HONOURING A MODEST MAN

Each country in the world has its own first flight, its own J.A.D. McCurdy. While the Wright Brothers may have been the first to successfully fly a powered heavier-than-air craft, others around the world were not far behind. In New Zealand, Richard Pearse was right behind them. In Europe it was Santos-Dumont. In Canada, the honour fell to a 22-year-old graduate engineer in a distant corner of the Dominion. John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, known as Douglas to his friends and family, would pilot a broad-winged contraption of his own design and called the Silver Dart for its silvery coloured fabric surfaces. McCurdy was not a risk-taking showman in the manner of many earlier aviators. He had a youthful confidence in his rigorous skills as an engineer and in the new science that he and his associates of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) were helping to establish. The AEA was a small group of talented engineers, tinkerers and thinkers who were drawn to the Cape Breton home of legendary Scottish-born inventor and visionary Alexander Graham Bell. Bell had surrounded himself with the talented and energetic young men of the AEA and tasked them each to design, build and fly an aircraft of their own design. The Silver Dart was McCurdy’s design, and with it, he cemented his place in Canadian and aviation history.

McCurdy’s grandson, Gerald Haddon, has long loved and admired his grandfather and today travels the country to raise the profile of this Canadian icon. This summer, Haddon and his wife Amanda travelled to his childhood haunts to pay homage to a man of great accomplishment and abiding modesty. — Ed

An Important Unveiling

Amanda and I set off from Oakville, Ontario to drive the 2,000 kilometres to Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia where the Bras d’Or waters beckoned us with a sparkling welcome.

Lorna MacDonald, Professor of Voice Studies at the University of Toronto, is the Creator and Librettist of “The Bells of Baddeck”, a Music-Drama that tells the story of Alexander and Mabel Bell and how the small hamlet of Baddeck on Cape Breton Island captured their hearts. Lorna had invited us to come to Nova Scotia where the month-long production was taking place from 2 July to 2 August 2016, at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site. I had been asked to participate in several of the pre-performance “Bell Chats” and to deliver speeches. This remarkable and inspiring production captures the spirit of Alexander Graham Bell, one of the world’s most beloved inventors, and I was honoured to have been afforded the opportunity to expand on the life of my grandfather John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, who was one of “Bell’s boys”.

Born on 2 August 1886 and brought up in Baddeck, young Douglas McCurdy could often be found at Bell’s magnificent summer home known as Beinn Bhreagh helping him with his glider and kite experiments. When not assisting Bell, McCurdy would often be playing with his daughters Elsie and Daisy Bell. My grandfather remained lifelong friends with the two women and was a frequent visitor to Beinn Bhreagh even into his seventies. During his childhood, McCurdy met many famous scientists and inventors who were drawn to this small hamlet of 100 people because of Dr. Bell’s worldwide reputation for innovation. Having lost two sons in infancy, Bell wanted to adopt my grandfather when he was five years old, so strong was the bond that had developed between the two of them. Had it not been for his strong-minded and motherly maiden Aunt Georgina McCurdy, he would undoubtedly have become the Bell’s legal son. “J.A.D. McCurdy was born a McCurdy, and by God, he will die a McCurdy,” she firmly stated. However, Bell did become a godfather to my grandfather and in 1893, Dr. and Mrs. Bell took my grandfather, age seven, to Washington, D.C. where he spent a very happy year as part of their family. Later on, recognizing my grandfather to be a brilliant student, Dr. Bell helped sponsor his education to St. Andrew’s College in Aurora, Ontario and encouraged my grandfather to attend the University of Toronto’s School of Mechanical Engineering, where he was the youngest student to be admitted to the program.

Aerial view of Beinn Bhreagh (pronounced “ban vreeah” and meaning “Beautiful Mountain” in Scottish Gaelic), the 1,600-acre country estate and 37-room mansion of Alexander and Mabel Bell at Baddeck, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Bell and his wife came across the Bras d’Or Lakes while on a vacation cruise north to Newfoundland and fell in love with it, the place, with its landform and local Scottish culture, reminding them so much of Bell’s native Scotland. From 1888 to Bell’s death in 1922, they would spend much of their time here. Photo via brasdorpreservation.ca

At the outset, Beinn Bhreagh was largely a summer home for the Bells, but in his later years, Bell and Mabel would live there year-round. Being far from busy urban centres, the estate relied heavily on its own vegetable gardens. Here, kitchen staff are seen selecting produce for their table in 1910. Photo via cbisland.com

Bell’s estate was blessed with the steady and constant winds of a Maritime Province. Alexander Graham Bell (left) observes the performance of a kite of his design on the grounds of Beinn Bhreagh, Baddeck, Nova Scotia. In the background is one of Bell’s grandsons, Melville Grosvenor (the future president of the National Geographic Society and editor of The National Geographic Magazine) is doing what boys everywhere will do, running after a kite. Between 1895 and 1910, Bell experimented with many strange kite forms, from circular to tubular to tetrahedral; kites that would look like advanced NASA experiments even today. This circular kite is made from tetrahedral cells joined with two fabric-covered discs. For a look at Bell’s stunning work with kites, click here. Photo: Pinterest

Related Stories

Click on image

My grandparents had a beautiful summer house in Baddeck where I spent many blissful holidays as a young boy. And it was here that “Gampy”, as I called him, taught me how to sail. Navigating around Bras d’Or Lake as a young boy with his two brothers, he became aware of the power of the wind and what it could do. And from those early days, a lifelong curiosity was born—a curiosity that would lead him to become an extraordinary engineer and gifted pilot with a list of glittering aviation firsts to his credit.

The McCurdy’s relax at Baddeck, Nova Scotia in 1947 on their summer house lawn overlooking the place of his first flight. Left to right: J.A.D. McCurdy, grandson Gerald Haddon, son Robert, wife Margaret, daughter Diana Haddon and with Gerald’s twin sister Donna. Photo via the author

I was asked by Professor MacDonald to give a number of post performance talks at the museum about my grandfather, Honorary Air Commodore, The Honourable J.A.D. McCurdy, Canada’s first pilot who made the first flight in the British Empire on 23 February 1909 in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, as a member of the Aerial Experiment Association, in a fragile aeroplane he designed and built and called the Silver Dart. To be able to give a talk in the Bell Museum under a replica Silver Dart built by a group of volunteers of which I was one was an unforgettable moment. The Aerial Experiment Association was born on 1 October 1907 in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. Members of the group called themselves “Associates” and were five in number: Alexander Graham Bell, J.A.D. McCurdy, Casey Baldwin, Thomas Selfridge, and Glenn Curtis. The Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) was formed with one purpose in mind, “To get a man into the air.” Commenting on the AEA, Dr. Bell said: “We breathed an atmosphere of aviation from morning till night and almost from night to morning … I may say for myself that this Association with these young men proved to be one of the happiest times of my life.”

Members of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA). The AEA came into being when John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (top right) and his friend Frederick W. “Casey” Baldwin (top centre), two recent engineering graduates of the University of Toronto, decided to spend the summer in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. McCurdy had grown up there and his father was the personal secretary of Dr. Bell (left). He was close to the Bell family and was well received in their home. One day, as the three sat with Dr. Bell discussing the problems of aviation, Mabel Bell, Alexander’s wife, suggested they create a formal research group to exploit their collective ideas. Being independently wealthy, she provided a total of US$35,000 (equivalent to $920,000 in 2015) to finance the Association, with $20,000 made available immediately by the sale of property. They were joined later by Glenn Curtiss (lower right) who was recruited for his knowledge of gasoline engines and Thomas Selfridge (lower centre), an American Army officer who was assigned to the AEA by the US Army at Theodore Roosevelt’s behest. Photos via internet

Members of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) pose along with famed American balloonist Augustus Post (right). Each person in this grouping would become, in their own way, aviation pioneers. Left to right: Frederick Walker “Casey” Baldwin became the first Canadian to pilot an airplane—the AEA’s White Wing, which he himself designed and flew at Hammondsport, New York in 1908. Though the first Canadian to fly, his milestone accomplishment unfortunately did not receive the same national acclaim as that of McCurdy who flew the first flight inside Canadian borders. He was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1974 in its first induction ceremony, as was McCurdy. Next to him stands Lieutenant Thomas Etholen Selfridge, a West Point graduate from the same class that gave us Douglas MacArthur. Selfridge designed the first successful powered aircraft of the AEA, known as the Red Wing (for the red fabric of its wings), which was flown by Casey Baldwin in a short flight of about 300 feet. He became the first American military officer to successfully pilot an aircraft solo when he flew White Wing at Hammondsport. He also became the first person to die in a crash of a powered aircraft when he was killed in September of 1908 while flying as a passenger in a Wright Flyer flown by Orville Wright. Selfridge Air Force Base in Michigan is named for him. Next to Selfridge in the dashing hat is Glenn Hammond Curtiss, the soon-to-be-legendary American aviation pioneer and a man widely recognized as the godfather of the U.S. aircraft industry. Curtiss was responsible for designing and piloting the AEA’s third aircraft, nicknamed the June Bug. On Independence Day, 1908, he flew a mile in June Bug, in what is thought to be the first pre-announced public flying demonstration of a powered aircraft in the USA. He was the holder of US Pilot’s License No. 1 (Wilbur Wright was No. 5). Each aircraft of the AEA was powered by an engine designed by Curtiss. He and his company were responsible for many iconic American aircraft such as the Jenny, the P-40 Warhawk and the C-46 Commando. His name still survives in the corporate persona of the aerospace giant Curtiss Wright Corporation. Next to Curtiss stands Bell and then McCurdy, who is on crutches following a motorcycle accident. Finally Augustus Post stands at right. Augustus Post was a pioneer aviator, author, and lecturer on aeronautics. He started ballooning in 1900 and was one of the first heavier-than-air pilots after the Wright brothers. He was a charter member of the Aero Club of America and served as its secretary for twenty years. In 1919, he drew up the regulations for the New York to Paris flight contest that Charles Lindbergh won in 1927. Photo via the author

Contrary to popular belief, the first flight of the Silver Dart in Canada was not its, nor McCurdy’s first flight. McCurdy made the first flight in “his” aircraft in Hammondsport, New York after it was completed at Glenn Curtiss’ shop. The aircraft got its name from the silver rubberized fabric designed for balloons which covered its wings. Behind him the V-8 engine designed by Glenn Curtiss turns over the large hand carved propeller. Note the trousers tied down to help keep out the cold. Photo via the author

At the same wintry week that McCurdy flew his Silver Dart from the frozen surface of Bras d’Or Lake (22–24 February 1909) the AEA also flew Bell’s tetrahedral contraption called Cygnet II, a powered version of his earlier towed kite Cygnet, which flew for the first time in December 1907. It used the very same engine that took McCurdy and the Silver Dart into history on the 23rd of February. Unfortunately, the powered flights met with no success. Photo via carnetdevol.org

In preparation for Canada’s first recorded flight of a powered heavier-than-air craft, the Silver Dart is towed by a one-horse sleigh belonging to John MacDermid onto the frozen surface of Baddeck Bay, helped and guided by eight of Bell’s staff and friends, 23 February 1908. Photo via the author

McCurdy, in stocking cap, is seen at the controls of the Silver Dart minutes before his historic flight. With fuel and McCurdy aboard, the Silver Dart weighed just 860 pounds. Bell had long been recording and photographing his kite experiments and the AEA’s flights, always careful to put the dates on the photos (in some cases the dates were written on signs that were included in the shot, to offer unquestionable proof of the date of the event. Some, who claim that other earlier aviators, such as Richard Pearse and Gustav Whitehead, had bested the Wrights have no such photographic proof to back their claims of a successful flight. Photo via the author

In a decidedly Canadian scene, the Silver Dart is positioned on the ice of Bras d’Or Lake by skaters, with McCurdy at the controls in preparation for making the first flight by a British subject within the British Empire. Photo via the author

In the now-iconic Canadian image, J.A.D. McCurdy makes the First Flight within the British Empire in the Silver Dart, followed by skating Cape Bretoners. Photo via the author

Moments later, McCurdy descends gently to the ice as he passes the photographer. The first flight was approximately half a mile at an altitude between three and nine metres. Photo via the author

On 24 February, assistants position the Silver Dart on the ice on Baddeck Bay, readying it for a second flight. After this picture was taken, McCurdy flew 4.5 miles. After its first tentative flight, McCurdy extended the Silver Dart’s range. On 10 March, he flew the aircraft some 22 miles over a circular course. By August, the AEA knew enough about the Silver Dart and controlling flight to offer ride to a passenger—the first passenger flight in Canada. Photo via the author

Not only did we participate in The Bells of Baddeck productions, but my wife and I also travelled on to Halifax where we were graciously invited by His Honour Brigadier-General the Honourable J.J. Grant, Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, to stay in Government House for the unveiling of a magnificent Portrait Bust of J.A.D. McCurdy, commissioned by the Province of Nova Scotia.

Some sixty years ago, I had, over the course of my grandfather’s tenure as the 20th Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, stayed at Government House a number of times. It is the oldest official state residence in Canada and has been the working residence of the Sovereign’s representative in Nova Scotia for more than 200 years. This beautiful Georgian home and National Historic Site contains an impressive collection of art and antiques that reflect the province’s history and heritage. Their Honours insisted that Amanda and I explore the history and beauty of Government House, adding that we were free to wander throughout the residence. It was wonderful to revisit so many of the magnificent rooms that I had last explored as a young school boy—a treasure trove of fascinating rooms to a curious ten year old. On being called downstairs to meals, I remember the long banister which I would slide down with wild abandon, much to the disapproval of my concerned grandmother but to the great amusement of my grandfather.

I also recall many discussions with my grandfather and the lessons that he passed on to me, as I quietly sat at his feet. He taught me some of the endearing and durable qualities that make Nova Scotians such special people. He was born in Baddeck and never forgot his roots. When Prime Minister Mackenzie King appointed him Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, the press besieged my grandfather for a comment. He said he was privileged and honoured and would perform his duties “as well as a country boy from Cape Breton could.” In spite of the many honours that came his way during his lifetime, he always remained a modest man, who invariably directed the conversation towards others.

As the King’s Representative, McCurdy relished his new position because it provided him the opportunity to serve his beloved province from where so much of his worldwide fame came. In his Vice-Regal position, he met people from every station in life and invariably treated each individual exactly the same. Whatever he accomplished in his post as Lieutenant Governor, it was McCurdy’s talent for maintaining the common touch, in spite of the required dignity of his official position, that endeared him to the thousands who came to know him. To a young boy such as myself, he was a magnificent figure in his official uniform. He truly was my hero.

In 1959, the Queen appointed my grandfather an Honorary Air Commodore in recognition of the 50th Anniversary of his historic flight. The only other person, at that time, sharing the same distinction was Sir Winston Churchill.

J.A.D. McCurdy, in his Montréal apartment in 1959, holding a model of the Silver Dart on the 50th anniversary of his historic flight. In the same year, he was awarded the prestigious McKee Trophy—awarded annually since 1927 to a Canadian citizen who has made an outstanding contribution to the advancement of aviation in this country. McCurdy died two years later. Photo via the author

That same year, in celebration of his flight, The Royal Canadian Air Force appointed J.A.D. McCurdy the very first civilian Honorary Colonel of the RCAF. As fortunate as I am to have been mentored by and been born the grandson of J.A.D. McCurdy, it is a singular honour for me to carry on this tradition in my role as an Honorary Colonel in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Christian Corbet, a Canadian artist of international stature was entrusted with the responsibility of sculpting my grandfather’s work. At the unveiling of the portrait bust, I was breathless at first, vainly searching for words to describe what my eyes were attempting to absorb; the portrait was so lifelike that I felt my grandfather would speak at any moment. Made of a bronzed resin, the sculpture is made of bronze with a light blue colour patina. As Christian explains: “J.A.D. McCurdy spent a lot of time looking to the sky and to the water for his inspiration, so I decided to incorporate the blue hue into the bust.” Canadians are indeed most fortunate to have Christian Corbet create and donate this historic piece and I would like to recognize his dedication and skill as an artist in sculpting this magnificent portrait of a man I knew and loved.

The blue-tinted bronze portrait bust of The Honourable J.A.D. McCurdy, unveiled at a ceremony in Government House, Halifax, Nova Scotia on 5 August 2016. Photo: Michael Creagan

Amanda and Gerald Haddon with the bust of Gerald’s grandfather, J.A.D. McCurdy, at Government House, Halifax, Nova Scotia. One can see the strong facial similarities between McCurdy and his beloved grandson. Photo: Michael Creagan

Amanda and I are also extremely grateful to Their Honours for graciously hosting this remarkable and unique event and for commissioning the sculpture. Government House has now placed the bust of my grandfather in the State Dining Room and, when one enters this resplendent room, the eye is immediately drawn to the McCurdy Portrait Bust. Opposite my grandfather, a beautiful portrait painting of Queen Elizabeth II hangs above the splendid marble fireplace mantle as well as a bust of His Excellency Major-General the Right Honourable Georges Vanier, the 19th Governor General of Canada and the first Canadian to hold that honour.

Leaving Government House, I could not help but recall something Gilbert Grosvenor, the Chairman of the National Geography Society, once wrote about my grandfather. He wrote that he had known Charles Lindbergh, Roald Amundsen, Richard Byrd, Robert Peary, and Ernest Shackleton and then stated, “I regard J.A.D. McCurdy as a man who ranks with the very greatest of these.”

As Georges Vanier put it: “In our march forward in material happiness, let us not neglect the spiritual threads in the weaving of our lives. If Canada is to attain the greatness worthy of it, each of us must say, ‘I ask only to serve.’ ” My grandfather changed forever the world, the country and the province of his time by believing in a dream: a dream of flight and of putting a man into the air. He served his province and his nation with excellence and with pride.

I am deeply honoured to be his grandson and delighted that we paid homage in Government House to the man who many consider to be the Father of Canadian Aviation.

A photo of McCurdy at the controls of a Curtiss biplane in Florida prior to a demonstration flight. By 1910 McCurdy, after a number of demonstration flights across the continent, was skilled enough at piloting an aircraft that he would consider an attempt at the first crossing of the Caribbean from Key West, Florida to Cuba. Of this attempt he said: “Being young and having the spirit of romance and adventure in my soul, to say nothing of the prize involved [$8,000.00], I decided to attempt the flight.” He was successful in getting to Havana, but was never able to get the prize money from the Cuban government. Photo via the author

RCAF Air Marshal Campbell (left) helps J.A.D. McCurdy (centre) and Air Marshal (Ret’d) Wilf Curtis cut the celebration cake with all three men using ceremonial swords. The dinner, held on 23 February 1959, was in celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of Flight in Canada and the British Commonwealth. Campbell was Chief of the Air Staff from 1957 to 1962 and Curtis was at that time the President of the RCAF Association. A lot had happened in the 50 years since the Silver Dart’s first flight. Photo via the author

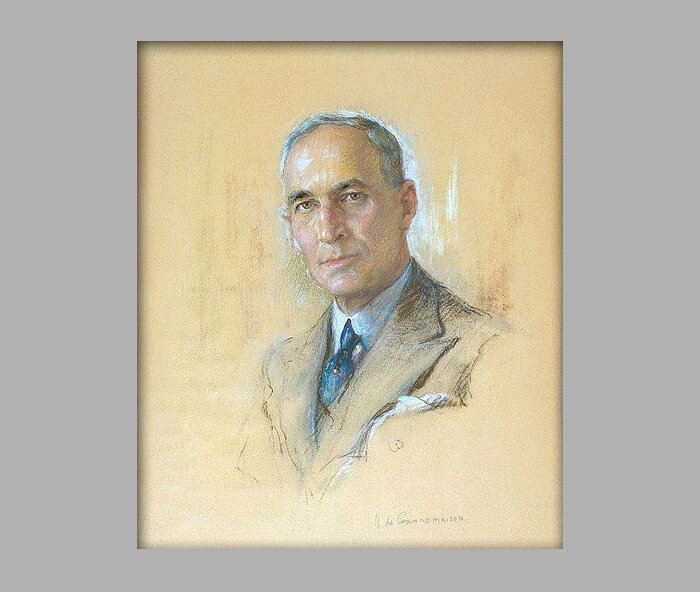

Nicholas de Grandmaison’s magnificent portrait of J.A.D. McCurdy when he was 45 years old. De Grandmaison painted or sketched almost exclusively portraits of Aboriginal people, and rarely of those of other cultural backgrounds. McCurdy’s pastel portrait, completed in 1931, was one of only a small number of his works featuring non-native people. Painting by Nicholas de Grandmaison

100 years to the day and the hour, retired Canadian astronaut, Bjarni Tryggvason, pilots a replica Silver Dart over the frozen surface of Bras d’Or Lake, Baddeck, Nova Scotia to celebrate the Centennial of Flight in Canada. Photos by Janet Trost

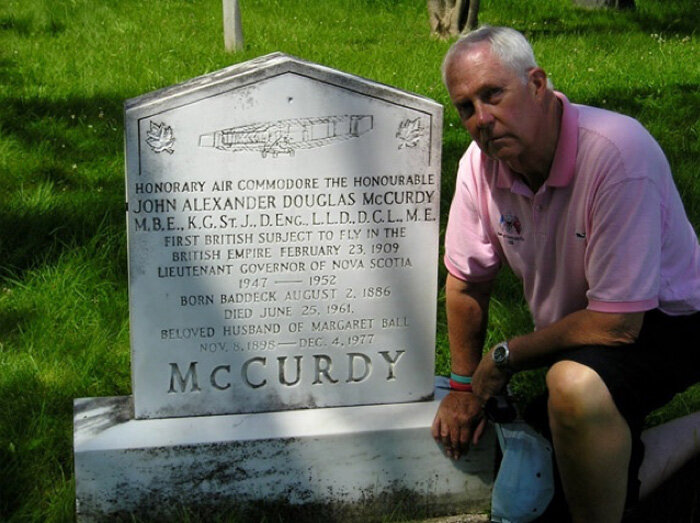

Author Gerald Haddon, kneels beside his grandfather’s grave which faces the expanse of water where McCurdy made his historic flight. Photo taken on 28 July 2009 in Baddeck, Nova Scotia