ON BEING THREE

I sat there - in the Harvard cockpit, exhausted but satisfied after shutting down on the grass. Not a soul in sight, just me and the sounds of gyros winding down, metal clinking and clanking with different rates of contraction as it cooled. Surrounded by the smell of hot oil, sweat-stained leather and new mown hay (after lying all day in the scorching sun), the same birds that built nests in my engine cowl squawked in the forest behind the hangar. A great time for quiet reflection as the sun cast even longer shadows. I am content at the moment. Funny how life is a collection of moments. How did I get here? Not the GPS part, but which path did I follow to end up as Number 3 on an aerobatic team?

Twenty-five plus years have passed since I performed my first formation aerobatic air show. I believed that it could be safely done and set out to prove my theory by hanging off my dad’s right wing. After a few years of his coaching, I was able to accomplish things that he had learned through trial & error during a lifetime. It was now time to make my own mistakes. We didn’t know if it could be done, but tried anyways. Tiny advances in lessons learned were major successes to us. He had little time to spare, and I, just a young’n, had no money. Somehow we managed for years until I also had too little spare time. Our last performance turned out to be London, Ontario. My mother happened to see it and I gave her a ride home in the back seat in the formation. She saw her husband leading and her only son flying wing on the quick hop back to Woodstock, Ontario. We didn’t know it then, but we would never fly like that again.

Dad lost his medical that summer. It was revoked by the government late in the season. Many years of challenges have only lightened his wallet. Now, it was too late. Absolutely nothing escapes time, including dad’s health.

I am middle-aged now, and another young’n (Dave Hewitt) had dabbled in formation aerobatics off dad’s wing while I was chasing a career. I knew more about what he was thinking than even he did. We sucked in (read recruited) a good friend (Pete Spence) who was now flying formation with us, but not aerobatics. All three of us had mutual respect for one another on and off the ground. I had fun doing some of Pete’s initial Harvard training, so I knew he would be excellent.

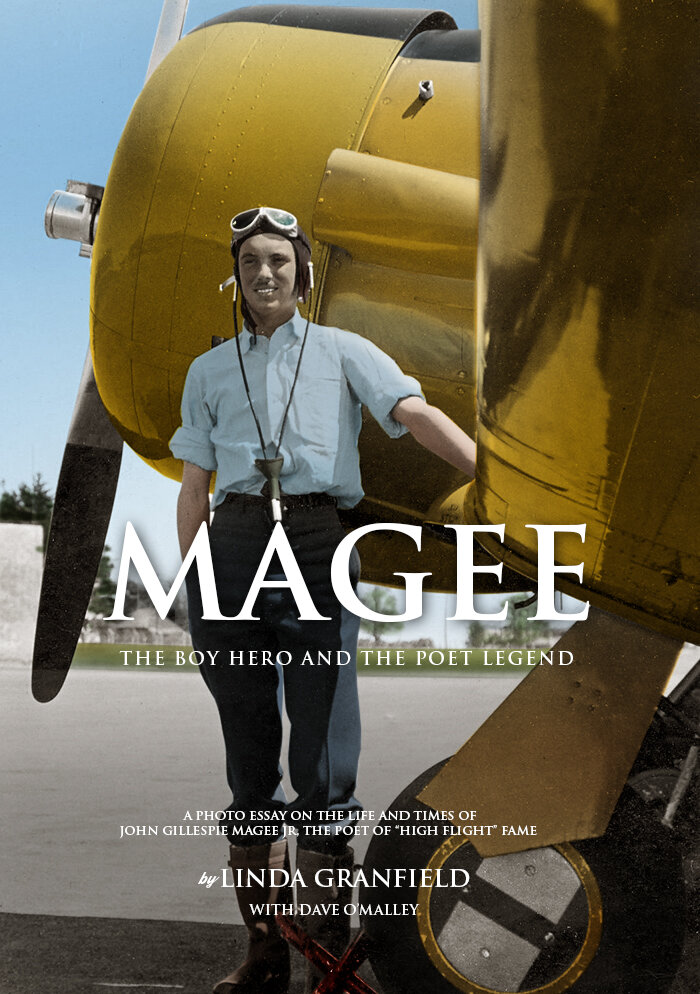

When we were 2. Father, mentor, friend, Norm Beckham poses with his son Kent on the set of Iron Eagle II, a Hollywood aviation fantasy film for which they flew their "Americanized" Harvards. [Now I finally know what the N in N. Kent Beckham stands for - Ed] Photo via Kent Beckham

Norm and son Kent lay down a trail of smoke together when they flew aerobatic formations as a two-ship. Photo via Kent Beckham

Now there is three. N. Kent Beckham in Harvard 53 sticks like glue to Dave Hewitt in the No.2 position in the Echelon Left formation. This photo shows us just how close they get and how perfect their show can be. Photo: Camera Clicker, Ron Dowdellca

Related Stories

Click on image

We were one airplane short, but details didn’t stop us. The summer of ’99 saw me training both Dave and Pete to lead and fly right wing or “2”. Eventually we hammered out a deal with the Canadian Harvard Aircraft Association and were able to use one of their Harvards as lead ship under numerous conditions. Time and money were in short supply and we all figured that I had the best chance of figuring out how to fly the number 3 position. Once again the school of hard knocks would be my teacher. Dave had more experience at formation aeros than Pete, but under our tutelage the gap had been eliminated. Pete, a heavy equipment operator by profession, has a very smooth and precise feel for an airplane. He had more overall flying experience than Dave. So it was that Pete, Dave & Kent became 1, 2, & 3 respectively. Eventually Pete acquired his own mount and the level of maintenance increased. We were now flying for more than just ourselves – we had existing fans and new audiences to win over. Our first show was of all places – London – picking up exactly where I had left off.

The three pilots of the Canadian Harvard Aerobatic Team - L-R Dave Hewitt (No.2), Peter Spence (Lead) and N. Kent Beckham (No. 3). All three pilots are valuable partners of Vintage Wings of Canada, sharing their considerable knowledge of Harvard operations and formation flying. Photo: Dave Blais

Being 3 is like an aerial game of three dimensional ‘crack the whip.’ If Pete is having an off day, Dave has a very bad day, and I’m so far out of the picture that the formation just ends. World War II trainers do not have the power to correct for mistakes of this magnitude. Eventually I taught myself how to cheat, like sneaking slightly to the inside of a loop to travel less distance in the same time. I still can’t think of a way to cheat on the Trail Roll so I have Pete cheat for me. By adjusting the lead ship’s power throughout the roll I stand a chance. If 2 bobbles – I’m toast! It’s all about teamwork. I have yet to see another team perform this manoeuvre.

I find the Barrel Roll to the left extremely trying, as the team is rolling into me forcing me to reduce power and push the stick left and forward as we roll upside down. Pushing forward on the stick while inverted will cause the carburetor float to cut off all fuel to the engine. I‘m kind of fond of a good running engine. It’s somewhat difficult to stay in formation without one.

Another signature manoeuvre is the formation Half Cuban in which we all change from echelon right to left while rolling from an inverted 45 degree down line. It’s not easy and has claimed the lives of those before us. One year at the Canadian International Air Show in Toronto, an evaluator/ friend asked us to consider dropping it during the preflight walkthrough just before the performance. Try getting your mind into the “zone” after that for an over water performance!

Our flying skills have been honed razor sharp. We have flown these cantankerous tail draggers at shows with winds that toppled outhouses with seven cinder blocks on the floor trying to hold them upright. (If you must know – the floor is higher than the seat.)

What’s next? Find out at our next air show. After flying, the next best thing is talking about it to someone who appreciates it. Eugene Loj and Greg Tyrell do our commentary and are approachable with beer. If we’re in the air, try dad. In my case, he has made all the difference.

The members of the Canadian Harvard Aerobatic Team perform the Vic Loop together on a clear day. Photo: Dani Cela

One gets the desire to shout "Tora Tora Tora" when looking at this fabulous image of Peter leading Dave leading Kent at the Red Bull Air Races in Detroit this past summer. Photo: Tom Podolec

Nearly 70 years after its first flight, the Harvard still thrills a crowd. Kent, Pete and Dave rip up the futuristic waterfront of Detroit this past summer at the Red Bull Air Races. Photo: Tom Podolec

When he's not in his CHAT uniform, or his airline uniform, Beckham can sometimes be seen in his Vintage Wings get-up at the controls of our Supermarine Spitfire - a dream of Kent's since he was a boy. Photo: Peter Handley