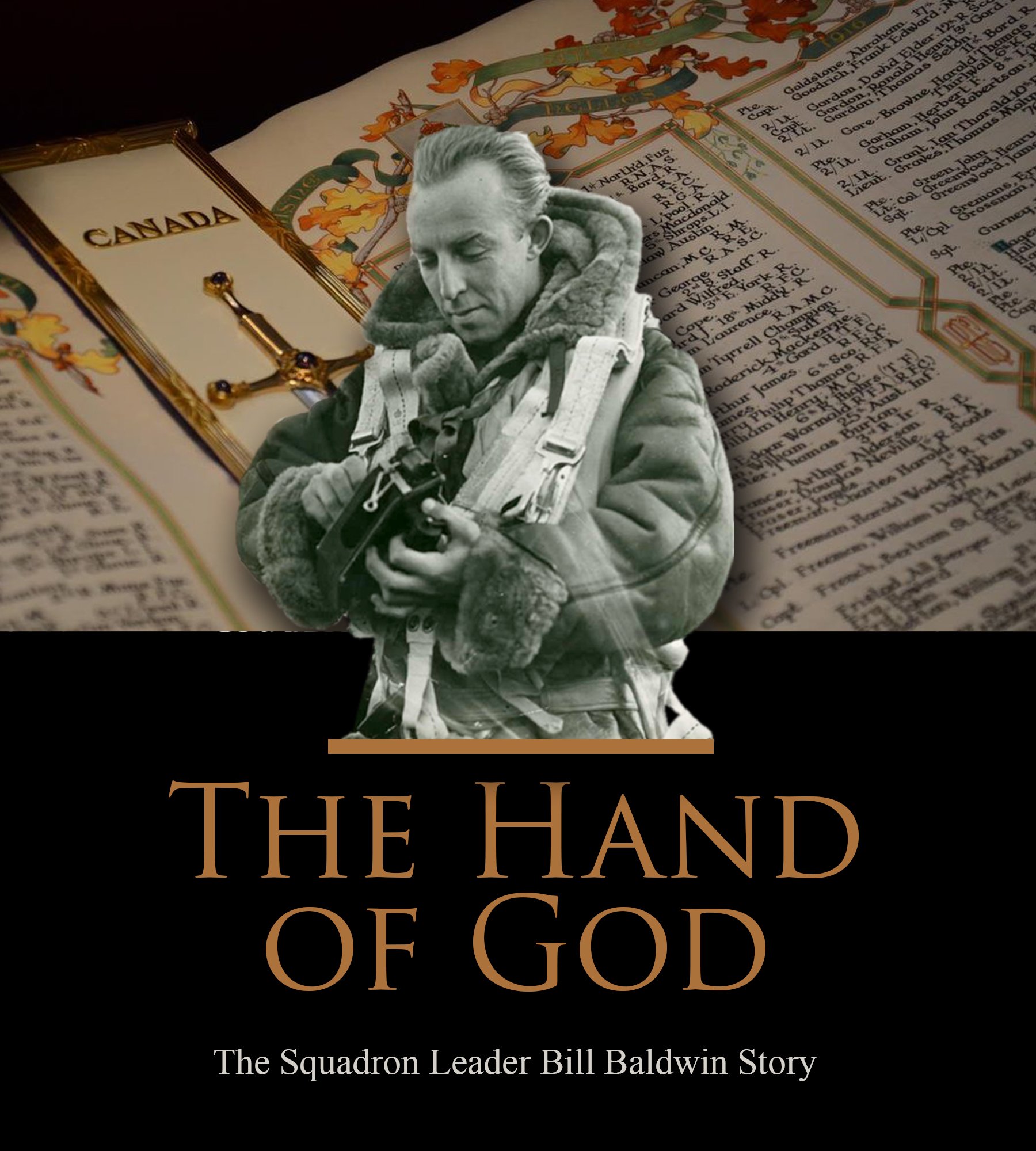

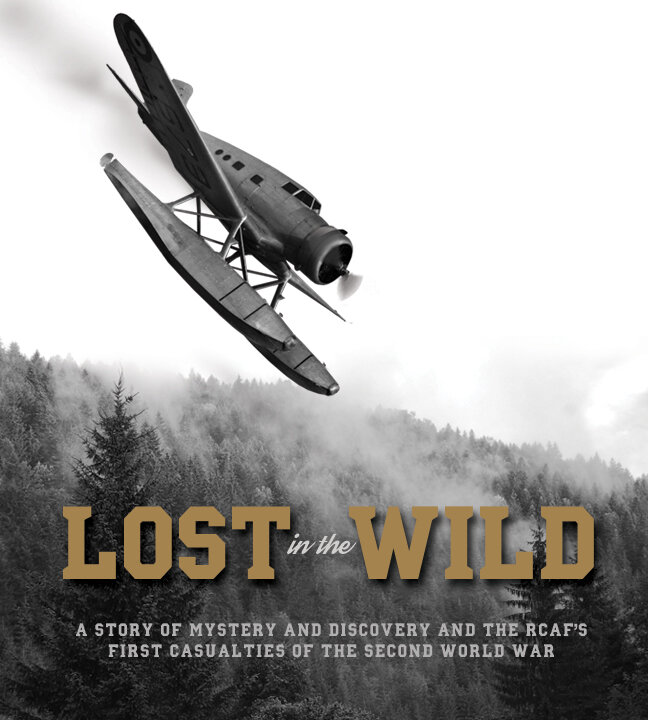

THE FIRST

Photo Illustration: Dave O’Malley

On Sunday, the third of September, 1939, the grain and sheep farmers of Aberdeenshire, Scotland having spent the early morning at church, went about their timeless work under a lowering grey sky. The harvest was in and the winter wheat still had to be sowed. Men were bent to stooking the wheat and barley by hand, while pairs of Clydesdales heaved against the dead iron weight of ancient mechanical reaper-binders. Across the land, the wind off the North Sea carried the rattle of harness and the bleating of sheep mingled with the popping and wheezing of one-lunger threshers, the rythmic coughing of clapped-out tractors and the whistles and calls of rubber-booted Aberdonian men to their collies — “Come by, Finn!” and “Away to me, Bess!”

For all its routine and enduring order, the day woud forever stand apart from all the rest. At 11:15 am, while the men took their tea and lunch in their cottages, they heard over the radio the tired, defeated voice of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain:

I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10, Downing Street. This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final Note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 0'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland a state of war would exist between us… …Now may God bless you all and may He defend the right. For it is evil things that we shall be fighting against, brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution. And against them I am certain that the right will prevail.”

Minutes afterward, in London, air raid sirens being tested wound up their ghostly wails and people across the city panicked, but in Aberdeenshire, the farmers and villagers imagined that war was still a long way away in both time and distance. They soon returned to their labours across the vale of the Don River where ancient water from the Grampian Hills found its way to the North Sea. To the west of the market town of Inverurie, known locally as the “Heart of Garioch”, the great mass of the Bennachie (Ben-e-hee) hills rose from the rolling farmland and disappeared into the low cloud. Bleak and rocky, the craggy massif shoulders out of the rolling land and pine forests around its base and consists of nine peaks above 1,300 feet covered in dense heather and strewn with boulders. At the centre, stands Oxen Craig, the highest at 1,735 feet and to the east, Mither Tap (Mother Top) at 1,700. Between these two, rises Bruntwood Tap at 1,535 feet — not very high relative to other mountains in Scotland, but just as immovable and homicidal. The farmland to its south sits at an average of only 275 to 325 feet above the level of the North Sea.

Around three o’clock that afternoon, the sky was grey and pressing down onto the crofts and pastures of Aberdeenshire, but it was comfortable weather for the heavy work at hand and typical of this time of year so close to the North Sea. Now there came a new sound heard by the men at their tasks, approaching from the southeast, the direction of Aberdeen on the coast. Even above the tractors and one-lunger machines, they heard it — the swelling drone of a big radial engine growing closer. With thoughts of war still racing in their hearts, they stopped and cocked an ear to the sound and an eye to the overcast. The aircraft, a large biplane silhouetted grey against the murk, passed in and out of the belly of the overcast. As it approached it seemed to disappear into the grey altogether, the pilot obviously staring straight down through the tendrils of cloud in order to pick his way northwest. Passing overhead, crofters looking up might have seen the ghostly silhouette of a Westland Wallace, a lumbering giant of a biplane, as it passed overhead, bleeding in and out of the haar.

“Passing overhead, crofters looking up might have seen the ghostly silhouette of a Westland Wallace, a lumbering giant of a biplane, as it passed overhead, bleeding in and out of the haar. ” Photo Illustration: Dave O’Malley

A rather elegant-looking Westland Wallace Mk I sits on a hard stand at RAF Martlesham Heath. The Westland Wallace was a British two-seat, general-purpose biplane of the Royal Air Force, developed by Westland as a follow-on to their successful Wapiti. Shortly after its introduction in 1933, a Westland Wallace became the first aircraft to fly over Everest, as part of the Houston-Mount Everest Flight Expedition. As the last of the interwar general purpose biplanes, it was used by a number of frontline and Auxiliary Air Force Squadrons. Although the pace of aeronautical development caused its rapid replacement in frontline service, its useful life was extended into the Second World War with many being converted into target tugs and wireless trainers. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A Westland Wallace made history in 1933 as the first aircraft to overfly Mount Everest. Six years later, it was long obsolete and the remaining examples of the type were relegated to towing targets for gunnery schools. Photo: rarehistoricalphotos.com

The North Sea littoral of Scotland was home to many legendary air bases that would play a vital role in the coming war — RAF Stations Banff, Lossiemouth, Peterhead, Dyce, Montrose, Dallachy, Kinloss, Alness and many others. Far from the glamour of the Brylcreem Boys on the fighter bases of the South of England, the regions of Grampian, Moray, and Easter Ross were to become home to the unheralded lairs of Coastal Command. Over the next five and a half years Coastal Command patrol bombers would range far and wide from here and Bristol Beaufighters and de Havilland Mosquitos would sally forth to torment German shipping in the North Sea and along the coast of Norway.

The Wallace had taken off from RAF Dyce to the north of Aberdeen just a few minutes earlier and was climbing to clear Bennachie, now obscured in the low cloud. The aircraft was on a ferry flight to RAF Evanton, on the north shore of Cromarty Firth. The Royal Air Force called the airfield Evanton, but it was also a Royal Navy aerodrome known as HMS Fieldfare. Evanton was home to No. 8 Air Observers School. A direct line from Dyce to Evanton would take the pilot and his passenger west of Inverurie and then straight over Bennachie, so the pilot must certainly have known the altitude of each of its rocky tops from his maps and the pre-flight briefing.

The drone of the climbing Wallace died out to the northwest as the men and women in the fields returned to their labours. If anyone had remained with an ear cocked to the last fading decibels of sound, they perhaps might have heard it stop abruptly and might have felt a distant tremor coming from up on cloud-shrouded Bennachie. It was the sound of the beginning of the war. The pilot of the Wallace had found the unforgiving granite slopes of the Bennachie Hills in the murk and had only a few seconds to think before they struck the bouldered flank of Bruntwood Tap.

The pilot in the front, 23-year old Pilot Officer Ellard Alexander Cummings, at that moment became the first Canadian and second Allied serviceman to die in the war, and an instant later, his observer, 24-year old Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Alexander Ronald Renfrew Stewart became the third. Both men were found by search parties still strapped in their cockpits. The tail of the Wallace had broken away from the main fuselage which suggested that it had hit first in Cummings’ last second efforts to pull the aircraft up. Both men had died instantly of broken necks and other traumatic injuries. The time of the crash was exactly ten minutes after 3 o’clock. That’s when Stewart’s watch had stopped.

The official cause of the crash was attributed to the poor visibility prevailing at the time, but one wonders if the altimeter in the Wallace was functioning properly or perhaps Cummings had either forgotten to adjust the altimeter for local conditions or mis-set the altimeter altogether. Why else would he press on over Bennachie in the haar while he was still below the known height of all of its peaks?

Bennachie’s Mither Tap from the heathered and scrub pine slopes of Bruntwood Tap. Photo: Shayne MacFaull via Google Maps

The farmland of Aberdeenshire as seen from the top of Bennachie’s Oxen Craig. Photo: Yvonne Vincent via Google Maps

The serial number, K6020 on this Westland Wallace MkII indicates it came of the Westland assembly line in Yeovil, Somerset just eight airframes ahead of the one flown by Ellard Cummings. The Mk II featured an enclosed cockpit for the crew, a first for an aircraft of the Royal Air Force. The use of canopies or enclosed cockpits was in use in commercial aircraft in Great Britain in the early 1930s, but the RAF had still to employ them. Photo: avionslegendaires.net

Ellard Cummings was the son of James Victor Cummings, an electrician, and Edith Fanny Ellard who lived at 46 Spadina Avenue in a west-Ottawa neighbourhood known as Hintonburg. James was superintendent of the transformer and meter department of the Ottawa Electric Company. Ellard was the oldest of his six children — Ellard, James, Donald, Kenneth, John and sister Myrle. Ellard likely attended Devonshire Public School which was just a few blocks from his home and then attended Glebe Collegiate Institute in the downtown neighbourhood known as the Glebe, a good half hour walk from Spadina Avenue. He had a love of sports and music and played a number of instruments including the violin, piano, mandolin, banjo and trombone. He owned a motorcycle and loved riding it or driving the family car to the family cottage along the Ottawa River.

After graduating from high school, Cummings found a job at the Beach Foundry in Hintonburg where they made cast-iron heaters, furnaces, ranges and ovens. In those days of the Great Depression a young man coming out of school considered himself lucky to get a job at a successful factory like the growing Beach Foundry but the adventurous Cummings could not see himself working an entire life in the dirty, dangerous and exhausting foundry, even if it was in the head office. Not long after he started work at the foundry, he contacted the Royal Air Force and was selected along with other Canadians to join the Royal Air Force.

When Ellard Cummings finished high school, he took employment the Beach Foundry in his Hintonburg neighbourhood. Beach products were a common sight in Canadian homes when I was young. They shut down operations in the 1980s and some of the original factory structures still exist today. Photo: R. D. Barry, Flickr

A studio photo of Pilot Officer Ellard Alexander Cummings taken in Great Britain shortly after he earned his wings and commission in the Royal Air Force. At right, a delightful shot of a beaming and boyish Cummings snapping his best air force salute for his family back home in Ottawa shortly after signing up and before earning his pilot’s brevet. Photos via: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

In the mid-to-late 1930s, a few adventurous Canadians began to take passage to Great Britain in the hopes of joining the RAF. Little was done by authorities to assist them in Canada and each man took it upon themselves to get across the Atlantic, whether on a liner or some “cattle boat” as was the term in the day. Not everyone was successful, as the RAF recruiters applied high standards and not a little condescension towards “colonials”. Canadian aviation historian Hugh Halliday, in a 2019 article in Skies magazine wrote:

“on March 26, 1935, the London Gazette announced that 68 young men had been “granted short service commissions [in the RAF] as provisional pilot officers on probation” with effect from that day. Six Canadians were among the number… …Besides these men, nine other Canadians would secure short-service commissions that year. In 1936 the figure was 70; in 1937 it was 116, and 127 in 1938.”

It seems Cummings was taking a risk, but thoughts of a lifetime in a foundry just a few blocks from his home drove him to find a life more adventurous. Halliday goes on to say:

“Enlistment was not always swift or happy. … … authorities in Canada attempted some medical checks and interviews, but there was no guarantee that an applicant, arriving by cattle boat, would necessarily be accepted swiftly. Complaints were made that some men, with no friends or family to help them, ended up living hand-to-mouth, even pawning their clothes. The RCAF liaison officer in London, S/L V. F. Heakes, described the situation as “pitiful” and ascribed it to incomplete information or downright misinformation provided in Canada.”

Canadians in the Royal Air Force at the outset of the Second World War were referred to as CAN/RAF airmen. Among them were some of Canada’s early heroes of the Second World War who were “on site” when the war started — men like Ottawa’s Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie, a Battle of Britain ace and last man out of the tunnel in the Great Escape, and Battle of Britain fighter pilots Willie McKnight, Howard “Cowboy” Blatchford and Mark “Hilly” Brown.

Though many Canadians went overseas on a whim and a prayer and might have ended up in a “pitiful situation”, it seems Ellard was not one of them. A short report in the society pages of the Evening Ottawa Citizen on March 29, 1938, Ellard was reported as “sailed from Halifax for Perth, Scotland and will train in the Royal Air Force for the next four years.” The specific mention of Perth and the four year term indicates Ellard already had a confirmed plan to enlist in the Royal Air Force.

Along with other recruits, he took passage on the Cunard liner RMS Andania, visting Plymouth on its way to Tilbury Terminal on the Thames outside London. There was a small group of Royal Air Force recruits who accompanied him on his voyage — Hugh Tamblyn, Selby Henderson, James Devereaux, Ken Heinbuch, Edmund Leveille, Thomas MacKenzie, and Douglas Matthew. Nearly all of them remained on the ship until it docked in London but some, like Ellard Cummings went on to Perth, Scotland by train to the RAF Depot there. Others on board claimed their final destination as Brooklands Aviation at RAF Sywell, Northampton or Airwork in Perth, Scotland which was the home of No. 11 RAF Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School (ERFTS). Some of these men like Selby Henderson had previous flying experience. Four of them — Cummings, Henderson, Leveille and Tamblyn would be killed on operations within a year and a half of Ellard Cummings; Leveille and Tamblyn on Hurricanes and Henderson in the Lockheed Hudson.

In March of 1938, Ellard Cummings took passage to Scotland on RMS Andania of the Cunard Line, arriving in early April. He was accompanied by other Canadian recruits of the RAF. Photo via tynebuiltships.co.uk

Sailing with him from Halifax to Great Britain aboard RMS Andania were three men who would also be killed in the next two years. Upper left: Pilot Officer Selby Roger Henderson, DFC of Winnipeg was killed on operations with 203 Squadron in July of 1940. Upper Centre: Flying Officer Edmond Kidder Leveille, also of Winnipeg was a Gladiator fighter pilot with 33 Squadron in Egypt. He was killed in late October, 1940 shortly after the squadron re-equipped with Hawker Hurricanes. Top right: Flight Lieutenant Hugh Norman Tamblyn, DFC of North Battleford, Saskatchewan and a Battle of Britain ace was killed with 242 (Canadian) Squadron in April, 1941. Bottom: One of the most published photographs of the Battle of Britain is this photo of fighter pilots of 242 Squadron taken at Duxford in 1940 at the height of the Battle of Britain posing with their commander Squadron Leader Douglas Bader. Hugh Tamblyn is second from the left. Bottom Photo: Imperial War Museum.

A few weeks later, on May 7, 1938, he was commissioned in RAF as a probationary Pilot Officer. According the website of The Bailies of Bennachie, a group dedicated to the natural environment, history and culture of those Aberdonian hills, Cummings ended up at RAF Sywell in Northampton, England. Here, he would have started his elementary flying training on civil-registered de Havilland Tiger Moths with No 6 Elementary and Reserve Flying School operated by Brooklands Aviation.

After his transatlantic crossing and some basic training, Cummings was granted a probationary Pilot Officer’s commission and posted to RAF Sywell (above) to begin flying training. Approximately 2,500 wartime RAF, Commonwealth and Allied pilots were trained at Sywell; the Aerodrome was also the centre for training the "Free French" pilots who had escaped to England from occupied France. Photo via FinestHourWarbirds.co.uk

Not much is known about Ellard Cummings’ career after Sywell until the accident that killed him except that on April 4th of 1939, he was granted his full commission (Date appears in London Gazette), which means that he likely had earned just his pilot’s brevet. If his service record with the Royal Air Force was available, we could determine more, but it’s safe to say that his career followed a familiar path of elementary and service flying training and then off to some sort of operational training and flying.

It appears that Cummings was posted to No. 1 Air Observer School as a staff pilot flying the Westland Wallace as a target tug for gunnery training for student observers. Between the wars, an Observer learned aerial gunnery as well as navigation and radio operation. By the time Cummings was flying the Wallace, the aircraft type was out of front line service and those that remained were equipped to tow drogue targets for aerial gunnery exercises. The rear cockpit of a Wallace aircraft was originally designed to accommodate an aerial gunner for defence, but in the case of a target tug Wallace, the rear cockpit was occupied by the winch operator for the trailed drogue. It’s not clear whether LAC Ronald Stewart was a winchman with No. 1 AOS or just a passenger hitching a ride.

Nearly every reference I have seen in the internet about the last flight of Wallace K6028 states that the Wallace was on ferry light from RAF Wigtown via Dyce, but that is impossible since RAF Wigton (also called Wigtown) was not opened until 1941. It was indeed the future home of No. 1 Air Observers School, but just not at the time of the crash. As with many errors in research, the mistake had permeated the telling of the story and taken on the stature of fact. At the time of the Accident, No. 1 AOS was housed at RAF North Coates on the North Sea coast of Lincolnshire. According to the Bomber County Aviation Resource, the source “For all things aviation in Lincolnshire”, within days of the declaration of war, “most of the based units at North Coates were transferred to the west of the country”. This was done to remove the training units out of harm’s way. This fact aligns well with the ferry flight movement of Cummings’ Wallace, perhaps to fly it out of harm’s way or simply to hand it over to No. 8 Air Observers School at Evanton.

The bodies of Cummings and Stewart were removed from the wreckage of Wallace K6028 and carried down the mountain — no easy task given the deep tangled heather, boulders and uneven, sloping terrain. They were taken to Inverurie and then on to Aberdeen where services were held. Ronald Stewart’s remains went by train to Glasgow and then Paisley where he was buried with his family in attendance. Ellard Cummings, being a Canadian was not returned home and was buried in Aberdeen’s Grove Cemetery just south of the Dyce aerodrome.

According to an interview with Kenneth Cummings, the son of Ellard’s youngest brother John, in the Calgary Herald in 2012, the family first heard of Ellard’s death on the radio. Shortly thereafter, with the family still reeling from and confused by the news, they received the first “REGRET TO INFORM YOU” telegram that 42,000 other Canadian families would receive over the next five years. It was a first for Canada, but it was not the last for the Cummings family.

A short piece about Ellard’s tragic accident ran on the front page of the Ottawa Evening Citizen on September 5th and after the family supplied a photograph of their son, it appeared on the front page again the next day (below). Within a couple of years, the death of yet another airman, sailor or soldier in the war against the Axis rarely made the front page.

Not long after Stewart’s burial in Paisley, his father Alan Stewart visited the site of the crash on Bennachie. It was reported that he retrieved part of the wooden propeller from which he carved a miniature model of a Westland Wallace for his and Cummings’ family.

The front page of the Ottawa Evening Citizen just three days after his death carried frightening headlines about Poland’s situation, reports of Ottawa passengers aboard the sunken passenger liner S. S. Athenia, the first ship sunk by German U-boats in the this war and Ellard Cummings (centre), then thought to be the first casualty of the Second World War. Image via Newspapers.com

The miniature model of a Westland Wallace carved by Stewart’s father from a piece of the wooden propeller from the crash site. A very poignant reminder and a special gift which Alan Stewart sent to the Cummings family. Photo: Unknown at this point. Possibly Linzee Druce

I found very little about Pilot Officer Cummings on the internet and lot less about LAC Alex Stewart. He was the son of Alan Stewart and Elizabeth Renfrew of Paisley, Renfrewshire on the western outskirts of Glasgow. He had two brothers and two sisters and was engaged to be married. Photo: Ancestry.com

The man given the unfortunate title of the first Allied serviceman to die in the war was probationary Pilot Officer John Noel Laughton Isaac who lost control of his Bristol Blenheim on only his second solo flight on the type. He crashed into a residential area near Hendon and was killed, 90 minutes after war was declared. Photo: Roath Local History Society

To die in war is a tragedy of immense proportions. Each young life is a story of potential squandered, of beauty consumed by violence, of unimaginable grief for mothers, fathers and spouses. To have died in that horrific war is tragic and a sacrifice that for many millions of people in Europe and the Far East is, today, largely forgotten on an individual basis. For a country with a small population like Canada’s during the Second World War, the numbers were tiny fractions of the loss felt by countries like Russia, Poland, Japan, Germany and nations in Europe and the Far East, but none the less, the pain for our country is felt to this day. All these deaths are tragedies, but to be the first or the last of these numbers carries a certain extra tragic significance. To be first, to be taken out of the fight in the opening gambit, to die without testing one’s mettle is akin to the first pawn taken in a chess game... gone, forgotten and out of the game.

The second Canadian airman to die in the war was Sergeant Albert Stanley Prince of Montreal who was killed on September 4 while attacking cruisers of the Kriegsmarine in Wilhelmshaven, the German Navy’s main base on the Baltic. The third was 22-year old Flying Officer Earl Douglas Godfrey of Saskatoon. He was also killed on September 4th in a 233 Squadron Lockheed Hudson which stalled on take-off from RAF Leuchars and crashed inverted into the River Eden. The fifth, Pilot Officer Anthony Richard Playfair of British Columbia, aged 25, was killed on the fifth in Doncaster, South Yorkshire. He lost control of his Handley Page Hampden on a training flight while practising single engine flying. On that same day, Pilot Officer James Healy Cavanagh was killed near Bristol, England while in flight training. His death however was in an automobile accident under blackout conditions.

Brothers-in-arms

Though Ellard Cummings looked so young and beaming in the photos he sent back to his family from Great Britain, he was in fact the oldest child of James and Edith. There were four younger brothers and a sister who looked up to him and who were likely thrilled to tell their classmates and buddies that their older brother was a pilot in the Royal Air Force. His brother Clayton was three years younger than him, John four, Donald five and Ken seven years younger. The baby of the family, Myrle was born eight years after Ellard.

When their idol Ellard was killed on the opening day of the war, there is no doubt that all of them were devastated by his loss. His death accompanied the announcement of the war in Europe and like all young people in Canada, they wanted to enlist. Three of Ellard’s brothers would enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force when they came of age, no doubt inspired by Ellard’s sacrifice. When Ellard was killed, the youngest of them, Ken, was just 15-years old and attending Glebe Collegiate Institute as did all the children.

When he graduated with a junior matriculation in 1941, Ken followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming an electrician and working for Ottawa Light, Heat and Power Company as an Assistant Power House Operator. Like his older brother, he didn’t last long. Wanting to join the fight against the Germans, and perhaps to honour Ellard, he enlisted in the RCAF, took the oath to His Majesty King George VI and signed his attestation papers on November 21, 1941.

He was immediately handed a travel voucher for Brandon, Manitoba where he was posted to No. 2 Manning Depot. Most recruits were sent to manning depots close to their homes and Ken would have had several depots much closer than Brandon — Toronto and Picton in Ontario and Lachine and Quebec City in Quebec, but he travelled to Manitoba to begin his training. After Manning Depot, he was shunted around various western bases for “tarmac duty”, guarding something in no need of guarding to keep him busy until space in the training system opened up. Twice (while at Manning Depot and during his Initial Training phase in Regina) he was hospitalized for a week.

Young Cummings was no standout pilot trainee, nor was he assessed as anything but a good average pilot. He graduated from his Initial Training School in Regina 75th out of 123 students but was assessed as “hard-working, quiet and determined. He should prove to be very good pilot material. He is keen to fly and get overseas.” He came in 25th in his class of 43 at No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School in Lethbridge, Alberta but was rated “High average all around student, keen and alert, officer material, conduct very good”. In his last stage of pilot training he came 35th out of 50 students at No. 7 Service Flying Training School in Fort MacLeod [where Joni Mitchell’s father was an instructor-Ed]. Here his assessment was much weaker: “Just average as a Pilot, and Ground School. Inclined to be careless in his attitude towards flying duties, as well as his studies. Requires constant checking. Not recommended for a commission.“ Regardless of the poor assessment, he made the grade and earned his pilot’s brevet in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was the second of his family to wear those coveted wings and no doubt he was mighty proud. His family, on the other hand, may have been understandably nervous.

Two photos of Ken Cummings. The left likely was shot in Ottawa when he was still at school and the right at Manning Depot in Brandon. Photos via: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

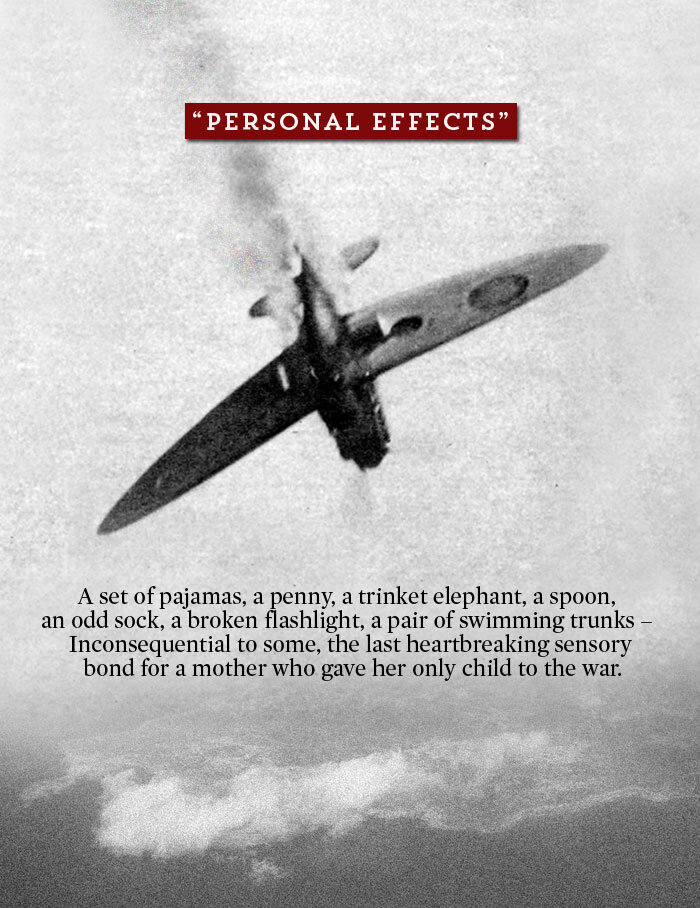

A photo of LAC Ken Cummings in front of an Avro Anson at No. 7 Service Flying Training School in Fort MacLeod, Alberta, likely in September of 1942. It was at No. 7 SFTS that Cummings earned his pilots’ brevet and followed in his brother’s footsteps. Interestingly, he is wearing a sweater vest, a fashion accessory he seemed to like. When his personal effects were returned to his family after his death over Germany, they included no less than 13 vests! Photo via: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Flight Sergeant was then granted Embarkation Leave in Ottawa before finding his way to Halifax, Nova Scotia. On the 10th of December 1942 he boarded a troopship in Halifax, bound for Great Britain and arrived there eight days later. His next posting was at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre at Bournemouth, Dorset, there to await assignment and posting. Shortly thereafter, he was posted to No. 15 (P) Advanced Flying Unit (AFU) at RAF Leconfield to adjust to flying conditions in the UK. An Australian website called Birtwistle Wiki has an excellent explanation of the use of an Advanced Flying Unit:

“Numbered (P) AFUs existed in the RAF from about February 1942 onwards to "acclimatise" newly arrived pilots from the British Dominions "over the seas" to flying conditions in the UK, and this continued to the end of WW2. All these aircrew were technically fully qualified and badged, so were strictly speaking not trainees as such, and were actually receiving "advanced" (post-graduate) training. These units were only introduced because so many pilots found the flying conditions in wartime UK airspace were completely different to the safer and generally clearer skies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. What with so much more cloud, winter fogs, industrial smog, thousands of small villages and hundreds of cities, railway lines and roads everywhere, and barrage balloons and anti-aircraft guns all over the place, as well as thousands of aircraft and hundreds of airfields scattered about every flat bit of ground, the newly arrived aircrew from overseas found the UK flying conditions very foreign and stressful, and accidents were becoming too high. Thus the AFU's came into being to improve their chances of survival before they even reached the OTUs.”

From Leconfield, he took a brief course at No. 1513 Beam Approach Training school at RAF Bitteswell in Leicestershire and eventually on to 1652 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at RAF Marston Moor, being taken on strength there on August 10th, 1943. At the HCU he would make the transition from twin-engine aircraft which he had flown so far in his training to the complexities of four-engine Handley Page Halifax bombers and crew management. It would be here at Marston Moor where he would meet up with other pilots as well as navigators, engineers, bomb aimers, radio operators and gunners and from this course gather together a crew of six others and take on the tile and responsibility of a “Captain”. This would be the first great achievement of any bomber pilot’s wartime career. He now had responsibility for six other men as well as his mission. His word was final within the confines of a Halifax and it would be his ability to make good decisions that each of his new crew hoped for. For a 20-year old from Ottawa, it was a fearsome responsibility.

On the 5th of October, 1943, Flight Sergeant Kenneth George Cummings and his crew were posted to 102 Squadron, Royal Air Force, a Halifax-equipped squadron of Bomber Command based at RAF Pocklington. While the crew settled in and were evaluated by 102 flight commanders, Cummings went on his first “op” on the 8th of October. This would be his “Second Dicky” flight, an op in which he flew as the second pilot with a more experienced crew to get the feel of a real night bomber raid. That night, with the weather conditions clear and the target well marked by pathfinders, 504 RAF aircraft (Lancasters, Halifaxes, Wellingtons and Mosquitos) attacked Hanover. German night fighters shot down 27 aircraft and just like that Bomber Command was now down 127 well-trained men. Cummings’ crew would now be used to help replace the losses.

A Handley Page Halifax II of 102 Squadron flies over Yorkshire in 1944 while filming a sequence for an aircraft recognition film. The full film from the Imperial war Museum can be seen here.

Now blooded, Cummings was ready to take his crew on their first op. That crew as comprised of Flying Officer Owen P. McInerney, RCAF, Navigator; Sergeant Leslie G. K. Giddings, RAF, Flight Engineer; Sergeant Norman F. Lingley, RAF, Wireless Operator; Sergeant Robert. P. Rees RAF, Mid-Upper Gunner; Sergeant John Torrance, RAF, Rear Gunner; Sergeant George C. Clarke, RAF Bomb Aimer. Their Halifax (JB844 “S” for Sugar) was one of nineteen 102 Squadron Halifaxes participating in a raid on the central German city of Kassel. Cummings was airborne at 1748 hrs. 102 Squadron’s Halifaxes merged with the bomber stream of 550 other aircraft whose mission was the complete destruction of Kassel’s town centre. A total of 1,800 tons of bombs including a terrifying 460,000 magnesium incendiaries were dropped in a concentrated area. For Cummings and his men, it must have been an frightening and sobering sight to see this ancient city below them caught in the agony of a firestorm. Cummings brought his crew home safely, touching down at RAF Pocklington at half past midnight.

On November 3rd, Cummings and the crew were up again, this time on a raid to Dusseldorf with seventeen other 102 Squadron Halifaxes. According to the Operations Record Book for November, they were flying in JB844 again, but this time it was coded “L” for Lanky. They were off by 17:03 hrs and back down safely about five hours later after a bit of a milk run with “Little trouble experienced from flak, searchlights and fighters, though several crews reported narrow escapes from collision with our own aircraft, en-route and over the target.” The Cummings crew did not participate in any squadron operations for the rest of the month, likely because they were going through some additional training.

A 102 Squadron Halifax I waits at RAF Pocklington in the summer of 1943 while the Station Commander (centre) signals them to begin their take-off roll. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Exactly a month after their last raid, the Cummings crew was up again, this time on a raid to Leipzig, Germany. Up to this point in the war, Leipzig had escaped any major bombing raids, with only minor raids on outlying suburbs, but on the night of 3-4 December, that changed. The RAF arrived in force with 442 bombers dropping nearly 1,400 tons of high explosives and incendiaries. 102 Squadron supplied sixteen of their Halifaxes for the raid, with Cummings and crew taking their JB844 (now coded “U” for Uncle) off Pocklington’s runway second last at 11 minutes after midnight. They didn’t get far. Having crossed the Zuiderzee into Holland en route, they experienced trouble with No 3, the starboard inner Bristol Hercules engine. Forced to return, they jettisoned their bombs over the North Sea and landed back home shortly after 2 a.m.

Again, the Cummings crew had a long respite for training and were not on another raid until the 22nd, an attack on Frankfurt, one of the most bombed cities in Germany with more than 75 raids over the course of the war. There were twenty-one Halifaxes of 102 Squadron involved, a real maximum effort for the squadron. The Cummings crew were assigned a new bomber, HX187, “H” for Harry. Their old ship, the war weary JB844, was reassigned to 1658 Heavy Conversion Unit where it did journeyman service until July, 1944 when it burned up after a forced landing. They had only two raids in all of December, but by now the Cummings crew had four ops under their belt and their Captain five.

In January, Cummings flew even less, participating in only one raid, this time on Magdeburg on the Elbe Rover, the original seat of the Holy Roman Empire and now laid waste by previous raids. On this night Cummings and fourteen other 102 Squadron captains brought their crews into the bomber stream of 648 aircraft (421 Lancasters, 224 Halifaxes and 3 Mosquitos) but even before they entered Germany the Tame Boar* night fighters were in the stream and playing bloody havoc. It was a cock-up right from the start with some of the stream arriving before the Pathfinders and bombing inaccurately. The fires they started were taken for the Pathfinder markers with following bombers dropping on those flames. The Pathfinders blamed the fires started by this early bombing, together with some very effective German decoy markers, for their failure to concentrate the marking. Having taken off at just after 8:00 pm on the 21st, Cummings and his exhausted crew touched down safely at 3:15 am on the 22nd. Thirty-five Halifaxes and and 22 Lancasters were brought down that night with an estimated 3/4 of them by Luftwaffe fighters. Again, 400 men were lost in just a few hours. Bomber Command could never sustain these losses regardless of what the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan could supply them. Of those 400 men, 28 were from 102 Squadron. Those four aircraft, combined with five losses an a raid to Berlin the night before meant that 102 Squadron had lost more than a third of its strength in less than 30 hours.

At the end of January, the squadron commander filled in a confidential personal assessment form for Cummings and he came off as a solid if average bomber captain. In the category of Energy and Persistence he was deemed “Vigourous , enthusiastic in all he undertakes”, In Mental Alertness he was rated “Exceptionally quick to understand what is required”. In the category of Power of Expression, the assessor, Squadron Leader J. Pearce ticked the box for “States what he means clearly”. And on it went: For Initiative he was rated “Displays initiative when the course is clear.“ Under Accuracy and Reliability it was “Can depend on him for the performance of all ordinary duties”. He was also assessed to be one who “promotes harmony and good will among his crew and associates”. Though he was deemed average in this assessment, it must be stressed that becoming an average heavy bomber pilot was an exceptional accomplishment in every respect. Average was a solid endorsement of his skills.

On January 28, the Cummings crew and 16 others took off for the greatest target of them all — Berlin. They were up in Halifax LN329, “O” for Orange, at 6 minutes after midnight on the 29th and didn’t get home until after 8:00 am that morning. It was exhausting work.

At the beginning of February, his fifth month on squadron, his crew had just six ops in the books and one of them was cut short for engine trouble. Most of the other crews on squadron had 10 to 13 ops completed in that same period. Perhaps new crews, going through additional training after arrival on squadron, picked up the pace after a certain period. The Cummings crew’s first op of February was on the night of February 11-12 — a “gardening” mission to drop sea mines from 12,000 feet in enemy shipping lanes or on a harbour somewhere—the location was not noted in the squadron diary or ORB.

On the night of February 15-16, Cummings participated in another raid on Berlin. Of the 20 Halifaxes of 102 Squadron involved, six returned with technical issues and two were shot down. Berlin had a way of convincing many crews that their technical problems were insurmountable. Cummings was off shortly after 5:00 pm and landed back just after midnight.

“We Regret to Inform You” … all over again.

The pace was beginning to pick up for the Cummings crew through February and they began to match raid for raid with the other crews. On the 19th, they were back in action, this time to Leipzig again with 18 other 102 Squadron crews. Cummings with his complete original crew of McInerney, Lingley, Rees, Torrance, Giddings and Clarke took off ten minutes before midnight, climbing into a dark sky lit only by the blue exhaust flames of 102 Squadron Halifaxes. It was cloudy and snowing sporadically, but the visibility was generally good with light winds out of the north-northeast. There were 823 aircraft in the bomber stream this night.

Crews reported heavy engagement from night fighters along the route. It was a running fight to and from the target. Five 102 Squadron aircraft returned to base early with various technical problems that prevented them from reaching the target and releasing their bombs— fuel flow, engine and radio problems and one because it was damaged by flak that had also their injured radio operator. Tail winds were stronger than had been predicted and many bombers arrived early and had to orbit the target awaiting the Pathfinders, further increasing the likelihood of being picked off, either by flak or fighters. In the end, 78 of the bombers were shot down this night, accounting for nearly 550 men. When the last Halifax chirped down on the Pocklington runway at 7:30 am that morning, two of the squadron aircraft were not among them— “B” for Beer, Flying Officer W. Dean commanding and Ken Cummings’ “H” for Harry (JN927).

Back at Pocklington a few hours later, the last returning Halifax, “W” for William, touched down with the dawn just beginning to provide light enough to find their way to the hardstand where they shut down. Farther along the dispersal, two groups of RAF ground crew waited in vain for Harry and Beer. After 8:30, with the sun just clearing the horizon the realization was sinking in. Cummings had not made it.

Cummings’ aircraft was shot down and had crashed into a moor in the vicinity of Sulingen, Germany, about 40 kilometres south of Bremen. Of the crew of “H” for Harry, only two survived. What had happened wasn’t known until Owen McInerney was interviewed following his release from a Prisoner of War camp in May of 1945. In addition to McInerney, the navigator, Les Giddings, the wireless operator survived both the crash and POW camp. The main escape hatch for the Halifax forward compartments was on the floor below the Navigator’s seat, so it makes sense McInerney would be out quickly. The Wireless Operator was the next closest. The Pilot was above this level and needed to squeeze down a couple of steps to access the hatch. The Engineer’s closest escape was aft through the crew door. Luckily for me as a researcher, McInerney was a Canadian so his post war account of the event was in Cummings’ service file. Had he been a member of the RAF, I could not easily access those files held at the National Archives of Great Britain.

McInenery reported that the aircraft, hit by a night fighter or possibly flak, was spinning out of control and that Cummings had ordered the aircraft abandoned. He saw the Wireless Operator Lingley drop through the escape hatch, then followed him. Just before he went he looked up and saw that the Bomb Aimer Clarke was ready to follow him from his position in the nose and he saw Cummings coming down the steps as the aircraft began to spin more violently. And that was the last anyone ever saw of Ken Cummings, brother of the first Canadian to die in the war. As aircraft captain he was the last to attempt to get out of his dying aircraft.

McInerney’s account was to the point and unadorned as it should be for a humble and straight forward airman making a report, but it belies the utter chaos of the moment. Unspoken are the terrors of the engines howling, the claustrophobic and nearly pitch-black compartment lit only by a small task light, the choking smell of cordite, aluminum, smoke and fear, the massive pull of centrifugal force as the giant Halifax spiralled in the black void, the vibration so extreme that focus is impossible, the flying grit and maps, the dry mouth, the fumbling for hatch and parachute harness, the shriek of the icy slipstream through the open hatch, the muffled shouts of men attempting to save their lives.

The next day, a captured McInerney was reunited with Giddings who told him that he saw both gunners Torrance and Reese ready to follow him out of the rear door when he leapt free. They were unable to get out of the spinning aircraft however and they died when the aircraft hit the ground. Though Lingley had made it out, he was also killed — perhaps his parachute failed to open.

Two days later, back in Ottawa, the telegraph boy turned his bicycle onto Spadina Avenue and rang the bell at number 46. We’ll never know who answered, but as soon as it was signed for, the messenger likely beat a hasty retreat. The news in these telegrams was not always bad, just most of the time. These difficult telegrams followed a very specific construct, a phrasing and pacing of words that was learned the hard way — after informing thousands upon thousands of next-of-kin over two world wars. The words left no false hope nor did they destroy hope. The specificity left no chance that they had the wrong person. The telegram in the hands of the worried recipient at the front door of 46 Spadina would have most certainly read:

REGRET TO INFORM YOU ADVICE HAS BEEN RECEIVED FROM

THE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE CASUALTIES OFFICER OVERSEAS THAT YOUR

SON PILOT OFFICER KENNETH GEORGE CUMMINGS CAN J ONE NINE EIGHT ZERO THREE

IS REPORTED MISSING AS THE RESULT OF AIR OPERATIONS ON FEBRUARY TWENTY

NINETEEN FORTY FOUR STOP LETTER FOLLOWSCHIEF OF AIR STAFF

Though crew list for “H” for Harry in the squadron ORB for the Leipzig raid identifies him as a Flight Sergeant, the telegram’s reference to Cummings’ service number J/19803 tells us that he was no longer a Flight Sergeant pilot (The “J” prefix was given to officers). He had been promoted to Pilot Officer a few of weeks earlier, made effective the very night he died. If he had made it home to Pocklington, he would have had a celebratory beer in the officer’s mess for the first time.

A telegram was initially used to get the news to the next-of-kin as quickly as possible. All following correspondence, was in the form of a signed letter. The telegram would have devastated the close Cummings family, just as the first one had. It would be James’ difficult task to call two of his remaining three sons who were serving in the armed forces to deliver the news. Sergeant Donald Cummings was serving at No 31 Air Navigation School in Port Albert, Ontario on the shores of Lake Huron and Lieutenant Clayton Cummings who was due to be married in a few weeks in Montreal was serving with the Canadian Dental Corps. Son John and daughter Myrle were still living at home.

In February of 1944, the Germans seemed far from defeat. D-Day was still five months in the future and the prospect of losing another son to the war most certainly weighed on James and Edith. Clayton was in the Canadian Dental Corps, stationed safely at Uplands in Ottawa and Myrle was still living at home having just finished high school. But Donald was a sergeant in the air force stationed at No.31 Air Navigation School in Port Albert, Ontario. Though he was not studying to be a navigator, there were plenty of ways to die on an active air base.

In the end, the Cummings family did not have to dig even deeper for the war effort. Their burden was heavy enough. The war ended, Donald came home and life continued, though it would never be the same. Their beloved son Ellard’s death became synonymous with the beginning of the war and young Kenneth’s role on the strategic bombing campaign over Germany got swept under a rug of moral rectitude.

After a long illness, Edith died in 1960 at the age of 72 having carried the burden of her first son’s death for nearly 20 years. James died in 1973. Myrle was married to Donald MacPherson in 1955. She died two years ago in April, 2021. Ellard’s brother Donald named his first-born son Kenneth Ellard Cummings, thus honouring his two lost brothers.

In 1949, a former RCAF 427 Squadron wireless operator visited the Hanover, Germany graveyard dedicated to Allied servicemen (mainly from Bomber Command) who were killed on operations in Germany. The remains of the men in this cemetery were brought here from all over Germany. He took a few photos of the grave marker of a Sergeant Roy Wells, one of his own crew and then sent copies of the photos to his navigator Flying Officer Adam Meyers of Toronto, who also survived the shooting down of their Halifax. Adam Meyers understood that the family of Ken Cummings whose grave marker was also captured in the photo would appreciate having a copy of the image so that they could see that their son was well taken care of and he sent the photo to the RCAF who passed it on to James Cummings. The remains of Clark, Lingley, Rees and Torrance are buried in a communal grave with separate headstones. Photo via Canadian Virtual War Memorial

The wreckage of Westland Wallace K6028 still lies strewn about the rocky slopes of Bennachie’s Bruntland Tap. The rusting Bristol Pegasus engine from the Bennachie Wallace remained on the hill until the 1960s, when a local firm recovered it with the intention of selling it for scrap. When the RAF learned of this plan they acquired it, intending to restore it for display. Photo: What To Do When Highland Dancing

A memorial was built at the top of Bennachie to honour Cummings, Stewart and a pilot named Brian Lightfoot who flew into the mountain in similar conditions in a Gloster Meteor jet fighter in 1952. The cairn is made of rock from the mountain with parts of both aircraft embedded on the mortar. Photo: What To Do When Highland Dancing

The granite plaque set in a stone cairn at the top fo Oxen Craig helps the thousands of hikers who summit Bennachie each year to understand what happened there so long ago, when the world fell into the abyss. Photo: What To Do When Highland Dancing

Story first published October 29, 2023

Other Stories From the Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa

Click on image

* Zahme Sau, generally known in English as "Tame Boar"was a night fighter interception tactic conceived by Viktor von Loßberg and introduced by the German Luftwaffe in 1943. As a raid approached, the fighters were scrambled and collected to orbit one of several radio beacons throughout Germany, ready to be directed en masse into the bomber stream by running commentaries from the Jagddivision. Once in the stream, fighters made radar contact with bombers, and attacked them for as long as they had fuel and ammunition. (Wikipedia)