THIS IS IT!

In 1947, Pan American World Airways began the first regularly scheduled “Round-the-World” passenger service. Each day, a flight would depart from the East Coast (New York or Philadelphia), heading east towards Europe and another on the West Coast of the United States would lift off from San Francisco Municipal Airport and, heading west, fly the same route in reverse.

Passengers on these flights who had bought a “round-the-world” ticket could deplane from a Pan Am Clipper aircraft (by the mid-1950s, these were variously Douglas DC-6s and 7s and Boeing 377s in combination for each flight number) at any of the waypoint cities (in 1947: Honolulu, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Delhi, Istanbul, Frankfurt, London and New York) and stay as long as desired before continuing the journey. The only requirement was that the entire journey had to be accomplished within 180 days. If a passenger was to remain aboard the flight for the entire trip, and there were no technical or weather-related setbacks, he or she could be back in the United States in 48 hours.

These globe-trotting flights were partly promotional, putting Pan Am in the world spotlight and were only for the very wealthy. Tickets were $2,300 for a single economy passenger and $4,000 for a couple. With inflation, this translates into about $22,000 and $38,000 respectively. First class was considerably more, but one has to understand that Economy (or Tourist Class as it was known then) aboard a Pan Am Clipper was more luxurious, far roomier and had much higher service than Business Class has today. Due to these costs, many of the passengers on these flights were not round-the-world travellers, but simply business men, diplomatic families, and servicemen and women returning home or repositioning.

By 1956, these daily flights around the globe were old hat to the highly experienced cockpit and cabin crews of Pan American. While the waypoints around the world had changed somewhat, the system was sophisticated and well worked out, with maintenance and administration services in each city to deal with technical issues as well as passport and customs requirements. Of all the aircraft used on these runs, the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was undoubtedly the queen of the skies—for Pan Am and other operators in the Pacific and Atlantic runs like Northwest and United.

Pan American World Airways was the launch customer and largest purchaser of the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser long-range airliner which was a civil development of the C-97 Stratofreighter military cargo lifter and KC-97 aerial refuelling tanker (themselves derived from the B-29 Superfortress). Pan Am purchased 33% of the eventual production run of 56 airframes for $24,500,000, at the time the largest commercial aircraft order in civil aviation history. They called them StratoClippers in keeping with their traditions. By the mid-1950s, the roomy and reliable double-decked Stratocruiser had flown many millions of miles in “round-the-world” service, and, while the glamour was still there, the flights were largely routine. But not all.

On 8 November 1957, Pan Am Stratocruiser N90944 Clipper Romance of the Skies, known as Pan Am Flight 7, took off out of San Francisco International Airport on the first leg of her westward circuit of the globe with a final stop in Philadelphia. At 4 PM local time Flight 7 radioed United States Coast Guard Cutter Pontchartrain at Ocean Station November that she was on course at 10,000 feet and just ten miles to the east of the cutter. She was never heard from again. Flight 7’s 36 passengers and 8 crew members died in some unwitnessed and never-explained event sometime after that. Wreckage was found the following day some 90 miles to the north of her course line. Nineteen bodies were recovered, of which 14 were wearing life vests and had no shoes, indicating that passengers were prepared for an ocean ditching. Higher than normal levels of carbon monoxide were found in the bodies, possibly from smoke inhalation and foul play was suspected but never proven. It was one of those distressing civil aviation occurrences that made many people uneasy about flying at a time when flying was just beginning to become an everyday possibility for international travel.

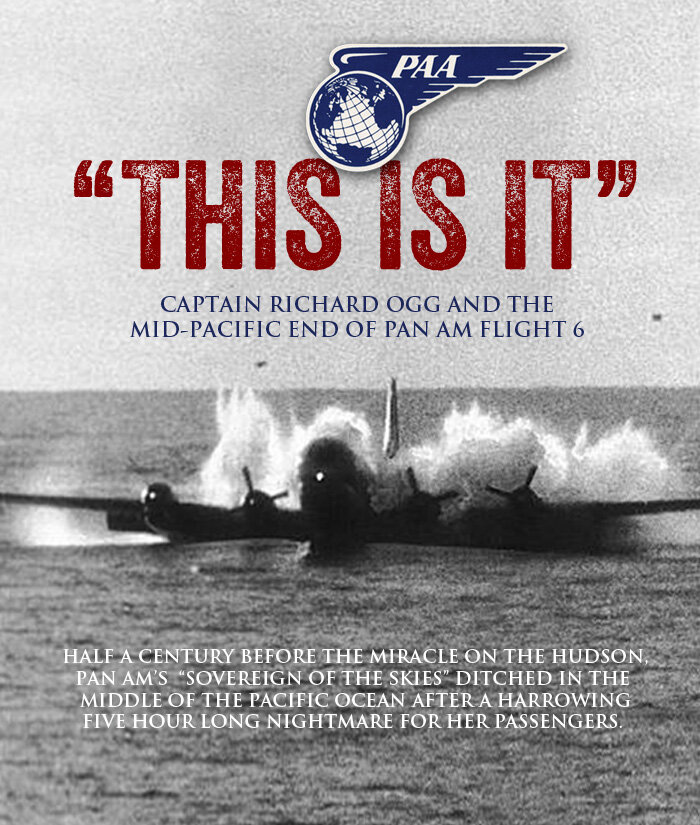

But it was the story of another “round-the-world” Pan Am StratoClipper—Pan Am Flight 6, the Clipper Sovereign of the Skies (N90943)—that truly captured the imaginations of the world. If Flight 7 brings up an upsetting comparison to the recent disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, the last flight of Pan Am 943 (its call sign, not its flight number) is eerily reminiscent of US Air Flight 1549, the famed Miracle on the Hudson.

Pan Am’s Flight 6 had originated in New York City days before on different equipment (Douglas DC-7). The complexities of the round the world routing and schedules are explained by CaliforniaAviation.org in their Pan Am Series of posts: “According to the April 1956 and July 1956 timetables, Flight 6 was part of Pan Am round-the-world service operating on Thursdays and Fridays as Flights 70/6 (all-Tourist Class) and Flights 100/6 (all-First Class) and on Fridays as 64/6 (combined First and Tourist). Flights 64 and 70 were operated with DC-7B or DC-7C equipment and Flight 100 was operated with a Boeing 377 Super Stratocruiser. Flights 70 and 100 operated from New York to London where Flight 6 took over with DC-6B equipment offering “Sleeperette” service. Flight 64 operated from New York to Beirut via Shannon (April 1956 only), Paris and Rome. In Beirut, the trip connected with Flight 6 from London with a stop in Frankfurt. From Beirut Flight 6 continued to Karachi, Rangoon, Bangkok, Hong Kong and Tokyo, where the equipment was changed to a Boeing 377 StratoClipper. The flight then continued to Wake Island (for fuel) and Honolulu before terminating in San Francisco.”

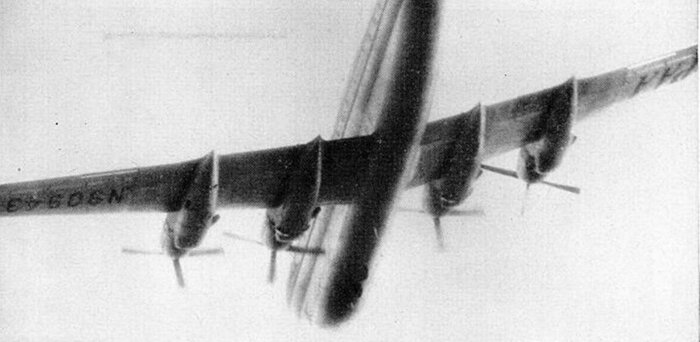

Pan American World Airways’ Boeing 377 StratoClipper Sovereign of the Skies (Serial Number 15959, US Registered as N90943) in magnificent flight over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge in the 1950s. Not long after this photograph was taken, she met her end in the sea halfway between Hawaii and San Francisco on 16 October 1956. The StratoClipper (Stratocruiser in Boeing parlance) was a large long-range airliner developed from the C-97 Stratofreighter military transport, a derivative of the B-29 Superfortress. The Stratocruiser’s first flight was on 8 July 1947. Its design was advanced for its day; its innovative features included two passenger decks and a pressurized cabin, a relatively new feature on transport aircraft. It could carry up to 100 passengers on the main deck plus 14 in the lower deck lounge; typical seating was for 63 or 84 passengers or 28 berthed and five seated passengers. N90943 Sovereign of the Skies had a Boeing production serial of 15959—the aircraft just before serial number 15960 on the Boeing assembly line. Air frame 15960 became Clipper Romance of the Skies, and, flying as Pan Am Flight 7 was lost the following year in exactly the same waters near Ocean Station November as did Sovereign of the Skies. Photo: Pan American World Airways

It was on the final Boeing 377 StratoClipper leg of Flight 6’s circumnavigation, from Honolulu to San Francisco, that the Hollywoodesque drama of Flight 6 (often and incorrectly called Flight 943) unfolded. Pan Am’s StratoClipper N90943 Sovereign of the Skies had begun her portion (the longest) of the journey eastward in Tokyo, a city bustling with energy and industry following the devastating fire bombings and national trauma of a decade before. Sovereign of the Skies had nearly 20,000 flying hours on her airframe. One of her engines had 1,300 hrs after the last full overhaul and another just 300. From Tokyo, with a fresh crew, she sailed majestically into the sun, bound for Honolulu, Hawaii with a fuel stop at Wake Island. The distance to Wake Island was 3,200 kilometres (2,000 miles) and from Wake to Honolulu was 3,700 kilometres (2,300 miles)—a substantial bit of flying and navigation. In Honolulu, after her long and exhausting flight over water, Sovereign of the Skies exchanged crews after almost 18 flying hours since taking off from Tokyo. The fresh crew would be responsible for getting Sovereign of the Skies and her passengers safely to her final stop in San Francisco, some 3,800 kilometres (2,400 miles) across empty Pacific Ocean.

The Flight 6 relief crew, like many Pan Am StratoClipper crews, was the best of the best—Captain, First and Second Officers, Engineer, Purser and two Stewardesses—and all experienced and highly-trained and aware of their primary duties—the safety and the comfort of the passengers in their charge. The crew’s Captain was 43-year-old Richard N. Ogg of Saratoga, New York, a Pan American World Airways company man if there ever was one. Ogg, a pilot for 20 years, had been employed by Pan Am for 15 years, flying for the airline during the Second World War. He had accumulated over 13,000 flying hours in that time and was considered a very capable and calm aircraft Captain. He had 738 hours on Boeing 377s and had recently completed a ditching emergency procedures course.

His First Officer was 40-year-old George L. Haaker, a Pan Am employee since 1946 with 7,500 flying hours, almost half of them in Boeing 377s. He too had just completed a course on ditching. The Flight Engineer was Frank Garcia Jr, a 30-year-old in his third year with Pan Am with 1,738 flying hours, all on the Boeing 377. The Navigator was always a pilot working his way up to the left seat and sometimes called the Second Officer. In this crew he was Richard L. Brown, a 31-year-old working for Pan Am for less than a year. He qualified on Stratocruisers just eight months previously and had 1,283 flying hours with 466 hours on type.

The cabin crew was considerably younger than the cockpit crew, something that was common in 1956 when it was considered a young woman’s job. The cabin crew lead was Purser Patricia Reynolds, aged 30. Despite her young age, she had been working for Pan Am for ten years and had, just three months before, completed a United States Coast Guard (USCG) Wet Drill in San Francisco. She oversaw two highly capable young women—Stewardess Mary Ellen “Len” Daniel, aged 24, who had also just completed the USCG Wet Drill course and Stewardess Katherine Araki, aged 23 of Honolulu, an employee of Pan Am for a year and a half.

While the Boeing 377 was a reliable aircraft and her crew well-trained and committed, she was about to cross 2,400 trackless miles of open Pacific Ocean, with the setting sun behind and a starlit night revealing itself ahead. If her passengers or pilots cared to look out into the inky blackness during the flight, they might see the sparkling lights of an infrequent cargo ship but little more. To help her in her crossing would be the sentinel assurance of Ocean Station November, a United States Coast Guard cutter holding station approximately halfway between Hawaii and San Francisco. The duty cutter this night was USCGC Pontchartrain, a 1,350 ton, 250 foot Owasco-class “high endurance” cutter, built ten years before. An Ocean Station vessel like Pontchartrain had a number of duties including weather reporting, radio relay and most importantly this night, rendering assistance to the growing number of airliners plying the Northern Pacific skies. There was an archipelago of ten Ocean Stations in the Atlantic Ocean and another three in the Pacific, all of which were stationed under well used aerial highways across the oceans. Ocean Station November was, for all pilots, a human voice to report to on every Hawaii to San Francisco flight, but this night Pontchartrain was more than that. She would become a beacon of hope and a link to salvation for 24 passengers and seven crew members.

USCGC Pontchartrain in the all-white paint and gun configuration of the 1950s when she was involved with the salvation of Pan Am Flight 6. Pontchartrain was an Owasco Class (sometimes referred to as a Lake Class as all the cutters in this class were named after lakes in the United States) high-endurance cutter built for Second World War service with the United States Coast Guard. The ship was commissioned just days before the end of the war and thus did not see combat action until the Vietnam War. Pontchartrain was built by the Coast Guard yard at Curtis Bay, Maryland, one of only two Owasco class vessels not to be built by Western Pipe & Steel. Named after Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana, the ship was commissioned as a patrol gunboat with ID number WPG-70 on 28 July 1945. She was used for law enforcement, ocean station, and search and rescue operations in the Pacific and Atlantic. At the time of the ditching, Pontchartrain was acting as Ocean Station November, one of a series of ships holding station in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, forwarding weather information and standing by for such rescues as she carried out with Flight 6. Photo: United States Coast Guard

Related Stories

Click on image

Sovereign of the Skies had landed shortly after 6 PM Hawaii time, and instantly, Pan Am mechanics, cleaners and “rampies” swarmed over her, readying her for the final leg across to San Francisco, which completed her round-the-world flight. At Ogg’s request, her 6,400 gallon tanks were topped up with enough fuel for a 12 hour and 18 minute flight. The outgoing crew greeted Captain Ogg’s crew in Flight Operations and exchanged pleasantries and information about N90943’s flight from Tokyo. The mechanics were busy changing up the mixture control unit on Number Four engine. The Hawaii dispatcher, Denis Sutherland, briefed Ogg and his flight crew on the excellent weather ahead and outlined the approved flight plan. Ogg and Haaker were to climb to 13,000 feet as they headed towards San Francisco and, close to Ocean Station November, they would then climb to 21,000 feet for the second half of the flight.

While Ogg and his crew briefed and prepared for the flight, Purser Reynolds oversaw the loading of food and drinks and made sure the cabin was perfect. Meanwhile the new passengers went through customs and waited in the main passenger lounge. Purser Reynolds welcomed the nine new passengers (one passenger, a Mr. Man Ow from China, had elected to take the next flight that night in order to resolve some customs issues.) In all she would have 24 paying souls in her care—a mixture of tourists, diplomats, military servicemen and businessmen with connections to Asia and the Pacific Rim. There were 13 from the United States, four from the Philippines, three from Japan, one each from Holland, France, Formosa and Indonesia. There were three children. The 15 passengers who had flown in on Sovereign of the Skies from Tokyo were tired and anxious to keep on schedule so as to make connecting flights in California.

The passengers were not the only living souls making the crossing to San Francisco. Pan Am cargo staff cared for and then loaded two dogs, one very talkative parakeet and 3,000 twittering canaries into the cavernous forward hold.

An exciting scene of the Honolulu International Airport from the 1950s. Four Boeing Stratocruisers grace the ramp—Left to right: Pan Am (N1024V), Northwest, United and another Pan Am Clipper. Photo: Aviation.Hawaii.gov

It is clear from period photos that the Boeing 377 Statocruiser dominated Honolulu-based international airline travel. Obvious in both of these images is the heavy moisture in the skies behind the aircraft. Photo: Via Ian Lind at ilind.net

The flight was scheduled to leave Honolulu at 7:30 PM Hawaii-Aleutian Standard Time (HAST), 15 October 1956, but delays in preparations and maintenance issues pushed the time back a full hour. At 7:30 PM, boarding had still not been announced and passengers were getting a little impatient. At 8:00 PM, the terminal public address system boomed out the call for the boarding of Pan Am Flight 6, and passengers collected their belongings and queued at the door. Unlike today’s soulless jet-way bridges, Sovereign of the Skies’ passengers walked calmly across the balmy ramp with a view of the beautiful and powerful aircraft that they were about to board. As they queued at the air-stairs, they were greeted in style by the two young and very beautiful stewardesses. Stewardess Katherine Araki ushered the 11 Tourist Class passengers to their seats in the forward compartment while Len Daniel brought her 13 First Class passengers to the back of the aircraft and settled them in, offering them drinks. In the days of the prop-liner, First Class compartments were not in the front of the aircraft as they are now. For the comfort of higher-paying passengers, it was better to be behind the engines where noise and vibration were considerably reduced.

While the passengers were loading, Flight Engineer Garcia stepped down the stairs and began his walk-around inspection of the aircraft and its engines. Following this, he re-boarded and began his pre-flight checks. He gave Ogg the Ready to Start Engines Report and soon Ogg, Haaker and Garcia had all four Pratt and Whitney R4360 engines thundering and ready to go. Pushing the throttles forward, Ogg moved the big liner away from the ground crew who waved goodbye. With his right hand on the throttles, Ogg used his left on a small wheel near his left knee to steer the lumbering giant out to the runway.

This is likely the scene that welcomed the passengers and crew of Flight 6 on the evening of 15 October 1956—heavy cloud with low angle sunlight, blowing palm trees and the beauty of a Pan American World Airways StratoClipper. Clipper Glory of the Skies (N90942) was the aircraft before Sovereign of the Skies on the Boeing assembly line. N90942 was eventually sold to American Overseas Airlines, then to Aero Spacelines where she was to be converted to a Boeing 377 Guppy oversize cargo carrier. She was damaged beyond repair at Mohave in 1967 during a ground incident with another Stratocruiser. Photo: Via tumblr

At approximately 8:30 PM HAST, Captain Ogg pushed the throttles forward to give 2,700 RPM on each engine, released the brakes, accelerated down the runway and climbed into the late evening sky. Ahead lay a planned 8 hour and 54 minute flight to San Francisco. With all four massive engines spouting blue flame from the exhausts, the Sovereign of the Skies lifted over Mamala Bay, retracted her heavy gear into her wells and set a course for Ocean Station November.

For the next four and a half hours, Sovereign of the Skies maintained an altitude of 13,000 feet on a course of 062 degrees. After levelling off, the night soon enveloped the Sovereign of the Skies. The passengers settled down while the “Stews” prepared for dinner. A period of heavy turbulence ensued, and dinner was delayed. Following dinner, which the turbulence had ruined for some, the passengers stretched out across empty seats and the lights were dimmed for the night.

Haaker flew for the first two hours and was relieved by Ogg. Two hours later Ogg handed over the controls to his First Officer. Though Ogg was a traditional Captain of the period, there was great respect for his First Officer who had four times more flying time in the Boeing 377, even though he had only half the total hours of Ogg.

Garcia kept watch on the engines, Second Officer Brown monitored the radios and updated his course and the two pilots settled down to provide the greatest comfort and stability for their passengers. From time to time Ogg checked the maps and spoke with Brown.

A couple of minutes after 1:00 AM Honolulu time, as she neared the Equal Time Point (The ETP is the location at which going from it, then to either the departure or destination takes the same amount of time), Clipper Sovereign of the Skies radioed Honolulu for permission to climb VFR to their next assigned altitude of 21,000 feet. Four minutes later they had the OK and Haaker pulled gently back on the yoke and began the climb. Below them farther to the north, anyone on the deck of Pontchartrain, if he was looking, might have seen their distant navigation lights on the flat horizon to the south.

Twelve minutes later, Haaker gently pushed the yoke to level his charge off at 21,000 feet and then let her accelerate to 188 knots. Ogg was with Brown at the map table. Everything was fine. The crew remained vigilant. The passengers slept, some in their “sleeperette” berths. The animals in the hold continued to stress.

One minute later, at 1:20 AM, their world started to unravel. There suddenly came a loud, shrieking noise from the left side of the aircraft and the port wing dipped suddenly. In the galley, Len Daniels, who was fixing coffee and Coca Cola for the two pilots, staggered from the lurch and reached out to steady herself.

Haaker called out to Garcia for more power to increase airspeed. As he calmly gained control of the situation, Ogg returned and took his seat. The tachometer for No. 1 engine was rapidly increasing and both pilots immediately diagnosed the problem as runaway propeller, sometimes called an overspeed. It was not an uncommon problem with the Boeing Stratocruiser. The overspeed was caused by the failure of the Constant Speed Unit (governor) which adjusted the pitch of the blades to keep the engine speed constant. When an overspeed condition occurs following the failure of the CSU, the propeller begins to rotate faster than the desired RPM setting—hence the red-lining engine tachometer on No. 1.

The pilot must immediately feather (rotate) the blades so that they are in line with the slipstream. Haaker immediately assessed the overspeed and attempted to feather the blades, but the blades did not respond. Now the prop was free-wheeling in the slipstream and overspeeding the engine slewing the aircraft to the right. The noise was deafening and Ogg and Haaker shouted over the shrieking. While the three working engines were steady at 2,300 RPM, No. 1 was off the dial which only went to 2,900 RPM.

An overspeed propeller was a real concern for an airliner out over the ocean. This photo of a Boeing B-29, from which the Stratocruiser was developed, shows the damage suffered when No. 3 engine’s Constant Speed Unit failed and the runaway propeller could not be feathered. The propeller tore from the shaft and flew into the fuselage, where we can see the damage caused by two blade strokes. Other photos of this ship show that some of the propeller exited up through the left side of the fuselage. To say they were lucky to get to Iwo Jima for an emergency landing is an understatement. Photo: USAF via 7thFighter.com

Ogg and Haaker shouted to Garcia behind them to “Freeze it, freeze it!” Garcia hit a switch which would cut off the oil supply to the troubled engine and force it to stop. It would take a few minutes before the engine would seize, and Ogg asked Purser Reynolds, who had entered the cockpit to see what was happening, to go back into the cabin and watch for fire in No. 1. Two minutes later, there was a decrease in RPM on No. 1, followed by a heavy thud. The engine seized, but the propeller had decoupled from the drive and was now wind-milling out of control on the shaft. The drag caused by the propeller was slowing the Stratocruiser down and Garcia increased power on the three remaining engines to keep speed.

Ogg then made an announcement over the intercom: “Ladies and gentlemen, I’m sorry to wake you, but we have a real emergency. One of our engines is giving us some difficulty. Just in case we have to ditch the plane, please put on your life jackets, take your seats and fasten your seatbelts.” He then informed the cabin crew to prepare the passengers for a nighttime open-ocean ditching and radioed a distress call to Pontchartrain, informing them that he may have to ditch. He got a steer from Brown and turned towards their salvation. Quick calculations of remaining fuel and the reduced airspeed necessary to control a Stratocruiser with a wind-milling propeller indicated that the aircraft could stay aloft for another 750 miles. Both Honolulu and San Francisco were over 1,000 miles away however. It would be Pontchartrain or nothing.

The problem was that it was pitch dark and even though Pontchartrain was firing off star shells and was laying down a string of electric water lights in the best direction for ditching, a nighttime water landing would likely result in tragedy. If he could maintain altitude and nothing else went wrong, Ogg calculated he could wait out the night and ditch after the sun came up. At 2:00 AM HAST Ogg told his crew and that of Commander William Earle, Captain of Pontchartrain, that he would fly circuits over the ship until first light, which was three hours away. Pontchartrain left the water lights on the surface of the ocean should the situation change.

The crew and passengers settled down in an atmosphere of calm stress to wait out what most surely would have been the longest four hours of their lives. The aircraft droned through the night, keeping the lights of Pontchartrain and the water runway in sight. At around 2:15 AM HAST, Ogg and Earle were calmly discussing options and Plan Bs, when Earle informed the Pan Am captain that the aircraft carrier USS Bennington was speeding to the scene. “Maybe you can land on the carrier” he quipped. Ogg laughed and declined. The atmosphere was both professional and warm between the two men.

A blurry photograph, taken by travelling Navy Seabee Albert Spear, shows weary and worried parents Jane and Richard Gordon holding their sleeping twin daughters Maureen and Elizabeth during the long and stressful hours as the StratoClipper circled Pontchartrain. Photo: Albert Spear via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

A photo taken sometime during the early hours of the morning, as the StratoClipper flew in circles above Pontchartrain and passenger Hiroshi Shiga stands to stretch his legs wearing his life jacket. In the aisle at the staircase leading to the upper compartment, Pan American Airways navigator and Second Officer Richard Brown looks the epitome of calm as he chats with passengers. These remarkable images taken at time of great stress reveal the strength and resiliency of both passengers and crew. Photo: Albert Spear via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Ogg’s situation got considerably worse at 2:45 AM. No. 4 engine began to backfire and instruments indicated a big drop in power. Garcia analyzed the situation and found that the electrical system was shorting and the second radial row of cylinders was not firing properly. Ogg then instructed Garcia to feather the No. 4 engine and the Engineer reached up and hit the controls and successfully feathered the propeller blades.

The engineer then reset the remaining two engines to deliver 2,550 RPM and the engines began a 2,000 gallon-an-hour fuel burn rate. The speed had dropped to 140 knots and the aircraft was down to 2,000 feet, possibly too low if they were not set correctly for the ditching in their circuit above Pontchartrain.

At 3:00 AM, Ogg took the aircraft back up to 5,000 feet as it has become lighter with the fuel burn. At this height, the cockpit crew practiced approaches and drill, readying for the dawn. It was Ogg’s plan to burn off as much fuel as possible to reduce the possibility of a post-ditching fire and to make his aircraft as buoyant as possible. Then night wore on and the worrying consumed the passenger cabin.

At 5:10 AM the stewardesses moved the First Class passengers forward as far as possible, filling the seats in Tourist Class. Captain Ogg had ordered this as the previous year another Pan Am Stratocruiser, Clipper United States (N1032V) had been forced to ditch just 35 miles off the Oregon Coast following the complete loss of No. 3 engine and its propeller. Loss of control forced the ditching during which the tail section broke off after slamming into the waves, resulting in four deaths.

Just the year before, Pan American World Airways Clipper United States (N1032V-above) with a runaway propeller that resulted in the loss of No. 3 engine was forced to ditch 35 miles off the Oregon coast. In that instance the tail and rear fuselage tore off on impact and four people were lost. Photo via ThisDayInAviation.com

Ogg continued to burn off fuel, while down on the ocean’s surface, Pontchartrain was pulling the electric lights from the water and Earle asked Ogg for a ten-minute warning of the ditching so that his crew could lay down a half mile-long path using fire-fighting foam to mark the best course for ditching. The foam would also allow Ogg and Haaker to better judge their height over the water at the last moments and might help reduce the possibility of a surface fire. At 5:40 AM, Ogg called Pontchartrain and notified them that he would be ditching in half an hour.

A photograph taken by Dutch passenger Hendrick Braat from the cabin of the Sovereign of the Skies shows Pontchartrain about to lay down a “runway” of foam on the otherwise calm surface of the Pacific Ocean. Photo Hendrick Braat via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Coast Guard sailors aboard the Unites States Coast Guard Cutter (USCGC) Pontchartrain use foam from firehoses to lay down a “runway” for Captain Ogg and Flight 6. In addition to giving him something to aim for, the foam allowed him to judge his height better and would help in the event of a surface fire. Photo: William Simpson, USCG via Google Books and LIFE magazine

As the crew of Pontchartrain scrambled to dump barrels of pre-positioned fire-fighting foam from the fantail as well as from firehoses at the rail, Ogg dropped the aircraft to 900 feet and made a practice approach to the foam runway, overflying Pontchartrain in the process. In the passenger cabin everyone was instructed to take their crash positions. Ogg made an announcement to the passengers: “Ladies and Gentlemen the water temperature is 74 degrees and the waves are only a matter of inches high. There is absolutely nothing to worry about-things couldn’t be better for us. I’ll soon give you a ten-minute warning. Then one minute before touchdown I’ll tell you this is it. Do as the stewardesses tell you please.”

With the sun just up, Captain Ogg in N90943 thunders low overhead Pontchartrain before setting up for a dangerous ditching. No. 1 engine (port outer) is still wind-milling, while his Number 4 engine (starboard outer) is shut down and its propeller clearly feathered. This dramatic image somehow expresses the stress and fear felt by all those inside her cabin and cockpit. Moments later, Ogg would set up for the ditching, announcing just prior to hitting the water that “This is it!” Photo: William Simpson, USCG via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

At 6:05 AM, Garcia released carbon dioxide into the wing tanks to deal with any fire and everyone got set for the ditching. Captain Ogg pressed the microphone button and told his passengers: “Ten minutes to ditching time.” Eight minutes later, Ogg turned the fatally injured Sovereign of the Skies to a heading of 315 degrees one last time and set full flaps. He began a long, flat and slow approach to the foam runway with Haaker on his controls in case needed. At this moment, Brown left his cockpit seat and, rushing past the bent-over passengers, some of whom were praying, took his place by the main door, where he was to assist the rapid and orderly evacuation of the Stratocruiser when she came to a stop. At the same time, Ogg announced: “This is it!”

A rather poor and slightly retouched enlargement of a photograph of Ogg’s approach to a water landing—flaps down, gear up, starboard propeller feathered and not visible. The photographer was Pontchartrain’s cook by the name of William Simpson. Photo: William Simpson, USCG via Wikipedia

With Pontchartrain standing off with her boats half-lowered, Ogg and Haaker skimmed Sovereign of the Skies low over the swells, cut power to his two remaining engines and settled to the surface at a speed of 90 mph. She lightly touched at first, skimming a few hundred yards on ground effect before slamming down hard into the swell. For a few seconds it looked like a textbook water landing, but the wounded port wing caught the swell, bit hard into it and the giant aircraft slewed violently to port, turning nearly 180 degrees.

Flight 6 slams into a swell and chunks of the two powered propellers (2 and 3) fly off. In 2009, when pilot Chesley Sullenberger did exactly the same thing, there were not the same quality of images of the event itself, despite Smart phones and closed circuit TV in New York’s harbour. The nose-high impact would break off the aircraft’s tail, but the crew was ready for this eventuality and had all passengers over or forward of the wings. Photo: William Simpson, USCG via Wikipedia

With water mist still settling, the aircraft slews around to the left as Pontchartrain steams towards them. Photo: William Simpson, USCG

The impact cracked the gleaming white fuselage just ahead of the massive tail—just as it had with Clipper United States the year before. With a shrieking rending of metal, the entire tail toppled slowly backwards. If it were not for Ogg’s insistence that everyone move forward, it is likely that a few passengers would have followed the tail to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Moments later, as passengers could be seen to scramble out onto the wings, the tail disappeared altogether.

Pan Am Flight 6 comes to a complete stop about half a mile from Pontchartrain with her tail now broken off and about to sink. Inside, stewardesses and crew are taking up predesignated positions at the doors and passengers are just unbuckling their seat belts and getting ready to get into life rafts. Photo: William Simpson, USCG

Commander Earle, standing off to stay out of Ogg’s way, now ordered full steam ahead as Pontchartrain raced to close the distance to the remains of Sovereign of the Skies and to rescue as many passengers as she could. Suffice it to say that the crew, the passengers and rescuers from Pontchartrain executed everything to perfection. I won’t go into the details of what happened in the interior or how the rescue was carried out. The following photographs, most published in LIFE magazine the following week, tell the story better than I can.

An illustration from LIFE magazine, October of 1956, depicts the metrics of the ditching. Illustration by Randolph E. Brotman via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

As Pontchartrain approaches, passengers on both sides of the aircraft clamber into inflated life rafts, as the cutter’s crew drop whaleboats into the sea for the rescue. This image is eerily reminiscent of Sullenberger’s Airbus in the Hudson River. Photo: William Simpson, USCG

A photo taken from the deck of Pontchartrain shows passengers in two of the airliner’s three launched inflatable life rafts. The raft released from the starboard side would become snagged in the wreckage of the broken-away tail. Photo: William Simpson, USCG

In a photograph taken by Captain Nick Bountis from the cockpit of his Transocean Airlines aircraft orbiting the scene, USCGC Pontchartrain steams up to the now tail-less Boeing StratoClipper with her boats suspended halfway in their davits ready to be lowered. We can just make out the life raft at the back of the broken fuselage on the starboard side. The foam “runway” can be seen at upper right. Photo: Captain Apostolis “Nick” Bountis via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Pontchartrain moves in closer as one of her whaleboats hurries to help passengers with a small inflatable raft across her gunwales. Stunned passengers seem to be staring into the open cavity where the Stratocruiser’s tail had once been. Other Coast Guardsmen were to keep a sharp eye out for sharks. Moments later, Coast Guardsman Ronald Christian would leap from his boat and enter the shattered fuselage of Sovereign of the Skies to check that everyone had escaped. He needn’t have worried, as Ogg made sure he was the last person off. But Christian showed great courage entering the sinking wreckage. Five minutes after he left, the fuselage sunk. Photo: William Simpson, USCG

Passengers in one life raft that was tangled in the wreckage transfer to another by stepping onto and crossing the port wing. Photo: Hendrick Braat via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

With the port outer engine (the one that started all the trouble) in the foreground, passengers clamber over the wing to the forward side to get into another raft. Photo: Hendrick Braat via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Grateful passengers pack the whaleboats of Pontchartrain. Under a bright morning sun on a bright blue sea, they all have been granted a second chance at life. Photo Marcel Touzé via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

French Army doctor Marcel Touzé sits in one of Pontchartrain’s boats with Mrs Rebecca Jacobe and her 3-year-old daughter Joan. The stress can be seen on their faces, but one can also read the sense that they have been given a new life. That spectacularly sunny day on the Pacific will live on in their memories until their dying days. Photo: Hendrick Braat via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

The last to leave the sinking aircraft was Captain Ogg, having just checked to make sure that no one was left in the passenger cabin. Similarly, 50 years later, Captain Chesley Sullenberger, who was 5 years old at the time of the Pan Am ditching, would do exactly the same thing. In this photograph taken by passenger Braat, he seems hardly stressed at all, smiling almost. No doubt the realization that all of his passengers and fellow crew members not only survived, but did so without a scratch, gave him much comfort at this moment. Photo: Hendrick Braat via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

With the abandoned life raft snagged in the wreckage, StratoClipper N90943 pitches down and begins to sink. Just twenty-one minutes after the ditching, she sank out of sight and began one last long and dark journey to the bottom of the ocean, where she rests today. Photo: Captain Dr. Marcel Touzé via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Three wonderful photos from the reunion in San Francisco. At left, Richard Ogg, the hero of Flight 6, kisses his wife Blanche. In the middle photo, Coast Guardsman Ron Christian, who entered the wrecked Stratocruiser before she sank to look for survivors, is embraced by his fiancée Lois Cloud. At right, three of the true heroes of the ditching—the Stewardesses (as they were known then)—leave Pontchartrain. They are Purser Pat Reynolds (left), Katherine Araki and Mary Ellen “Len” Daniels. In those days, while the “Stews” were all beautiful young women, they were highly-trained and dedicated to their first responsibility, the safety of their passengers. Photos: Left: Robert Lackenbach, Centre and right: Bill Young via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

With their ordeal behind them, Richard and Jane Gordon hold their daughters close as they are about to stand on solid ground for the first time in three days. Photo: N.R. Farbman via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

Nothing depicts the relief felt by passengers and their families than this photograph of passenger Ruby Dami being swept off her feet by her husband Ray, after which he ran with her for about 200 feet into the pier building at San Francisco before he let her back down. Photo: Lonnie Wilson via Google Books and LIFE magazine, October 1956

One of the passengers, on climbing aboard Pontchartrain, exclaimed “Thank God for the Navy!” It is interesting to note that this type of statement was common and irritated the Coast Guard. Eight years later, President Kennedy gave designer Raymond Loewy (designer of such things as the Studebaker Avanti, the Greyhound Scenic Cruiser, and the Air Force One paint scheme) the contract to distinctively identify Coast Guard ships and assets. That is how the now-ubiquitous diagonal stripe on Coast Guard ships and aircraft came to be. In any event the passengers were safely transferred to Pontchartrain and the two captains enjoyed each other’s company for the next three days as they shaped course for San Francisco.

I was unable to determine which USCG cutter took the place of Pontchartrain on Ocean Station November, but there is no doubt that one did. A day out of San Francisco, a cutter met Pontchartrain and transferred clean clothes for the rescued passengers and crew. In a Coast Guard film about Flight 6 (very poor but gripping amateur footage of the ditching itself), Ogg can be seen with Earle on the flying bridge wearing a Hawaiian shirt. When Pontchartrain tied up at San Francisco’s Coast Guard pier, there were hundreds of press people, well wishers and family members there to meet them.

Sovereign of the Skies sank at 6:35 AM HAST, a little over five hours after the Constant Speed Unit failed on her No. 1 engine. Through five hours of interminable stress, Richard Ogg kept his cool, as did his whole crew. Their professional behaviour, flying skills and calm demeanour went a long way to keeping the passengers safe. Captain Richard Ogg, like Sullenberger 50 years later, was rightly a hero. He would be asked to speak about it for the rest of his life. He remained a Pan Am pilot to the end of his career.

Richard Ogg, who was still actively flying, died at the age of 77 on 4 June, 1991. Six months later Pan American World Airlines ceased operations and filed for bankruptcy. There is no doubt that the demise of the great company would have saddened him greatly. On his deathbed, his wife Blanche saw him with a distant and sad look in his eyes. She asked him what he was thinking about. “I was thinking of those poor canaries that drowned in the hold when I had to ditch the plane.” Ogg replied.

They don’t make ’em like that anymore.

Dave O’Malley