FLYING WITH THE PROFESSOR

For the past six years, we have been immersed in a sea of stories of Canada's greatest aviators – the bomber, fighter, transport and training pilots, crews and maintainers of the Second World War. They represent all that is great about the world of aviation and Canada in particular – professionalism, creativity, sacrifice, achievement, and passion for flight. We hold them up as exemplars of the greatest values we aspire to – dignity, kindness, duty, honour and sacrifice. They lead us today, nearly seventy years after they wrote history across the skies both here in Canada and overseas.

Surrounded by the golden glow of Canada's heroic aviators, I sometimes fail to realize that Canada still produces some of the finest aviation professionals anywhere on the planet. Recently, it dawned on me that, though they have not taken their Spitfires or Mustangs into harm's way (save Paul Kissmann and Steve Will and their CF-18 squadrons), survived the decimation of their squadrons, nor struck down enemies in mortal combat, the pilots and maintainers of Vintage Wings of Canada are the absolute equals of any aviators anywhere, in any era, or in the employ of any cause. It's a case of not seeing the forest for the trees.

While all of our pilots and maintainers are family, some don't live at home. We've got some of the world's finest aircraft restorers in Comox, British Columbia, working on the Roseland Spitfire IX project and a new scion of our family in the Maritimes, from which will grow our Eastern wings. And then we have our Vintage Wings West cowboys. Before I get into the story of an adventure recently taken with their support and welcome, I need to call them out.

Led by the lady-magnetized and uber-competent Todd Lemieux, the Vintage Wings West boys are, pound for pound, the most passionate about aviation and the most dynamic ambassadors for our enterprise. Lemieux, an oil patch businessman and warbird pilot, has imbued his cadre with the historical timbre and emotional energy needed to carry out our mission unflaggingly during long summer weekends, signing up members, researching history, telling stories of our great aviators and sharing the flight experience with all comers. Lemieux has brought together a group of the finest aviators in God's Country to support his outreach in Western Canada. There is Dave Maric, the always grinning, wide-eyed, open-hearted Westjet First Officer who never tires and brings a youthful enthusiasm to the task. There is Gord Simmons, a Westjet Captain and a man who is “all in”. Whether it's flying the Stearman or Cornell, loading passengers, telling stories, hefting trash bags or joining in on a hell-bent-for-leather, knock-down and drag-out pub crawl, the eager “Gordo” is a keystone participant. There is the lanky and enigmatic Liam O'Connell, a high-time tail-dragging oil patch consultant who once ran the Red Deer, Alberta Airport. Quiet and soft spoken, his demeanour belies a passionate aviator... with nice hair. Towering over them all is Ron “Lurch” DuJohn, an air force brat turned aviator. Ron's experience steps on every rung of the professional pilot ladder – cadets, powered flight, light tail-dragger bush flying, Arctic flying with Kenn Borek and then on to a captaincy with Westjet.

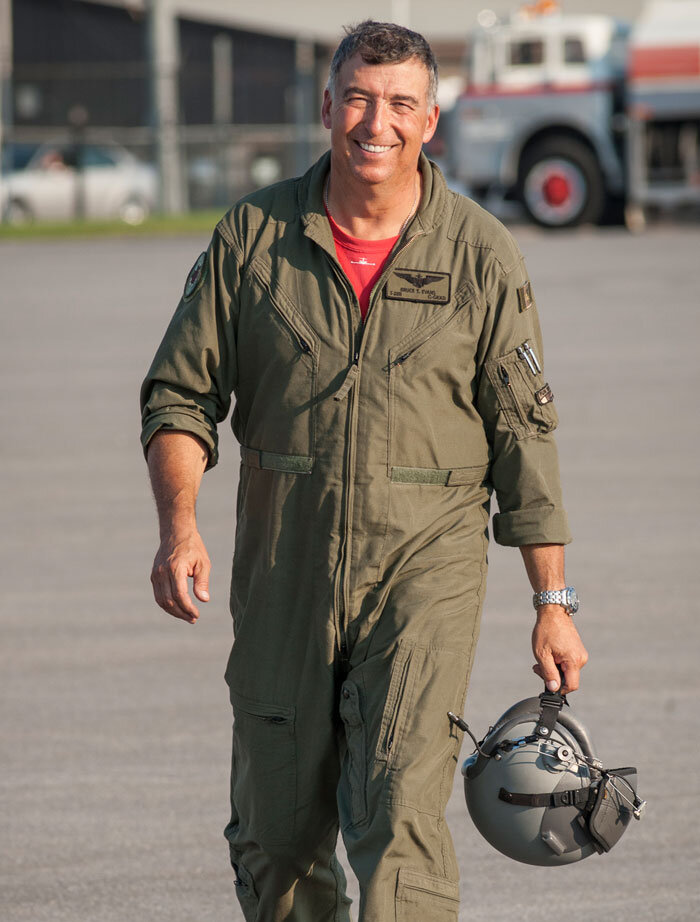

Then there is Bruce Evans.

Always smiling, the soft spoken warbird aviator is a pilot's pilot... always honing his craft, always willing to share his experience and his beloved T-28 Trojan. Photo: Peter Handley

The son of an RCAF maintenance engineer and private pilot father, Evans has avgas in his bloodstream and wings in his DNA. His countenance is best described as beatific – kindly in a competent sort of way, direct, welcoming, magnetic, soft-spoken with a constant knowing look that borders on blissful. Evans is a pilot's pilot, engaged in one of the world's most expensive and demanding hobbies – warbird operation and flying. Like his comrade, Gord Simmons, Evans is “all in”.

After much deliberation while searching for a Harvard to buy into the warbird world, he ended up buying a T-28 in 2008 and he flies it everywhere from British Columbia to Québec and even Florida to learn more, fly more and see more. For him, the T-28 is not a hangar-bound show piece, but rather a living, breathing warbird, meant to be flown for more than simply his own personal pleasure.

Evans is a geologist by training. Educated at Queens University, where he commuted from his home town in North Bay by airplane, Evans has earned his rock spurs over decades by tramping through the bush in nearly every province and many foreign countries on several continents. With boots on the ground and armed with a rock hammer, inclinometer, a bottle of hydrochloric acid and a can of bug spray, Bruce has paid his dues and seen first-hand the importance of mining in Canada. While engaged in mineral exploration in Sierra Leone, Evans, through necessity, got involved in aerial geophysical survey. Before he knew it, he had a company named Firefly Aviation, engaged in aerial survey work in Africa, Europe and the Americas. Evans has spent years sitting in the back of his own aircraft, manning the magnetic anomaly detection equipment, while one of his pilots kept a steady course and AGL altitude through some pretty rough terrain and even rougher turbulence. If you want some serious anti-vertigo training for your future aerobatic flying, there is no better way than stuffing yourself into the hot, gassy ass-end of a Navaho over rolling, super-heated equatorial Africa with your eyes glued to an oscilloscope for hours at a time.

Related Stories

Click on image

A good portrait of Evans at the controls of his T-28 as he warms her up prior to departure for another flight a couple of days after our adventure. For great video of Bruce Evans sharing the “aero” experience with Vintage Wings volunteer Alan Shafto click here. Photo: Peter Handley

THE OFFER

Back in May, during the second annual Canadian Air Demonstration Formation Camp, held at Vintage Wings of Canada, Evans offered me the opportunity to ride shotgun with him in his T-28 on his way back to Calgary. Like the workaholic with a maladjusted life focus that I am, I turned him down due to my presumed inflexible workload. The world is crowded with miserable old men like me who could have, would have, or should have. The moment I turned Bruce's offer down, I felt defeated and remorseful. Of course, I have had lots of great aviation adventures in my life, more than most. One thing I should have learned from these adventures and their attendant lifelong memories is that every invitation should always, no mater how difficult the workload is, be accepted, embraced, and finally lived. Well, I surmised... I had let this great adventure pass me by.

But Bruce Evans would not forget and, three weeks before the Wings over Gatineau en vol Air Show, he made the offer one more time by phone – this time eastbound out of Calgary for the show in Gatineau. If I thought my workload was heavy in May, three weeks before the show, the weight of work was Jovian in its gravitational pull, anchoring me to my desk with a plus 20 branding G-load.

Despite the due dates, this time, it would be different. I accepted, telling Bruce, “I'm in.” Minutes later I bought a one way ticket to Calgary. You only live once as they say, and I needed a new memory to put away and open when I am 85.

To some, it might be just another Westjet flight direct to Calgary, but to me it was carrying me up and away from the funk I was in, towards the setting sun and adventure. Photo: Dave O'Malley

I needed this. It seemed that it had been weeks, even months that I had been working non-stop on Vintage Wings website development, web stories, brand creation, posters, ads, certificates, aircraft markings, calendars, media events, T-shirt designs, retail store concepts, signage, banners, power-points, and the endless flow of communications and branding tools required for the astounding achievement that is Vintage Wings of Canada. And then there was my day job.

Sometimes, just sometimes, it begins to feel like too much for me – the steady piling of tasks, the endless phone calls, the flurries of emails, scheduled meetings, the last minute tasks, and the “I-thought-I-told-you-about-thats”. What is normally a joy, becomes just one deadline, one more task, followed by another and another. The stress builds like a growing electrical current, amping-up, physical in its presentation, and invisible to everyone else. It becomes increasingly more difficult to determine whether it emanates from your head or your heart. Soon you notice that you sleep only four hours each night – in one hour fits – that you are going through the ibuprofen like gummy bears, that you stop off at the liquor store on the way home and that your dreams are exactly like your working day.

Like I said, I needed this.

It would only be two and a half days... work would wait. As it turned out, it was one of the best flights I have ever taken. The following two days would be a 2,000 mile, low level, cross-Canada tour of the head frames, open pit-mines, settling ponds, exploration sites and geological formations between Calgary and Gatineau. From Bruce Evans, I would learn more about Canadian geology and mining history in these few short hours than I had ever been exposed to or absorbed in my life. By the end, I had experienced an amazing thing – a two-day, cross-Canada, crash course in mineral geology from a flying classroom. And Bruce was the Professor Emeritus, and Dean of Warbird U.

In the thoroughly modern Firefly Aviation hangar at Springbank Airport (CYBW), Todd Lemieux (Left) and Bruce Evans prepare the T-28 for the trip to Ottawa. Their casual, easy going attitude belies a professionalism born of many years of flying. Photo: Dave O'Malley

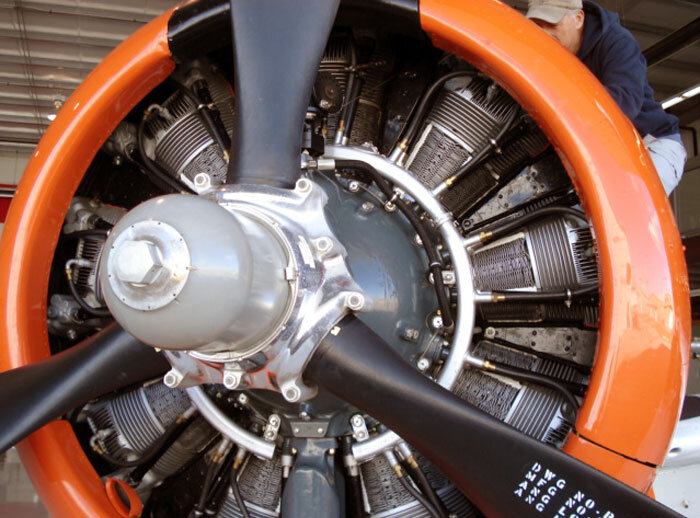

Bruce Evens checks the oil in the big 1,425 hp Wright R-1820-9 radial engine. A foot peg can be extracted from the exhaust shield to allow maintainers to step up to the oil filling access panel. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The Wright R-1820-9 radial engine which powers Bruce Evans' T-28B Trojan would prove to be a steadfast friend throughout the crossing, never once faltering nor indicating strain in any of her myriad gauges. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Being in the Big and Tall category, Todd Lemieux had to do a little surgical adjustments with my parachute. Photo: Dave O'Malley

After we rolled the Trojan out to the ramp, Bruce checked pressures (60 psi) in all three tires. Had we been recovering on a carrier, it would have been substantially more. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Just before launch, I take a moment to allow Todd Lemieux to capture my excitement... but in a casual, devil-may-care sort of manner. Photo: Todd Lemieux

Todd “Pepe” Lemieux walks out to the wing tip to take a photo of us before we depart. Only in Calgary would it be deemed OK to walk on the wing of a warbird in cowboy boots. Photo: Dave O'Malley

And this is what Todd took at that very moment. Dave strapped in tight, yet Bruce is relaxing. Photo: Todd Lemieux

Todd “Pepe” Lemieux, a.k.a. “Farmboy”, points to Evans and signals engine start. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Bruce Evans warms up the Trojan on the ramp outside the Firefly Aviation hangar. Photo: Todd Lemieux

Across Canada, Bruce would patiently answer my endless questions – “Just what the hell is potash?”, “How is it mined?”, “How do they know where to dig for gold?”, “Are there any places that still remain unexplored?”, “How do they mine under a lake?”, “Why aren't there any cottages on Lake Diefenbaker?”, “What makes that island a good place to dig, but not that island over there just two kilometers away?”, “What happens to all those tailings man?”

I learned about eroded volcanic pipes, deep-origin volcanoes and the importance of minerals such as ferrite, syenite, pyroxinite, apatite, biotite and pyroxene, which are found beneath the Manitou Islands and Callander Bay of Lake Nipissing. I learned that they were mined laterally from shore. I learned about thousand-kilometer fault lines that crease the endless and wild expanses of Northern Ontario. I began to think of Evans as the "Professor” as he gently and enthusiastically dispensed bits of his vast knowledge of Canadian geology and mining operations... most of it learned from personal experience hiking the rugged ridges, river valleys and lake shores below.

Flying at 11,500 feet from Calgary to Regina we discussed terrain, geology, mineral extraction and Evans' own history. The wide expanse of prairie grasslands and isolated communities flew by beneath as we raced along with a tail wind that drove a 205 knot cruising airplane over the ground at nearly 270 knots. Flying the beautiful T-28 Trojan was a blast, though in ferry mode, certainly not taxing. Follow the pink line on the GPS, watch your altitude and ask questions. Early in the flight, most of my flying was done with my eyes flicking constantly over the altimeter as I porpoised plus or minus 300 feet eastward to Regina. Evans was kind enough to give me the stick for much of each leg and I learned to relax and spend more time looking around at the world's most beautiful country. We made refueling stops in Regina, Winnipeg (overnight), Thunder Bay and Sudbury and did, in just a few hours, what took days in the Stearman earlier this year.

When I first accepted Bruce's invitation to make the transit, I told him how grateful I was for the opportunity. His answer was 100% Bruce Evans – he said: “The best thing about owning a warbird is sharing one.” He did more than just share his beautiful airplane with me. He shared his knowledge, his time, his adventurous spirit and his constant search for perfection as a pilot.

I won't go into much of this incredible flight, for it is a thing you must experience viscerally on your own, in an airplane, in the company of a great aviator like Evans. But I will say that, if you ever get the opportunity to do a similar thing or to participate in any adventure, leap at the chance, no matter the cost or the pressures in the workplace. As Jimmy Buffett once said... “If you ever wonder why you ride the carrousel, You do it for the stories you can tell.”

Dave O'Malley

Somewhere over the Alberta prairie, I take a self-portrait as we climb to 11,500 feet en route to Regina, Saskatchewan. The particular T-28B Trojan owned by Evans has a green sun-shade at the top of the canopy. This makes it very comfortable inside the cockpit on sunny days and casts a very dramatic green light throughout the cockpit. Life suddenly was a whole lot better. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Flying east out of Alberta we find ourselves over Southern Saskatchewan, where we come upon the long westernmost tendril of Lake Diefenbaker to our right. This part of the lake is more like a river and cuts eastward for almost two hundred kilometers. Seeing geography from this perspective is one of the finest attributes of flight. Photo: Dave O'Malley

We cut across Lake Diefenbaker. Moose Jaw lies now to the southeast about 85 kilometers away. One of the largest geographical features on the Saskatchewan prairie is Lake Diefenbaker, named for a Saskatchewan firebrand politician and Canada's 13th Prime Minister, John George Diefenbaker. Lake Diefenbaker, a reservoir and bifurcation lake, was formed by the construction of Gardiner Dam and the Qu'Appelle River Dam across the South Saskatchewan and Qu'Appelle Rivers respectively. Construction began in 1959 and the lake was filled in 1967. The lake is 225 kilometres long with approximately 800 kilometers of shoreline. Lake Diefenbaker provides water for domestic irrigation and town water supplies. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Somewhere over South Saskatchewan, we got a kick in the pants from a strong tailwind. Normally cruising at 205 knots, the Trojan was scorching along at over 260 knots ground speed (300 mph) in cruise at one point. Here, just a tad east of Lake Diefenbaker, we are 98 miles from Winnipeg, steaming along at 249 kph (287 mph). Photo: Dave O'Malley

Coming into Regina, Evans asks for and is granted the left overhead break. The break is a military tradition designed to bring an echelon formation of two or more aircraft down the active runway at say 300 feet. Then the break is called and the first aircraft pulls a hard high-bank turn to bleed off speed and curve through base leg to downwind for the landing. Each successive aircraft would then break at predetermined intervals of one to four seconds. This creates separation between aircraft as they roll onto final for landing. When a single aircraft asks the tower for the break, it is either for practice or for show or both. In this shot, we can see the 80 degree bank. Great fun! Photo: Dave O'Malley

Evans pumps 100 Low Lead into the wing tanks at Regina. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The 60 knot tailwind grin. Perfect flying conditions will bring a smile to any aviator's face. Zooming into Bruce's rear view mirror, I catch a glimpse of his ever present smile even wider than normal. Photo: Dave O'Malley

At the end of a long day, Professor Evans takes control and lines up the runway at Winnipeg, foregoing the overhead break at the busy airport. The sweeping visibility offered by the T-28 is clearly evident on the image. Photo Dave O'Malley

In Winnipeg, we fuelled up and left the Trojan for the night. Time for steak, beers and more geology lessons. Photo: Dave O'Malley

In the grey light of morning, the plains city of Winnipeg passes beneath us as we turn to the east. Ahead, at 7,500 feet lay a heavy cloud layer mixed with forest fire smoke which stretched to the east as far as Kenora. To get to the open weather and better visibility we churned eastward though some frisky weather. While strapped to your passenger seat in the long humanity-filled tube of an airliner, this experience might be uncomfortable, but belted tightly to the seat of the T-28, this was simply joyful fun banging our way to Thunder Bay. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Early on the morning of the second day, we leave Winnipeg on a choppy morning in a murk made of glowering cloud and forest fire smoke. We can smell the fire in the cockpit. Here, we overfly the endless lakes, bays and channels of the rugged Kenora and Lake of the Woods Region which straddles the Manitoba-Ontario border. Looking down on the watery landscape, I think about the emergency vests, out of reach in the baggage compartment. Bruce assures me that the T-28 can make any land visible in the triangle described by the line from the nose to the wingtip to the fuselage. Of course, all that land is covered by heavy forests and ancient rock formations, but he also assures me that the rugged airplane could take on any of Canada's boreal forests. Photo: Dave O'Malley

On the left side, the lakes and bays are nearly obscured by a heavy haze. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The “Professor” conducts his classes from the front of his T-28, while his student throws question after question at him from the back seat – a far better student-teacher ratio than I was used to in university where classes of three hundred students listened to a prof drone far below in a theatre of mediocrity. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The massive gaping maw of Barrick's Williams Open Pit Gold Mine at Hemlo, Ontario is an old stomping ground for Professor Evans. The mine, about 40 kilometers east of Marathon, Ontario, output an astonishing 227,000 ounces (more than seven tons) of gold in 2011. As we made a couple of turns overhead the three separate mines at the remote Northern Ontario location, he filled me in on the history of the operation and his experiences down on the ground during the wild and wooly early days of exploration. Gold was discovered in the Hemlo area in 1869 but it wasn't until the 1940s that trappers, prospectors, geologists and investors staked claims covering some newly discovered occurrences that, later on, turned out to be the claims from where gold would be extracted in modern times by the Hemlo mines. The object in the bottom of the photo is not a UFO, but rather part of the canopy defrost system. Photo: Dave O'Malley

In the break overhead Sudbury Airport. Photo: Dave O'Malley

One of the best feelings you get during a long cross-country flight is the feeling of releasing your ass from hell when you shut down. Strapped down as tightly as you can endure on a hard parachute pack, you are unable to even lift a butt cheek for more than two hours. Unstrapping makes your tush very happy. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Beautiful airplanes attract beautiful women... it's a law of the universe. Here Sudbury FBO operator Christine Romansky checks out the T-28. Christine runs the Northern Aviation Services Shell FBO at the airport. Photo Dave O'Malley

By the time we reached Sudbury, Ontario, Kilo Kilo Delta was starting to get a little road dirt down her sides. Photo: Dave O'Malley

File this under “I never knew that!” A satellite shot of Lake Nipissing reveals the remains of two “deep-origin” volcanoes. The island archipelago on the middle of the lake, known as the Manitou Islands and the circular bay at the eastern end of the lake, known as Callander Bay were formed by eruptions from farther below the earth's surface than ordinary volcanoes. These bring near the surface some of the rarest minerals known to man... thus sating the world's appetite for apatite!

At the end of a long and glorious day of geological education from Winnipeg to the Ottawa Valley, Evans taxies the Trojan home to our Gatineau hangar with the long shadows of the late afternoon silhouetting the “Professor” on the port wing of his warbird. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The end of a great adventure... though my butt was happy, my heart longed for it to continue. Thank you Bruce.