FLYING IN THE SERVICE OF PEACE

There was a time years ago when the world viewed the armed forces of Canada as keepers of the peace worldwide. Our country was not involved in a combat role in any conflict around the world from the Korean War to the First Gulf War, a span of nearly forty years. Yet our soldiers, sailors and airmen could be found across the globe in areas of recent or ongoing conflict as peace brokers and peace keepers. United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) as a peacekeeping military entity was initially suggested as a concept by Canadian diplomat and future Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson as a means of resolving conflicts between states. He suggested deploying unarmed or lightly armed military personnel from a number of countries, under UN command, to areas where warring parties were in need of a neutral party to observe the peace process. Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his work in establishing UN peacekeeping operations. The United Nations Emergency Force in the Sinai Peninsula, following the Suez Crisis in 1956, was the first official armed peacekeeping operation modeled on Pearson’s ideas.

This is the story of a 23-year-old Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot who volunteered to serve with the UNEF at El Arish, Egypt flying the de Havilland DHC-3 Otter, DHC-4 Caribou, and Douglas C-47 Dakota. It all started in the Officers’ Mess at RCAF Station Winnipeg during a very fateful Friday night TGIF beer call in 1962.

My name is Flying Officer George E. Mayer and I was enjoying my first posting as a staff pilot at Air Navigation School (ANS). I had just graduated from pilot training and a conversion course to the twin-engine Beechcraft 18.

One of the older pilots at the bar (an ancient 26 years old!) stood out from the rest as he was wearing a sand-coloured ribbon. He was obviously too young to be a Second World War veteran but not old enough to have been awarded the Canadian Decoration (CD) for twelve years of military service. I boosted my courage with a second beer, then introduced myself and asked him how he had earned this prominent sand-coloured medal at such a young age.

The young pilot, whose name was Reg, smiled and said, “Buy me a beer and I will tell you all about it.” He began by saying that the ribbon (and accompanying medal) was awarded for serving a one-year tour as a volunteer pilot on loan to the United Nations outpost in El Arish, Egypt. The process, he said, started by writing a memo to his career manager, offering to volunteer for UN service.

As an aside, the competition for good flying positions after a three-year tour at Air Navigation School was fierce, to say the least! ANS had many young pilots who had done their stint as staff pilots and were hungry for better and more operational flying jobs. I knew that I would probably be posted within the coming year and could end up at RCAF Station Nowhere unless I took control of my future!

Here was the chance to control my destiny and do something exciting and rewarding. I thanked Reg profusely and began mentally drafting my memo to Headquarters while I was walking back to the barracks. Only volunteers were accepted and it was with some trepidation that I made the decision to volunteer for service with the UN in the volatile Middle East.

The major benefit from getting this posting was obtaining type ratings on the de Havilland DHC-3 Otter and DHC-4 Caribou aircraft. I had also recently attended the CC-47 (Dakota) course at RCAF Station Trenton, Ontario and had no idea how valuable this course would soon become.

The author as a young Pilot Officer in Her Majesty’s Royal Canadian Air Force wearing regulation summer-weight khaki uniform. Even a Canadian summer uniform would be too much clothing for where he was headed in Egypt. Photo: Author’s Collection

When he arrived at Winnipeg for his tour of duty as a staff pilot at the Air Navigation School, he had just completed a conversion course to the Beech C-45 Expeditor, lovingly known by its pilots and navigators as the Wichita Wiggler or Bug Smasher. George’s role would be to fly the Expeditor around while in the back, student navigators would attempt to get him to the destination and back home again without getting lost. Of course most staff pilots would come to know the area and landmarks well and were not about to be truly lost. Photo via Graham Reeve Collection

One of the older pilots at the bar (an ancient 26 years old!) stood out from the rest as he was wearing a sand-coloured ribbon. He was obviously too young to be a Second World War veteran but not old enough to have been awarded the Canadian Decoration (CD) for twelve years of military service. I boosted my courage with a second beer, then introduced myself and asked him how he had earned this prominent sand-coloured medal at such a young age.

The young pilot, whose name was Reg, smiled and said, “Buy me a beer and I will tell you all about it.” He began by saying that the ribbon (and accompanying medal) was awarded for serving a one-year tour as a volunteer pilot on loan to the United Nations outpost in El Arish, Egypt. The process, he said, started by writing a memo to his career manager, offering to volunteer for UN service.

As an aside, the competition for good flying positions after a three-year tour at Air Navigation School was fierce, to say the least! ANS had many young pilots who had done their stint as staff pilots and were hungry for better and more operational flying jobs. I knew that I would probably be posted within the coming year and could end up at RCAF Station Nowhere unless I took control of my future!

Here was the chance to control my destiny and do something exciting and rewarding. I thanked Reg profusely and began mentally drafting my memo to Headquarters while I was walking back to the barracks. Only volunteers were accepted and it was with some trepidation that I made the decision to volunteer for service with the UN in the volatile Middle East.

The major benefit from getting this posting was obtaining type ratings on the de Havilland DHC-3 Otter and DHC-4 Caribou aircraft. I had also recently attended the CC-47 (Dakota) course at RCAF Station Trenton, Ontario and had no idea how valuable this course would soon become.

Related Stories

Click on image

Following his staff pilot duty at Air Navigation School, George proceeded to get checked out on two of Canada’s most iconic aircraft from the 1950s. The first was the de Havilland DHC-2 Otter, the beefy and highly capable bigger brother of the DHC-2 Beaver. The Otter, in both radial and turboprop forms, remains a hard-working bush aircraft in Alaska and the Canadian North—nearly 70 years after its first flight. Known as the CC-123 in RCAF use, it saw service as a liaison/utility, search and rescue, and light transport aircraft, flying on skis, wheels and floats. Here we see Otter 3743, one of the first four Otters provided by the RCAF to the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) at El Arish, Egypt and to the United Nations Yemen Observation Mission (UNYOM) at Sana’a, Yemen. Photo: Author’s Collection

The Royal Canadian Air Force contributed four DHC-3 Otters (along with DC-3s and Caribous) to the United Nations mission known as UNEF, which were delivered by the Canadian aircraft carrier HMCS Magnificent to Port Said and flown off to El Arish. In this photo we see one of the four taking off Maggie’s flight deck at Port Said. Three more Otters would rotate through later but they would arrive and go home via RCAF CC-119 Flying Box Car or CC-130 Hercules. Photo: RCN

After waiting a couple of months, I began to wonder into which paper shredder my career manager had put my application, when suddenly it happened—my flight commander called me into his office and said with a smile, “So you want to leave Winnipeg and minus 40º C and go to Egypt and endure plus 40º C? Well good luck George—here are your orders!”

What followed was a flurry of activity that included immunization shots, a new passport, selling my car, convincing my parents that I really wanted to go, and familiarizing myself about the UN and the country of Egypt. There was of course the traditional RCAF “mugging-out” party to bid farewell to a departing member which included a rather humorous roasting.

By April of 1963, I was in Trenton beginning my conversion courses to the Otter and Caribou. My course on the mighty Caribou was to start in a few days, followed by the course for the Otter, the epitome of the Canadian bush plane. I was teamed up with another pilot who was doing the same course and was heading to Egypt several weeks before me. Flight Lieutenant Jack Buchner was his name and his wife Jean was due to have a baby on his departure date! He asked me if I would switch dates with him so he could be present for his child’s birth and I agreed without hesitation. This cemented our personal and professional relationship and proved to be most beneficial in an unusual and unsolicited way. In any case, I sought no favours.

The Caribou was an amazing aircraft. This was a 30-passenger short takeoff and landing (STOL) transport with twin 1,450 HP Pratt and Whitney R2000 Twin Wasp engines that could fly at very slow airspeeds and land and take off again on a postage stamp-sized field (just 300 metres long).

The de Havilland Canada DHC-4 Caribou, RCAF serial number 5322, in the markings she wore during the period of her service with the United Nations Emergency Force at El Arish, Egypt. She is seen here, freshly painted, flying over a distinctly Canadian landscape before being ferried to the Middle East. George Mayer flew this particular aircraft along with others that were rotated through. After 5322’s service with the RCAF, she was sold to the Tanzanian Air Force as JW9014. She ended her career in Malta at Hal Far airfield as a fire training hulk, finally being scrapped in the 1990s. Photo: RCAF

I completed the Caribou and Otter courses and embarked on a 12,000-mile journey to my new base in Egypt. On arrival at El Arish mid-June, I received a very warm welcome (40º C!) from all of the staff, was shown to my quarters and introduced to my roommate Abdul the gecko. This tiny resident consumed his weight in house flies every day and we would become good friends very quickly!

The author’s accommodations with 115 Air Transport Unit (ATU) at El Arish, decorated in local bric-a-brac and embellished with moose and elk prints from home. In the window hangs George’s Distinguished Fucking Around Cross (DFAC), awarded for meritorious screwing around—more on that later. Photo: Author’s Collection

The next day, the chief pilot and I drove the 16 kilometres out to the airfield where he briefed me on my schedule for the next 30 days. I was curious about the seven-day blank space after my first week there and was soon sorry I had asked! He briefed me in detail about something called “gyppo gut”—a gastro-intestinal upset which caused you to erupt from both ends and rendered you unfit to fly for about one week. Rumour had it that you could squirt through the eye of a needle at 6 feet.

As an aside, on the way to the airport, we stopped at an unusual monument built on the site where the Egyptians and the Israelis exchanged prisoners after the 1956 Suez Crisis. The Israelis exchanged 5,500 Egyptian prisoners captured during the campaign and 77 others who had been captured in various military operations before the war for just one Israeli pilot shot down in the war plus three soldiers captured before the war. Oddly, this was considered a victory monument by the Egyptians!

In a sandy expanse of desert, the Egyptians built a monument to commemorate a post-Suez Crisis prisoner exchange that brought home 5,500 of their soldiers in exchange for 4 Israelis. Photo: Author’s Collection

With the gyppo gut behind me (pun intended) and resplendent in my khaki tropical shorts and shirt and suede desert boots, UN blue beret and dickie scarf, I began a grueling route check to all the outposts and destinations served by our fleet of marvelous de Havilland aircraft. The nature of our flights was mainly to provide logistical support to the peacekeeping ground troops, to transport these ground troops to destinations like Cairo, Beirut, and Cyprus for up to four days rest and recreation (R & R), and to patrol the Egyptian/Israeli border to observe and report any incursions.

The author, Flying Officer George Mayer, showing off his finest Royal Canadian Air Force tropical kit at El Arish—a blue UN cap atop light weight cotton shirt and shorts. As can be seen here, the heat, humidity and dust made it difficult to turn out for duty in a fully-pressed parade-worthy condition. Photo: Author’s Collection

With his RCAF Otter in the background, the author (right) poses for the public relations photographer as he and a Yugoslavian senior army officer go over flight plans on the hood of the officer’s white United Nations Jeep. Photo: Author’s Collection

The challenge in successfully completing these tasks was compounded by poor weather information and non-existing radio navigation aids, (the invention of GPS came 15 years later). Maps for the Sinai desert had huge areas labelled “relief data incomplete” and there was no information available about the surface conditions of the remote desert landing strips we were operating from, except the wind direction. This valuable “gen” was obtained by observing the small flag on top of our jeep’s antenna, but only if the ground troops had arrived prior to our landing time.

I would never say that any flight I made was boring, but some were made more exciting than others if you chose to take advantage of the moment. One such occasion occurred when I was patrolling the Egypt/Israeli frontier in the DHC-3 Otter. Observing a convoy of UN vehicles snaking along the border, I decided to do a very low, high-speed pass over them (as high as an Otter could do anyway). During my pass directly over the convoy, I heard a metallic “plinking” sound. After checking all the instruments and finding no problems, I remained low (20 feet) and sped off to home base. To make a long story short, I had amputated the top six feet from the communication jeep’s antenna with my propeller and had forced the terrified UN soldiers to scramble under their jeeps for cover. The soldiers, who got their nice white uniforms soiled with sand, oil and grease, included a guest general from the Israeli Defense Forces… oops! My reward for this came during the following Friday beer call when I was awarded the “Distinguished Fucking Around Cross” and given the jeep antenna as a souvenir.

A view of the Egyptian/Israeli frontier from an RCAF aircraft. In the early 1960s, the Egyptian–Israeli border was a bleak and, for many reasons, an inhospitable place to operate. Sometimes, the boredom just had to be broken with some shenanigans. Photo: Author’s Collection

George’s DFAC “gong”, awarded for flying so low that he cut the radio antenna from a UN jeep, which, unbeknownst to him, was carrying an Israeli Defense Forces general officer. Photo: Author’s Collection

Another rare incident happened on a Caribou flight to Beirut with a full load of Arab passengers. At cruising altitude over the Mediterranean Sea, I suddenly became aware of some terribly acrid and horribly smelling smoke. I sent the flight engineer back to the passenger compartment to investigate. He returned holding an expired fire extinguisher, smelling as bad as the no-longer-existing smoke and informed me that a few Arab passengers decided to have tea and light a fire with dried camel dung on the wooden floor and they were not happy when it was extinguished.

One has to wonder which manager at UN Headquarters was smoking pot or chewing khat (the leaves of a local plant that were a mild stimulant) when my Caribou’s cargo destined for Gaza Strip turned out to be a cargo hold half full of rabbit cages and the other half jammed with boxes full of rubber hip waders! When I arrived at the aircraft, the fuselage was so packed floor to roof that I could not gain entry to the cockpit by either the huge rear cargo door or the side crew door. The cargo was eventually delivered and since then, I personally have never heard of anyone in the Gaza Strip getting their feet wet chasing rabbits in the Sinai desert, so they must have been put to good use!

The flights from Gaza to Beirut were generally quiet, since we had to fly 30 miles off the Israeli coast until reaching the Lebanon/Israeli border. Without radio navigation aids and with persistently low ceilings, it was very challenging flying. On one such flight I asked my recently-arrived co-pilot why he kept looking out his window and seemed visibly nervous. He told me to take a look and I did! There was an Israeli Air Force Dassault Mystère fighter hanging on our wing and the pilot was giving us the signal to head towards Tel Aviv. This was not possible, considering I had a full manifest of Arab passengers. I asked the co-pilot to watch the Mystère and tell me what he did. I reached over to the throttle quadrant and surreptitiously and very slowly pulled back on the throttles. Within a few seconds there was a very loud bang like the afterburner of a fighter igniting. My co-pilot reported that the fighter had disappeared straight up, not to be seen again! The silver Mystère could not match the slow speed of my Caribou, had obviously entered a stall and had powered his way out, probably changing his shorts after landing.

The town of El Arish is the largest city on the Sinai Peninsula, situated on the Mediterranean coast some 40 kilometres from the Israeli border. El Arish airport is located about 16 kilometres inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The surrounding desert sand is saturated with sea salt which is very corrosive on aluminum aircraft. Our fleet of Caribous was grounded suddenly when corrosion was found on all the wing flap hinges. The solution was to borrow “511”, a C-47 Dakota (CC-129 in RCAF) from the Canadian communication flight in Marville, France. This single tired aviation legend then did the work of five Caribou transports for five whole weeks and never missed a scheduled trip. [511 was likely KN511 (RCAF 12926) which had served with 435 Squadron in the UK at the end of the war and which served with the RCAF for another thirty years, including at the Air Navigation School in Winnipeg. It still flies today with turboprop engines and is registered with the US Department of State–Ed.] As I was the only pilot legally current on this type, I got to do currency check rides on all the other Dakota pilots and had the fun of returning the aircraft to the RCAF NATO base at Marville.

The old workhorse Douglas C-47 Dakota KN511 (RCAF serial 12926), a veteran of the Second World War was employed by George Mayer and his fellow El Arish-based pilots to do the work of an entire fleet of de Havilland Caribou for more than a month. The top photograph shows “Old 511” in her early postwar RCAF livery in 1949, while the lower photo shows her in 2003 awaiting refurbishment at Middletown, Ohio. Fitted by Basler with turboprops, “Old 511” soldiers on to this day with the United States State Department. Photos: Top: Library and Archives Canada; Bottom: Mike Powney via aerovisuals.com

On a more humorous note, Friday nights (TGIF) at El Arish required one to be dressed in full Arab kit to gain access to the officers’ mess. This particular TGIF night, I dressed in my Yemeni Arab clothes, slipped on my flip-flops, wrapped my Jordanian keffiyeh on securely and headed for the mess. It must be noted that, after almost a year in desert weather, my skin was as dark as any local, and I was blessed with a generous and majestic Arabic nose. I surely resembled a local, especially in the evening light and more so to my pilot colleague guarding the mess entrance who was well over the .08% legal limit himself! He denied me access mistaking me for one of the base employees. I removed my head gear, uttered a few recently-learned expletives in Arabic and, with a laugh and a handshake, managed to gain entrance to the raging party.

My one-year tour at El Arish was interrupted by a six-month tour in Yemen. Very few knew people in Canada or even in the RCAF that there was a 134 Air Transport Unit (ATU) Sana’a, Yemen Peace Keeping Mission (UNYOM) running concurrently with El Arish. The mission was established in 1963. Civil war had broken out in Yemen in 1962 as it tried to separate from Egypt. The United Nations set up the UN Yemen Observation Mission (UNYOM) to ensure that it did not escalate and draw other countries into the conflict. The ATU operated Caribous, Otters and Sikorsky H-19 helicopters. Unfortunately, there was a 65% medical repatriation rate which required several trained, acclimatized pilots to be posted immediately to fill a shortage. My first flight to Yemen turned out to be a six-month posting. Check the UNEF/UNYOM website, read my story of life there and enjoy the many coloured photos of the mission.

Flying and ground life in foreign countries was not all fun and games as this story may, so far, have led you to believe. Our Commanding Officer, Wing Commander Earle Harper, was killed in a tragic night road accident not far from El Arish on the way to Gaza. The Egyptians blocked the road at night with three eight foot lengths of railway track welded together to form a sort of multi-triangle shape which was very hard to see at night. He ran into one and was killed while his passenger, our Supply Officer, was badly injured.

There were a number of close calls on the flying side, but there were no accidents or aircrew lost during my year in the Middle East. However, in 1966, my friend and colleague Flying Officer Paul Picard and twelve ground troops were killed when their Otter crashed after takeoff at an outpost in the Sinai. We were friends and flew together in Winnipeg and he decided to volunteer for the Middle East after we had spoken just before I left ANS.

The flying and living in Yemen for that extended six-month period was even more challenging. There were thunderstorms occasionally exceeding 65,000 feet. Leaving Sana’a, where our headquarters were located, required taking off from the airfield at 7,400 feet above sea level, climbing to at least 13,000 feet to clear the surrounding mountains and even higher in poor visibility. Three of our four outposts were scattered around the desert and one was on the shore of the Red Sea.

Flying in and out of Sana’a and other remote Yemeni airfields had many challenges—gravel runways with obstacles, dust storms and high density altitudes. Photo: Author’s Collection

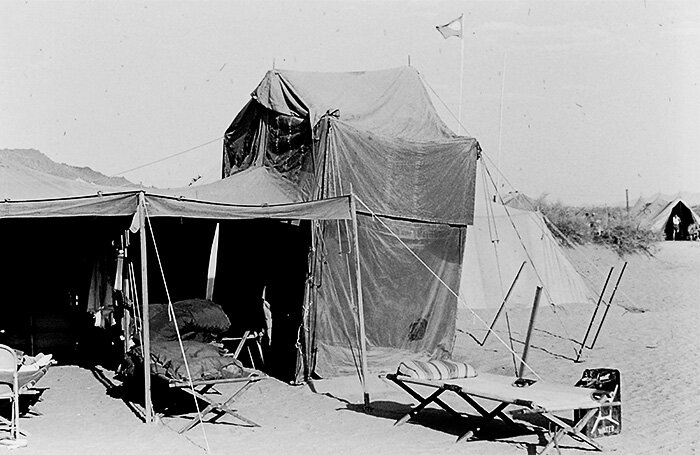

Living in UNEF outposts in Yemen in 1963 was roughing it in the extreme, but the challenges and professionalism of the RCAF crews and pilots made the posting an adventure worthy of many mess tales in the years to come. Photo: Author’s Collection

Conditions in Yemen were particularly gruelling—extreme heat, dust and lack of proper facilities. Maintenance personnel working in these conditions also suffered from the scourge of swarms of flies, requiring the men to wear meshed hoods over their heads as Mayer’s flight engineer, Leading Aircraftman Daniel Vodden had to on this day. Photo: Author’s Collection

In the outposts, I wasn’t happy about having to pay the RCAF C$95.00 a month for room and board when we were living in American tents and eating American field rations supplied free at the outposts. The rule was that single officers were obliged to pay the RCAF for room and board no matter where they were posted.

Living conditions in Yemen were atrocious, which caused the 65% medical repatriation rate. In summary, page 33, para 63, report on the Yemen mission by LCdr Bryan, Directorate of History (DND-1986), contains the following statement by a military doctor: “No human being should ever be subjected to the living conditions experienced by the personnel at 134 ATU Yemen mission.”

Living and working conditions at El Arish, Egypt were also trying and there was no end of complaints from the military residents. However, when personnel from Yemen were sent there occasionally for three or four days of “rest and relaxation”, they thought they were in paradise! Unlike Yemen, in El Arish they enjoyed a clean room, palatably cooked food, potable water, hot showers, movies, a Doctor on base, a small store with attractive items, and a well stocked bar and a nice beach. There were however, very few complaints from the El Arish personnel when there were Yemen folks in residence.

It wasn’t all Hell-on-Earth at El Arish. Though Mayer and the other RCAF contingent at El Arish considered it tough duty, UNEF volunteers who were stationed in Yemen, and were sent there for R and R, thought of El Arish as a sort of paradise. Being close to the blue Mediterranean Sea had its benefits as well. In this photo, some of the locals stroll near the coast. Photo: 115atu.ca

The most important person in El Arish was a wonderful man from Greece named Mr. Nick, the bar tender. He was a father, a resident psychologist, a man of great wisdom and was always willing to help those feeling down and out. This amazing man knew where every bottle and product was behind the bar and he was blind. He knew everybody by the sound of their footsteps and when you approached the bar, he would have your favourite drink waiting for you on arrival. One question you never asked Mr. Nick more than three times was “What’s for dinner Mr. Nick?” because you would get the same answer every time—“Eggs and chips!”

The bar tender and resident psychologist at the El Arish officers’ mess was an amiable and blind Greek by the name of Mr. Nick who found his way around his bar through feel and sound. Photo: Author’s Collection

The officer’s mess bar at El Arish was a stylish place in 1963. Pilot Officer George Mayer (right) with friend Bjorn, a Norwegian Army radio officer with UNEF. Photo: Author’s Collection

The Caribou ferry flight to El Arish from RCAF Station Trenton was worthy of a send-off party at Air Transport Command and some formal photos, Trenton. Here Flying Officer George Mayer (standing second from left) poses with Flight Lieutenant D. Scott (fourth from left), bound for his tour of duty at El Arish, along with well-wishing members of RCAF Air Transport Command staff. Photo: Author’s Collection

During our descent into El Arish from 9,000 feet over the Mediterranean, it got hotter and hotter and hotter and Scott had removed just about all of his uniform and was down to his Jockey shorts! I reminded him this was no way to greet his new Commanding Officer and, by the way, it is going to get hotter. After landing, we opened the rear cargo door and the blast of hot air was like a blowtorch, certainly not foreign to me! I waited a week for clearance to return the C-47 to Marville, and after the week boarded the mighty Yukon in France, bound for Trenton. Little did I know what fate had in store for me four months later in August—yes, another move. This time to Ottawa and 412 VIP Transport Squadron.

Three years later, in April of 1967, the news came over the Trenton jungle telegraph that a Lockheed CC-130 Hercules had crashed on the Trenton airport due to elevator trim failure on takeoff during a night training flight and the crew were all killed. It was the following day when I flew a 412 Squadron Dakota into Trenton over the crash site on the scheduled passenger flight from Ottawa. After flight planning back to Ottawa, I made inquiries about who was on board that flight. The news that my friend Jack Buchner was the captain hit me like a cannon shell. I briefed the co-pilot that he would fly the return trip and I would act as co-pilot as I was in no shape to fly as pilot in command. I knew Jack’s wife Jean, his kids and I mourn his passing to this day.

In summary, I dedicate this story to Flight Lieutenant Jack Buchner, Wing Commander Earle Harper, Flying Officer Paul Picard, and the Crew of Buffalo 461 shot down 9 August 1974 by a Syrian missile near but not over the Syrian border with a loss of 9 Canadian Peacekeepers. [For more on the story of the Buffalo 9, click here.]

I remain in the Service of Peace,

RCAF Flight Lieutenant (Ret’d) George E. Mayer, CD and Bar—UNEF, UNYOM

The UN flag in the Mediterranean Sea breeze at El Arish in 1963.