept along. The cloud would begin to break up during his patrol. Despite the good hunting weather, Hepburn failed to return to base. The last signal from “B-Baker” came just after 2 a.m., when she radioed that she was attacking a target off the French Coast near the island of Ushant, a French Channel Island near Brest, Brittany. U-boat historical sources indicate that this may have been U-415 under the command of Oberleutnant Herbert Werner, which was returning to base after having been damaged by a Wellington just a few minutes before. No trace was ever found of the nine brave men (Buchan-Hepburn, Flight-Sergeant Geoffrey John Fairs, Pilot Officer Philip William Hogan, Flight Sergeant John Downton Whitby, Flight Sergeant Max Elwin Dickenson, Flight Sergeant Bruce Alfred Hands, Flight Sergeant Albert Alexander Kennedy, Flight Sergeant Harold John Earl, Flight Sergeant Leonard James Barnes and Sergeant Arthur Collins), seven of which were a long way from their Australian home. U-415 would sink as a result of contact with a mine a month later outside the torpedo nets of Brest.

The Buchan-Hepburn crew was not the only 224 Liberator crew to disappear into thin air on the morning of 7 June 1942. At 9:40 p.m. on D-Day, just a couple of hours before Buchan-Hepburn’s Liberator took off, Liberator “M-Mike”— flown by 25-year-old American Flying Officer Ethan Allen and his crew took off from St Eval, climbed into the night, and were never heard from again. The crew was highly experienced—Flying Officer Ethan Allen, DFC (RCAF) of Tujunga, California and a direct descendent of American Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, pilot; Pilot Officer Morris Edgar Hayward (RCAF) of Vancouver, second pilot; Flight Lieutenant William James Esler (RAAF), Navigator; Flying Officer Howard Edgar Pugsley, Navigator; Flight Lieutenant Leslie Roy Aust, DFM, DFC; Warrant Officer High McIllaney, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Sergeant Douglas Edward Froggatt, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Sergeant John Andrew Mitchell, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Sergeant Alexander McLaughlin, Air Gunner; Sergeant John Brown Callan Gray, Air Gunner; Sergeant Alan Ridley Croft, Flight Engineer. This night would certainly be a time of tragedy and triumph for 224 Squadron, but they would not know of either until it was all over.

The first of six 224 Squadron Liberator Vs to take off on Wednesday, 7 June 1944, was “B-Baker” (BZ915) flown by 21-year-old Flight Lieutenant Ronald Henry Buchan-Hepburn, RAAF, a native of northern Queensland, Australia. It is not known for certain, but it is likely that he and his crew were lost when shot down by return anti-aircraft fire from U-415. No trace was ever found of the aircraft or the men. Though he took off on 7 June, Buchan-Hepburn’s “Lib” was actually the last aircraft of the previous night’s sorties, leaving shortly after midnight. His failure to return likely was the reason the first of the next day’s planned sorties left in daylight and several hours before the rest. Buchan-Hepburn was trained in Canada under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Photo: Australian War Memorial

The daylight hours at St Eval were spent with ground crews preparing five more Liberators for night patrols over the Bay of Biscay. Around 4 p.m. that afternoon, the first of these, Liberator “S-Sugar”, flown by 224’s commanding officer, Squadron Leader Maechel A. “Mick” Ensor DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar, lifted heavily from St Eval’s runway, bound for an anti-U-boat patrol in the Southwestern Approaches. Ensor, a New Zealander (as were two other members of his crew), was one of the true heroes of Coastal Command and likely part of his mission was to search for signs of Buchan-Hepburn’s Liberator and crew, which were long overdue.

Fourteen hours after Buchan-Hepburn’s departure and 12 hours after the last radio call received from “B-Baker”, the squadron commander “Mick” Ensor took off in “S-Sugar” for his patrol area and possibly to search for his two lost crews. New Zealander Squadron Leader Maechel Anthony Ensor was a highly decorated veteran of Coastal Command with two Distinguished Service Orders, two Distinguished Flying Crosses and an Air Force Cross. Here he poses with a 224 Squadron “Lib” and his Border terrier dog named “Liberator”. Photo: www2awards.com

“Mick” Ensor and eight members of his crew pose with a 224 Squadron Liberator. Ensor is second from left, holding his dog “Liberator”. While unable to identify who is who in this image, here are the members of Ensor’s crew who took part in Operation CORK on the night of 7–8 June 1944: Squadron Leader Ensor (RNZAF), Flying Officer W. Andrews (RNZAF), Flight Lieutenant F.F. Addington, Flying Officer R.G. Tate, Pilot Officer D.M. Muir, Sergeant T. Cockeram, Flying Officer A.G.R. Pugh (RNZAF), Sergeant R.G. Plummer, Flight Lieutenant S.R. Carter and Sergeant W.G. Moses. Photo: Comox Air Force Museum Collection

As darkness crept in on the evening of 7 June, four more crews took their seats aboard their Liberators and began the technical litanies that would bring to life their war machines. These were to be long, over water night missions of 10+ hours duration—challenging, dangerous and hopefully fruitful. Despite advanced technologies like High Frequency Direction Finding, better radars and high-powered Leigh searchlights used by the RAF to find them, the U-boat captains of the U-Boot-Waffe flotillas based along the great curving coast of the Bay of Biscay still preferred to run on the surface at night to recharge rather than by day. The waters here would prove to be a choke point for the Germans, with contacts and attacks made by all crews throughout the coming night.

At 23 minutes past 8 that evening, with the sun soon to set over the Irish and Celtic Seas, Pilot Officer W.D. Jones in Liberator “D-Dog” pushed his fistful of throttles to takeoff power and lumbered down the runway into the late evening sun, lifted off and turned for the Southwestern Approaches. In his crew were four Canadians. Over the next few hours and on into the night, the other four Liberators would launch for their assigned patrol areas at the bottom of the English Channel and into the Bay of Biscay. Flight Lieutenant Norman Bradley Merrington, DFC, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (with five Aussies in his crew) took off in Liberator “N-Nan” at 20 minutes before 10 o’clock in total darkness, his nav lights and exhaust flames disappearing into the soon to be full moon night. This was weather perfectly suited to the hunter. Radar could pick out a target from more than 10 miles, and pilots could manœuvre to put the submarine up-moon, where the silhouette of its conning tower could easily be seen.

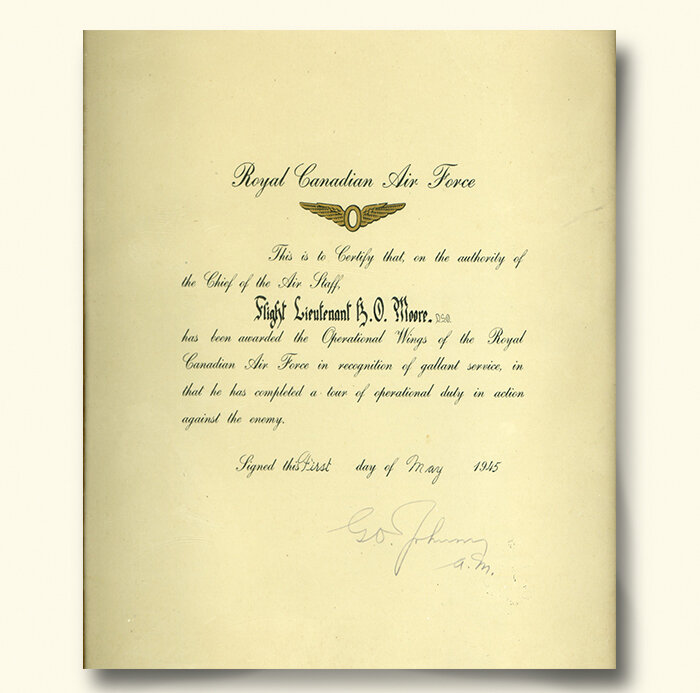

Half an hour later, a 22-year-old Canadian by the name of Flying Officer Kenneth Owen Moore, known as “Kayo” to his friends and crew, nodded to his co-pilot Flying Officer J.M. Ketcheson and together they pushed the four throttle levers to takeoff power in Liberator “G-George”. Stooped between them was Flight Engineer Sergeant James Hamer, RAF, calling out airspeeds and monitoring engine instruments. In addition to the two pilots, five others in the aircraft were members of the Royal Canadian Air Force. As they made for the Bay of Biscay, the crew began their search for targets, not knowing just how successful they would be by the time the sun came up the next day. More on their adventures later.

A beaming Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Owen Moore, DSO sits in the left seat of his 224 Squadron Liberator GR-V. Despite his smile and being just 22 years old, Moore shows the weight of command in his eyes. Moore’s obituary 66 years later in 2008 stated “A natural leader, his unselfish, compassionate and understated strength touched everyone’s life.” That too is visible in these very same eyes. Moore learned to fly within the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, completing his first solo and Elementary Flying Training syllabus at No. 6 EFTS, Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, just a hundred miles from his Rockhaven, Saskatchewan home. He was selected for the challenges of multi-engine flying and was sent to No. 5 Service Flying Training School in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan where he earned his wings on the twin-engined Avro Anson. It was fortunate for a Saskatchewan farm boy to do all of his air force flight training so close to home. This included his basic air force training at No.7 Initial Training School in Saskatoon as well. He was never more than a short train ride from home. Moore’s comfort with long flights over flat expanses of water may have a founding in living and training on the wide-open prairies of his beloved Saskatchewan. Photo: Comox Air Force Museum

Just before midnight on the 7th, “C-Charlie”, the last 224 Squadron Liberator to take off that day, thundered down the 1,000-metre runway at St Eval and into a clearing night sky, with the full moon looming over Cornwall. At “C-Charlie’s” controls was Flight Lieutenant J.E. “Jimmy” Jenkinson of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. These Liberator launches were just those that took place on 7 June 1944. During the ensuing patrols of the last five of these aircraft, 224 Squadron launched two more in the first hours of the morning of 8 June and would continue the steady pressure, putting assets in the air over the approaches to the channel for many weeks.

Kriegsmarine U-boat captains remembered wistfully the First and Second “Happy Times”, when they roamed largely unmolested in the shipping lanes between Halifax and Liverpool. Convoys bound for Liverpool faced being ravaged by torpedo attacks from wolf packs that lay in wait. But by May 1943, known to the U-Boot-Waffe as “Black May”, three critical and interlaced systems that had been put into place by the British, Canadians and Americans finally began to pay dividends, turning the hunters into the hunted. The first was “Huff-Duff” or High Frequency Direction Finding (HFDF), a radio direction system that could triangulate on the radio transmissions of U-boats as they made contact with headquarters in Lorient, France. This enabled convoys to be vectored away from concentrations of German submarines, and aircraft to be vectored towards them. The second system was Asdic or sonar, which allowed escorts to find submerged submarines and hunt them with depth charges. During the first years of the war, these first two systems, working in concert, helped considerably to reduce the carnage, but there was always a large gap in the middle of the Atlantic that was not effectively patrolled by aircraft (Wellingtons, Whitleys, Hudsons and the like) from either coast until the advent of long-range Coastal Command Liberators and Short Sunderlands. The Consolidated B-24 Liberators were relatively inexpensive, had very high endurance and, operating from bases in Canada, Iceland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the South of England, were able to cover the entire Atlantic. Day or night, U-boat crews surfacing their boats in the mid-Atlantic to recharge batteries or communicate with Lorient now felt the pressure of a possible attack from the air. In this photograph, a 224 Squadron Liberator Mk III is photographed flying back to its base at RAF Beaulieu, Hampshire on the south coast of England near Lymington. 242 Squadron flew from both Beaulieu and St Eval, a 19 Group Coastal Command base on the Southwest Peninsula of Great Britain. Photo: Imperial War Museum

224 Squadron maintained a steady stream of Liberators over the operational area, as did all of the other squadrons of 19 Group, with relatively large numbers of aircraft aloft at any given time. By this time in the U-boat war, even Oxford and Cambridge mathematicians were contributing to the war effort. The aerial pressure exerted by the RAF was the result of complex statistical analysis by these mathematicians. The Bay of Biscay was a choke point for U-boat operations, with U-boats forced to leave and return across this large body of water as they made for the submarine pens along the south coast of France. It was also known that U-boats could not possibly cross it underwater at one go and that they would eventually have to surface to recharge their batteries and freshen their air, and move faster on the surface. Statistically, this meant that at any given time (especially in the hours of darkness) there was always a calculable number of U-boats running on the surface somewhere on the Bay of Biscay and within reach of shore-based flying assets. If the RAF could commit enough aircraft, keep them aloft long enough and in set search patterns, the mathematicians calculated correctly that they could sink U-boats at a predetermined rate. Long-range aircraft like the Liberator, combined with more advanced technologies like new radar sets and Leigh Lights (powerful wing-mounted searchlights), could pick up submarines on the surface from miles away. The U-boats sunk here were as much the victims of the “boffins” as they were of the brave aircrews that hunted them down.

Buchan-Hepburn and crew disappeared around 2 a.m., their fates known only to the bright full moon and the cold waters of the Bay of Biscay. Mick Ensor in “S-Sugar” returned to St Eval at 2:33 a.m. on 8 June after a 10.5 hour-long patrol, having made an attack on a U-boat with 8 of his depth charges as well as machine gun fire from his rear turret.

Five hours later, Merrington in “N-Nan” brought his Liberator in after sunrise at 0724 hrs, having patrolled for close to ten hours with nothing to show for the effort save the sighting of fishing boats under sail. Not long after him, Jones landed “D-Dog” at 0741 hrs after a grueling 11.5 hour-long patrol with naught but fishing smacks caught in his radar. The exhausted crew could only have been disappointed in having nothing to show for the punishing patrol.

I hunted the web for images of the 224 Squadron pilots who launched on 7 June 1944 to help illustrate the squadron’s efforts on the night of 7–8 June. Ensor, Buchan-Hepburn and of course Moore were found; Jones and Jenkinson could not be found (yet) and Norman Bradley Merrington’s image was elusive even though he was part of a later piece of early cold war history. After the war, Merrington found employment as a civilian airline pilot with British European Airways (BEA), a new carrier that got its start in 1946. As a co-pilot aboard Vickers Viking VC-B G-AIVP (similar to the one pictured above), he was killed in an air crash known as the Gatow Air Disaster. On 5 April 1948, while on final into western Berlin’s RAF Gatow air base, Merrington’s Viking with four crew and ten passengers aboard was buzzed by a Soviet Yak-3 fighter. At approximately 2:30 p.m., while the Viking was in the airport’s safety area levelling off to land, the Yak-3 approached from behind. Eyewitnesses testified that as the Viking made a left-hand turn prior to its approach to land, the fighter dived beneath it, climbed sharply, and clipped the port wing of the airliner with its starboard wing. The impact ripped off both colliding wings and the Viking crashed inside the Soviet Sector, at Hahneberg, Staaken, just outside the British Sector and exploded. The Yak-3 crashed near a farmhouse on Heerstrasse just inside the British sector. The occupants of both aircraft died on impact (Wikipedia). Photo: VickersViscount.net

The New Zealander Jimmy Jenkinson touched down last after nearly 11 hours on patrol. He had a busier night than Merrington and Jones, being attacked at 0130 hrs by anti-aircraft fire and then attempting to maintain contact with a small convoy of vessels escorting what appeared to be a submarine. During his attempted attack, Jenkinson was fired on and fired back with 200 rounds from his rear turret and 50 from the starboard waist gunner. He suffered no damage and tried unsuccessfully to re-establish contact with the ships, breaking off finally at 0346 hrs. At 10 a.m., he called off his patrol and made haste for home. Sadly, Jenkinson and his entire crew were lost four days later on their next U-boat patrol while making an attack on a surfaced U-boat near the small island of Ushant.

Of course, one other Liberator was out on the water that night, “G-George” under the command of Flying Officer Ken “Kayo” Moore. Out of depth charges, he ended his patrol an hour and half early and landed back at St Eval at 0709 hrs with an amazing story to tell.

Two by moonlight—the story of “G-George”

A crew of a Coastal Command Liberator GR-V required 10 men to work as a team. Unlike British-built heavy bombers, American designers built the massive slab-sided “Lib” to be flown by a pair of pilots. Moore’s co-pilot in “G-George” was another Canadian, Flying Officer J.M. Ketcheson, who helped Moore with the flying on the long, grinding flights. Monitoring engine performance, fuel consumption and other engine, electrical and hydraulic instruments as well as conducting walk-around inspections was the flight engineer, Sergeant J. Hamer, a native of Great Britain. Of course, long patrols over vast expanses of open ocean required the very best navigators to keep on the planned search pattern and to get everyone home safely. The navigator on Moore’s crew and on the night of 7 June was Warrant Officer Johnston “Jock” McDowell, Royal Air Force. Actually, these long flights with complex course corrections over 10–12 hours required two navigators. The second navigator aboard “G-George” was Flying Officer Alec Paddon Gibb, DFM, of Saskatchewan.

A big multi-engine bomber like the Liberator V required a number of gunners to man the nose gun, waist guns, top turret and rear turret as well as be qualified to operate radios and radars. Unlike the guns in Liberators used for strategic bombing, the machine guns aboard a Coastal Command “Lib” were more often offensive weapons than defensive. Gunners in the nose and top turrets could rake conning towers and deck gun crews on the run-in, while waist gunners and rear gunners could keep the U-boat crew’s heads down as the Liberator climbed after dropping depth-charges. Many U-boat crews suffered serious casualties inflicted by the gunners of attacking bombers. “G-George” and Kayo Moore’s crew included five such Wireless Operator Air Gunners—Warrant Officer D.H. Griese, RCAF; Warrant Officer E.E. Davison, RCAF, Warrant Officer William Peter Foster, RCAF of Hamilton, Ontario; Warrant Officer Mike Nicholas Werbiski, DFM of Rockton, Manitoba and Flight Sergeant I.C. Webb (called Webber by Moore in later statements).

A superb photograph of Moore’s crew taken on the very day they made history—8 June 1944. They are (Back row, left to right) Warrant Officer Jock MacDowall, DFC, Navigator, Flight Sergeant I. C. Webb, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Flying Officer Ketcheson, Second pilot; Warrant Officer E.E. “Ernie” Davison, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Sergeant J. Hamer, DFM, Flight Engineer; Warrant Officer D.H. Griese, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner. Front row: Pilot Officer Al P. Gibb, DFC, one of two Navigators; Warrant Officer Mike Werbiski, DFM, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner; Flying Officer Kenneth Own Moore, Pilot; Warrant Officer William P. Foster, DFC, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner (who had been operating the radar at the time of the attack). The identities of the men are from a caption written on the back of the photo. Photo via www.richthistle.com

Then Flying Officer Kenneth Owen “Kayo” Moore (left in front row) poses with eight members of his 10-man crew who were involved in the sinking of two U-boats on the night of 7–8 June 1944. In the very front is Moore and crew’s lucky stuffed Panda “Warrant Officer Dinty Moore”, named not after the popular Dinty Moore canned stews from Hormel, but likely after a Canadian hockey player named Frank “Dinty” Moore who played on the 1936 Canadian Olympic team in Garmisch–Partenkirchen, Germany. This photo, with the men out of their flight gear, was clearly taken at a later time than the previous photo. Photo: Comox Air Force Museum Collection

After taking off into the night sky at a quarter past ten on the 7th, Moore climbed and made a long turn to take his Liberator back across Cornwall and the slender neck of the Southwest Peninsula of Great Britain. He did not have to climb very high, for a Coastal Command Liberator carried out its operations at very low level compared to the Lancasters and Halifaxes of Bomber Command. This patrol would be flown at an average operational altitude of just 500 feet ASL, but perhaps Moore climbed a little higher as he transited Cornwall for safety and comfort reasons. Low-level ops had their benefits and their dangers. For one, they would not need the oxygen masks that sustained Bomber Command crews at 20,000 feet or more, nor would they need the heavy, cumbersome, electrically heated clothing of their strategic bombing brothers. It was June and the temperatures, in the 50s F, were just below seasonal. They would, however, be flying the entire patrol at 500 feet or below where the mechanical turbulence could be uncomfortable and prolonged.

At 500 feet, there lay other dangers as well. Any lapse in attention or judgment, serious mechanical problems, icing or combat damage that resulted in a temporary loss of control could very well spell fatal disaster as there would be no altitude for recovery. Physically demanding, monotonous 11 to even 15-hour patrols over an infinitely repetitive ocean could wear down the crew of a Coastal Command aircraft. On Sunderland flying boats there was a galley and even bunks on Cansos, but the Liberator had no provisions for comfort. It was best to get to work and put thoughts of comfort from your mind.

In their bomb bay, the ground crews had uploaded twelve 250-pound cylindrical Mark XI Torpex depth charges, set to detonate just below the surface, for they were hunting for surfaced U-boats only. They also carried a single 600 lb. air-dropped acoustic homing torpedo for anti-submarine work. It is listed in the weapons load for “G-George” in the ORBs under the code name “proctor”.

Armourers at RAF St Eval manhandle 250 lb. depth charges from a bomb trolley as they prepare a Liberator GR Mark VA of 53 Squadron for a patrol. Moore’s “G-George” was loaded with twelve of the cylindrical weapons as well as a 600 lb. acoustic homing torpedo. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Their assigned operational area was “Patrol E”, which would take them to the eastern reaches of the Bay of Biscay. Passing over the south coast of England, Moore would have brought “G-George” down to its operational altitude and everyone would have been on alert. Warrant Officer Foster would have had the radar turned on and, despite not being in their assigned area yet, everyone would have settled into their roles, professional, alert, quiet—for even in transit, they were searching for the enemy. The gunners likely checked their weapons with short bursts into the night. It would be a full 45 minutes before they were on station in Patrol E, arriving there a couple of minutes after 11 p.m. that night. The full moon was just rising above the Bay of Biscay and the water shimmered like burnished armour under its powerful light. There was scattered cloud above them, with the moon racing bright among the “two tenths cu”. These were conditions well suited to the hunter, and the U-boat captains knew this, but they were in a rush to get to the ships in the English Channel and even if they were running submerged, they would just have to come up for air and to charge their batteries. Type VIIC U-boats could manage nearly 18 knots on the surface, but only 7.5 beneath. Running on the water was extremely risky close to Great Britain, but there were times when this was necessary.

“G-George” droned on through the night. Men drank coffee from thermos flasks, kept the chatter to a minimum, scanned the endless sea and began to feel the numbing weariness set in that came with these long over-water patrols. But adrenalin shot through their bloodstreams like amphetamine just after 2 a.m. when Foster announced on the intercom that he had a solid return on his radar 12 miles dead ahead in the vicinity of Ushant Island (Ouessant). It was too early to tell whether it was a French fishing smack or the conning tower of a U-boat. Moore corrected his course slightly to port to put the target in the path of the moon reflecting on the water. Three miles out the conning tower of a submarine was made out in the moonlight.

Coastal Command anti-submarine crews were trained to attack the moment a U-boat was detected and without deliberation. An undamaged Type VIIC U-boat, with a well-trained crew could crash dive beneath the surface in 30 seconds. Time was of the essence, as was complete surprise.

Immediately, Moore instructed Foster to switch off the radar in case the submarine had detection equipment, and then began to drop lower and lower, adjusting his course to keep the enemy up-moon until he was at 50 feet above the calm surface. McDowall, the navigator, took his position at the bomb sight. Moore ordered the four big bomb doors opened and as they slid upwards and outboard on their rollers, he could hear the hydraulic pumps working and sense the difference in the airflow note down the sides of his warhorse. Approaching the U-boat, which they calculated was making 10–12 knots in a westerly direction, they selected 6 depth charges from their quiver, attacking due south and 90 degrees to the path of the U-boat on her starboard side. Moore chose to leave the powerful 22 million-candela Leigh Light off to further keep their whereabouts secret. As they screamed in for the attack, the spare navigator, Pilot Officer Alec Gibb, DFC sprayed the conning tower with heavy machine gun fire (some 150 rounds according to the after action report) from his position in the nose. Moore and Gibb later stated they could see as many as 8 submariners scrambling from the tower to get to the deck guns. There was some anti-aircraft return fire, but it was too little and too late. They had caught them completely by surprise.

As they roared over the submarine at 190 mph, six depth charges, set 55 feet apart, were falling from “G-George’s” bomb bay, having been released by McDowall whose accuracy this night would be perfect. Three fell on either side of the submarine in a textbook straddling attack just ahead of the conning tower. A flame-float, designed to ignite when it hit the water was also dropped to identify the position of the submarine at the moment of attack. The rear gunner Flight Sergeant I. Webb watched in fascination as the detonations exploded white in the moonlight and appeared to lift the 700-ton submarine out of the water.

By the time they had climbed, swung around and were homing on the beacon of the flame float at the position of the attack, there was nothing left of the U-boat save for some floating wreckage and the oily slick of diesel fuel. A Type VIIC U-boat had disappeared and ceased to exist in a matter of seconds, the depth charges having done their job breaching the pressure hull and sending one of Karl Dönitz’ hunters to the bottom with all hands. One can only imagine the last minutes of terror for the more than 50 men aboard.

Sadly, when this submarine sank, there was no one who could identify which U-boat it was. Postwar accounting pointed to U-629, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Hans–Helmut Bugs on its 11th war patrol. She had just slipped out of her pen at Brest the day before. Still, other researchers disclaim the U-629 identification, pointing instead to U-441, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Klaus Hartmann on its ninth and final war patrol. It is not my goal to be definitive as to the identity of the fifty or so men killed that night, that best being left to experts in the field. Knowing would bring the story to a satisfying close, but it will not lessen the tragedy or the courage of the U-boat men who died that night.

The first submarine to be sunk by Moore sank rapidly following the attack, taking with it to the bottom not only her full crew, but her identity as well. This submarine has been identified by different sources as either U-629 or U-441, both of which were lost under uncertain circumstances in June of 1944. I won’t get into making a determination of the sub’s identity, leaving that to the experts, but perhaps we should know a little bit about both U-boats and their crews, for in this will be found the truth. U-629, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Hans–Helmuth Bugs was on its 11th war patrol, having slipped out of the pens at Brest on 6 June 1944 (D-Day), likely bound for the Normandy coast and the English Channel. Bugs (above left and at left in right photo) was with U-629 through its launch and commissioning and was a seasoned veteran commander. Like U-373 (the second U-boat attacked by Moore that night), which would leave port the following day, Bugs’ U-629 had just completed repairs after having been seriously damaged by an RAF Coastal Command Wellington of 612 Squadron on 12 March. At that time, U-629 was only a day out of Brest and was forced back to base to affect repairs to her heavy damage. Nearly three months later, her next attempt to cross the Bay of Biscay would result in her sinking with all hands. The repeated attempts and ultimate fates of both U-373 and U-629 illustrate the severe threats to U-boat operations presented by 19 Group anti-submarine bombers. Photos: Left: uboote.fr; Right: uboat.net

U-441, a Type VIIC U-boat of the 1st Flotilla in Brest, was commanded by Kapitänleutnant Klaus Hartmann (top left), a 32-year-old veteran who was with U-441 during its construction in late 1940 and launch in late 1941 in Danzig. At one point, U-441 was one of just four U-boats fully converted as a “flak boat” with extended “winter garden” and gun platforms. Equipped with two 2-cm quad anti-aircraft machine guns (upper right), a 3.75 cm machine gun (at far left in lower photo) and additional MG 42 machine guns, U-441 and the others were designed as surface escorts for incoming and outgoing attack U-boats transiting the Bay of Biscay. Called “aircraft traps”, they were intended to lure Coastal Command anti-submarine aircraft and shoot them down. The concept worked well at the outset, with U-441 luring a lumbering Short Sunderland to its death but RAF pilots soon learned to keep their distance and attack in numbers. A flight of Beaufighters attacked U-441 and heavily damaged her, killing 10 and wounding 13 including Hartman. The experiment was cancelled and U-441 and the others were converted back to the traditional deck gun and defensive weapons of a typical Type VIIC submarine. Middle right: the fanciful crest of U-441 as a Flak Boat showing a swordfish impaling a Coastal Command aircraft. It is widely thought that U-441 was sunk with all 51 crew members being killed on the night of 7–8 June 1944. It was the boat’s ninth and final patrol. Photos: U-boat.net

Moore settled his crew down after the last pass over the wreckage, and ordered a course correction to take them back on their patrol. At 0231, just twenty minutes after the first radar contact was made, “G-George” sent a message to command that they had sunk a U-boat. The men were charged with electricity, but they had a job to do and hours before they could return home to St Eval.

Just a few minutes later at 0240 hrs, as they settled down at 700 feet ASL, Foster reported another radar contact 10 degrees off the starboard nose, this time just 6 miles ahead. Moore, with information from Foster, began to home in on the target, and at 2.5 miles range and 75 degrees to starboard, they sighted the conning tower of another U-boat on a northwesterly course running at an estimated eight knots on the surface. This time Moore needed to circle to port and come in on a course that would allow them to attack up the moon path.

Bringing the big Liberator down to 50 feet once again, Moore approached the U-boat at 110 degrees to its starboard side with plenty of time to set up another perfect attack at 190 mph. The remaining six Torpex depth charges were released at 55-foot intervals as well as a flame float. Again, Gibb, the spare navigator in the nose, was firing his machine gun at the conning tower, which answered this time with flak and tracer fire. As they roared overhead, the rear gunner Webb saw four depth charges strike the water to the starboard side of the U-boat and two on the her port side—another textbook straddling attack. Massive flumes of exploding water were seen rising on either side of the submarine, ten feet aft of the conning tower and totally obscuring the target.

The attack on U-373 was another textbook straddling of the submarine with depth charges, just aft of the conning tower. By the time Moore had turned back to the position of the attack, the U-boat was already in its death throes. Photo Illustration by author

Returning to the position of the flame float, Moore, Gibb and Ketcheson saw the U-boat in the bright moonlight, with a heavy list to starboard. As they approached, the bow rose steeply out of the water to an angle of about 80 degrees. The boat slid back into the sea “amid a large amount of confused water” according to the 224 Squadron ORB.

Moore circled in fascination and, coming around again, he turned on the powerful Leigh Light slung beneath his starboard wing outboard of engine No. 4. The blinding blue-white beam illuminated three yellow dinghies crowded with men floating on an oily surface strewn with bits of wreckage. One can imagine how exposed the survivors must have felt caught in the white light of the Leigh with a heavily armed Liberator thundering down its beam toward them. They passed overhead without further molesting the surviving crew, switched off the Leigh Light and left the German sailors floating in the moonlight.

The submarine was U-373, another Type VIIC boat commanded by Kapitänleutnant Detlef von Lehsten on its 11th war patrol. It had just slipped out of Brest after a six-month repair following a similar attack by a Coastal Command Wellington and Liberator in January. We know for certain that this was U-373 because all but four members of the crew survived to be picked up the next day by French fishing vessels and returned to Brest. Von Lehsten was one of the survivors.

It is important to know that while the enemy was indeed the German U-boats, they were manned by extraordinarily courageous young men, everyone of them handpicked professionals. An astonishing 75% of all U-boat men were killed in the line of duty, many whose fate and final resting place were never known. Of all the services on either side of the war, the U-Boot-Waffe suffered the highest death rate—by a wide margin. It is important to uncover what we can of the history and crews of the two U-boats sunk that night by Moore. There is however some disagreement as to the identity of one of the submarines sunk on 7–8 June. This is of course because U-boats were often out of contact with Lorient for days and weeks—weeks when possibly several U-boats might be lost in the same area of operations, so determining date and time of a sinking was a postwar process of elimination in many cases. The one U-boat that was sunk for certain that night by Moore and his crew was the second one attacked—U-373, a Type VIIC submarine under the command of 27-year-old Kapitänleutnant Detlef von Lehsten (left) from Hamburg, Germany, a major U-boat production centre since the First World War. We know the identity of this U-boat from the simple fact that all but four of the crew survived. Von Lehsten was one of the survivors who were picked up the next day by French fishermen, but his chief engineer Leutnant Kohrgal Korger (right) was one of the four men who were killed in Moore’s attack. Photo: Coastal command’s Air War Against the German U-boat, Rare Photographs from Wartime Archives by Norman Franks, via Google Books

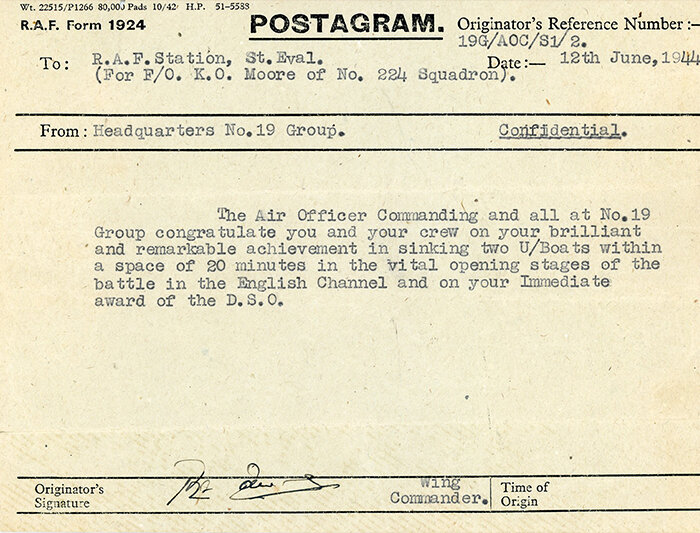

Moore ordered the crew to continue on its patrol, but emotions must have been very high in the confines of the Liberator. At 0330 hrs he sent a message to command stating “First U/boat 6 DC’s—straddle—sunk—oil and wreckage on surface”. At 0347 hrs, he sent a second message to command, stating: “Second U/Boat 6 DC’s—straddled—sunk—3 dinghies with survivors.” Still, he continued on the patrol. At 0524, with the morning light just beginning to brighten the eastern horizon and suspecting that they had a fuel leak, he radioed command with a simple message “R/B 0700”—returning to base, landing around 7 a.m. Moore left “Patrol E” at 0610 a.m. and turned for home with only the single proctor torpedo left in his bomb bay.

One can only imagine the scene now—the undamaged white Liberator, brilliant and dusted orange by the rising sun at their backs, thundering at 500 feet across the sea—in the cockpit Moore, Ketcheson and Hamer feeling more alive than they had ever felt in their lives, still electrified by the night’s work—the approaching coast of Cornwall lit by the morning sun over a calm blue sea, thin veils of morning mists still shrouding the line between sea and the green fields of Cornwall where white cottages shone like brilliant gems in the sunlight. In the rear turret, Webb would have been staring into the sun, always aware that a marauding Luftwaffe Ju 88 or Bf 110 could be following them, hiding in the sun’s glare. Though his men were feeling good, Moore would not allow them to be complacent, especially now, when they had made history.

At 7 a.m. on Thursday 8 June 1944, with the sun lighting up the 13th Century stone tower of St Eval Church, Moore brought “G-George” in over the threshold at RAF St Eval, and touched down. They were home.

For a Coastal Command crew, sinking a U-boat was the ultimate achievement, but it was a highly unlikely one. Despite the fact that there were many thousands of Coastal Command anti-submarine sorties during the war, only 249 U-boats were sunk by aircraft alone and this included carrier-based aircraft. A Liberator crew had a less than 1% chance of sinking a U-boat, so to sink two in a span of 20 minutes was a feat unmatched in the war. While there are pilots who sank more than one U-boat, no one before or since can claim two in one sortie.

Needless to say, there were people waiting for Moore and his crew when they taxied up to the dispersal. After the immediate celebrations, there were extensive debriefings by squadron intelligence people. The 224 Squadron ORBs are an extraordinary resource, far more expansive than most I have seen, with details pertaining to weather, surface conditions, course changes, times, radio calls, and narratives for all sightings, attacks and in the case of Moore, sinkings. In Battlefield Bombers, Deep Sea Attack, Martin Bowman describes one 224 Squadron airman meeting up with Moore walking out of the canteen with his crew: “His face, which might be described as rugged Canadian, incapable of false expression, was good to see. He was white with exhaustion but as excited as a child. “You’ve made history” was all that anyone seemed able to say. All the four thousand men and women on the station seemed to catch the spirit of victory and I have seldom seen so much jaunty walking or heard such whistling. Even the Group Captain, usually cool and self-controlled, was rushing about with the photographs of the attacks in his hand. I travelled back to the beach in the van with Kayo Moore, but he was too tired to talk. When we arrived at the mess, he went off to sleep. About three hours later I saw him carrying plates of fish and chips to the other members of his crew still in their beds.”

That is a true Canadian, I am proud to say.

Dave O’Malley, Vintage Wings of Canada